Thurston County Sheriff’s Office, documents related to their investigation into William Earl Cosden Jr., Part Six.

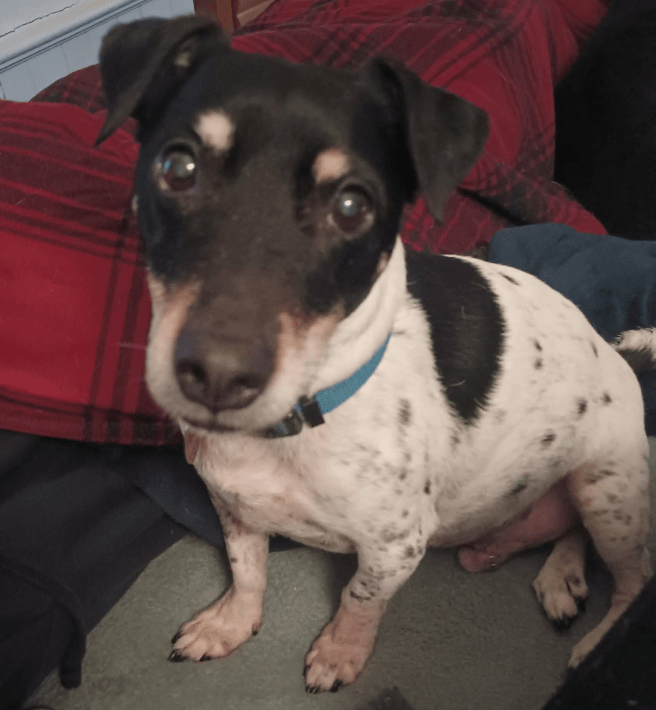

Over the weekend my husband and I had to put our sweet little puppy dog to sleep. In the Spring of 2013 I was volunteering at my local SPCA and there was this little Jack Russell Terrier that kept getting brought back because he wasn’t a typical ‘family dog’ (I won’t lie, he was a grade-A asshole most of the time), so I said I’d bring him home for a (single) weekend that May and I had him ever since. He has been my best friend and has gotten me through some very rough times. As heartbreaking as the experience was, I held my handsome little man while the vet administered the euthanasia, and he laid his little head against my chest and fell asleep forever. I know that’s what HE wanted, and I had to put my sadness aside for him. And as much as I loved him, somehow I think my husband loved him even more. They were best buds.

The People of the state of New York Vs. Joseph Belstadt. Dependent appellant (2025)

Supreme Court, Appellate Division, Fourth Department, New York.

THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK, RESPONDENT, v. JOSEPH H. BELSTADT, DEFENDANT-APPELLANT.

808

Decided: November 21, 2025

PRESENT: MONTOUR, J.P., SMITH, GREENWOOD, NOWAK, AND KEANE, JJ.

THOMAS J. EOANNOU, BUFFALO, FOR DEFENDANT-APPELLANT. BRIAN D. SEAMAN, DISTRICT ATTORNEY, LOCKPORT, FOR RESPONDENT.

MEMORANDUM AND ORDER

It is hereby ORDERED that the judgment so appealed from is unanimously affirmed.

Memorandum: Defendant appeals from a judgment convicting him upon a jury verdict of murder in the second degree (Penal Law § 125.25 [1]). His conviction stems from the disappearance of the 17-year-old victim in September 1993 in Niagara County.

According to witnesses and defendant’s statements to the police after the victim’s disappearance, the victim entered defendant’s car in the early hours of September 19, 1993. The victim’s mother filed a missing person report after she and the victim’s friends were unable to locate her. The victim was discovered deceased in a ravine around a month later, an article of clothing knotted around her neck. According to expert testimony at trial, the victim’s body and clothing reflected signs of a struggle, the cause of her death was asphyxiation by strangulation, and the manner of death was homicide.

In the days following the victim’s disappearance, the police began contacting numerous individuals who had seen her in the days before her death. Given that defendant was the last independently confirmed person to see the victim alive after she got into his car, defendant was determined to be a suspect early in the investigation. Among other things, hundreds of pieces of evidence – hairs, fibers, and other material – were collected from the victim’s body and from vacuuming defendant’s car and sent to the Niagara County Forensic Laboratory. Over the years that followed, evidence was examined and reexamined, analyzed in-house by Niagara County, and contracted out to the Erie County Central Police Services Forensic Science Laboratory as well as labs out of state, and a consultant reviewed evidence in the early to mid-2000s. In 2017, Mark Henderson, a Niagara County forensic analyst who had worked on the case since its inception, reexamined, among other things, a particular hair found in defendant’s car that, in 1997, had been deemed “dissimilar” to the victim’s hair by the Erie County lab that had analyzed it. According to Henderson, by using training and experience he had gathered since that time, he determined that the hair matched the victim’s known pubic hair. Another visually matching hair was then discovered among those collected from defendant’s car. Both pubic hairs were genetically matched to the victim through DNA analysis of the attached root tissue. In addition, around that time, fibers consistent with carpet fibers in defendant’s car were found among the victim’s clothing. Defendant was indicted in April 2018. After lengthy pretrial practice and a mistrial occasioned by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, defendant was tried in 2021 and convicted of murder in the second degree, the sole indicted count. Defendant appeals, and we affirm.

Defendant contends that the conviction is not based on legally sufficient evidence and that the verdict is against the weight of the evidence. Assuming, arguendo, that defendant preserved for our review his challenge to the legal sufficiency of the evidence (see generally People v McGovern, 214 AD3d 1339, 1340 [4th Dept 2023], affd 42 NY3d 532 [2024]), we conclude, after viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the People (see People v Contes, 60 NY2d 620, 621 [1983]), that the evidence is legally sufficient to support the conviction of murder in the second degree (see generally People v Bleakley, 69 NY2d 490, 495 [1987]). Shortly after the victim’s disappearance, defendant himself admitted, and it was independently confirmed by other witnesses, that defendant had given the victim a ride in his car on September 19, 1993, at around 1:30 a.m. Although defendant claimed to have driven her a short distance to the stairs of a nearby church, that claim conflicted with the forensic evidence, namely the victim’s pubic hair found in different locations in defendant’s car. In addition, testimony at trial reflected defendant’s movements and behavior before and after he encountered the victim. After going to a nearby police station to complain about a recent traffic ticket at around 1:00 a.m., defendant declined an invitation to go to Canada with friends, instead opting to drive around because, according to those friends, he was upset over the tickets. While driving, defendant observed the victim and offered to give her a ride. According to his friends, when they returned from Canada, defendant’s car was not parked at his grandmother’s home, where defendant lived, or at his mother’s home. Another witness observed defendant alone in his car, which was wet, and defendant told the witness he had just washed it. In the days after, defendant appeared at various locations in an attempt at establishing a false alibi. He spoke to each of his four friends who had gone to Canada on the night that the victim disappeared, asking them to lie to the police and assert that defendant had gone with them, and defendant was absent from school during the week after the victim’s disappearance. Testimony also reflected that defendant had, in the summer of 1993, driven another young woman to a location near where the victim’s body would later be found. With respect to the element of intent, we note that the victim was found with clothing knotted around her neck, and that expert testimony at trial concluded that the state of her clothing and body reflected homicide by asphyxiation following a struggle. Further, the testimony of an individual who had been incarcerated with defendant on an unrelated charge reflected that defendant had admitted to strangling a girl in the early 1990s and leaving her body outdoors. We further conclude, after viewing the evidence in light of the elements of the crime as charged to the jury (see People v Danielson, 9 NY3d 342, 348 [2007]), that the verdict is not against the weight of the evidence (see People v Monk, 57 AD3d 1497, 1499 [4th Dept 2008], lv denied 12 NY3d 785 [2009]; see generally Bleakley, 69 NY2d at 495).

Contrary to defendant’s further contention, the opinion testimony of the expert pathologist, based upon, inter alia, his review of autopsy materials, was properly admitted at trial and did not violate defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to confrontation (see People v Ortega, 40 NY3d 463, 475-476 [2023]). “[T]he Confrontation Clause does not entirely preclude the use of information contained in testimonial autopsy reports,” and an expert may offer opinions related to the cause and manner of death if the expert has “used their independent analysis on the primary data,” including autopsy photographs, video recordings, and anatomical measurements (id. at 476-477; see People v Austin, 237 AD3d 736, 738 [2d Dept 2025]; People v Taveras, 228 AD3d 410, 412 [1st Dept 2024], lv denied 42 NY3d 1054 [2024]; People v Rivers, 225 AD3d 899, 901-902 [2d Dept 2024], lv denied 42 NY3d 929 [2024]). Here, the record reflects that the testifying expert, who did not perform or observe the autopsy, reached his conclusions based on an independent review of the proper materials rather than the conclusions of the performing medical examiner (see Austin, 237 AD3d at 738; cf. Ortega, 40 NY3d at 478).

We likewise reject defendant’s contention that his due process right to prompt prosecution was violated by the preindictment delay. In determining whether defendant was deprived of due process, we must consider the factors set forth in People v Taranovich (37 NY2d 442 [1975]), which are: “(1) the extent of the delay; (2) the reasons for the delay; (3) the nature of the underlying charge; (4) whether ․ there has been an extended period of pretrial incarceration; and (5) whether ․ there is any indication that the defense has been impaired by reason of the delay” (id. at 445; see People v Johnson, 39 NY3d 92, 96 [2022]). These factors must be reviewed “in light of the particular factors attending to the specific case under scrutiny ․, there are no clear cut answers in such an inquiry, ․ [and] no one factor or combination of the factors ․ is necessarily decisive” (Taranovich, 37 NY2d at 445).

Although the delay in this case was substantial, the nature of the underlying charge was serious and defendant was not arrested on that charge until he was indicted (see People v Rogers, 103 AD3d 1150, 1151 [4th Dept 2013], lv denied 21 NY3d 946 [2013]). Moreover, although the delay in this case may have caused some degree of prejudice to defendant, the People satisfied their burden of demonstrating good cause for the delay (see id.; People v Chatt, 77 AD3d 1285, 1285 [4th Dept 2010], lv denied 17 NY3d 793 [2011]). Of note, the People submitted a sworn affidavit from Henderson, which presented a narrative of the investigative events since 1993, discussed the thousands of hours dedicated to the case, addressed the outside labs and consultants used to assist in bringing the investigation to a resolution, and explained the limitations of analyzing hundreds of car sweepings (see generally People v Johnson, 211 AD3d 1633, 1634 [4th Dept 2022], lv denied 39 NY3d 1111 [2023]). Contrary to defendant’s related contention, there was no need for a Singer hearing (see People v Singer, 44 NY2d 241, 255 [1978]) inasmuch as the record provided the court with “a sufficient basis to determine whether the delay was justified” (People v Ballowe, 173 AD3d 1666, 1668 [4th Dept 2019] [internal quotation marks omitted]; see Rogers, 103 AD3d at 1151; People v Gathers, 65 AD3d 704, 704 [2d Dept 2009], lv denied 13 NY3d 859 [2009]).

Entered: November 21, 2025

Ann Dillon Flynn

Clerk of the Court

I’ve had Martha Feldman’s rape report in my drafts folder for over a year now, and I’m not sure why I didn’t post it yet. I started doing some digging into her background and as I was really getting into it, I realized that she didn’t ask for this to happen and this file was most likely only released due to a TB related FOIA request: she doesn’t want her personal life to be dissected fifty years after what was most likely one of the worst events of her life, so I am not going to go into her background and will strictly stick to the facts on the police report (especially since she specifies in it that she wishes to remain anonymous). I will say that she went on to lead an incredibly successful life, but I’m not going to elaborate any further. Feldman isn’t a Rhonda Stapley or Sotria Kritsonis, who ‘came forward’ years after their alleged run-in’s with Bundy looking for attention and notoriety (and in Stapley’s case, money). I mean, there’s a fair chance that Ted wasn’t Martha’s rapist.

According to the police report that Feldman filed on March 7, 1974 with the Seattle Police Department at the YWCA (located at 4224 University Way NW), she was raped by an unnamed assailant five days prior on Saturday, March 2 around 4:15 AM; she first disclosed her attack to a woman named Maria at the Seattle based organization ‘Rape Relief’ later that morning at around 7:30; from there, she sent two young women over, and they brought her into Harborview Hospital for a medical exam, which was given by a Dr. Shy at around 8:30 AM (where we know Bundy interned as a counselor from June 1972 to September 1972); the Seattle PD were notified later that evening.

Feldman told investigators that at around 1:30 AM on February 28, 1974 she heard something unusual but when she got up to investigate nothing was amiss; later in the same afternoon a friend of hers noticed that the screen had been removed from one of her windows (this reminds me of when Ted removed Cheryl Thomas’s screen from her window four years later in Florida). Martha’s assailant broke into her apartment around 4 AM and said that he didn’t ask her for money or valuables, and she even had some of her good jewelry sitting out and it remained untouched (in fact, the man didn’t appear to touch anything in the apartment). Personally, I think it makes sense that Bundy wouldn’t have stolen anything expensive, because by that point Liz already knew he was stealing and he was making a half-hearted attempt of not doing it.

Also, according to the report Feldman was moving out of her apartment and would be in touch with her new address; it does not clarify if she left because of her rape. She did not want her parents notified of her assault and said that she was ‘careless in not drawing her drapes or locking the window.’ After a few unsuccessful attempts to reach her by phone, detectives finally connected with her and on March 6th stopped by her apartment so she could sign a medical release form and speak to her more about what happened. Feldman told them that her assailant had been between twenty to twenty-four years old based off his ‘build and voice,’ and said that she never saw his face because he had a dark navy watch cap pulled over his head and down below his chin (it only had slits for the eyes that she suspected were made by him and specified that it had ‘not been a ski mask’); she said that she didn’t know his hair color but was certain he was white because she ‘saw his arms’ (she also said they had no hair on them).

Feldman said that early on the Saturday morning of her assault she went to bed around 1 AM (one other place in the police report said it was at 2 PM), and even though her shades were drawn one of the curtains were slightly agape, and she said it was easy to look in her one window and see that her extra bed was empty and that she was alone (she said that roughly ¾ of the time a friend stayed with her). It was probably 4 AM when she was suddenly awakened by something (she believes by him opening then shutting the window). Martha said that she’ had forgot to put the wooden slot in the window to lock it and although it would be difficult to see it was not there in the dark, he must have seen it as be took off the outer screen to reach the window.’ When she opened her eyes, a man she didn’t immediately recognize was standing in her doorway, and she said at first she only saw his profile and noticed there was something bright illuminating her living room and realized he had left his flashlight on the table (and that he had left it on). After her assailant came in her room he sat on her bed and assured her that he wasn’t going to hurt her and that he wouldn’t use his weapon on her as long as she didn’t scream, then proceeded to pull a hunting knife out from his back pocket, one that was dark and had a ‘carved bone handle’ with streaks on it. When she asked him how he got into her apartment he told her that it was ‘none of her business.’

Martha told the detectives that the man had been wearing a white, short-sleeved t-shirt and Levi’s, but was wearing not wearing a coat or sweater (even though it had been cold outside). She also said that his voice sounded like a Northwesterner and he seemed ‘well-educated,’ and possibly could have been a student at the nearby University of Washington. Feldman said that she didn’t recall that her assailant was wearing any jewelry or a watch and he had been drinking but was ‘not drunk’ and after about eight to ten minutes of talking he pulled out some tape out of his pocket and used it to cover her eyes.

He then turned on her bedroom light and left it on as he undressed her, unzipped his pants, then had sexual intercourse with her. When finished, he taped her hands and feet up ‘just to slow you down,’ turned off the light, covered her up with some blankets, said ‘go back to sleep,’ then left; the tape was later put into evidence. She heard him go out to the living room, open the window then run down the back alley; she listened but heard no car start up. Martha said he was very calm and sure of himself and felt that ‘he has done this before,’ although he didn’t say anything that made her think it was anything other than his first time. Feldman told detectives that she believed she could identify her assailant (even though her eyes were taped shut), and was usually home days as she had classes in the evening.

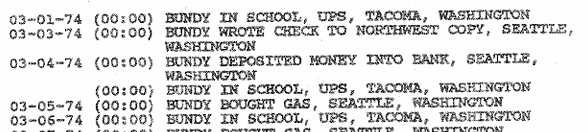

At the time of her assault Feldman lived at 4220 12th Avenue NE Unit 14, which was four houses and just a minute’s walk away for Bundy, who was living at the Rogers Rooming House just down the street at 4214 12th Ave NE (the building she lived in has since been torn down and in 2023 a new complex was built in its place). Ted’s whereabouts aren’t accounted for specifically on March 2, 1974, however he was placed in Seattle/Tacoma both the day before and after. He was in between employment at the time and had been without a job since September of 1973 (when he was the Assistant to the Washington State Republican chairman) and remained unemployed until May 3, 1974 when he got a position with the Department of Emergency Services in Olympia (he was there until August 28, 1974, which is right before he left for law school). On the last page of the eight-page document is a blank page with a scribbled note: ‘this is the case, I thought of for Bundy. Think there would be a print on the tape?’

Bundy went on to abduct then murder Donna Gail Manson from Evergreen State College in Olympia on March 12, 1974. On her website ‘CrimePiper, Erin Banks points out that on a social media post about Feldman one commenter remarked on the face that the assailant pulled out a ‘carved knife handle,’ and it just so happened to match the description of a rare knife that had been ‘stolen’ out of Bundy’s girlfriend Elizabeth Kloepfer’s VW Bug a short period later. That same person went on to say that ‘the fact that he wasn’t wearing a jacket, just a T-shirt, even though it was cold outside, seems to indicate he lived nearby too.’

Documents related to Ramon Benavides, Kittitas County Undersheriff during the Ted Bundy Investigation.