Thurston County Sheriff’s Office, documents related to their investigation into William Earl Cosden Jr., Part Six.

I’ve had Martha Feldman’s rape report in my drafts folder for over a year now, and I’m not sure why I didn’t post it yet. I started doing some digging into her background and as I was really getting into it, I realized that she didn’t ask for this to happen and this file was most likely only released due to a TB related FOIA request: she doesn’t want her personal life to be dissected fifty years after what was most likely one of the worst events of her life, so I am not going to go into her background and will strictly stick to the facts on the police report (especially since she specifies in it that she wishes to remain anonymous). I will say that she went on to lead an incredibly successful life, but I’m not going to elaborate any further. Feldman isn’t a Rhonda Stapley or Sotria Kritsonis, who ‘came forward’ years after their alleged run-in’s with Bundy looking for attention and notoriety (and in Stapley’s case, money). I mean, there’s a fair chance that Ted wasn’t Martha’s rapist.

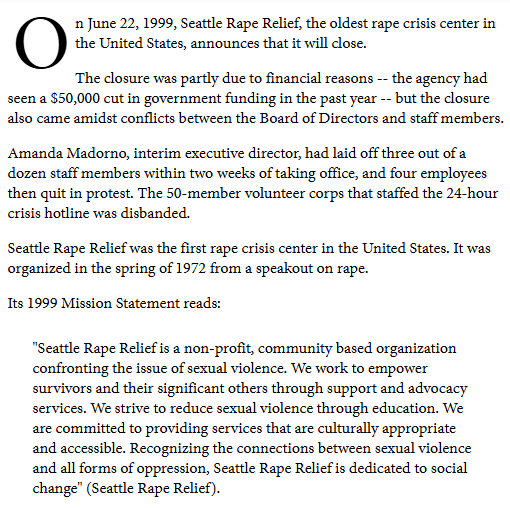

According to the police report that Feldman filed on March 7, 1974 with the Seattle Police Department at the YWCA (located at 4224 University Way NW), she was raped by an unnamed assailant five days prior on Saturday, March 2 around 4:15 AM; she first disclosed her attack to a woman named Maria at the Seattle based organization ‘Rape Relief’ later that morning at around 7:30; from there, she sent two young women over, and they brought her into Harborview Hospital for a medical exam, which was given by a Dr. Shy at around 8:30 AM (where we know Bundy interned as a counselor from June 1972 to September 1972); the Seattle PD were notified later that evening.

Feldman told investigators that at around 1:30 AM on February 28, 1974 she heard something unusual but when she got up to investigate nothing was amiss; later in the same afternoon a friend of hers noticed that the screen had been removed from one of her windows (this reminds me of when Ted removed Cheryl Thomas’s screen from her window four years later in Florida). Martha’s assailant broke into her apartment around 4 AM and said that he didn’t ask her for money or valuables, and she even had some of her good jewelry sitting out and it remained untouched (in fact, the man didn’t appear to touch anything in the apartment). Personally, I think it makes sense that Bundy wouldn’t have stolen anything expensive, because by that point Liz already knew he was stealing and he was making a half-hearted attempt of not doing it.

Also, according to the report Feldman was moving out of her apartment and would be in touch with her new address; it does not clarify if she left because of her rape. She did not want her parents notified of her assault and said that she was ‘careless in not drawing her drapes or locking the window.’ After a few unsuccessful attempts to reach her by phone, detectives finally connected with her and on March 6th stopped by her apartment so she could sign a medical release form and speak to her more about what happened. Feldman told them that her assailant had been between twenty to twenty-four years old based off his ‘build and voice,’ and said that she never saw his face because he had a dark navy watch cap pulled over his head and down below his chin (it only had slits for the eyes that she suspected were made by him and specified that it had ‘not been a ski mask’); she said that she didn’t know his hair color but was certain he was white because she ‘saw his arms’ (she also said they had no hair on them).

Feldman said that early on the Saturday morning of her assault she went to bed around 1 AM (one other place in the police report said it was at 2 PM), and even though her shades were drawn one of the curtains were slightly agape, and she said it was easy to look in her one window and see that her extra bed was empty and that she was alone (she said that roughly ¾ of the time a friend stayed with her). It was probably 4 AM when she was suddenly awakened by something (she believes by him opening then shutting the window). Martha said that she’ had forgot to put the wooden slot in the window to lock it and although it would be difficult to see it was not there in the dark, he must have seen it as be took off the outer screen to reach the window.’ When she opened her eyes, a man she didn’t immediately recognize was standing in her doorway, and she said at first she only saw his profile and noticed there was something bright illuminating her living room and realized he had left his flashlight on the table (and that he had left it on). After her assailant came in her room he sat on her bed and assured her that he wasn’t going to hurt her and that he wouldn’t use his weapon on her as long as she didn’t scream, then proceeded to pull a hunting knife out from his back pocket, one that was dark and had a ‘carved bone handle’ with streaks on it. When she asked him how he got into her apartment he told her that it was ‘none of her business.’

Martha told the detectives that the man had been wearing a white, short-sleeved t-shirt and Levi’s, but was wearing not wearing a coat or sweater (even though it had been cold outside). She also said that his voice sounded like a Northwesterner and he seemed ‘well-educated,’ and possibly could have been a student at the nearby University of Washington. Feldman said that she didn’t recall that her assailant was wearing any jewelry or a watch and he had been drinking but was ‘not drunk’ and after about eight to ten minutes of talking he pulled out some tape out of his pocket and used it to cover her eyes.

He then turned on her bedroom light and left it on as he undressed her, unzipped his pants, then had sexual intercourse with her. When finished, he taped her hands and feet up ‘just to slow you down,’ turned off the light, covered her up with some blankets, said ‘go back to sleep,’ then left; the tape was later put into evidence. She heard him go out to the living room, open the window then run down the back alley; she listened but heard no car start up. Martha said he was very calm and sure of himself and felt that ‘he has done this before,’ although he didn’t say anything that made her think it was anything other than his first time. Feldman told detectives that she believed she could identify her assailant (even though her eyes were taped shut), and was usually home days as she had classes in the evening.

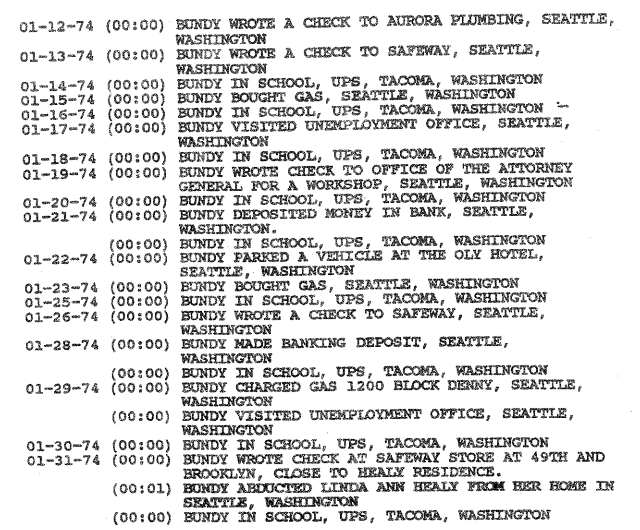

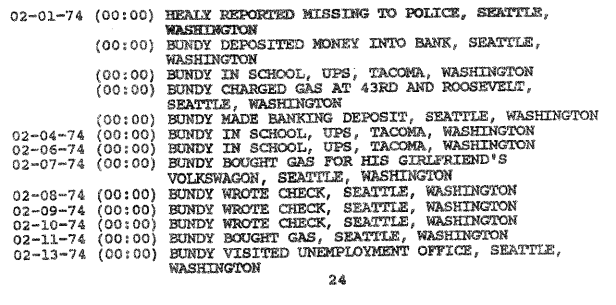

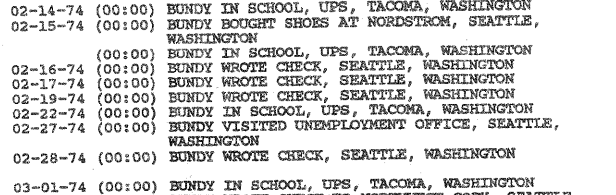

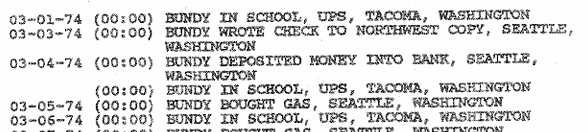

At the time of her assault Feldman lived at 4220 12th Avenue NE Unit 14, which was four houses and just a minute’s walk away for Bundy, who was living at the Rogers Rooming House just down the street at 4214 12th Ave NE (the building she lived in has since been torn down and in 2023 a new complex was built in its place). Ted’s whereabouts aren’t accounted for specifically on March 2, 1974, however he was placed in Seattle/Tacoma both the day before and after. He was in between employment at the time and had been without a job since September of 1973 (when he was the Assistant to the Washington State Republican chairman) and remained unemployed until May 3, 1974 when he got a position with the Department of Emergency Services in Olympia (he was there until August 28, 1974, which is right before he left for law school). On the last page of the eight-page document is a blank page with a scribbled note: ‘this is the case, I thought of for Bundy. Think there would be a print on the tape?’

Bundy went on to abduct then murder Donna Gail Manson from Evergreen State College in Olympia on March 12, 1974. On her website ‘CrimePiper, Erin Banks points out that on a social media post about Feldman one commenter remarked on the face that the assailant pulled out a ‘carved knife handle,’ and it just so happened to match the description of a rare knife that had been ‘stolen’ out of Bundy’s girlfriend Elizabeth Kloepfer’s VW Bug a short period later. That same person went on to say that ‘the fact that he wasn’t wearing a jacket, just a T-shirt, even though it was cold outside, seems to indicate he lived nearby too.’

Document courtesy of the King County Sheriff’s Department. Over the years Karen has been given various pseudonyms, including ‘Joni Lenz,’ ‘Mary Adams,’ and ‘Terri Caldwell’ (in an attempt to protect her identity) and told her story for the first time in the 2020 Amazon docuseries, ‘Ted Bundy: Falling for a Killer.’

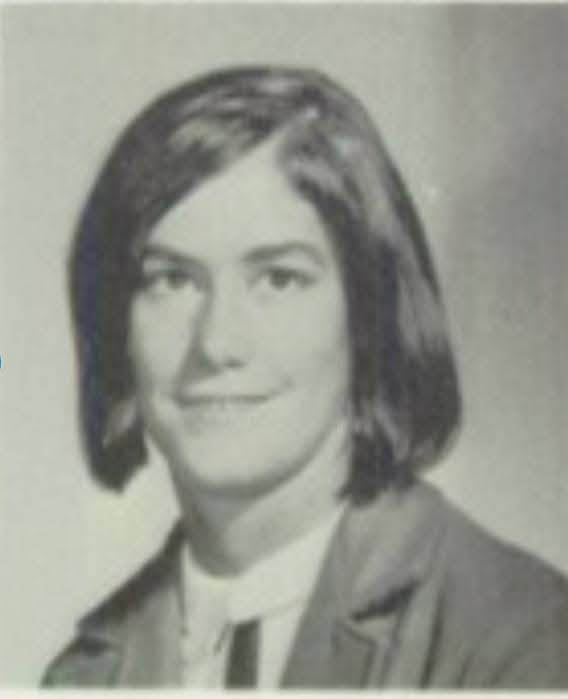

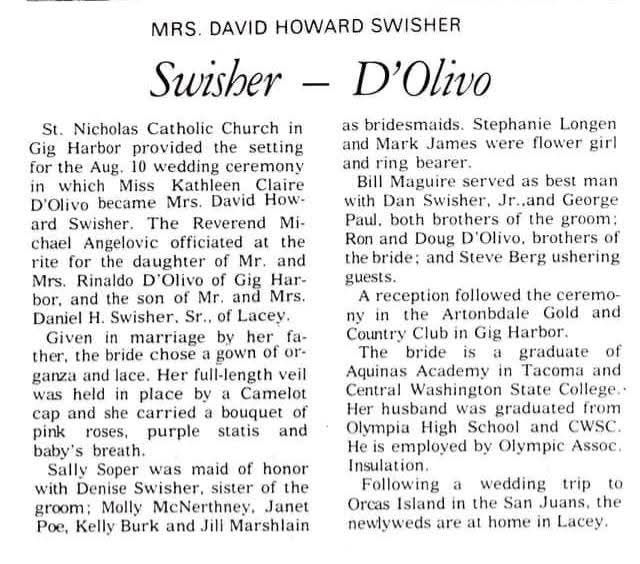

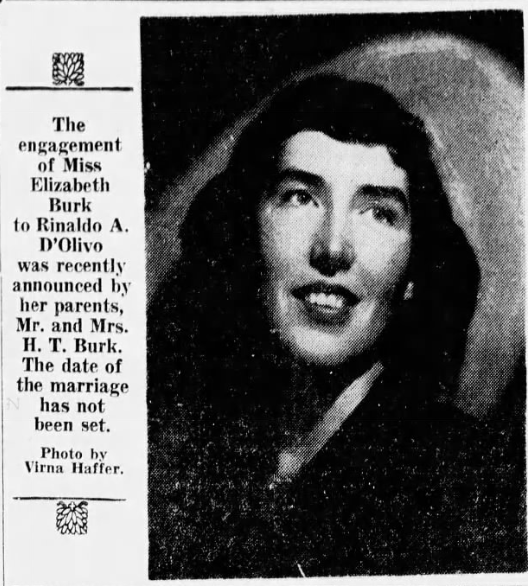

This is the second in a series about young women that were encountered by Ted Bundy on the Central Washington University campus in April 1974: Kathleen Clara D’Olivo was born on October 8, 1952 to Rinaldo and Elizabeth (nee Burk) D’Olivo in Tacoma WA. Rinaldo Anthony ‘Buzz’ D’Olivo was born on January 13, 1928 in Tacoma, and after graduating from Bellarmine Prep he served in the military during WWII; upon returning home he enrolled at Gonzaga University as a marketing major, and in 1974 he founded the company ‘Humdinger Fireworks.’ Kathy’s mother Elizabeth ‘Betty‘ Ann Burk was born on May 9, 1930 in Clare, Iowa. The couple were married on August 26, 1950 and went on to have three children together: Kathy, Douglas (b. 1954), and Rinaldo (b. 1956).

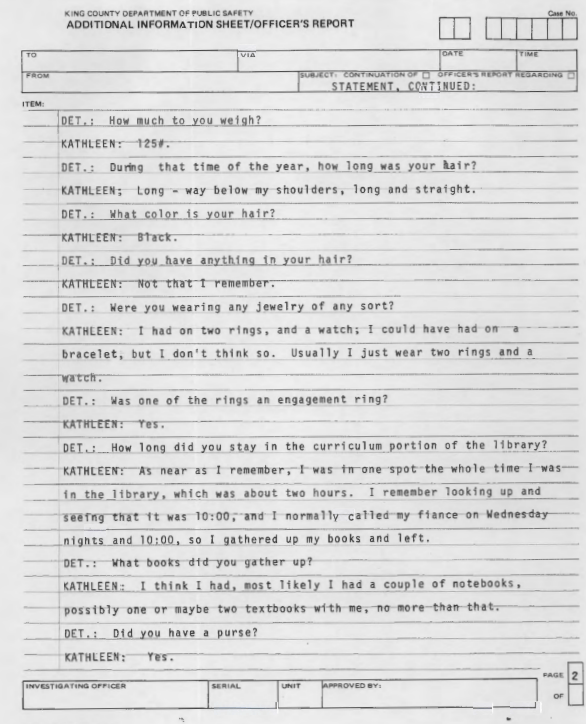

A traditional Italian beauty, Kathy was tall and slim, and stood at 5′ 9.5″ and weighed 125 pounds; she had hazel eyes and dark brown hair she wore long and parted down the middle. At the time of her encounter, she was living with a roommate in unit #21 at the Knissen Village Apartments located on 14th and ‘B’ Street.

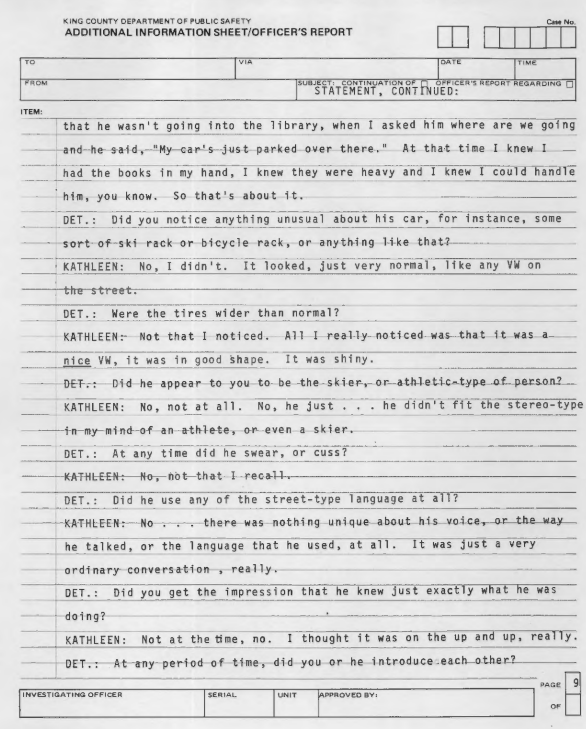

On the evening of Wednesday, April 17, 1974, twenty-one-year-old D’Olivo dropped her roommate off near downtown Ellensburg and drove to CWU’s campus, arriving just after 8:00 PM; she parked her car in the lot next to the Hertz Music Hall (located kitty corner to the library) and went into the main entrance of the Bouillon Library. In an interview with Detective Robert Keppel of the King County Sheriff’s Department on March 1, 1975, Kathleen said that ‘it was a clear night. I don’t remember it being extremely cold or extremely warm.’ She also stated that she was certain she was wearing blue jeans but wasn’t 100% sure of the top she had on, however she thinks it was most likely a blazer. Kathy was wearing two rings (one of them being her engagement ring) and said that she may have also been wearing a bracelet; at the time she was using a navy-blue cross-body purse.

Kathy stayed on the second floor of the library until around 10 PM, studying in an area known as the curriculum laboratory (don’t forget this location, I’m going to bring it up again later). But when she saw the clock nearing 10, she began gathering up her things, as it was time to head home and call her fiancé (a ritual she did every Wednesday at the same time). D’Olivo left the library same way she came in: through the front entrance. She then made a quick right and stepped off the concrete path and began making her way across the grass.

D’Olivo said that she ‘hadn’t quite gotten off the lawn, or sidewalk (wherever I was, I hadn’t reached the main mall stretch) when I heard something behind me. It sounded like something following me, it didn’t startle me or anything, it wasn’t a loud noise and I turned around and there was a man dropping books, he was squatting, trying to pick up the books and packages was what he was doing and so I noticed that he had a sling on one arm, and a hand brace on the other. I didn’t really notice it at the time, I just noticed that he was unable to pick up that many things and I assumed that he was going into the library. I went over and said, ‘do you need help?’ He said, ‘Ya, could you?,’ or something to that affect. So I picked up what to me felt like a bicycle backpack, it was nylon material, kind of.’ Kathy later clarified that he had his right arm in a sling but had metal braces on fingers of both hands, specifically the type that were used on broken fingers.

Kathleen told Detective Keppel that she wasn’t sure what was in the backpack, but it felt like books, and he also had with him ‘some packages, three boxes that were small, not large. I think they were wrapped in parcel post, or brown paper bag-type thing and I think some of them had string ties on them, you know, like… I’m almost sure on that, but at any rate, I picked up the bag that I thought had books in it, the knapsack type bag, and he picked up the packages.’

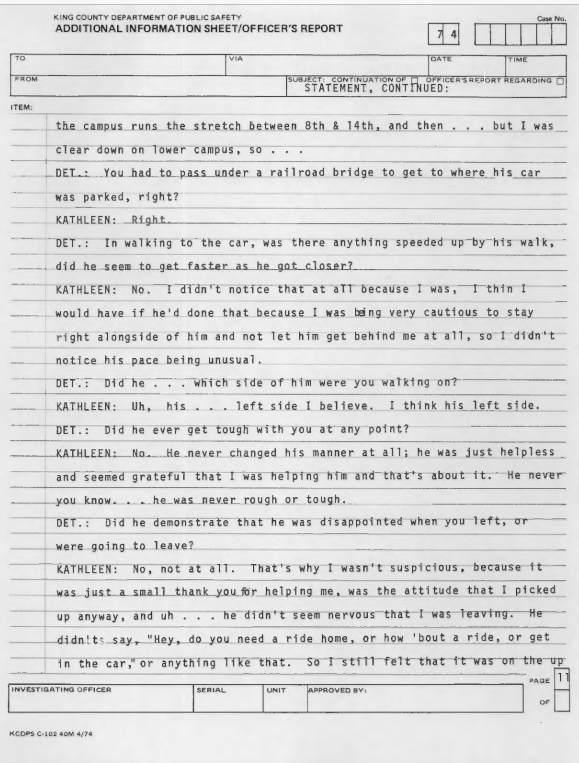

When Detective Keppel asked Kathy where she thought he was taking her as they began their walk, she replied ‘I thought he was going in the library. He was headed that way, so I thought that’s where he was going. But that same sidewalk actually leads up over a little bridge that runs alongside the library, it’s just short bridge that goes over a pond (man-made pond) and that’s actually the direction that he was going in, but its right next to the library and the same sidewalk will angle off to go into the library so that’s where I thought he was going. We started walking and when we came to the bridge, it was obvious that he wasn’t turning off to go to the library, and I said wait a minute, you know, where are we going? He said, ‘oh my car is just parked right over here.‘ I said okay, or didn’t make any motion, but at the same time I know what I was carrying which I thought was books, or felt like books, was very heavy, and the way I was carrying them, I knew I could protect myself with it if the need arose.’

But instead of continuing on the pathway to the Library, the man started walking across the bridge, which immediately threw up a red flag for D’Olivo, and she said to him, ‘well, wait a minute, were are you going?’ He said, ‘well my cars just over here.’ I said, ‘okay,’ so we started walking across the bridge and we were maybe a quarter the way across the bridge and he began telling me about his ski injuries and that conversation took us up to by the other side of the bridge and a little ways beyond that, and then I asked him again, ‘well, where’s your car?’ I expected it to be parked on the street that’s right behind the library. He said, ‘oh, its just right here.’ Then we walked under the trestle to the right there, and it was just barely down that dark stretch.’ She said at that time she ‘assessed the situation,’ and said she ‘was extremely cautious while with him. I never gave him the opportunity of walking behind me.’

When Detective Keppel asked Kathleen what the man looked like, she said he ‘was no taller than I am, possibly, he could have been a few inches taller, maybe 6’ but absolutely not taller than 6’… I don’t remember thinking that he was a lot shorter than I, nor a lot taller. I would say he was probably around my height. He had brown, light brown kind of shaggy hair, no real style, no real cut, cut kind of long and shaggy. He was thin and his face is a blur to me. I don’t remember his features at all. I don’t really recall if he had a mustache or not. I picture him in my mind both ways, one with and without one. The same thing about glasses: in one thought in my mind, I picture him with wire rims, and another I don’t. I don’t really know. He was dressed kind of sloppily, not real grubby, but nothing outstanding.’

When asked about the condition of his arms, D’Olivo said ‘his left arm was in a sling, no cast, no plaster of Paris cast I know that, but it was in a sling. His right arm had like a hard brace, or finger brace.’ … ‘I think it was metal. He had bandages wrapped around it. It was supporting his fingers. I’m not sure if his arm that was in a sling was wrapped, but I think that it was. He told me that he had hurt it skiing. He’d run into a tree or something and bent his fingers back, and dislocated his shoulder (or did something to his shoulder).’ She clarified that he did not tell her where the accident happened.

When Keppel asked her if the man ever showed signs of being in any sort of pain from his injury, D’Olivo said that ‘he may have mentioned that he was in pain, maybe once, but he didn’t make a real big deal out of it; it was just so obvious that he was helpless that he’d have to be in pain, that’s the way it appeared to me, anyway. He told me that he’d been in an accident (ski) and this is what happened, and the way he was bandaged up it all made sense, the sling on his arms and shoulder, etc.’

Additionally, she recalled that he was soft spoken, and was dressed ‘sloppily, not real grubby, but nothing outstanding,’ and may have worn jeans with a wrinkled shirt, with ‘the tail hanging out.’ When asked if she recalled what the man was wearing, and if he had on for instance a short or jacket she said, ‘it seems to me that he had a shirt on, like a sport shirt, it was very sloppy or wrinkly looking. It seems to me he had a shirt-tail hanging out. I mean, intentionally hanging out, wearing it on the other side of his pants. I don’t remember what type of pants he had on, just all-around kind of grubby, like jeans or something like that.’

Kathy said that the strangers car was parked on 10th Street, and as they got closer to it she noticed that it was a ‘no parking’ area on the outskirts of campus and was in a secluded, dimly lit area that was ‘not well travelled.’ During their walk, D’Olivo said he talked about how much pain he w as in, and as they went under the railroad trestle, she said that she could vaguely make out the shape of a VW Bug in the distance that was parked to the right of the large trestle: ‘it was a dark road. There were no streetlights on that road … but it wasn’t completely black.’ This would make sense, as the only light available to them was from the library and an adjacent building, both of which were a fair distance away.’

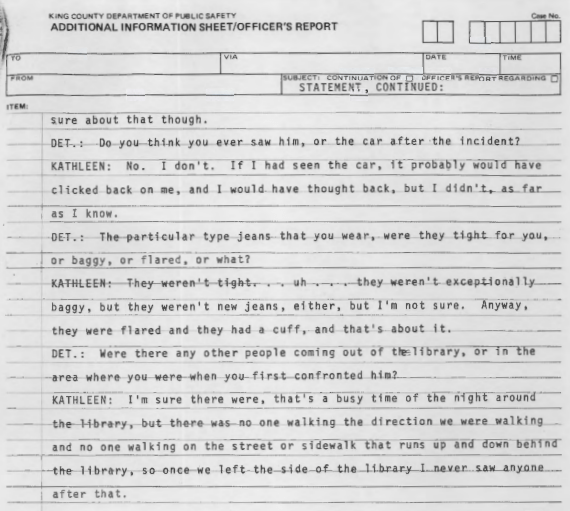

When they got to the car, Kathy said that she ‘set the pack down, well first of all, he went to unlock the door on the passenger side, which is the inside… I mean, the car was parked right next to a log and there was room between it for a person, and he went to unlock the car on the passengers side, and I set down the package (the pack) that I had been carrying and leaned it against the log and I think I said goodbye… anyways, my thought was well, I had done my deed and I was going to leave, and then he was supposedly unlocking the car and he dropped the key; then he felt for the key with his right hand and he couldn’t find it apparently and he said, ‘do you think you could find it for me because I can’t feel with this thing on my hand (meaning the brace on his right hand. I was cautious this time, I mean, even while we were walking I thought well, I’m not going to let him get behind me, I’m going to keep an eye on him, I’ve got these heavy books and I can use them. But I didn’t want to bend over in front of him so I said, lets step back and see if we can see the reflection in the light, so we stepped behind the car, kind of behind the car to the side, and I squatted down and luckily I did see the reflection of the key in the light so I picked up the key and dropped them in his hand and I said goodbye and good luck, or something with your arms, or something to that effect, and that was the end of the conversation.’ She also said that the lack of light made the VW appear shiny and brown in color and that it appeared to be in good shape (which we know isn’t exactly true), and as far as Kathy could remember it did not have a ski rack on top of it.

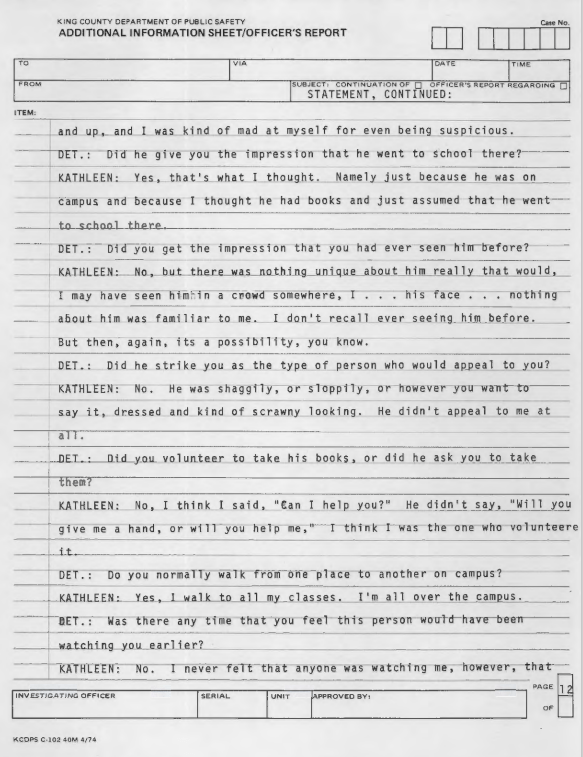

When Detective Keppel asked D’Olivo if she thought the man’s intentions were sincere, she told him, ‘yes, I did… Ya, and I thought he was just going into the library, it was just a short distance and her really did need help and I thought I could help him.’ She also said that nothing seemed unusual about his car when she was asked, and about it said: ‘it looked, just very normal, like any VW on the street.’ … ‘All I really noticed was that it was a nice VW, it was in good shape. And it was shiny.’

When Detective Keppel asked Kathy if she happened to notice if the VW’s front seat was missing on the passengers side, she replied that she ‘left before he opened the car. I didn’t notice it and I was right alongside the car on the passengers side. I think I would have if there had been a seat missing, but I can’t be certain on that, but it seemed all intact to me and in good shape.’ Like Jane Curtis, she said that the car had no particular odor associated with it, like cigarettes or marijuana smoke.

When asked if the man seemed disappointed when she left him, Kathleen said, ‘no, not at all. That’s why I wasn’t suspicious, because it was just a small thank you for helping me, was the attitude that I picked up anyway, and uh… he didn’t seem nervous that I was leaving. He didn’t say, ‘hey, do you need a ride home’ or ‘how ’bout a ride? or get in the car,’ or anything like that. So I still felt that it was on the up and up, and I was kind of mad at myself for even being suspicious.’ When asked if she remembered seeing him around campus (before and after the incident), she said: ‘there was nothing unique about him really that would. I may have seen him in a crows somewhere… I… his face… nothing about him was familiar to me. I don’t recall ever seeing him before.’ Kathleen also said that he was not ‘very appealing’ to her, and ‘he was shaggily, or sloppily, or however you want to say it, dressed and kind of scrawny looking. He didn’t appeal to me at all.’ Ms. D’Olivo further clarified that the stranger was not clean cut nor a hippy, but was ‘kind of weird looking, and when asked if he appeared to be athletic, she replied, ‘no, not at all. No, he just… he didn’t fit the stereotype in my mind of an athlete, or even a skier.’

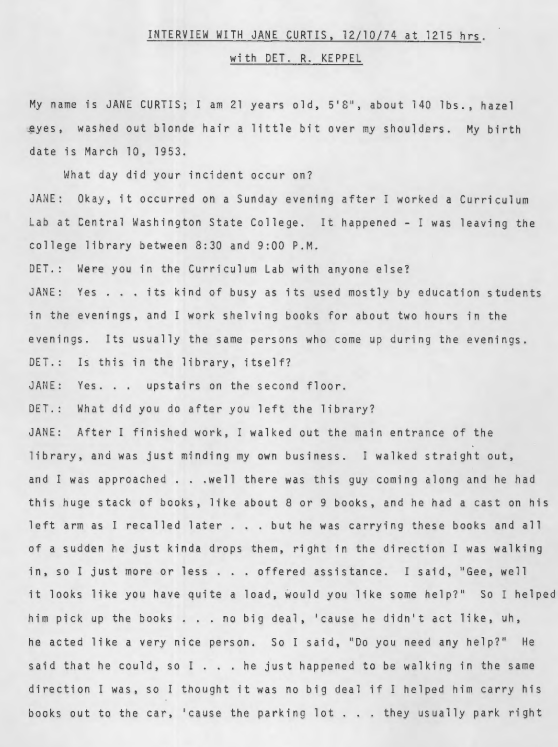

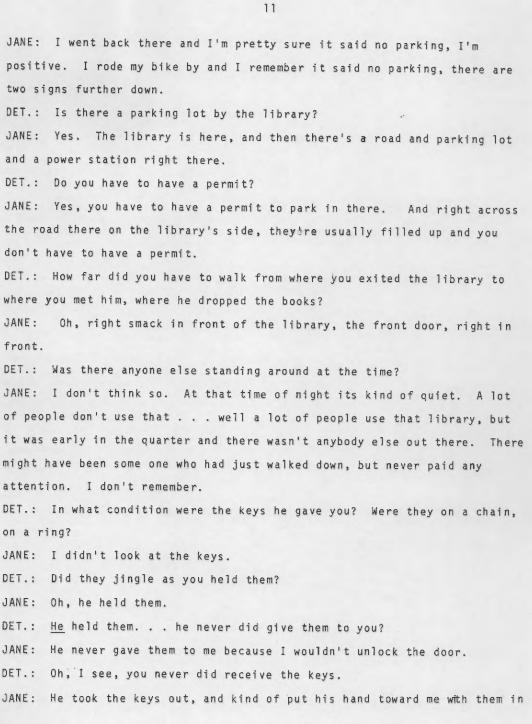

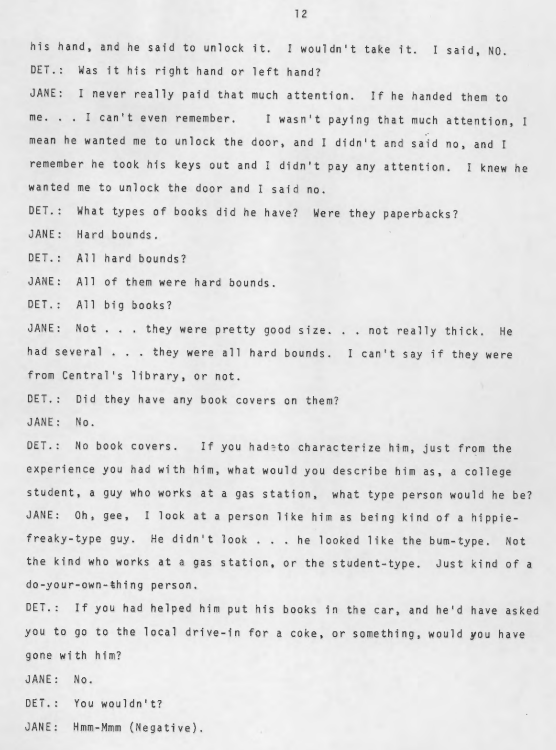

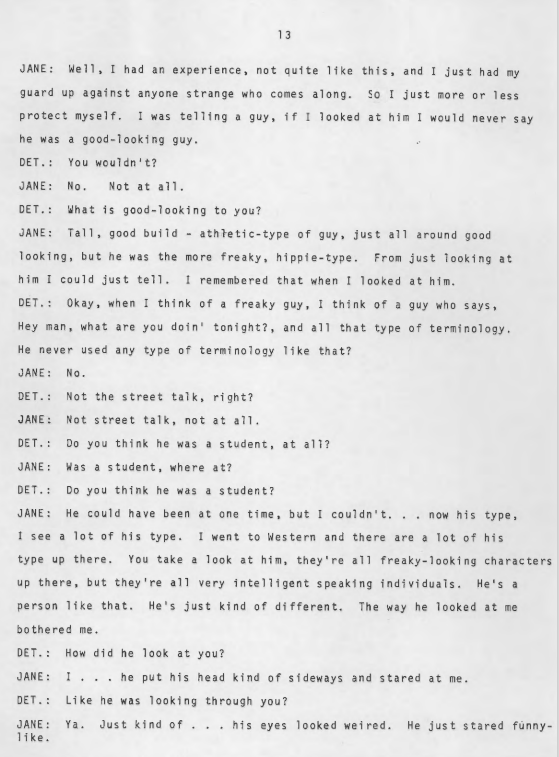

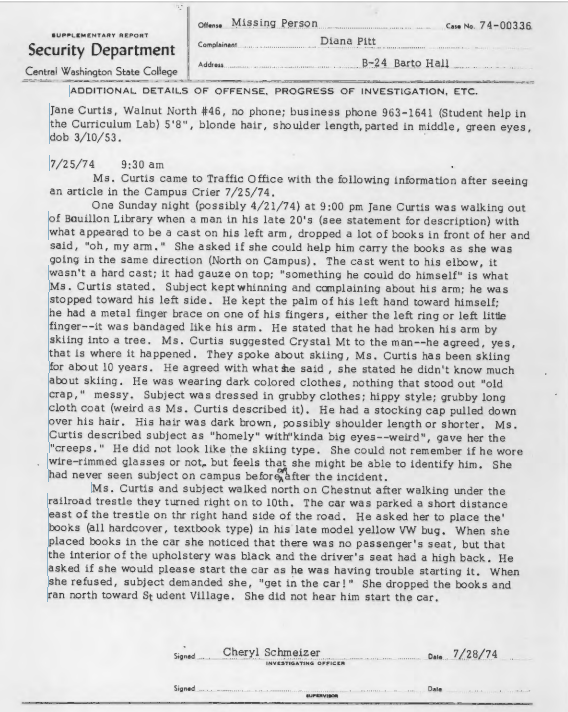

Another young woman that may have had an encounter with Ted Bundy on Central Washington University’s campus is Jane Marie Curtis: at first I believed Jane’s encounter took place earlier in the same evening that Sue Rancourt was abducted (because that’s the date that was given in everything I’ve read about her), but after reading her interview with Detective Keppel I learned it actually took place on a Sunday evening, most likely on April 14, 1974 or April 21, 1974. Like Kathleen, Curtis had been spending time at the Curriculum Lab at CWU and ‘ran into’ Bundy as she was walking out of the main entrance at the Bouillon Library. She said he used the same ruse that he did with D’Olivo: he had been in a skiing accident and needed help carrying some heavy books to his car, as his arm was in a (poorly made) sling. Like Kathy, Curtis was lucky and managed to leave Bundy alive.

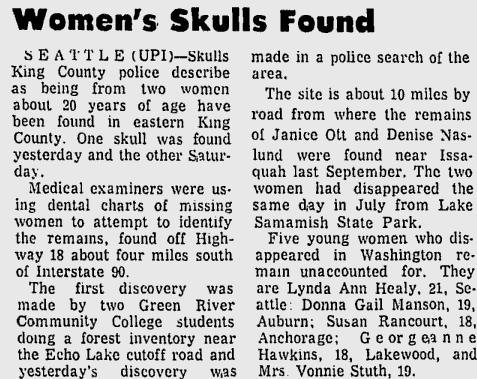

Kathy D’Olivo and Jane Curtis were both able to escape with their lives, but unfortunately Susan Rancourt was not so fortunate: later in the evening on April 17, 1974 around 10/10:30 PM Bundy stumbled upon the pretty young Biology major as she left a meeting about becoming an RA the following school year. After the meeting she had plans to see a German film with a friend but she never made it, and it didn’t take long for her friends and family to become worried, and by 3:00 AM her roommate Diana Pitt called the dorm manager, saying: ‘I got worried she wasn’t back.’ Parts of Rancourt’s skeleton were discovered in Taylor Mountain in March 1975 after two forestry students uncovered multiple sets of human remains; after combing the area, the King County Sheriff’s Department discovered four skulls in total as well as an assortment of other human bones.

In addition to Sue Rancourt, forensic experts were able to determine that the remains belonged to University of Washington coed Lynda Ann Healy, University of Oregon student Roberta Parks, and twenty-two-year-old loner Brenda Carol Ball. Later in the same day that Sue’s skull was identified, the King County ME took X-rays of her skull and mailed them special delivery to her dentist in Alaska, who confirmed it was her. According to CWU’s Police Chief Al Pickles: ‘there were several points of identification that made us almost sure the skull was Rancourt’s. This switches the case from a missing person to a homicide.’

Elizabeth D’Olivo passed away at the age of sixty-eight on March 15, 1999 in Mexico. According to her obituary, Betty was a member of St. Charles Borromeo Church and her life revolved around her friends and family, and she especially loved her four grandchildren. Kathy’s father Rinaldo passed away at the age of eighty on November 22, 2008 in their winter home in San Carlos, Mexico. According to his obit, he continued working in his family’s fireworks company until his time of his death. Kathy’s brother Ron died at the age of fifty-four on March 10, 2011 after a prolonged battle with lung disease. Douglas D’Olivo is currently a seventy-one-year-old resident of University Place, WA. Kathleen and David are still married and reside in University Place, WA; they have two grown daughters together: Amy and Emily.

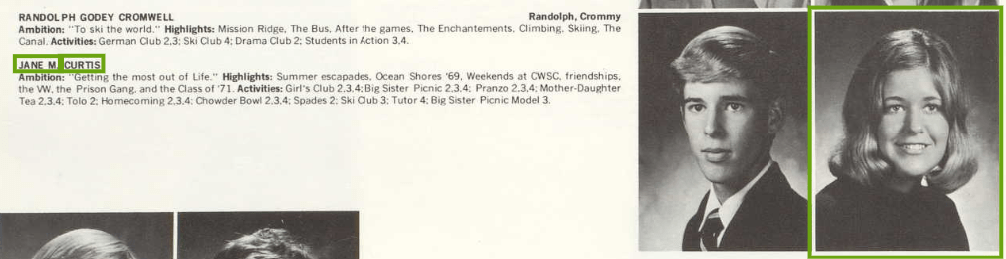

Jane Marie Curtis was born in Washington state in 1953, and grew up in Edmonds; she graduated from Bellevue High School in 1971 and during her time there she participated in multiple clubs and organizations, including ‘Girls Club,’ the Big Sister Picnic, Mother-Daughter Tea, Homecoming Committee, the Chowder Bowl, Spades, and Ski Club. After Curtis graduated from high school she enrolled at Central Washington University, and while there she was a sorority sister and in April 1974 she lived in the dormitories on campus, specifically at ‘Walnut North #46.’

At the time of her encounter with Bundy, Jane was a twenty-one-year-old student at CWU and stood at 5’6″ tall (one report listed her height as 5’8”) and weighed 140 pounds; she had hazel eyes (although one source said they were green), and had ‘washed out blonde hair’ that she wore at her shoulders.

Most websites and articles about Jane’s run-in with Ted claim that she encountered him earlier in the evening on April 17, 1974 (which is earlier in the evening before Sue Rancourt was abducted), but after reading her interview with Detective Robert Keppel of the King County Sheriff’s Department, I learned that it actually took place on a Sunday, (either on April 14, 1974 or April 21,1974) after she left her job at the Curriculum Lab at the James E. Brooks Library at campus, sometime between 8:30 and 9 PM. She worked ten hours a week on the second floor, and upon leaving her POE she walked out of the front door, and shortly after was approached by a young man that was ‘carrying a huge stack of books, like about eight or nine books, and he had a cast* on his left arm as I recalled earlier. But he was carrying these books and all of a sudden he just kinda drops them, right in the direction I was walking in, so I just more or less… offered assistance. I said, ‘gee, well it looks like you have quite a load, would you like some help?’ so I helped him pick up the book, no big deal, cause he didn’t act like, uh, he acted like a very nice person. So I said, ‘do you need any help?’ He said that he could, so I…’ Curtis clarified that he did carry a few of his books, but she carried the majority of them and they were all hardcover. Jane also said that she remembered the man was a bit ‘shorter than she was,’ because she happened to have on platform shoes that day that placed her at around 5’9″. *One sources says that Bundy was using crutches when he approached Curtis, but she never mentioned it in her interviews with LE.

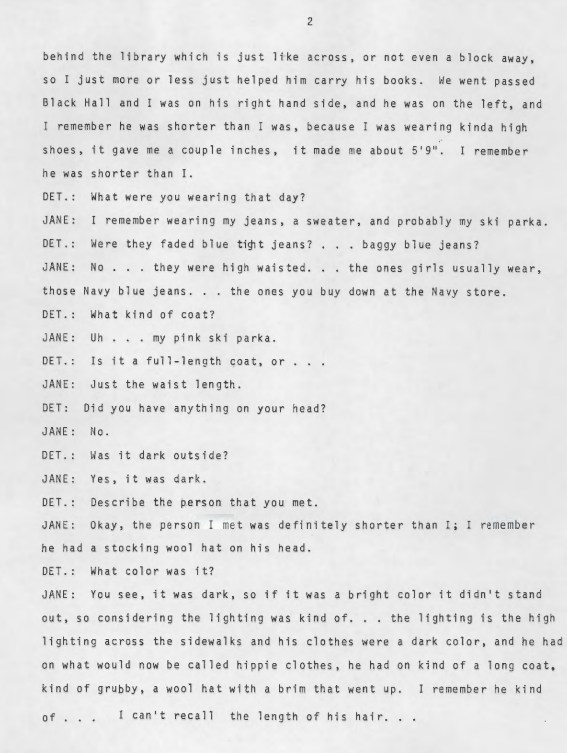

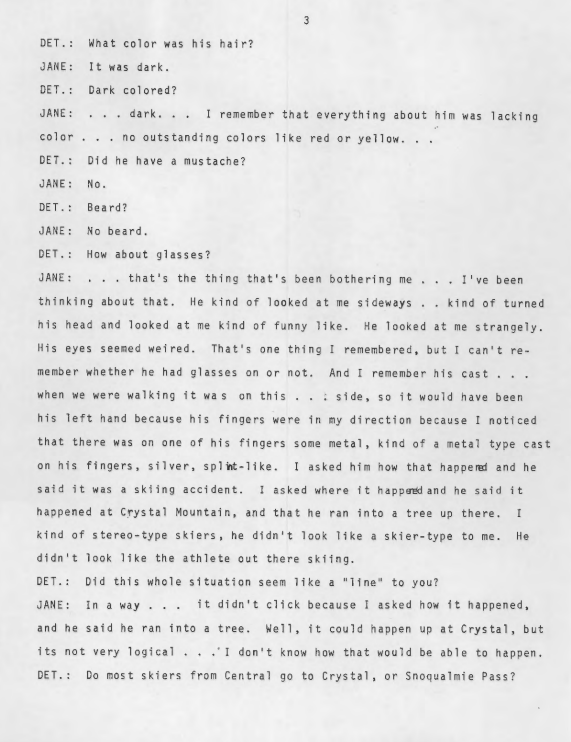

Curtis said the man was wearing a dark colored stocking hat that ‘went up’ on his head and that his ‘hippie clothes’ were on the blackish side and he also had on a long, ‘grubby’ coat. She also stated that he had dark hair and that ‘everything about him was lacking color:’ ‘no outstanding colors like red or yellow.’ She said where she was certain he had no beard or mustache she wasn’t completely certain if he wore glasses or not, as he looked at her ‘strangely,’ and his eyes looked: ‘weird. That’s one thing I remembered, but I can’t remember whether he had glasses on or not.’ In regard to what hand the cast was on, she said it would have been his left hand because when they were walking it was on (…) side, so it would have been his left hand because his fingers were in my direction because I noticed that there was on one of his fingers some metal, kind of a metal type cast on his fingers, silver, splint-like.‘ When Curtis asked the stranger how the injury happened, he said it was from a skiing injury but was reluctant to say much else on it, and after she suggested ‘Crystal Mountain’ as where the accident took place he immediately responded, ‘yes, that’s where it happened, and he elaborated that he ‘ran into a tree up there.’ She commented that he didn’t strike her as the skiing type, and that he didn’t appear to her to be much of an athlete; she also said she thought the scenario could have possibly happened, but she felt it was highly unlikely.

When Detective Keppel asked Jane if the man was skinny, she said no but that his ‘coat was big, kinda bulky looking, slouched over.’ She also said he didn’t appear to be in any pain from his injury and his arm only seemed to hurt when she started to allude that she didn’t want to further help him, or get in his car: ‘the only thing, only the times when he needed help, like when I said I was leaving, when I approached the car, then he wanted me to get in, then all of a sudden he started, like, ‘ohhhh my arm,’ he went on about his arm hurting him, and he said don’t forget I have a broken arm, you feel sorry for me… get in…’

When Keppel asked Curtis what the man’s sling looked like, she said that ‘it looked like, when I was at Western I was in a cast for several months, and it looked like, it wasn’t hard… not the plaster. It looked like the wrapping of gauze-type.‘ … ‘It was white, with white wrapping. It was completely around his fingers, across here, around this thumb and up his arm, but he had his coat up. The coat was over it, but only part way up so you could see it. Then he had that metal thing on his finger, it looks like maybe it was something you could do yourself.’ Curtis told the detective that it was unusual to her that he would have a broken arm and not have a real cast on it: ‘because I had the gauze on before the swelling went down, then they put a hard cast on me. It looked like something that anybody could do if they wanted to. I just sorta glanced at it, but it didn’t look like a professional job. That little metal thing over his finger looked like it was just taped on.’

As they approached the car, Bundy told her to open it up, and after she replied ‘what?’ he handed her his car keys, to which she refused and told him no. When they arrived at the VW, the car was locked, and after he unlocked and opened the door, she peered inside of it and immediately noticed that there was no passenger seat: ‘it was simply gone, with nothing in its place.’ She said the man ‘wasn’t saying anything, and after he opened the door he said, ‘get in,’ to which she said ‘what,’ then he quickly said, ‘ohhhh, could you get in and start the car for me?’ I said, I can’t.’ So he was wincing at the time about his arm.’ When pressed about what was inside of the car, Curtis said there was a ‘square box in the back, way in the back in a cubby hole behind the back seat. There was something back there, but there was nothing unusual that struck me except the whole passengers seat was gone.’ Jane said that the car was for the most part non-descript and had no CWU stickers on it.

Curtis told Detective Keppel that the man never touched her and he ‘probably more or less just wanted me to feel sorry, and get in, and I just dropped his books after he told me that and I took off.’ When she turned around and left him she didn’t run, and only briskly walked away and he didn’t chase or come after her and she just went back to her on-campus apartment; she also said that as she was running away from him she never heard him start his car.

Curtis said the car was yellow in color and didn’t seem to have any particular smell, like he had been smoking in it, andthat it had been parked in a ‘no parking area,’ because it was in an spot that ‘went around a curve, and right in there there’s a road and it has the block-wooden blocks, and there’s a parking lot area for the tickers for the lower dorm, then right around the corner there’s kind of a high grass and ditch.’

At the end of the interview with Detective Keppel, Curtis said that the man told her to: ‘start the car for me, I remembered that. First of all, he told me to get in, I said what, then he went through his little pain bit, and said get in and start the car for me because I can’t. He said because of his arm he couldn’t start it. He wanted me to start it for him.’ She also clarified that the ignition on the VW was on the left hand side.

At around 8 PM on April 17, 1974 (which was about two hours before Sue Rancourt went missing) CWU student named Kathleen D’Olovio reported to police that she was approached by a man using the same ruse as Jane Curtis: he had his arm in a sling and was looking for some help carrying some books to his car. D’Oloviosaidwhen they reached his Volkswagen, the man dropped his keys and asked her for some help finding them, but her suspicions were raised after she noticed the cast on his arm didn’t look as if a medical professional put it on. Wisely, instead of bending over to look for the keys she suggested they look for them using the reflection from a car’s lights: once she found them she immediately snatched them up, tossed them at Bundy then quickly got out of there, an act that most likely saved her life. This most likely threw Ted off, as he was most likely hoping she would lean over so he would have had a good angle to bash her over the head from behind with a crowbar (or tire iron), and she was able to get away unharmed.

As we all know, after the failed abduction of both Jane Curtis and Kathleen D ‘Olivo Ted went on to find a victim in Sue Rancourt, who was last seen around 10 PM on April 17, 1974 leaving a meeting of ‘The Living Group Advisors’ at 9:30 PM in Munson Hall about possibly being an RA the following year (which would have helped her save in tuition costs).

* In November 2025 I received an email from Jane asking me to take the post down, and where I did spend a lot of time thinking about what to do I ultimately decided to take all of the personal details out, but leave the Bundy related information.

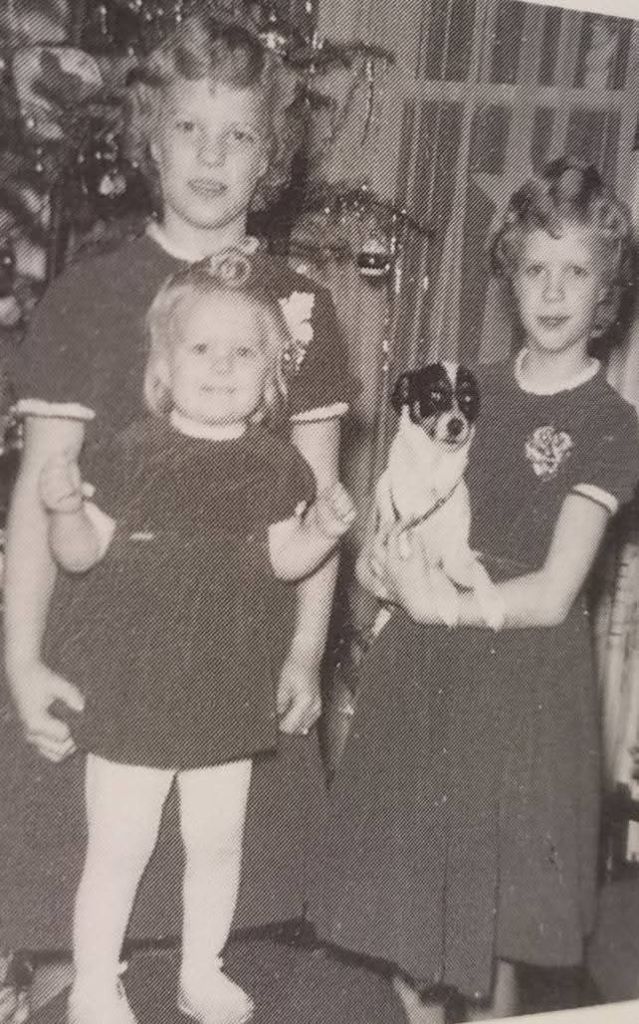

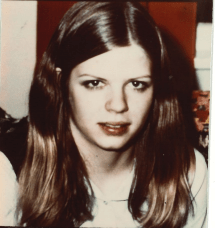

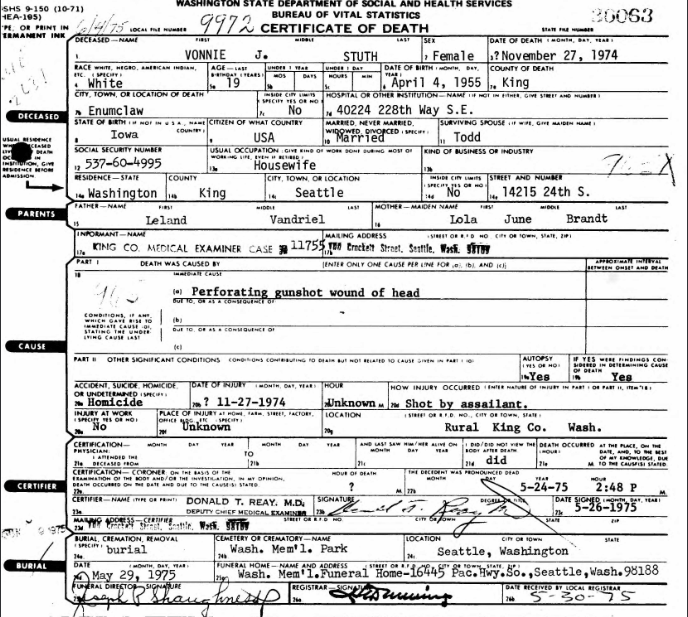

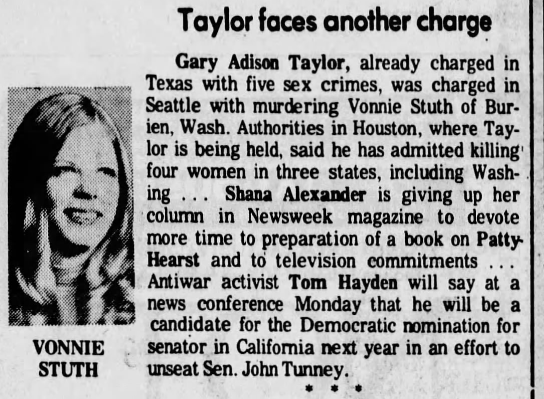

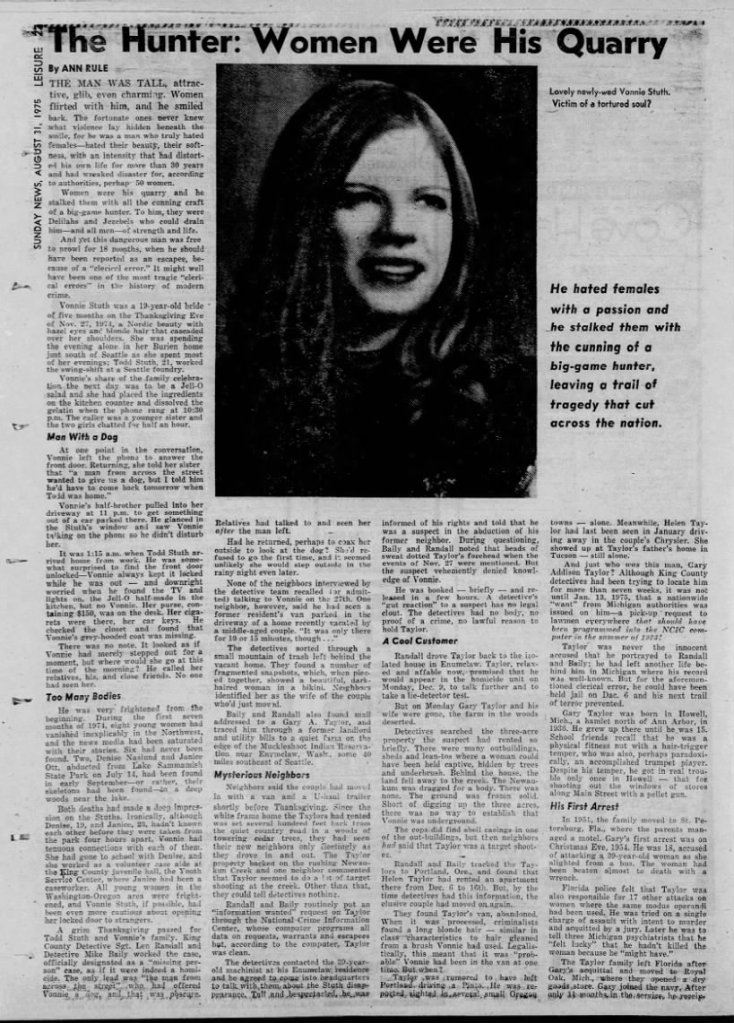

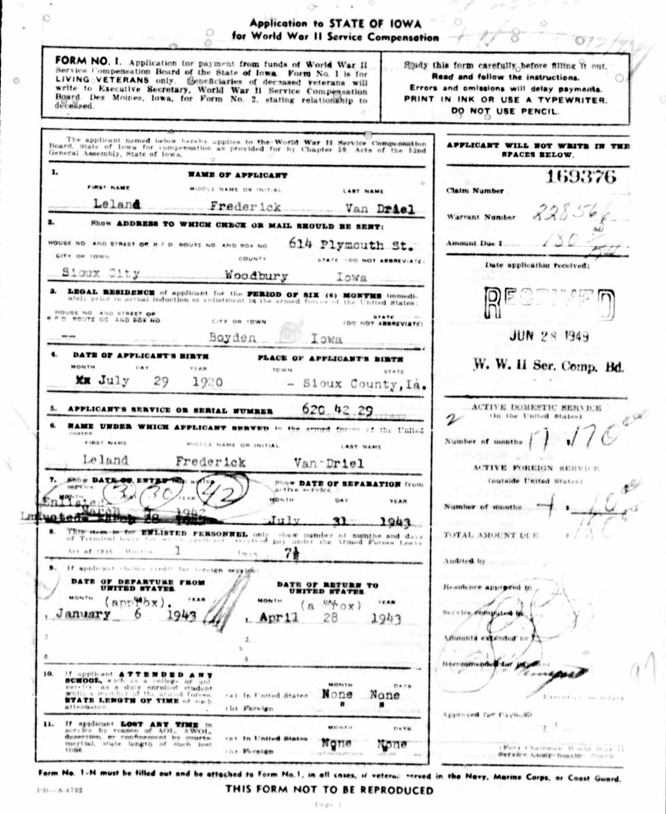

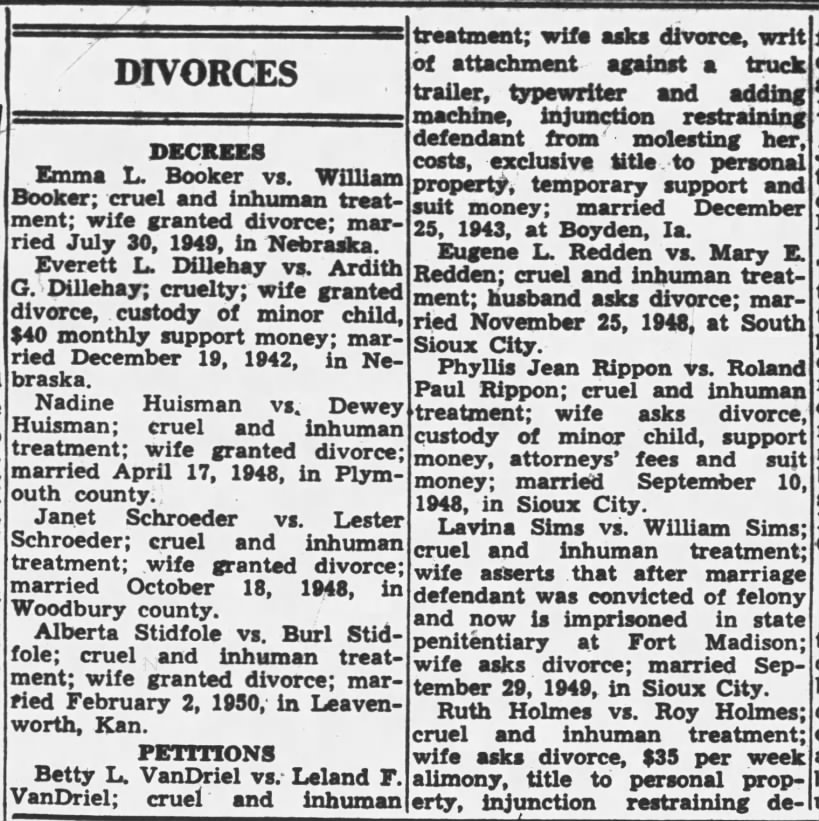

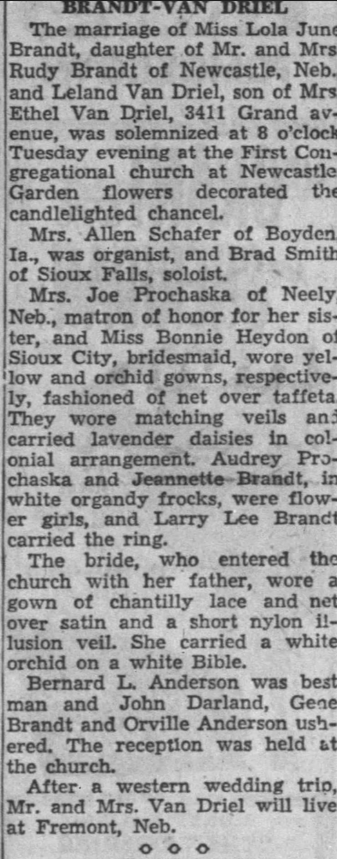

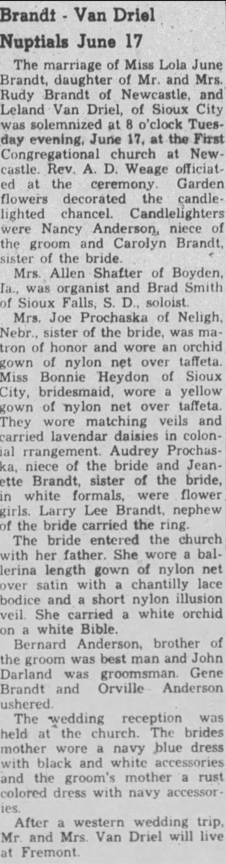

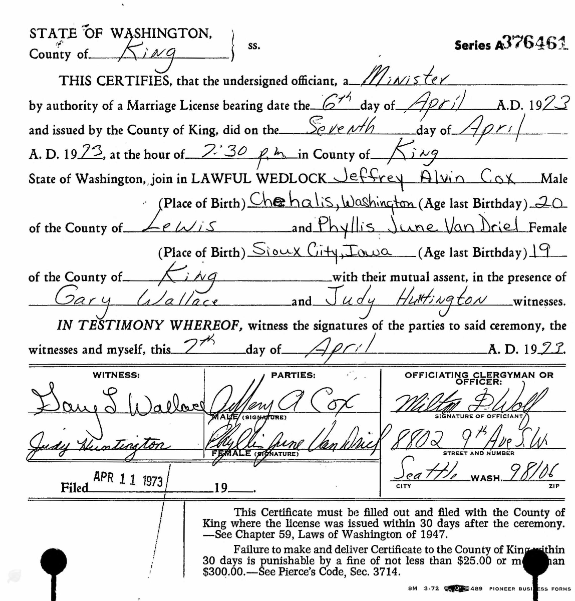

Vonnie Joyce Van Driel* was born on April 4, 1955 in Sioux City, Iowa to Leland and Lola (nee Brandt) Van Driel. Leland Fredrick Van Driel was born on July 29, 1920 in Sioux, Iowa, and Lola June Brandt was born on a farm in Nebraska on June 17, 1932. Leland was married once before Lola to a woman named Betty, and they divorced in May 1950 due to ‘cruel and inhumane treatment.’ The couple were married on June 17, 1952 and had four daughters together: Phyllis, Vonnie, Alicia, and Shirley. They relocated to Seattle when Leland got a job at Boeing, and Mrs. Van Driel was a stay at home wife and mother, and loved caring for her family. She filed for divorce in 1970, which was granted on June 6 and got married for a second time to Kenneth J. Linstad on June 19, 1972. * I have seen the family’s last name as VanDriel as well as Van Driel.

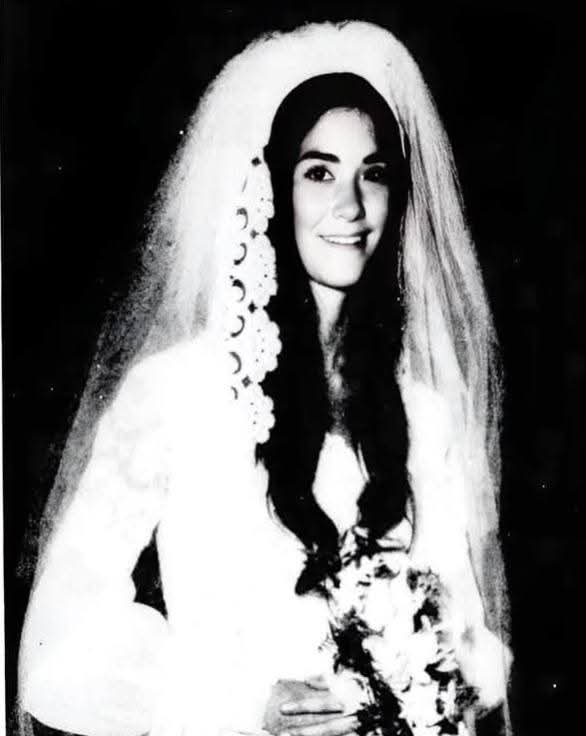

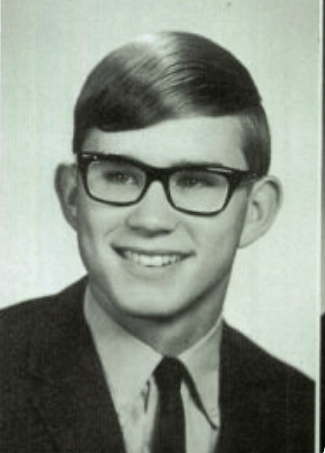

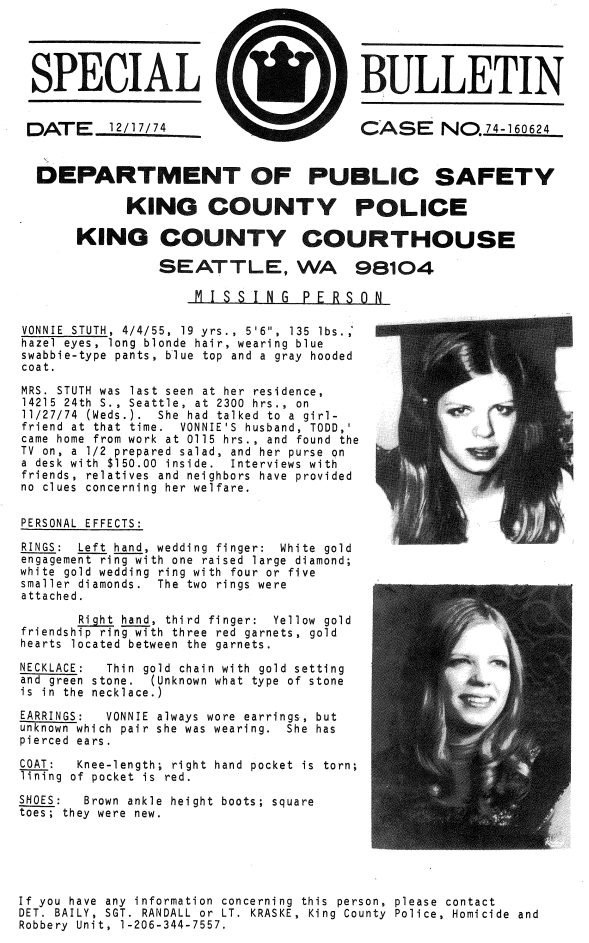

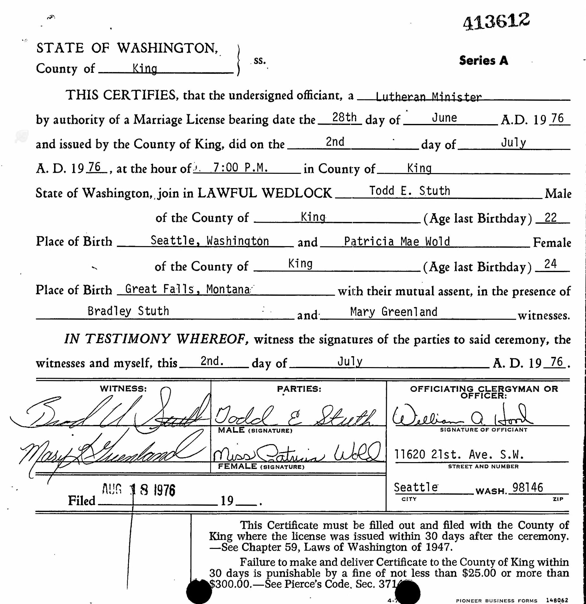

Vonnie graduated from Sealth High School in 1973, and married Todd Stuth on May 4, 1974; according to her marriage certificate, she was a housewife and volunteered at the Youth Service Center in Seattle. The newlyweds moved into a basement apartment located at 14215 24th Street South in Burien, which was roughly twenty miles away from the University of Washington. Todd Elliott Stuth was born on August 10, 1953 in Kent, WA, and graduated from Lincoln High School in 1971. At the time of his wife’s death he was a criminal law major at Highland Community College in Des Moines (which is the same school Brenda Ball attended before she dropped out), and worked the swing shift at Pacific Car & Foundry.

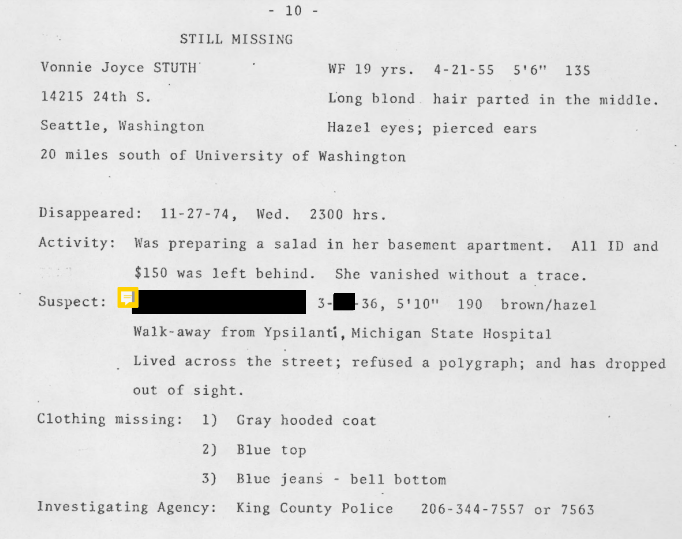

Late in the day on November 27, 1974 Vonnie kissed her husband goodbye in their Burien apartment and sent him off to work: twenty-one year old Todd began his day in the late afternoon and got home after midnight, and she had gotten used to spending her evenings alone. It was the evening before Thanksgiving, and the beautiful young newlywed told her family that her contribution that year was going to be a Jell-O salad, and she had just placed the ingredients on the kitchen counter and dissolved the package of gelatin when her thirteen year old sister Alicia called her at around 10:20/10:25 PM, and the two chatted for roughly a half hour.

Alicia said at one point during their chat, her sister put the phone down to answer a knock at the front door, and when she came back she said that ‘a man from across the street wanted to give us a dog (as they were moving), but I told him he’d have to come back tomorrow when Todd was home.’ Around 11 PM Vonnie’s half-brother stopped over to get something out of one of the family cars parked in the driveway: after looking in the window he saw she was on the phone, and since he knew what he needed and where it was he didn’t bother her.

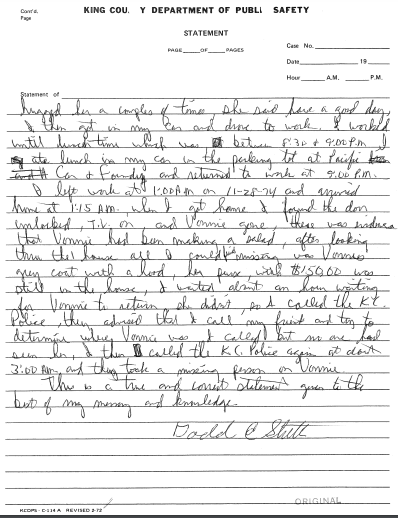

When Todd arrived home around 1:15 AM on November 28, 1974 he came home to an empty house: the front door was unlocked (which was unusual for his wife), the TV was on, and all of the ingredients for the Jello-O salad were left out on the kitchen counter. All of his wife’s belongings were present and accounted for, and her keys, drivers license, cigarettes, and $150 were found in her purse, which was left behind on the counter. Vonnie left no note, and missing from her wardrobe was a blue shirt, a pair of bell-bottoms, and her grey-hooded coat. Todd immediately started calling around to her family and friends, but they hadn’t heard from her; after an hour of waiting he called the King County Sheriff’s Department and tried to report her as missing, but was told by the dispatcher that he needed to wait the standard 48 hours until a missing person’s report could be filed.

The Van Driels/Stuth’s had a grim Thanksgiving with no news about Vonnie, and after the standard forty-eight hours passed Todd was finally able to file a report with the sheriff’s department. King County Detective Sergeant Len Randall and Detective Mike Baily almost immediately designated it as a ‘missing person’ case, and the only real lead they had to work with was ‘the man from across the street that had offered her a dog’ (and even that was vague).

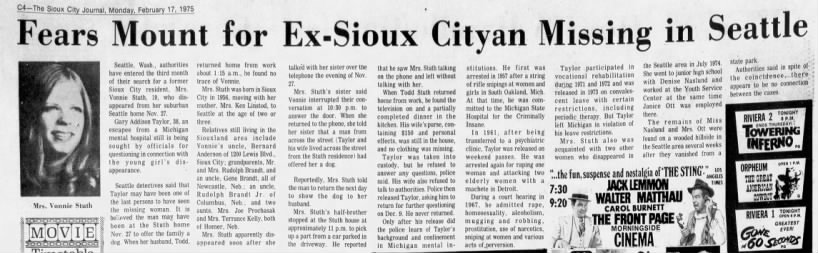

Ted Bundy: In the early part of the investigation Vonnie was thought to be a victim of the mysterious ‘Ted of the Northwest,’ and she was often included in his list of Washington state victims: in the first seven months of 1974, eight young women had vanished in and around the Seattle area, and the news had been filled with their stories. At the time Stuth went missing in November 1974 Ted was living in his first SLC apartment and was a full-time law student at the University of Utah; he was still in a relationship with Elizabeth Kloepfer and the two were trying the long distance thing (despite the fact that he was unfaithful to her on multiple occasions). He was in between jobs at the time, as he left the Department of Emergency Services in Olympia on August 28, 1974 and remained unemployed until June of the following year when he got a position as the night manager of Bailiff Hall at the University of Utah (he was fired the next month for showing up drunk).

Over time, detectives were unable to establish any connection between Stuth and Bundy, and her case helped to highlight systemic flaws in the missing-persons reporting system at the time. Strangely enough, Vonnie had ties to both of Ted’s victims that were taken from Lake Sammamish State Park on July 14, 1974: Denise Naslund was in the same graduating class as her at Sealth High School, and she worked as a volunteer case aide in the Youth Service Center at the King County Juvenile Hall, where Janice Ott had been a caseworker.

After canvassing the neighborhood, the detectives quickly learned that the man with the dog had already moved Enumclaw, which makes the situation even more unusual since he no longer lived in the area. None of the Stuth’s neighbors recalled talking to Vonnie on the evening of November 27th, but one of them told investigators that he had seen a former resident’s 1972 Dodge van parked in the driveway of the home they had once rented, but ‘it was only there for 10 or 15 minutes.’

The detectives searched the abandoned home, and went through a ‘small mountain’ of trash that had been left behind by the former tenants and found a large number of torn up pictures; when reassembled one of them was of a beautiful, dark haired woman dressed in a bikini that one of the neighbors identified as Helen, who was half of the couple that had just moved out. The investigating officers also found mail addressed to a man named ‘Gary A. Taylor,’ and they were able to trace him through a former landlord and utility bills to a quiet farm on the edge of the Muckleshoot Indian Reservation, close to Enumclaw.

The Taylors’ new neighbors said the couple had moved into the white frame house with a van and U-Haul trailer shortly before Thanksgiving; the property was located next to the Newaukun Creek and one neighbor commented that Gary seemed to do a lot of target shooting aimed at the water, but other than that they could tell detectives nothing. Officers Randall and Baily put in a few ‘information wanted’ requests on Gary A. Taylor through the National Crime Information Center (whose computer programs all data on requests, warrants and escapees), but he came back clean and with no warrants.

Investigators were brought to a farm in Burien that had been rented by the Taylor’s after receiving reports of ‘unusual mounds of dirt’ found on the property, and according to a King County detective, ‘the story that we were probing for grave sites was possibly a misinterpretation by the media. Searching out there was just a long shot, but we had to check it out. The two earth mounds turned out to be a buried garbage pit and a stump.’

After Detectives Baily and Randall tracked them down, the Taylor’s were brought in for questioning, but they refused to answer any questions, and Gary denied ever knowing Vonnie. The officers got him a public defender and he was booked on December 6, 1974 but was released after a few hours, as their ‘gut feeling’ to a suspect’s guilt had no legal clout, and they had no body, no proof of a crime, and no lawful reason to hold Taylor. He promised King County Sheriff’s that he would come in on Monday, December 9, 1974 for another conversation (and a polygraph), but he never showed up.

After the Taylor’s skipped town detectives searched their residence and the surrounding property: there were many outbuildings, sheds, and lean-to’s where they could have left a body that were all hidden by trees and underbrush. Directly behind the house, the land fell away to the Newaukum Creek, which was immediately dragged for a body but with no luck, and because it was the middle of winter the ground was frozen solid, and short of digging up the entire three acres of property, there was no way to establish that any remains had been buried there; additionally, they found shell casings in one of the buildings next to the main house.

Detectives Randall and Baily tracked the Taylors to Portland and learned that Helen had rented an apartment in her name from December 6 to the 16th, but by the time they learned this, the couple had already left and their van was found abandoned. When the vehicle was processed for evidence, forensic experts found a long blonde hair much like Vonnie Stuth’s, which meant it was ‘probable’ she had been in the vehicle at one point in time… but when? It was rumored that Gary Taylor was to have left Portland driving a Ford Pinto, and he was also sighted in several small Oregon towns (alone).

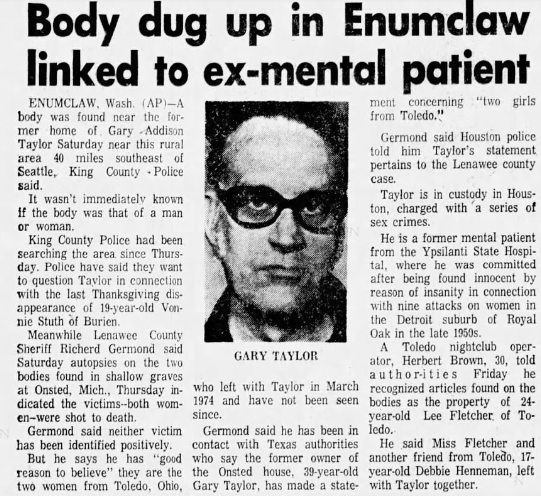

Gary Addison Taylor was born in Howell, Michigan in March 1936, and childhood friends recall that he was a physical fitness enthusiast that had a hair-trigger temper, but was also an accomplished trumpet player. Despite his outbursts, he had no real juvenile criminal record aside from one incident in Howell when he shot out of the windows of stores along Main Street with a pellet gun. In 1951 when Gary was fifteen the family moved to St. Petersburg, where his parents managed a motel.

While in Florida, he was responsible for ‘the bus stop phantom attacks,’ where he bludgeoned about a dozen women at bus stops during the late 1940’s and early 1950’s; his standard MO involved loitering around bus terminals at night and waiting for someone that was alone to walk by, which was when he pounced and would attack them with a hammer. His first arrest took place at the age of eighteen on Christmas Eve in 1954 after he nearly beat a 39-year-old woman to death with a wrench as she got off of a bus.

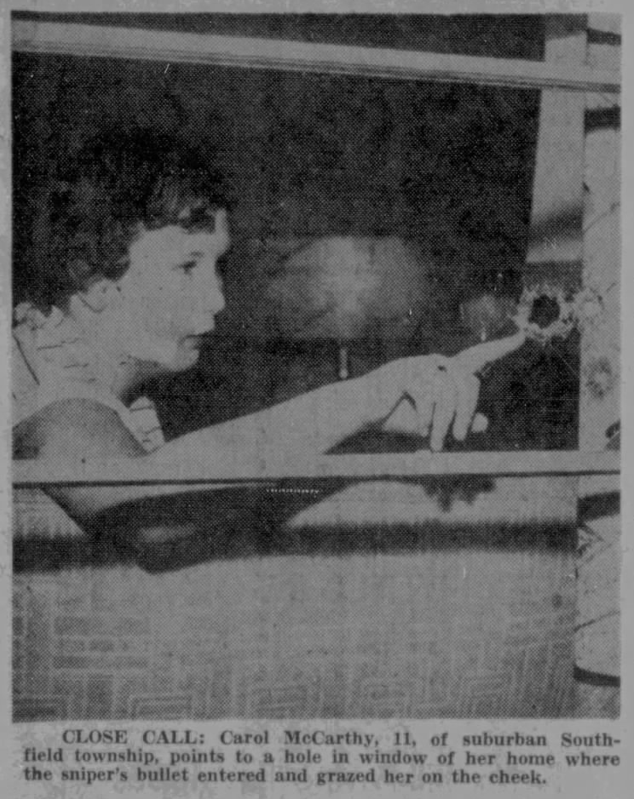

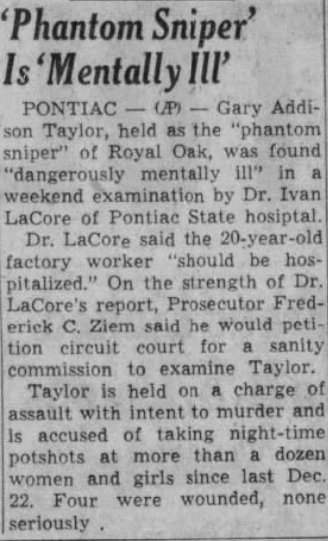

Despite investigators in the Sunshine State speculating that he was responsible for seventeen additional attacks on women where the same MO had been used, he was tried on a single assault charge with intent to kill but was acquitted by a jury; he later told three Michigan psychiatrists that he ‘felt lucky’ that he didn’t kill the woman, because he ‘might have.’ After their son’s acquittal the Taylors moved to Royal Oak, Michigan in 1951, where they opened a dry goods store and Gary joined the Navy… but it wasn’t long before he fell back into his old habits and began shooting women on the streets after dark. He was dubbed the ‘Royal Oak Sniper’ and shot sixteen women, but thankfully none of his victims were fatally wounded.

Two days before Christmas in 1956, Taylor shot and wounded a teenage girl in a drive-by attack in Royal Oak, and over the next few months he shot at several more females in a similar manner but thankfully missed every target. Several witnesses came forward and told police that the sniper was driving a two-toned black-and-white ’55 Chevrolet, and after they located the vehicle the suspect led them on a high-speed chase that ended in his arrest. Upon searching the car detectives discovered a .22 rifle, and Taylor couldn’t give them any particular explanation for his actions other than he wanted to shoot women and had these urges since he was a child, saying ‘it’s a sex drive compulsion.’

During Taylor’s trial, a psychiatrist testified that he was ‘unreasonably hostile toward women, and this makes it very possible that he might very well kill a person,’ and he was declared insane and was committed to Michigan’s Ionia State Hospital; three years later was transferred to the Lafayette Clinic in Detroit. While out on a work pass to attend a welding class, he talked his way into a woman’s home then raped and robbed her; the following year while out on another furlough he threatened a rooming-house manager and her daughter with an 18-inch butcher knife. He was not held responsible for either incident and was simply sent back to Ionia.

Even though he never stopped his violence against the opposite sex and had a self-proclaimed ‘compulsion to hurt women,’ Taylor was rated by prison staff as a ‘safe bet’ for out-patient treatment ‘as long as he reports in to receive medication.’ In 1970 he was transferred to an outpatient care facility after the director of the clinic determined that Taylor ‘was no longer mentally ill and would be dangerous only if he failed to take his medication,’ and drank alcohol.

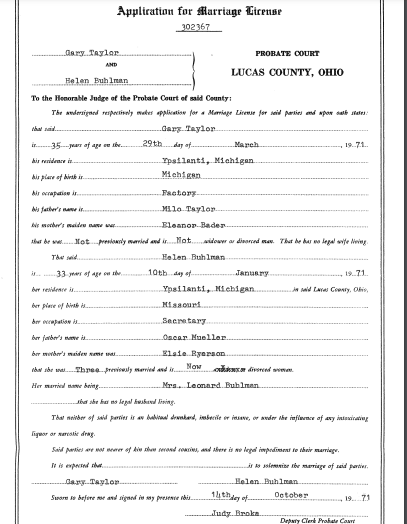

In 1972**, Taylor was released from the Michigan Center for Forensic Psychiatry in Ypsilanti thanks to a highly controversial state law: a person that had been acquitted of a crime by reason of insanity cannot be kept indefinitely in a mental institution and must be periodically declared mentally ill and deemed to be dangerous to himself or the community by a competent medical professional. Before his release, the center’s director Dr. Ames Robey diagnosed him with a character disorder (which is not a treatable mental illness), and felt that he was no longer dangerous as long as he was properly medicated and didn’t drink. Almost immediately after his release, Taylor married a secretary named Helen Buhlman, and the two moved first to Onsted, MI and later to the Seattle suburbs. **There may be some discrepancy as to exactly when he was released, as he was married on March 29, 1971 and another source said it was on November 3, 1973.

The state reported that in the two years after his release Taylor violated the conditions of his parole five times but was never recommitted by the Doctor, and after growing weary of reporting to treatment in late 1973 he completely stopped showing up altogether. When he failed to come in for scheduled check-in’s he wasn’t reported as an escaped mental patient for three months, and it wasn’t submitted into the national law enforcement communication system in Washington DC until January 13,1975. Plus, to make matters worse, when Michigan LE realized their mistake, the urgent bulletin they intended to release on November 6, 1974 never was and it slipped through the cracks.

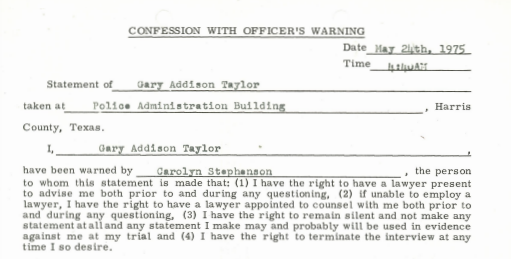

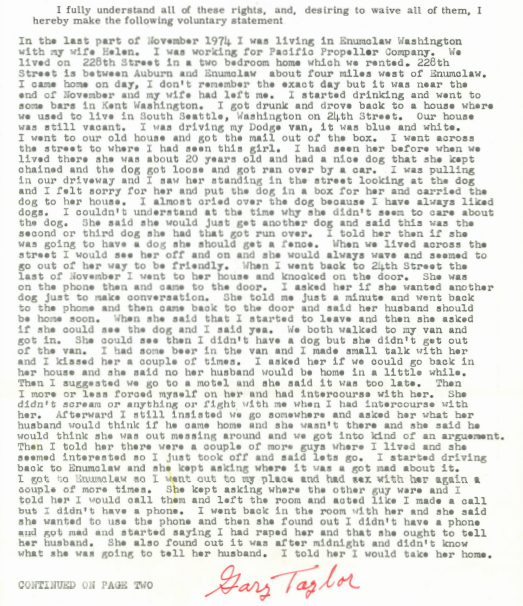

In December 1974 after separating from his wife, Taylor settled down in Houston, and Helen Taylor was last seen in January 1975 driving the couple’s Chrysler when she showed up at her FIL’s home in Tucson by herself. On May 20, 1975 Gary Addison Taylor was arrested in Houston for three counts of aggravated sexual abuse, one count of attempted aggravated rape, the rape of a 16-year-old pregnant girl, and the murder of a 21-year-old go-go dancer.

Discovery: According to an article published in The Times-Union on May 23, 1975, when news of her ex-husband’s arrest reached Helen (by that time she was in San Diego), she called Texas LE and told them that Gary had buried four bodies (three women and one man) underneath their bedroom window in a home they rented for three months in Michigan.

On May 18, 1975 the bodies of Vonnie Stuth and twenty-one year old Houston native Susan Jackson were found by detectives in a shallow grave along Neuwaukum Creek, roughly four to five miles northwest of Enumclaw; Stuth was ID’ed through dental records, and was still wearing the jeans, boots, and gray coat that were missing from her home the evening she disappeared. According to the King County ME, her exact cause of death is listed as a ‘perforating gunshot wound of the head,’ and detectives said she had been shot twice with a 9 mm pistol most likely during a desperate attempt to flee. They also said that due to the advanced level of decomposition it was impossible to tell if she had been sexually assaulted. Detectives said Jackson was last seen alive four days prior to the discovery leaving a Houston bar with Taylor, and her body had been bound with a dog leash and stuffed into a plastic garbage bag.

Tipped off by the Texas detectives, four days after the discovery of Stuth and Jackson investigators in Onsted discovered the remains of twenty-five year old Lee Fletcher and twenty-three year old Deborah Heneman from Toledo, wrapped in plastic bags, buried exactly where Helen said they were. After their discovery the remains were sent to the state police laboratory for analysis and autopsies were performed. Retired Sheriff Richard L. Germond said one of the victims was tied up with a piece of rope and the other had been bound with an electrical cord.

After his apprehension Taylor confessed to four murders (including Vonnie Stuth), however detectives were certain he wouldn’t have told them about any new women that they hadn’t already connected him to, meaning the actual number of his victims is unknown. After he admitted to killing Stuth, Taylor claimed that the detectives in Houston had beaten him into confessing and that there was no attorney present, which made the Texas and Michigan cases problematic. In an article published by The Daily News on August 31, 1975, Taylor was briefly a suspect in the death of Caryn Campbell (who wasn’t physically in Michigan when she disappeared but was from the state) and Julie Cunningham, who were both eventually tied to Ted Bundy. Further investigation cleared him of six additional murders in Washington state.

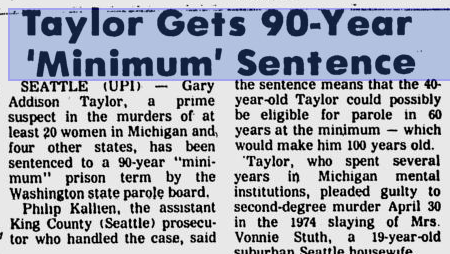

After his confession in Texas Taylor was extradited to Washington, where he was charged with first degree murder for the murder of Vonnie Stuth. On April 30, 1978 he pled guilty to second degree murder after an agreement was reached that both Texas and Michigan would not prosecute him for his crimes and he was sentenced to a ninety-year ‘minimum’ prison term by the Washington state parole board. Years after the conviction one of Vonnie’s sisters provided a victim impact statement to the Indeterminate Sentence Review Board, and Taylor’s parole was denied; his next parole date was set in 2035 when he will be 100 years old.

Todd Stuth: According to an article published in The Tri-City Herald on January 23, 1976, Vonnie’s widower Todd sued Gary Taylor’s former Psychiatrist Dr. Ames Robey for $2.5 million, as he was technically the one responsible for Taylor and he escaped under his watch. The former director of Michigan’s Center for Forensic Psychiatry, after the murders came to light Dr. Robey was suspended from his position and was eventually fired by the Michigan Department of Health after an inquiry into why his patient was free at the time of Stuth’s murder. In regard to the court case, Dr. Robey said in an interview: ‘I knew it was going to come.’

VSS/Victim Support Services: Lola ran a day care center out of her home and lived two blocks away from a woman named Linda Barker-Lowrance, and the two met when Linda needed someone to watch her kids when she went to PTA meetings. While waiting for answers as to what had happened to Vonnie, one evening when Linda arrived to pick up her children she said, ‘I am sorry my house is a mess but my daughter is missing.’ … ‘I wonder what the other mothers are doing?’

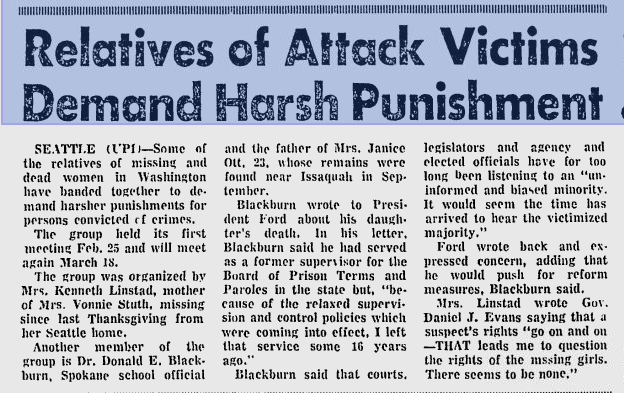

Despite over a fifteen year age gap between the two (and the fact that they hadn’t known each other for very long), Barker-Lowrance immediately responded, ‘let’s find out.’ The two women reached out to a Seattle-based newspaper reporter, who was able to give them phone numbers and addresses of several other families that had missing or murdered daughters and on February 25, 1975 thirteen families gathered in the social hall of a Catholic church in White Center. The group, officially dubbed ‘the Families and Friends of Violent Crime Victims***’ became one of the first victim advocacy groups in the US. *** It is now simply VSS.

Also a member of the group was Dr. Donald Blackburn, father of Bundy’s Lake Sammamish victim, Janice Ott. In a letter he wrote to President Ford about his daughter, Dr. Blackburn said that he had previously worked as a supervisor for the Board of Prison Terms and Paroles in Washington state, but ‘because of the relaxed supervision and control policies which were coming into effect, I left that service some sixteen years ago.’ President Ford wrote back saying he expressed concern about his daughter’s death and that he would try his hardest to push for reform.

Mrs. Linstad wrote to Bundy buddy Governor Daniel J. Evans in regards to the rights of a murder suspect, saying they ‘go on and on, that leads me to question the rights of the missing girls. There seems to be none.’ Lola’s baby now operates out of a two-story house on Colby Avenue and is staffed by eight full-time employees (including mental health professionals), and volunteers help to operate the crisis line after hours.

Mr. Van Driel died at the age of sixty-five on July 29, 1985 in Seattle, and Vonnie’s mother Lola died on October 1, 2024 in Sweet Home, Oregon. According to her obituary, at the age of eighteen she enrolled in secretarial college and after she got married and started her family they packed up and relocated to Seattle. She did a lot of fund raising for an organization called ‘The Healing Garden’ at Samaritan Hospital in Lebanon, Oregon and volunteered with a local soup kitchen and FISH food distribution pantry. She also taught Sunday school for many years and was a PTA mother and a Girl Scout Leader.

Over the course of her life Lola had two careers: she worked as a licensed daycare provider for fifteen years and after her daughters grew up she took classes to update her skills and became a family court clerk at the King County courthouse in downtown Seattle. After retiring at the age of sixty-five, she moved to Oregon to be closer to her two daughters. Sadly while in her 80’s Lola lost her ability to walk and was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, Meniere’s disease (hearing loss), and glaucoma (vision loss), but despite these challenges, she was always good natured and lived to be ninety-two.

Phyllis Van Driel-Clem is married and currently resides in Friday Harbor, WA; she retired from Compass Health (which is a community-based, non-profit organization in Washington that provides a wide range of behavioral health related services) in 2017. Vonnie’s sister Shirley Byrd relocated to Oregon and earned her RN from Linn-Benton Community College in June 2002; she is a passionate advocate for those struggling with substance abuse. Vonnie’s youngest sister Alicia lives in Federal Way, WA with her husband, who she has been married to since 1986. Todd Stuth remarried and lives in Kent, WA; he is currently employed as a flight instructor at Crest Airpark.

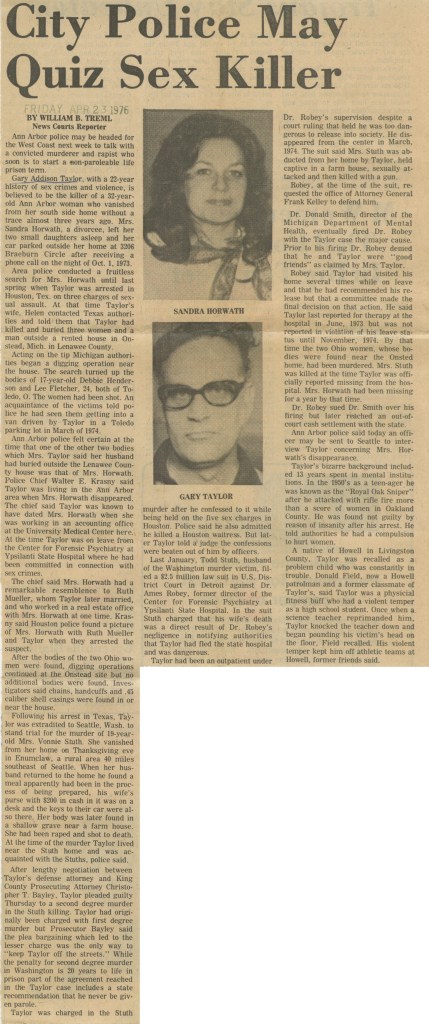

Gary Taylor is currently 89 years old and is still incarcerated in the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. Michigan investigators strongly suspect that he is also responsible for the disappearance of thirty-three year old Ann Arbor mother of three Sandra Horwath, who vanished without a trace on October 1, 1973. In 2002 detectives went to the prison Taylor was housed at and tried to speak to him about Horwath, but he refused to answer any questions.

Works Cited:

Barber, Mike, ‘Serial killers prey on ‘the less dead.’ (February 19, 2003). The Seattle Post-Intelligencer Reporter.

Gore, Donna. (March 14, 2014). ‘Two Desperate Housewives, First Support Group.’ Taken August 27, 2025 from ‘herewomentalk.com’

Hefley, Diana. (April 18, 2015). ‘For 40 years, group has been there in darkest times for crime victims.’ Taken August 9, 2025 from heraldnet.com

Forrest was active in Washington/Oregon roughly the same time as Bundy.

This is a rare occasion I was unable to find out any background information about the woman I was writing about: typically, I can come up with some helpful tidbit that helps me dig up more information about them, however I was unable to do that with Ms. Griswold. If anyone knows anything more than what I have here and would like to reach out to me about it, I will give you credit for your help.

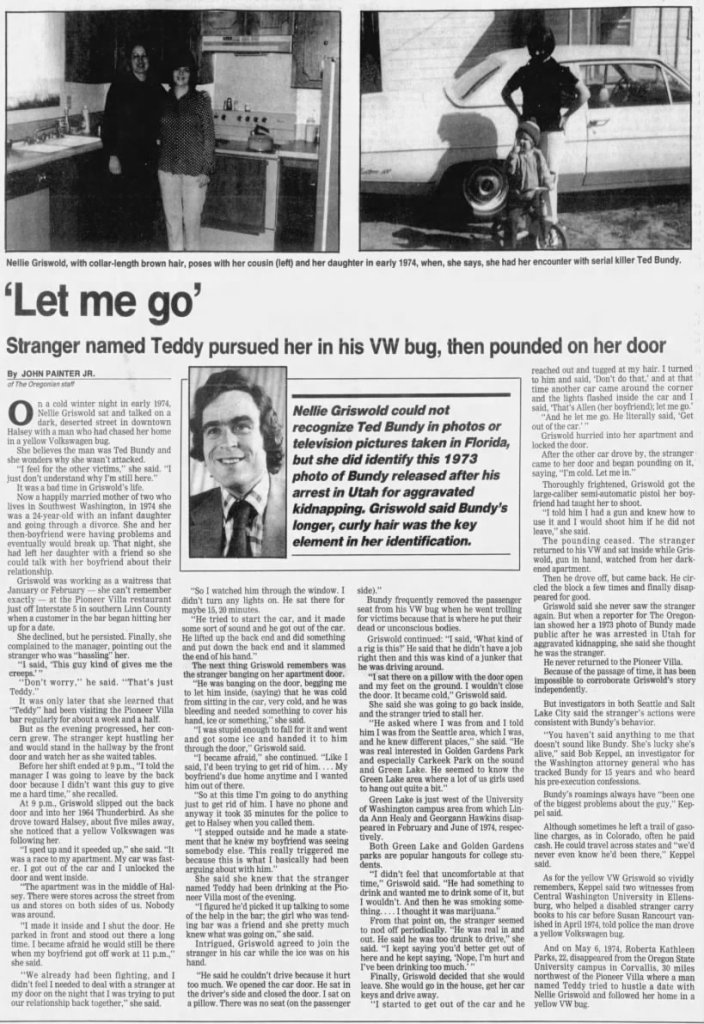

While I was driving to Michigan with my husband last week I stumbled across an article posted by another true crime Facebook Group called, ‘TB: I was Trying to Think Like an Elk’ that included an article published in February 1989 from The Oregonian discussing an encounter that Nellie Griswold may have had with Ted Bundy: Griswold, who lived in Halsey, Oregon in the early part of 1974, worked as a waitress in the restaurant part of The Pioneer Villa truck stop, located right off the I-5 in the southern part of Linn County.

In early 1974 (she wasn’t sure if it was January or February) Griswold was twenty-four years old, and one evening as she was working she noticed a man that matched Bundy’s description lingering around her POE: she told her boss ‘this guy kind of gives me the creeps,’ to which he replied, ‘don’t worry, that’s just Teddy’ and went on to tell her that he had been hanging around The Pioneer Villa’s bar semi-regularly for about a week and a half. Nellie said that she was going through a bad time in her life and at the time was newly divorced with an infant and was having relationship issues with her current-boyfriend (they eventually broke up); that night, she left her daughter with a friend so she could talk with her significant other about their relationship problems after she got out of work.

But as Nellie’s shift went on her worry only grew: the stranger kept trying to hustle her and repeatedly asked her out on a date (an offer that she politely declined) and stood in the hallway near the front door, just watching her. Before her workday ended at 9 PM she ‘told the manager I was going to leave by the back door because I didn’t want this guy to give me a hard time.’ A little after nine she left out the restaurants back door and got her 1964 Thunderbird and began the five mile drive to her apartment…. but as she made her way to Halsey she noticed a yellow VW Beetle trailing behind her: ‘I sped up and it speeded up. It was a race to my apartment. My car was faster. I got out of the car and unlocked the door and went inside. There were stores across the street from us and stores on both sides of us. Nobody was around. I made it inside and I shut the door.’

During an interview with reporter ‘John Painter Jr.’ with the newspaper ‘The Sunday Oregonian,’ Griswold said the strange man parked his car in front of her apartment building and stood out there a long time, just staring towards her residence: ‘I became afraid he would still be there when my boyfriend got off work at 11 PM. We already had been fighting, and I didn’t feel I needed to deal with a stranger at my door on the night that I was trying to put our relationship back together.’

According to Nellie, when she arrived home: ‘I watched him through the window. I didn’t turn any lights on. He sat there for maybe fifteen, twenty minutes. He tried to start the car, and it made some sort of sound and he got out of the car. He lifted up the back end and did something and put down the back end and it slammed the end of his hand.’

She went on to say that the next thing she remembered was the stranger frantically knocking on her apartment door: ‘he was banging the door, begging me to let him inside, (saying) that he was cold from sitting in the car, very cold, and he was bleeding and needed something to cover his hand, ice or something. I was stupid enough to fall for it and went and got some ice and handed it to him through the door. I became afraid. Like I said, I’d been trying to get rid of him… My boyfriend’s due home anytime and I wanted him out of there. So at this time I’m going to do anything just to get rid of him.’

Griswold went on: ‘I have no phone and anyway it took thirty-five minutes for the police to get to Halsey when you called them. I stepped outside and he made a statement that he knew my boyfriend was seeing somebody else. This really triggered me because this is what I basically had been arguing about with him.’

She also clarified that she was aware ‘Teddy’ had been drinking at bar most of the evening. “I figured he’d picked it up talking to some of the help in the bar; the girl who was tending bar was a friend and she pretty much knew what was going on.’ Intrigued, she agreed to go with him while the ice was on his hand: ‘he said he couldn’t drive because it hurt too much. We opened the car door. He sat in the driver’s side and closed the door. I sat on a pillow. There was no seat on the passenger’s side.’

Griswold went on to say: “I said, ‘What kind of a rig is this?,’ to which he replied that he didn’t have a job at the moment and it was the only option he had to get around: ‘I sat there on a pillow with the door open and my feet on the ground. I wouldn’t close the door. It became cold.’ When she announced that she was going to go back inside the stranger tried to stall her: ‘he asked where I was from and I told him I was from the Seattle area, which I was, and he knew different places. He was real interested in Golden Gardens Park and especially Carkeek Park on the sound and Green Lake. He seemed to know the Green Lake area where a lot of us girls used to hang out quite a bit.’ At the time in the 1970’s both Green Lake Park and Golden Gardens Park were popular hangouts for college kids.

Nellie continued: ‘I didn’t feel that uncomfortable at that time. He had something to drink and wanted me to drink some of it but wouldn’t. And then he was smoking something… I thought it was marijuana.’ After that, the man immediately appeared to become inebriated, and even nodded off periodically: ‘he was real in and out. He said he was too drunk to drive. I kept saying you’d better get out of here and he saying, ‘nope, I’m hurt and I’ve been drinking much.’’

Finally, the attractive young mother made the choice to finally leave, and ‘started to get out of the car and he reached out and tugged at my hair. I turned to him and said, ‘don’t do that,’ and at that time another car came around the corner and the lights flashed inside the car and I said, ‘that’s Alan (her boyfriend), let me go. And he let me go. He literally said, ‘get out of the car.’’

Griswold quickly ran to into her apartment and locked the door behind her, and after the other vehicle drove by, the man returned to her apartment and began pounding on the door, saying loudly, ‘I’m cold. Let me in.’ Thoroughly spooked, she went back to her bedroom and got her boyfriend’s large semi-automatic pistol that he had also taught her to shoot: ‘I told him I had a gun and knew how to use it and would shoot him if he did not leave.’ The pounding immediately stopped.

Looking out the window, Nellie said that the man went back to his Bug and just sat there for a while then circled the block a few times before he eventually disappeared for good; she never saw him again, and he never returned to The Pioneer Villa. Because of how much time had passed her story was impossible to corroborate, however investigators in SLC and Seattle said the man’s actions were consistent with Ted’s behavior. According to Dr. Robert Keppel, ‘you haven’t said anything to me that doesn’t sound like Bundy. She’s lucky she’s alive.’

It would be fair to say that at the time of Nellie’s attack Bundy had a lot of spare time on his hands: he was taking a break from school (he didn’t begin law school for the second time until later that September) and happened to be in between jobs at the time (in September 1973 he was the Assistant to the Washington state Republican chairman, and remained unemployed until May 3, 1974 when he started at the Department of Emergency Services in Olympia). He was still in a (fairly) committed relationship with Elizabeth Kloepfer at the time and was residing in the Roger’s Rooming House on 12th Avenue NE in Seattle.

As we know, Ted’s first confirmed attack took place on January 4, 1974 when he brutally assaulted Karen Sparks in her basement apartment near the University of Washington in Seattle. Additionally, he abducted and killed Lynda Ann Healy not far away on January 31, 1974… so its safe to say Bundy was definitely active at the time Griswold claims she was hassled by him.

According to Dr. Keppel, Bundy’s habit of roaming across the Pacific Northwest had always been ‘one of the biggest problems about the guy,’ and despite there being a trail of credit card receipts for gas there were many times that he paid for fuel in cash: meaning, he could travel across multiple state lines and investigators ‘never even know he’d been there.’ As for the yellow VW that Griswold so vividly remembers, Keppel said two witnesses from Central Washington University in Ellensburg told police about a man that drove a similar vehicle that tried to pick them up; also, on May 6, 1974 Roberta Parks vanished without a trace from the Oregon State University campus in Corvallis, which is only thirty miles northwest of the Pioneer Villa. I know there’s a lot of back and forth as to EXACTLY what color Ted’s car is… but I don’t think it’s a coincident that Death from Family Guy drove a bright yellow Beetle.

When showed a picture of the serial killer, Nellie was unable to ID Bundy, but she was able to identify a photo of him taken in 1973 that was released after his arrest two years later in Granger, Utah for the aggravated kidnapping of Carol DaRonch. She said that Ted’s ‘longer, curly hair’ was the most important part of her identification. Griswold told Painter that she felt ‘for the other victims. I just don’t understand why I’m still here.’ At the time of the interview in February 1989 Griswold said that she was a happily married mother of two and was living with her husband and kids in Southwest Washington.