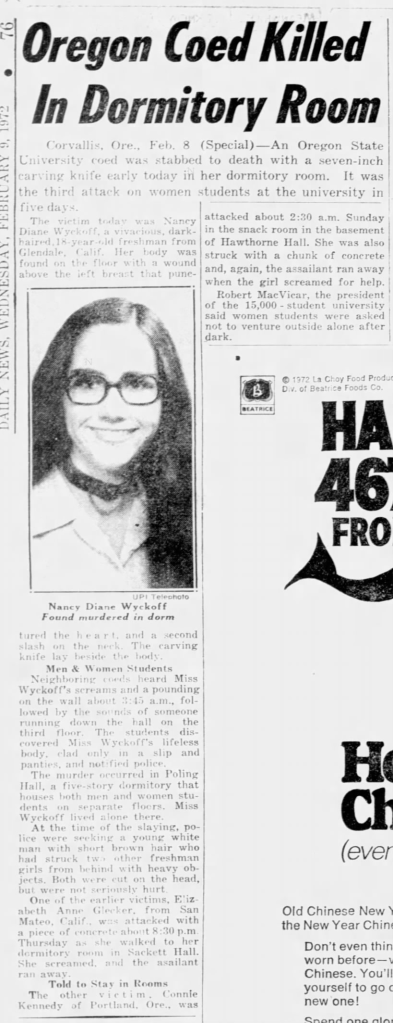

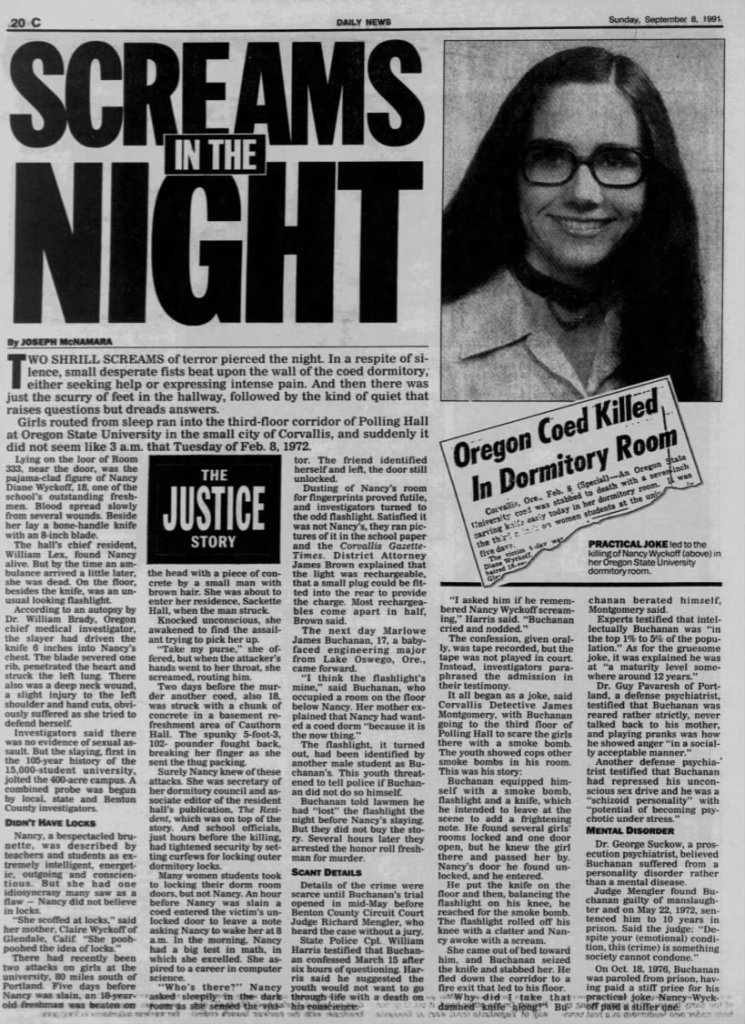

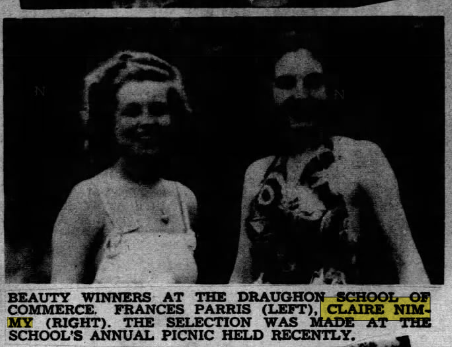

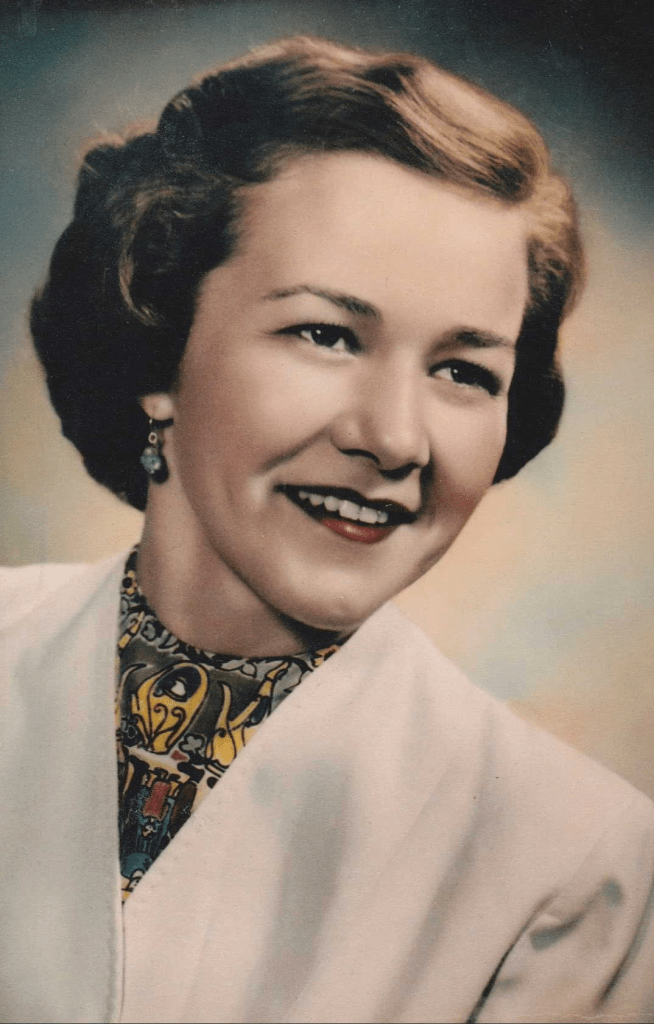

Nancy Diane Wyckoff was born to Brian and Claire (nee Nimmy) in Los Angeles on January 5, 1954 (just as a side note, I’ve seen her referred to as both Nancy and Diane). Mr. Wyckoff was born on June 10, 1927 in LA, and Claire was born on August 11, 1922 in Oak Park, IL; at some point she relocated with her family to Georgia. The couple were wed on May 15, 1953 and settled down in Glendale, California; they had one child together but at some point divorced. Brian married again on July 4, 1958 and had two more children, including Nancy’s half-sister Sarah Wendeline, who was born on August 5, 1963 in San Diego.

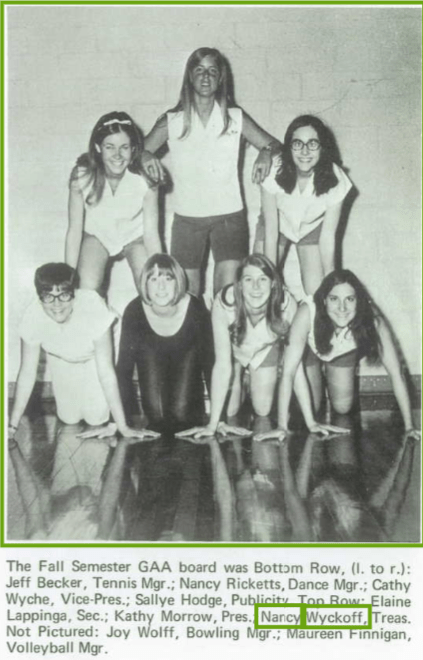

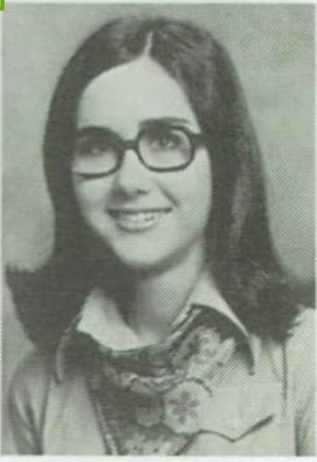

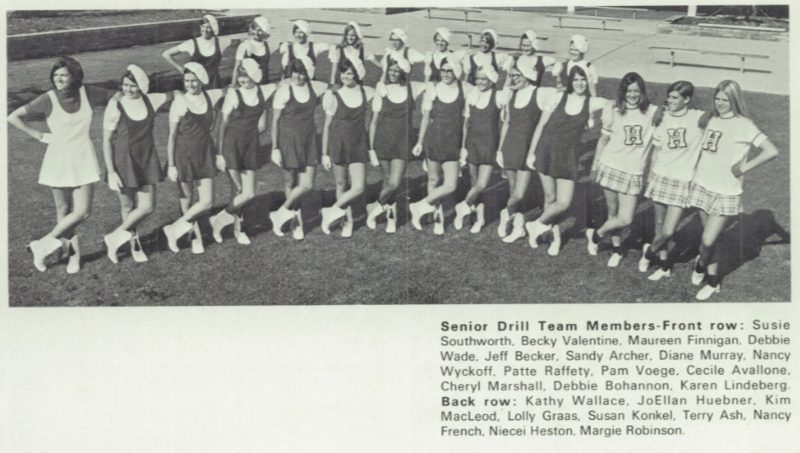

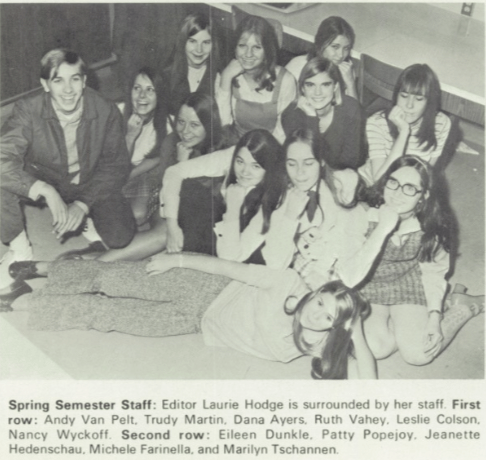

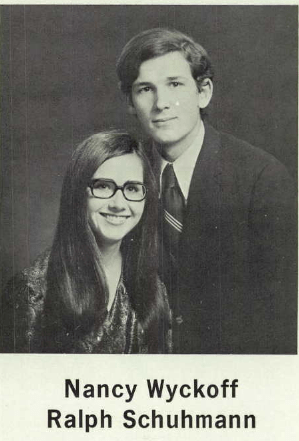

An overall exceptional and bright young woman, Nancy’s parents described her as a diligent and loving child that only wanted the best for herself. She was a 1970 graduate of Herbert Hoover High School, where she was on the senior prom committee, the swim team, and the drill team. Wyckoff was also the Editor-in-Chief of the school newspaper and was secretary of the science club. She maintained a 3.88 GPA and ranked ten out of 490 out of her graduating class, and was considered an excellent, well-rounded young woman. She especially loved math and science, and was a Mu Alpha Theta Jr. Honor Scholar.

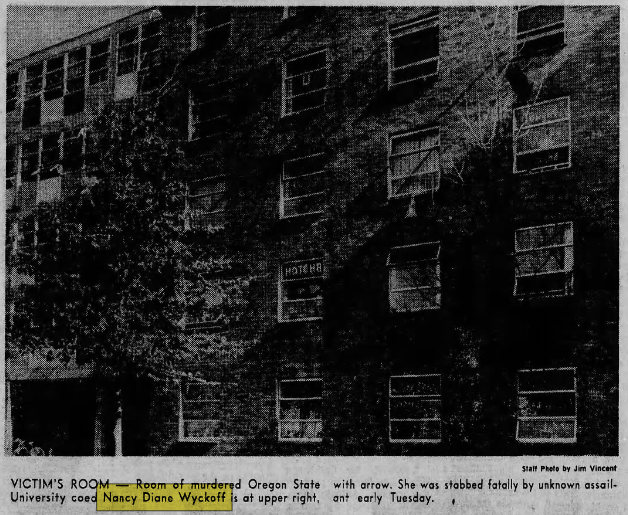

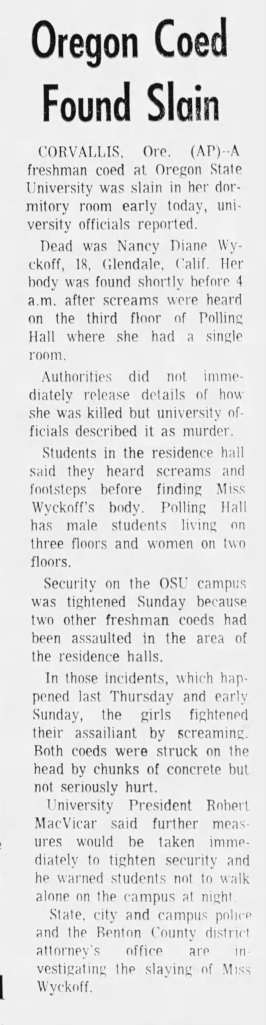

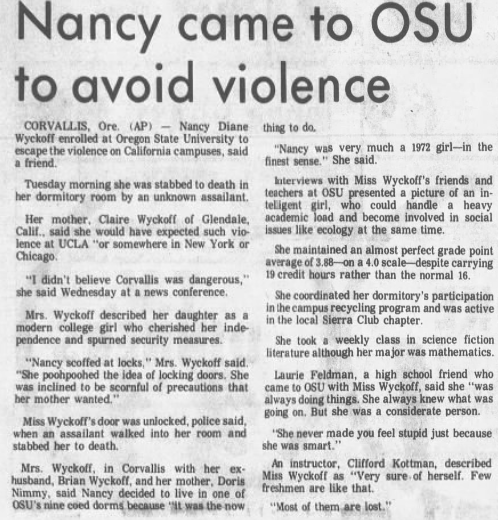

According to her parents, Nancy had an independent streak, and after graduating high school moved to Corvallis, OR where she enrolled at Oregon State University as a mathematics major. She lived in Poling Hall in room 333, and according to an article published in The Olympian, women lived on the first, third, and fourth floors and men lived on the second and fifth floors. Wyckoff was in the honors program, and had received a $1,000 National Merit Scholarship from the Signal Oil Company, where her mother had been employed for 15 years in Glendale. She was interested in politics, nature, and music, and especially loved horseback riding and camping.

Although she dated around, Nancy had no steady boyfriend at the time of her murder, and according to her mother she: ‘choose to live in a coed dorm because it was the ‘now’ thing to do. Nancy was very much a 1972 girl, in the finest sense.’ Taking an impressive 19 credit hours, Wyckoff was the dormitory coordinator of OCU’s recycling program and was active in the school’s Sierra Club, an organization that cherishes and protects natural beauty. A friend of hers from Herbert Hoover High School that also attended Oregon State said that Nancy was ‘always doing things. She always knew what was going on. But she was a considerate person. She never made you feel stupid just because she was smart.’

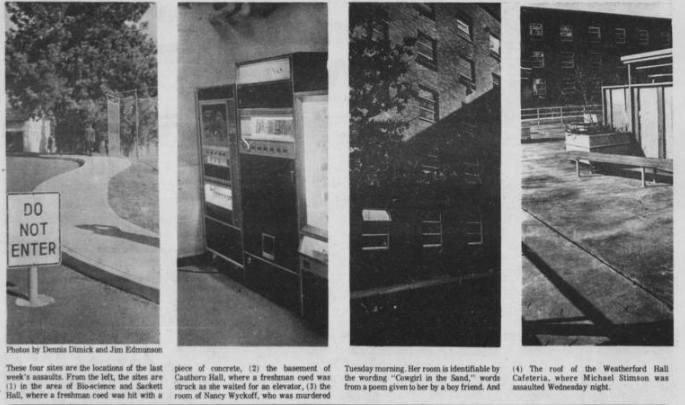

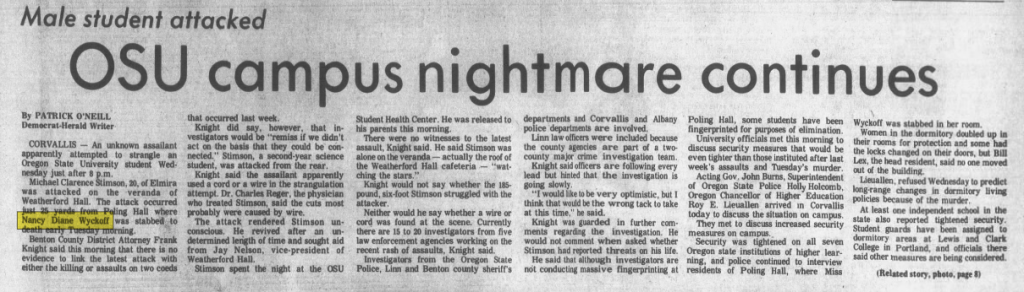

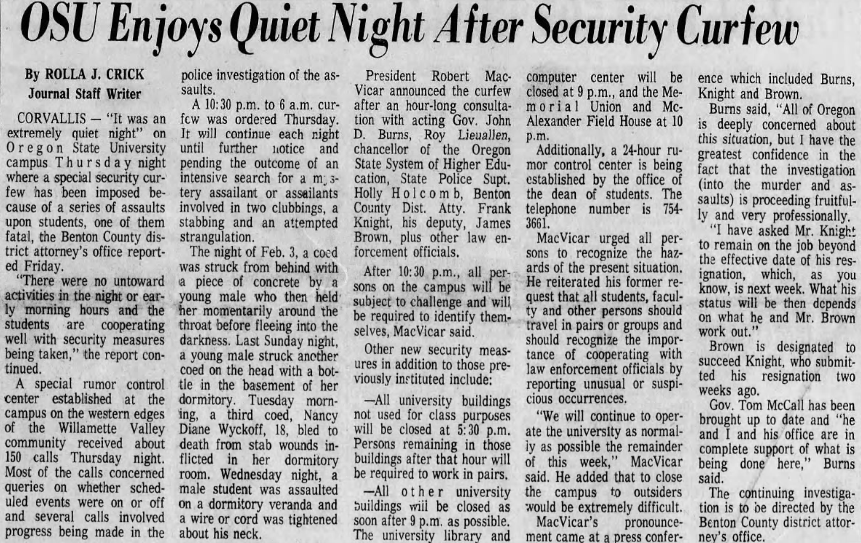

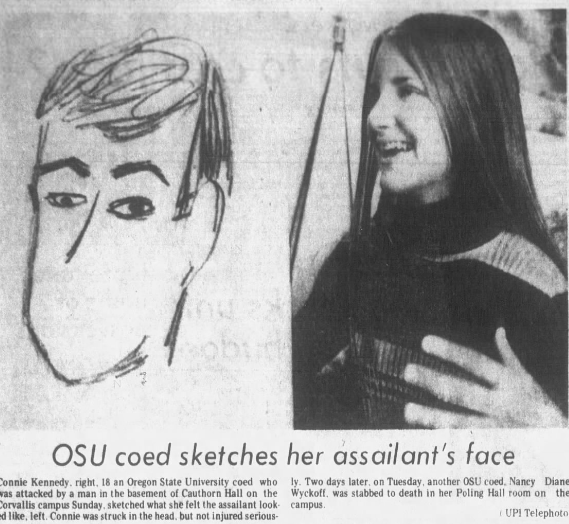

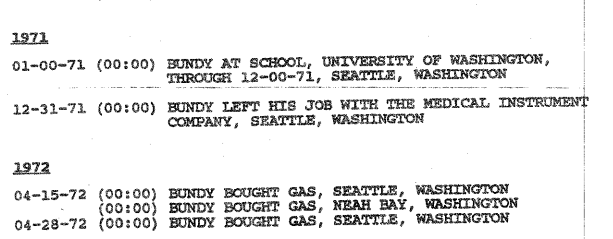

Before Diane’s murder two separate attacks took place on OSU’s campus: at around 8 PM on Thursday, February 3, 1972 a young woman named Elizabeth Ann Gleckler was walking by the Agronomy Building when she got hit in the back of the head with something hard. She fell to the ground and began to scream, which scared off her assailant; she needed stitches and it was eventually determined the weapon her attacker used was a chunk of concrete. Gleckler told campus security that although she didn’t see her assailant’s face she said he was short and young. Just a few days later on February 6, another coed named Connie Kennedy was attacked at around 2:30 AM. She had left her dorm room in Cauthorn Hall and went down to the basement to get a snack from the vending machines, and as she was making her selection felt a blow to the back of her head. A struggle ensued, but thankfully Kennedy was able to get away from her attacker and run away. Like Ms. Gleckler, she didn’t get a good look at her attacker but described him as ‘young, short, brown hair, I think.’

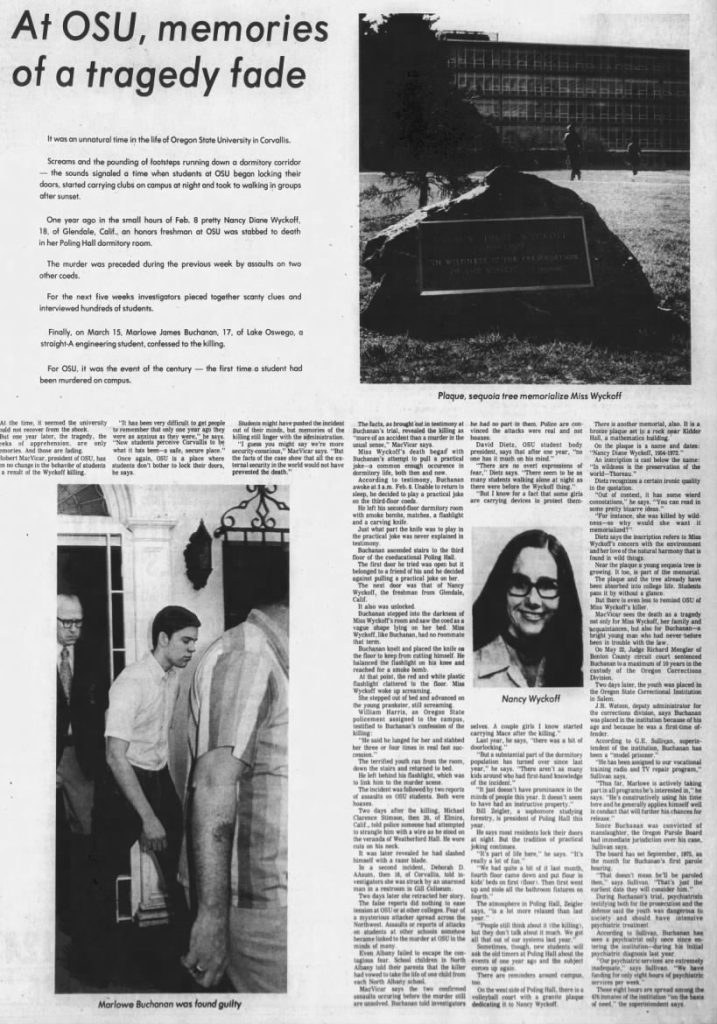

Around 3:45 AM on Tuesday, February 8, 1972 (although I’ve seen it listed as early as 3:00) residents of Poling Hall woke up to two separate screams that came from room 333 on the third floor, then the sound of someone running down the hall and the slam of the north facing fire door. Upon hearing the signs of distress, girls went running to Nancy’s room, and when they arrived they were met with a ghastly sight: Wyckoff’s bare feet, sticking out of the door frame, which prevented it from closing. The clothing on the upper part of her body was saturated in blood, and her head was resting against her bed frame. The young coed was dressed in pajamas, and a large amount of blood had already started to poole underneath her body. Her dorm room was decorated with driftwood and shells she collected from the Oregon coast, which was a popular weekend getaway for OSU students. At the foot of her bed was a poster of a gross green frog with a caption underneath that read: ‘kiss me.’ Her windows had faced the school’s quad, and glued on them were letters that formed the phrase: ‘cowgirl in the sand,’ which is a song by Neil Young that was released in 1969.

The young ladies quickly called the head resident, a young man named William Lex, who ran to Nancy’s room to assess the situation. He knelt beside her, and although she was gravely injured he could still make out faint, shallow breathing. He then made three separate calls: the first to 911 for emergency care, the second to the Corvallis PD, then finally to the OR State Trooper that was assigned to OSU to help augment the university’s police force.

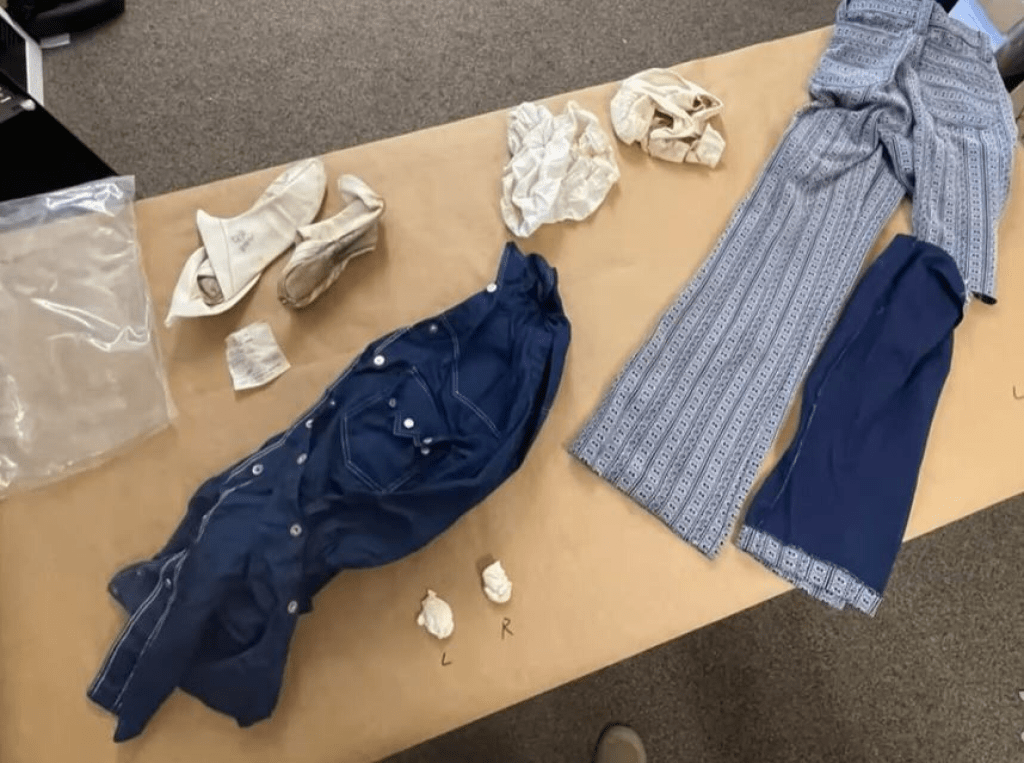

Wyckoff had bled out quickly and it didn’t take long before she succumbed to her injuries; she died before the paramedics arrived. Investigators quickly determined that the young coed had been stabbed, and an 8-inch bone handled carving knife was found lying beside her; its tip was slightly bent. Two foreign hairs had been found in the pool of blood found underneath her. Investigators also found a small, red flashlight that was left behind in Nancy’s bedroom, a type that didn’t take batteries and had a removable portion that could be plugged into a wall and charged, which was missing. Its discovery was initially kept a secret from the public.

Dr. William Brady, who was the Oregon state medical examiner that performed a post mortem examination on Wyckoff, determined that she had suffered three different wounds, and their length and widths all aligned perfectly with the knife that was found left behind at the crime scene. The wound that proved to be fatal penetrated the upper part of her heart, and was six inches long; he said that she ‘she would have succumbed in two or three minutes as a result of this wound. And, it was dealt with considerable force, severing cartilage in its path.’ The second wound entered at the lower part of her neck immediately above the left clavicle and stopped at the top of her right lung. The third was the one that caused the assailant’s knife to bend: it was a shallow wound in her left shoulder, and the only reason it wasn’t deeper is because the shoulder bone is located right below the skin, and it resisted the thrust of the weapon. She was not sexually assaulted in any capacity.

According to those that knew her well, Nancy was a trusting girl, too trusting, and sadly this may have been her downfall: all rooms in her dormitory had locks on them, but she had not utilized hers on the night of her murder. According to Claire Wyckoff, ‘Nancy scoffed at locks. She pooh poohed at the idea of locking doors. She was inclined to be scornful of precautions that her mother wanted.’ After the murder the President of the University ordered a mandatory 10:30 PM curfew on campus: all dorms were to be locked by 7 PM, and all visiting between buildings ceased.

All three policing agencies working the case set up headquarters in the Gill Coliseum on OSU’s campus in order to be close to the investigation, and surprisingly they all seemed to work very well together. Typically LE in the 1970’s didn’t like to share information with each other, and I think of the 1971 murder of Joyce LePage, where the investigation was hindered because the different agencies working the case hoarded information and refused to share it with one another. So much data was collected over the course of Wyckoffs investigation that 1700 pages worth of reports were produced, and the Corvallis Police Sergeant Jim Montgomery (along with his partner, Mel Cofer) alone talked to 199 people during his time working the case.

On February 11, 1972 at roughly 8 PM a young student named Michael C. Stinson stumbled into Weatherford Hall, clutching his neck, barely able to speak. Finally, after much effort he was able to say that as he’d been looking at stars on the veranda of the men’s dorm someone had come up from behind him, slipped a cord around his neck and he subsequently blacked out. Stinson was taken to the Student Health Center where he was evaluated, and physicians said that the pressure from the wire or rope is what made the thin red line left behind on his neck. This only clouded the MO of the sneaky assailant even more.

As the days ticked by and the month of February came to an end, tensions on OSU’s campus lessened somewhat despite no movement being made on the case. On March 1 a decision was made and pictures of a knife that was identical to the one used to kill Wyckoff as well as the recovered flashlight were published in the OSU newspaper along with a plea that anyone that may know more about either to please come forward. When investigators released the picture of the flashlight they left out that it was found in Nancy’s room, and only stated it had been located ‘somewhere in Poling Hall.‘ LE was able to determine that the knife had been made in Japan and came in a kit along with a fork, and where several stores in Corvallis sold these sets unfortunately they didn’t keep records of their customers.

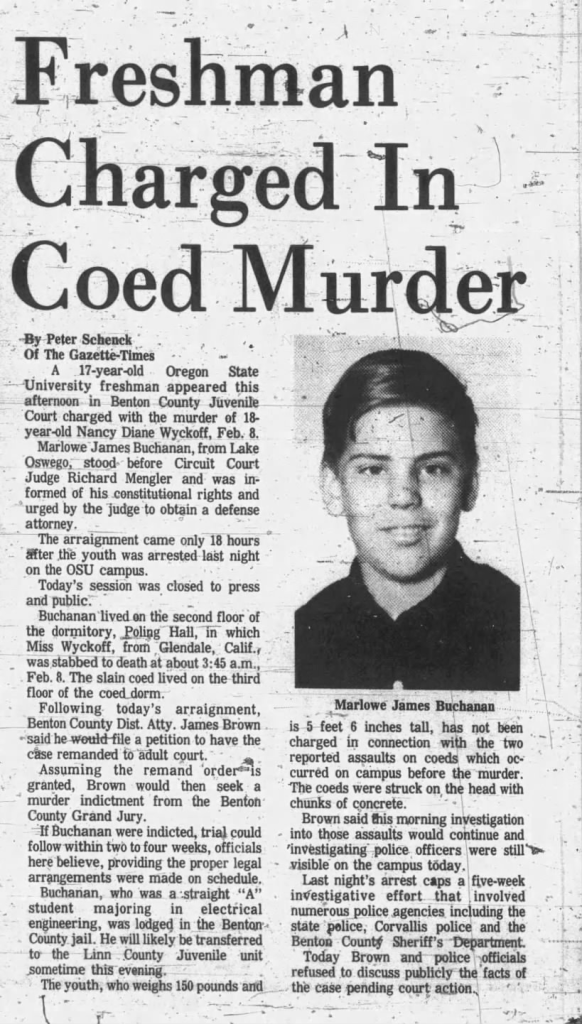

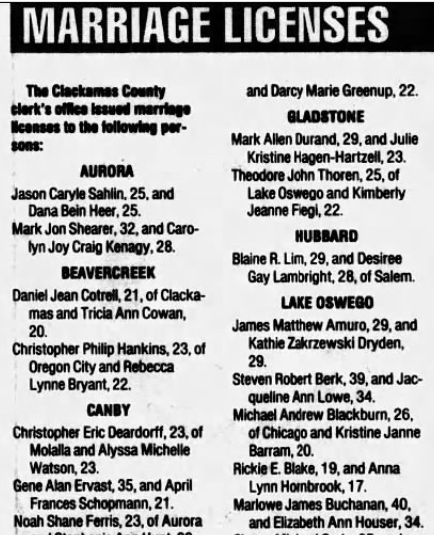

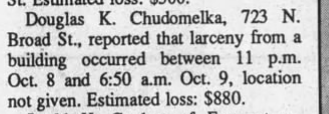

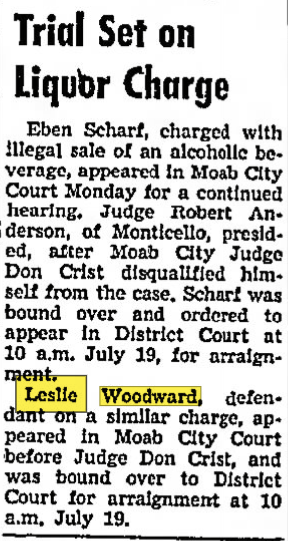

Shortly after the publication a student named Marlowe James Buchanan came forward and told police that he recognized the flashlight, and said: ‘you know, I think that might be my flashlight. I lost it the night before the murder, must have been around 11.’ The young man said that he couldn’t remember exactly where he lost it, but remembered seeing friends on February 7 and surmised that he probably misplaced it then. Buchanan then gave investigators the names of the buddies that he’d been with that night, however they quickly determined that his story had some inconsistencies to them: the boys said they didn’t recall that Marlowe was with them the evening before the murder and that when the article was published he’d asked them not to talk about the fact that he lost his flashlight, and when they asked why, he said ‘its not important, and the police would just bug me about it.’

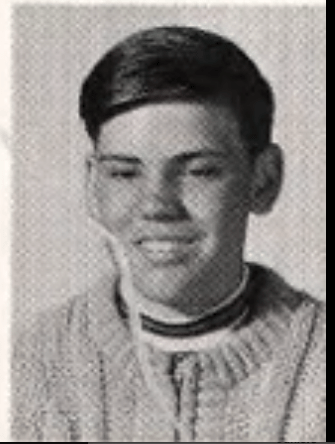

Marlowe James Buchanan was 5’6″ tall and weighed 150 pounds. He maintained a 4.0 average and was known to be brilliant amongst those that knew him, and even graduated from high school a year early after skipping the fifth grade. During an initial interview with investigators, he told them ‘if I’d ever been in her room, it would have been way back at the start of the school year,’ so like all of the other students that admitted to being in Wyckoff’s room, he was fingerprinted. On the third occasion Buchanan spoke with LE he shared: ‘I’ve been thinking, you might find my prints on that fire door. I went up to the third floor to rat fink the girls up there. You know, set off a smoke bomb in the hall. But I changed my mind.’ Investigating officers said he seemed to like talking to them but had a flippant, uncaring facade to him, and that his story wasn’t ‘holding water.’

On March 15, 1972 Benton County Sergeant BJ Miller and his partner Corporal Harris of the Oregon State Police asked Buchanan to come in again to speak to them at their makeshift office in Gill Coliseum. They asked the young man over and over again where the replaceable charging unit had gone from his missing flashlight, and in response he told them that he flushed it down the toilet the morning after the murder because ‘the flashlight was lost, and when something’s gone, it’s gone, so there was no use in keeping the unit.’ He then changed his story, and said he recalled waking up the morning of February 8th feeling that something was ‘terribly wrong,’ and that made him get up, out of bed, and flush the battery down the toilet.

When investigating officers realized that no battery had been found after being disposed of through OSU’s plumbing system, they rushed to the schools custodian, but despite their best efforts the charging unit was gone. Criminologist Bart Reid had done some DNA testing on the hair that was found underneath Wyckoff’s body, and it was determined to be a match to a sample pulled from Buchanan. And Reid’s lab report was shown to the young engineering student, they said to him: ‘we don’t believe you: this report shows you were in her room,’ and his smugness immediately vanished; he still didn’t ask for a lawyer. Harris placed a picture of the murder weapon in front of him and after a while asked, ‘will you go through life with her death on your conscience?” Buchanan began softly crying, and after a few moments he blurted out the entire story.

The young student had been ‘inspired’ by the recent attacks around campus (that he called ‘pranks’), and he wanted to throw the biggest one of all. Buchanan’s previous reference to smoke bombs only alluded to the truth of what really happened: he said he originally intended to scare the young women on the third floor, but the greatest thing he could dream up was to set off one of those bombs inside one of the girls’ rooms, and he only went into Nancy’s because she left it unlocked. He told investigators that he snuck in, knelt beside the sleeping girl, and placed the knife on the floor; he then reached into his pocket for the smoke bomb but as he was fumbling for it the flashlight fell onto the floor, which woke Wyckoff up. He said ‘ I reached for the flashlight but I got the knife instead,’ and when asked (repeatedly) why he needed the piece of cutlery, he never gave detectives a valid answer. When investigators searched Buchanans dormitory they found a set of knives that had one missing, which was a match to the one that was found next to Wyckoff.

Buchanan volunteered that he had been experiencing mental health issues at the time of the incident, and when he went in her room, she woke up, screamed, then quickly ran towards him, which caused him to panic. He said that because he had been raised with ‘conservative values’ he did not want to be caught alone in a female’s bedroom in the early hours of the morning, so he (logically) panicked and ‘unintentionally’ stabbed and killed Nancy in an effort to force her to be quiet.

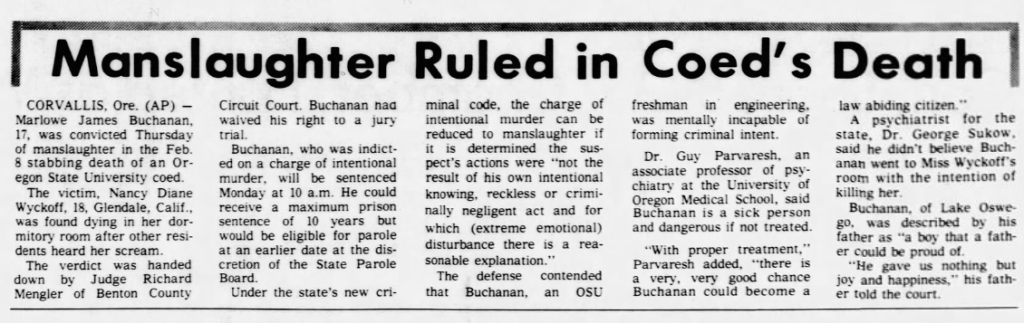

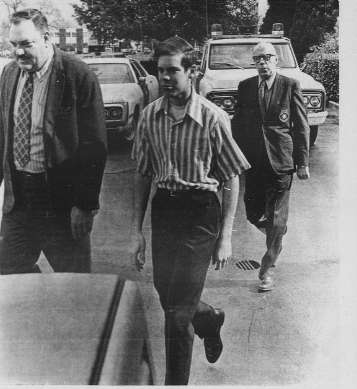

Only four months shy of turning eighteen, Buchanan was quickly transferred out of juvenile court and was tried as an adult. On April 7, 1972 he was indicted on a charge of intentional murder, meaning there was no delegation between first and second degree murder. It is defined as the killing of another person intentionally and is punishable by a minimum of 25 years in prison without parole. The freshman electrical student plead not guilty, citing mental incompetence.

Skilled at chess and bridge, like Nancy Marlowe excelled at math and science, but his social skills and maturity level were not ‘in pace’ with his mind, and he had limited contact with the opposite sex and hadn’t started dating yet. The Buchanan family moved from Southern California to West Oswego, Oregon in 1967 because ‘there were things happening there that we could no longer live with, and we felt the schooling would be better in Oregon.’ He said he had danced with a girl once but that had been the extent of his experience with women, and also suffered from allergies. When asked by a reporter what Marlowe was like, one of his classmates replied with, ‘small thin, slightly built with a baby face and a baby voice.’

Marlowe waived his right to a jury trial and left his fate up to Circuit Court Judge Richard Mengler. Portland based attorneys Nick Chaivoe and Gary Petersen worked for the defense, and at the beginning of the trial Chaivoe said ‘whatever acts were committed were not done in such a way to enforce free will,’ and that Buchanan was ‘suffering from a mental disease or defect and acted without criminal intent.’ No effort was made by the defense to deny that he killed Wyckoff, but psychiatric testimony was introduced which purported that he was a sick person and would be a danger to society if not properly treated.

Doctors that later examined Buchanan dismissed his claims of mental incompetence and determined him to be mentally stable enough to be tried as an adult. The prosecution brought in multiple psychologists to testify on their behalf, all of which reported that he had not been battling any form of mental illness at the time of the homicide but did suggest that he may have been emotionally stressed and had possibly undergone a psychotic break. Experts deemed him to be immature and felt that he panicked beyond the point of rationality at the sound of his victims’ screams, which is why he stabbed her.

During the trial the defense called psychiatrist Dr. Guy Parvarvesh to the stand, who told the court that said ‘Buchanan thought of himself as a normal kid, when instead, he was very shy, introverted. He grew up with the idea that he was in full control, because he never failed at anything he tried.’ He also said that Marlowe developed a schizoid personality, most likely as a result of growing up with a ‘benevolent father and domineering mother. ‘As a result, this led to him ‘having doubts as to his masculinity, and naturally this developed much anger underneath, that he can never admit to anyone or himself.’ The Doctor also said that the defendant enjoyed playing pranks, which was very normal for a person who is ‘sweet on the outside but has anger underneath that can’t be expressed.’ Pranks were a socially acceptable way to express these feelings, while at the same time he was able to relieve these repressed emotions on an unconscious level.’ Dr. Parvarvesh went on to say that ‘Marlowe is a sick person, if he is not treated he will remain a very dangerous person, but if he undergoes extensive psychotherapy, I feel he can become a normal law abiding citizen.’ On Thursday, May 18, 1972 Buchanan received a 10-year prison sentence for the crime, as it was believed he had not entered the room with criminal intent. He was sent to The Oregon Correctional Institute to serve out his sentence.

In June 2024 the Lifetime Network released a made for TV movie (loosely) based on Wyckoff’s murder titled: ‘Danger in the Dorm’ (it’s technically based off of the Ann Rule short story of the same title, to be specific). It stars Bethany Frankel (who got top billing even though the movie is about her daughter, but whatever) and Clara Alexandrova as her daughter Kathleen, a college student that is supposed to be Nancy. While the movie somewhat (mostly) accurately tells Wyckoff’s story, the characters names were obviously changed and there were several occurrences of dramatization that took place. Also, just by watching the trailer, the biggest thing that jumped out at me was: the film takes place today, not in the 1970’s. According to the synopsis on the films IMDB page: ‘after the murder of her childhood best friend and fellow classmate, Kathleen must catch a killer who’s preying on young girls around campus.’ I may or may not watch it later. Stay tuned.

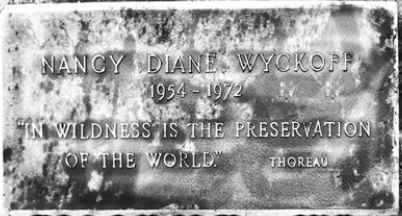

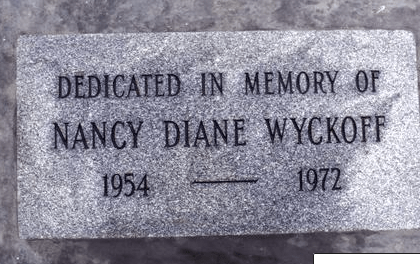

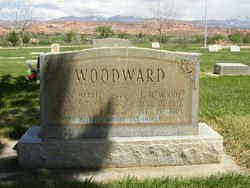

In late February 1972 Nancy’s alma mater of Herbert Hoover High School in Glendale, CA dedicated their journalism room to her memory. In July 1972 students at Oregon State University planted a sequoia tree in her honor in front of Kidder Hall, its plaque reading: ‘Nancy Diane Wyckoff / 1965-1972 / ‘In wilderness is the preservation of the World.’ / -Thoreau.’ Also in the fall of 1972, OSU dedicated their Volleyball Court to Wyckoff’s memory. Brian and Claire Wyckoff established a $1,000 scholarship in their daughter’s honor, and specified that it be divided between a male and female student that were residents of Poling Hall that showed academic excellence along with a financial need. Brian Wyckoff died at the age of 64 on January 10, 1992 and Claire passed at the age of 85 on July 7, 2007. Nancy’s sister Sarah died on April 11, 2023 in San Diego, California.

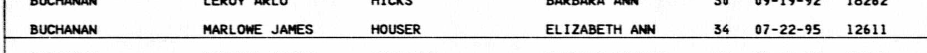

As of December 2024 Marlowe James Buchanan still lives in his hometown of West Oswego, Oregon with his wife, Elizabeth Ann (nee Houser). The couple were married on July 22, 1995 in Washington, OR and have no children. I wasn’t able to find much information about him, but I wasn’t able to find any additional criminal activity linked to him, so he seems to have flown under the radar since being released from prison. He may have gone on to finish his education after he got out of prison, as I found his name linked to some patents that were filed while he was employed at Eaton Intelligent Power Limited. As I found myself digging and digging but still coming up with nothing I suddenly realized that Mr. Buchanan most likely does not want to be found, and I’m going to let him be.

* Just as a side note, I have seen Nancy’s last name spelled Wyckoff and Wycoff; I’m going by the spelling used in almost EVERYTHING, including her high school yearbooks and newspaper articles… although it’s spelled Wycoff on her gravestone (which is actually VERY weird to me, of all the things that it should be correct on it should be that).

Works Cited:

Dawn, Randee. (June 16, 2024). ‘Who killed Nancy Wyckoff? The true story behind Lifetime’s ‘Danger in the Dorm.’’ Taken November 30, 2024 from today.com/popculture/tv/danger-in-the-dorm-true-story-rcna156410

Rule, Ann. (1994). ‘True Crime Archives: Volume One.’

SInha, Shivangi. (June 8, 2024). ‘Nancy Wyckoff Murder: How Did She Die? Who Killed Her?’ Taken November 30, 2024 from thecinemaholic.com/nancy-wyckoff/

Shrestha, Naman. (June 12, 2024). ‘Marlowe James Buchanan: Where is the Killer Now?’ Taken November 30, 204 from thecinemaholic.com/marlowe-james-buchanan/

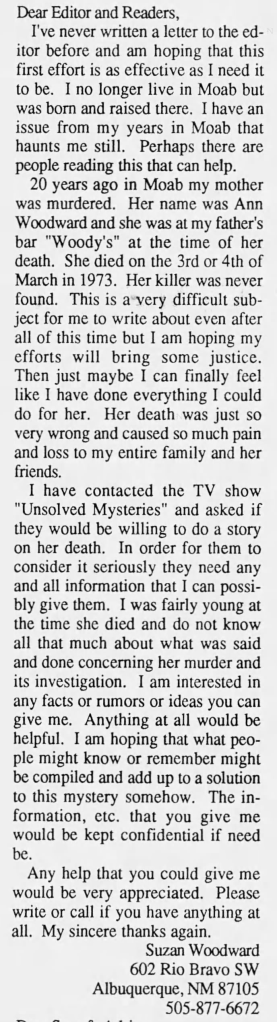

: