I’ve had this sitting in my drafts folder for a while, and I decided I’m going to publish what I have and add to it as needed.

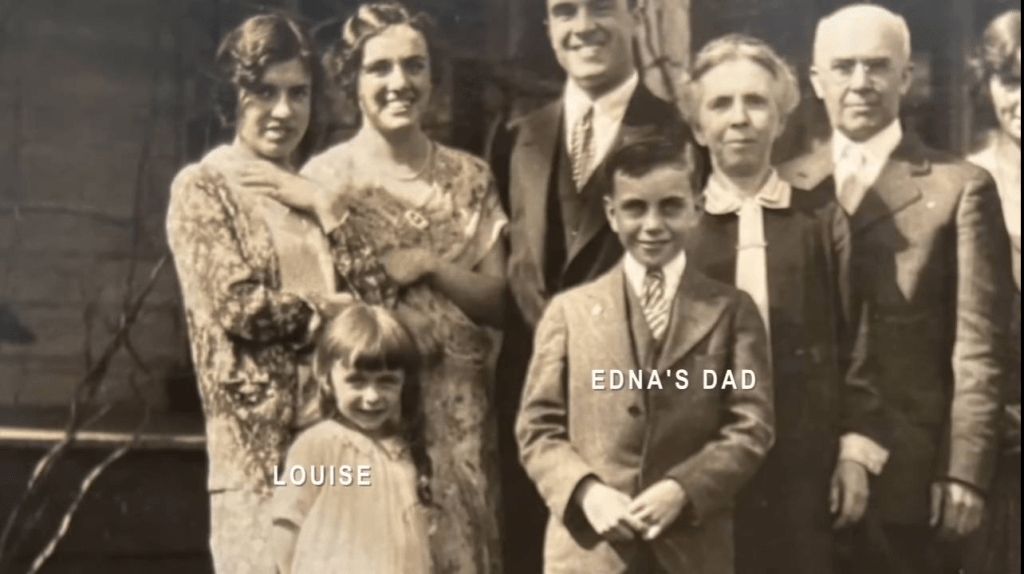

Sam Cowell is Ted’s Father: there’s a pretty commonly spread myth that Ted’s grandfather Samuel Cowell is his father... but a blood test performed in 2020 by psychiatrist Dorothy Otnow-Lewis determined this to be not true.

Ann Marie Burr: there’s a myth that Ted’s Uncle Jack was Ann’s piano teacher, he wasn’t (although he did live about three miles away)’; there’s also a rumor floating around that Ted was the Burr’s family paperboy, he wasn’t. He also lived over three miles away from her and not exactly in her neighborhood.

Karen Sparks: before she was brutally attacked on the night of January 4, 1974, Sparks recalled being watched by an older-looking man at the laundromat that she usually went to.

Lynda Ann Healy: on the day after she vanished Lynda had plans of making her family a home cooked meal called ‘company casserole;’ additionally, there’s also some evidence that Bundy stalked her before he abducted her in the early morning hours of February 1, 1974, as it was proven by the King County Sheriff’s Department that on the day she was last seen alive he was behind her in the check cashing line at the Safeway they both shopped at. Ted also frequented Dante’s, the bar Lynda went to on the evening that she was last seen alive.

Donna Gail Manson: there are some whispers that Ted was acquainted with Donna, and that she had been seen in the presence of a man that matched his description prior to her disappearance on her school’s campus.

Susan Rancourt: before Ted abducted Sue he approached two other women: Kathleen D’Olivio and Jane Curtis. He approached D’Olivio earlier in the evening on the April 17, 1974 (the same night Sue disappeared), however there’s some discrepancy as to when he approached Jane: in multiple sources it’s alluded that it occurred the same evening, however Curtis said she was approached on a Sunday (Sue was abducted on a Wednesday), so that means she encountered him either on April 14, 1974 or April 21,1974.

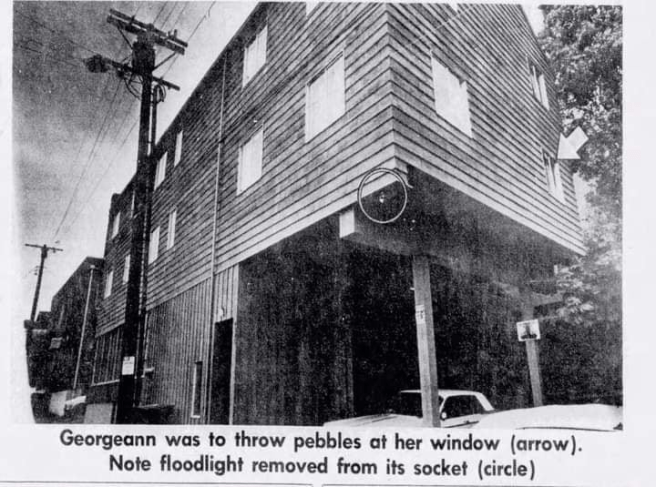

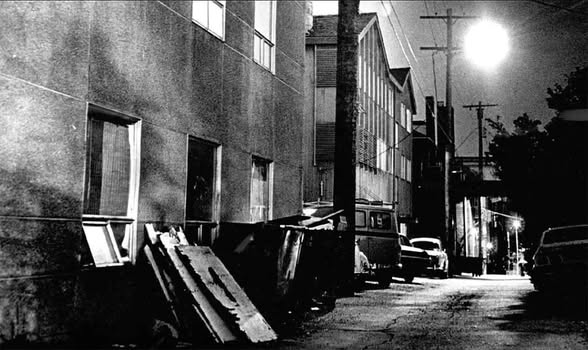

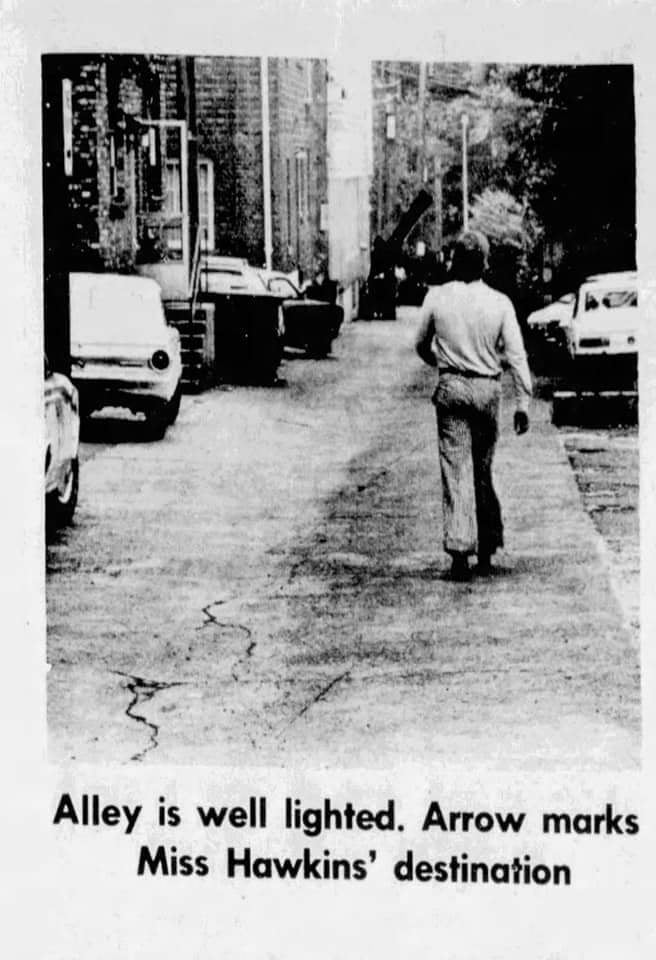

Georgann Hawkins: the day after Ted abducted Hawkins he returned to the area close to the crime scene and (very discretely) recovered a pair of her hoop earrings and one of her shoes from an adjoining parking lot (that had all flown off of her because he attached her with such incredible force).

Brenda Carol Ball: according to Bundy’s death row confessions, he admitted that he took twenty-two-year-old Ball back to his rooming house in Seattle after abducting her on June 1, 1974, and the two had consensual sex; he then claimed to he strangled her while she slept. This is inconsistent with the physical evidence, as her skull (which had been discovered in 1975 on Taylor Mountain), showed significant damage from blunt force trauma, proving that she had been severely beaten.

Lake Sammamish Murders: there’s multiple theories as to why he took two women in the same day. One is that because Jan Ott was so small he killed her ‘too quickly’ by accident, and his ‘urges’ weren’t completely satisfied so he had to go back and get another victim. The second theory is that he kept Janice alive and brought Denise back to where he was keeping her and killed the one in front of the other.

Nancy Wilcox: It’s speculated that Bundy may have been grooming Wilcox, as members of her family said she mentioned an older man who would come into the Arctic Circle drive-in that she briefly worked at and flirt with her.

Laura Ann Aime: there were apparently several reports made to police by people that knew Aime that said she claimed that a man matching Bundy’s description had hung out with her at Brown’s Café in Lehi, Utah, and at one point had called her his girlfriend. The man also had said he was going to rape her, and its thought she had been introduced to him by her friends. Additionally, Laura’s family has stated they believe Bundy stalked her and approached her on multiple occasions before he abducted her.

Pulled Over in Florida: before his final arrest in Florida in early 1978 Ted was pulled over in Tallahassee driving a stolen vehicle and as he was being questions by an officer. He simply, ran away… and he got away. This took place just four days before his final arrest on February 11, 1978: when the officer walked back to his patrol car to check the license plate, Bundy ran away and escaped into the night.

Valerie Ann Duke: a student at FSU at the time of Bundy’s Chi Omega murders, Duke had gone home the weekend of the murders and because of that her life was spared (Bundy’s fingerprints were found on her doorknob, meaning had she been there she would have been attacked); she lived with immense survivors guilt and shot herself in her vehicle on May 1, 1979, at the age of 22. She was born on July 27, 1956 and is buried at the Cenizo Hill Cemetery in Mathis, Texas.

Deborah Wharton Beeler: one of Ted’s Seattle attorney’s John Henry Browne dated a woman that was brutally murdered in the same fashion that Bundy killed his victims. Beeler had been found in her rented cottage on February 22, 1970 wearing a housecoat over a nightgown; the twenty-three-year-old had been strangled with an electric hotplate cord. Investigators initially believed she committed suicide because within reach were a pair of pliers that had apparently been used to righten the wire, however an autopsy showed she had been hit over the head and had crashing blows to the side and front of her head (injuries that may have been made by a fist).

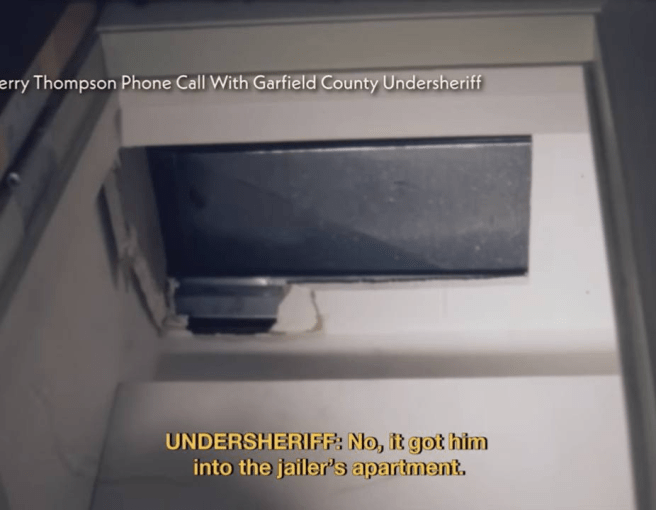

A Third Escape?: in July 1984 guards at Florida State Prison found a cut bar, hacksaw blades, and a pair of gloves hidden in Bundy’s cell. Another inmate, Manuel Valle, also had a cut bar in his cell, which suggested a coordinated effort between the two men.

Two Beetles?: Ted actually owned two Volkswagen Beetles, not just one (Liz owned a pigeons egg blue VW Bug as well). In April 1966 he sold his a 1933 Plymouth Coupe to put money towards a pale blue 1958 VW Bug. At some time in the spring of 1973 he purchased his infamous tan 1968 VW Bug from a woman named Martha Helms.

Susan Roller/Sara A. Survivor: a (living) supposed repeat victim of Ted named Susan Roller has published three books under the pseudonym ‘Sara A. Survivor;’ Roller also claims to be a friend of Georgann Hawkins as well, as the two were Daffodil Princesses (in different years)… however, I could find any proof that she knew either Bundy or Hawkins. In her book ‘Reconstructing Sara,’ Roller told her story about being repeatedly assaulted and raped by the SK; as of February 2026 is has been pulled from publication to be rewritten.

Zak Bagan’s, ‘Ghost Adventures’ Episode, ‘Serial Killer Spirits: Ted Bundy Ritual House’ that took place in Bountiful, Utah: also known as the ‘Anson Call house,’ Zak and his crew went in and investigated the old, abandoned house located in Bountiful, that he claims Ted took Debra Kent to after he abducted her on November 8, 1974… but, come to find out, the house was lived in at the time Kent was abducted from nearby Bountiful High School, so there’s no way he brought her back here to be murdered.

‘New’ Living Victims: in recent years multiple women have come forward claiming to be surviving victims of Ted Bundy, and only recently had the courage to come forward and tell their story: Susan Roller. Sotria Kritsonis. Rhonda Stapley. Sherry Deatrick. Rose Warriner.

Janla Carr: there’s some documents in a FBI file in relation to a woman from Philadelphia that alleged Bundy was her ‘half-brother.’ She also claimed he had a twin brother and made various other assertions about his family history that were widely considered by investigators and psychologists to be ‘unsubstantiated’ and ‘full of leaps.’ She passed away at age 45 in January 1997.