University of Washington.

Martha Feldman, Rape Report.

I’ve had Martha Feldman’s rape report in my drafts folder for over a year now, and I’m not sure why I didn’t post it yet. I started doing some digging into her background and as I was really getting into it, I realized that she didn’t ask for this to happen and this file was most likely only released due to a TB related FOIA request: she doesn’t want her personal life to be dissected fifty years after what was most likely one of the worst events of her life, so I am not going to go into her background and will strictly stick to the facts on the police report (especially since she specifies in it that she wishes to remain anonymous). I will say that she went on to lead an incredibly successful life, but I’m not going to elaborate any further. Feldman isn’t a Rhonda Stapley or Sotria Kritsonis, who ‘came forward’ years after their alleged run-in’s with Bundy looking for attention and notoriety (and in Stapley’s case, money). I mean, there’s a fair chance that Ted wasn’t Martha’s rapist.

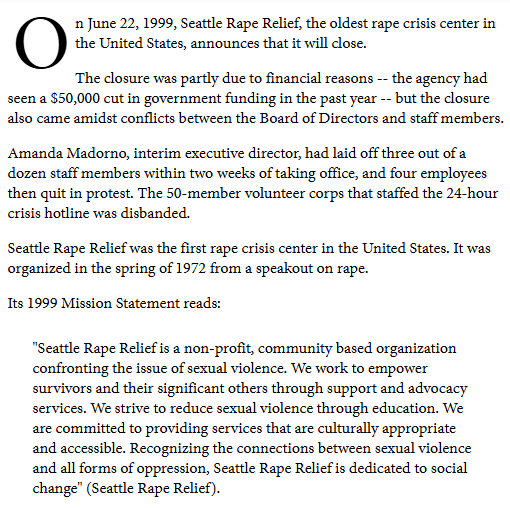

According to the police report that Feldman filed on March 7, 1974 with the Seattle Police Department at the YWCA (located at 4224 University Way NW), she was raped by an unnamed assailant five days prior on Saturday, March 2 around 4:15 AM; she first disclosed her attack to a woman named Maria at the Seattle based organization ‘Rape Relief’ later that morning at around 7:30; from there, she sent two young women over, and they brought her into Harborview Hospital for a medical exam, which was given by a Dr. Shy at around 8:30 AM (where we know Bundy interned as a counselor from June 1972 to September 1972); the Seattle PD were notified later that evening.

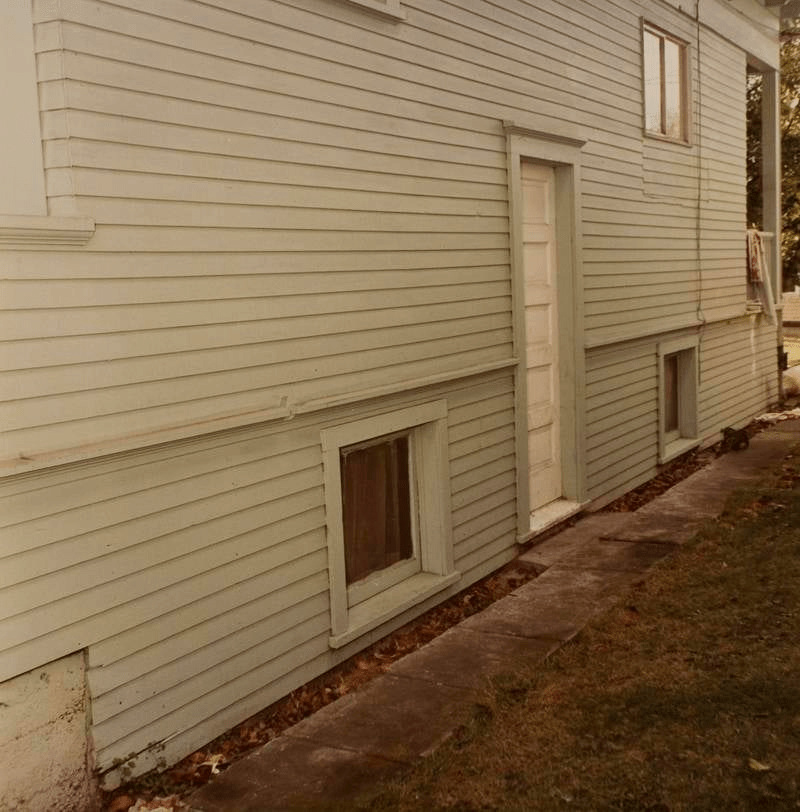

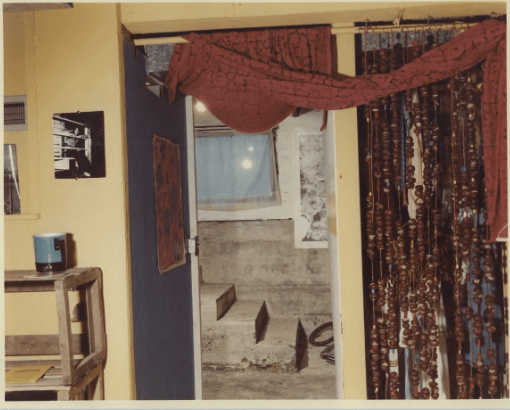

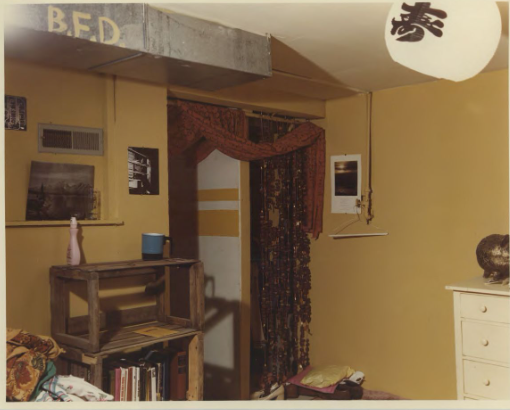

Feldman told investigators that at around 1:30 AM on February 28, 1974 she heard something unusual but when she got up to investigate nothing was amiss; later in the same afternoon a friend of hers noticed that the screen had been removed from one of her windows (this reminds me of when Ted removed Cheryl Thomas’s screen from her window four years later in Florida). Martha’s assailant broke into her apartment around 4 AM and said that he didn’t ask her for money or valuables, and she even had some of her good jewelry sitting out and it remained untouched (in fact, the man didn’t appear to touch anything in the apartment). Personally, I think it makes sense that Bundy wouldn’t have stolen anything expensive, because by that point Liz already knew he was stealing and he was making a half-hearted attempt of not doing it.

Also, according to the report Feldman was moving out of her apartment and would be in touch with her new address; it does not clarify if she left because of her rape. She did not want her parents notified of her assault and said that she was ‘careless in not drawing her drapes or locking the window.’ After a few unsuccessful attempts to reach her by phone, detectives finally connected with her and on March 6th stopped by her apartment so she could sign a medical release form and speak to her more about what happened. Feldman told them that her assailant had been between twenty to twenty-four years old based off his ‘build and voice,’ and said that she never saw his face because he had a dark navy watch cap pulled over his head and down below his chin (it only had slits for the eyes that she suspected were made by him and specified that it had ‘not been a ski mask’); she said that she didn’t know his hair color but was certain he was white because she ‘saw his arms’ (she also said they had no hair on them).

Feldman said that early on the Saturday morning of her assault she went to bed around 1 AM (one other place in the police report said it was at 2 PM), and even though her shades were drawn one of the curtains were slightly agape, and she said it was easy to look in her one window and see that her extra bed was empty and that she was alone (she said that roughly ¾ of the time a friend stayed with her). It was probably 4 AM when she was suddenly awakened by something (she believes by him opening then shutting the window). Martha said that she’ had forgot to put the wooden slot in the window to lock it and although it would be difficult to see it was not there in the dark, he must have seen it as be took off the outer screen to reach the window.’ When she opened her eyes, a man she didn’t immediately recognize was standing in her doorway, and she said at first she only saw his profile and noticed there was something bright illuminating her living room and realized he had left his flashlight on the table (and that he had left it on). After her assailant came in her room he sat on her bed and assured her that he wasn’t going to hurt her and that he wouldn’t use his weapon on her as long as she didn’t scream, then proceeded to pull a hunting knife out from his back pocket, one that was dark and had a ‘carved bone handle’ with streaks on it. When she asked him how he got into her apartment he told her that it was ‘none of her business.’

Martha told the detectives that the man had been wearing a white, short-sleeved t-shirt and Levi’s, but was wearing not wearing a coat or sweater (even though it had been cold outside). She also said that his voice sounded like a Northwesterner and he seemed ‘well-educated,’ and possibly could have been a student at the nearby University of Washington. Feldman said that she didn’t recall that her assailant was wearing any jewelry or a watch and he had been drinking but was ‘not drunk’ and after about eight to ten minutes of talking he pulled out some tape out of his pocket and used it to cover her eyes.

He then turned on her bedroom light and left it on as he undressed her, unzipped his pants, then had sexual intercourse with her. When finished, he taped her hands and feet up ‘just to slow you down,’ turned off the light, covered her up with some blankets, said ‘go back to sleep,’ then left; the tape was later put into evidence. She heard him go out to the living room, open the window then run down the back alley; she listened but heard no car start up. Martha said he was very calm and sure of himself and felt that ‘he has done this before,’ although he didn’t say anything that made her think it was anything other than his first time. Feldman told detectives that she believed she could identify her assailant (even though her eyes were taped shut), and was usually home days as she had classes in the evening.

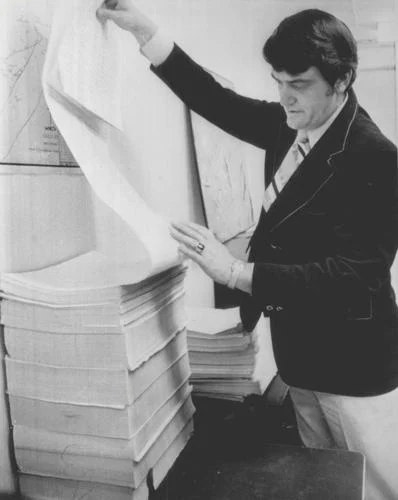

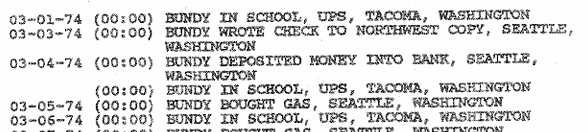

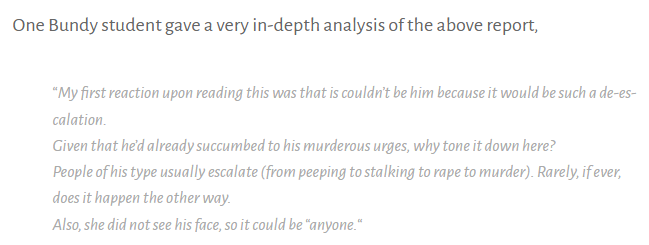

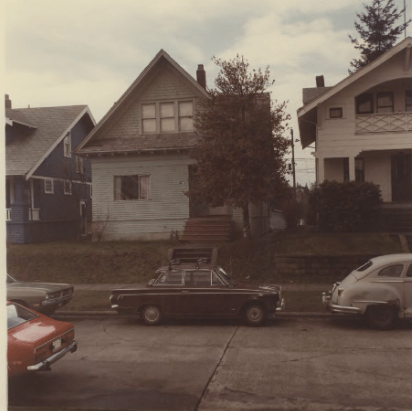

At the time of her assault Feldman lived at 4220 12th Avenue NE Unit 14, which was four houses and just a minute’s walk away for Bundy, who was living at the Rogers Rooming House just down the street at 4214 12th Ave NE (the building she lived in has since been torn down and in 2023 a new complex was built in its place). Ted’s whereabouts aren’t accounted for specifically on March 2, 1974, however he was placed in Seattle/Tacoma both the day before and after. He was in between employment at the time and had been without a job since September of 1973 (when he was the Assistant to the Washington State Republican chairman) and remained unemployed until May 3, 1974 when he got a position with the Department of Emergency Services in Olympia (he was there until August 28, 1974, which is right before he left for law school). On the last page of the eight-page document is a blank page with a scribbled note: ‘this is the case, I thought of for Bundy. Think there would be a print on the tape?’

Bundy went on to abduct then murder Donna Gail Manson from Evergreen State College in Olympia on March 12, 1974. On her website ‘CrimePiper, Erin Banks points out that on a social media post about Feldman one commenter remarked on the face that the assailant pulled out a ‘carved knife handle,’ and it just so happened to match the description of a rare knife that had been ‘stolen’ out of Bundy’s girlfriend Elizabeth Kloepfer’s VW Bug a short period later. That same person went on to say that ‘the fact that he wasn’t wearing a jacket, just a T-shirt, even though it was cold outside, seems to indicate he lived nearby too.’

Some Miscellaneous Original Bundy-Related Notes, Courtesy of King County.

Karen Sparks, Case Files: Part One.

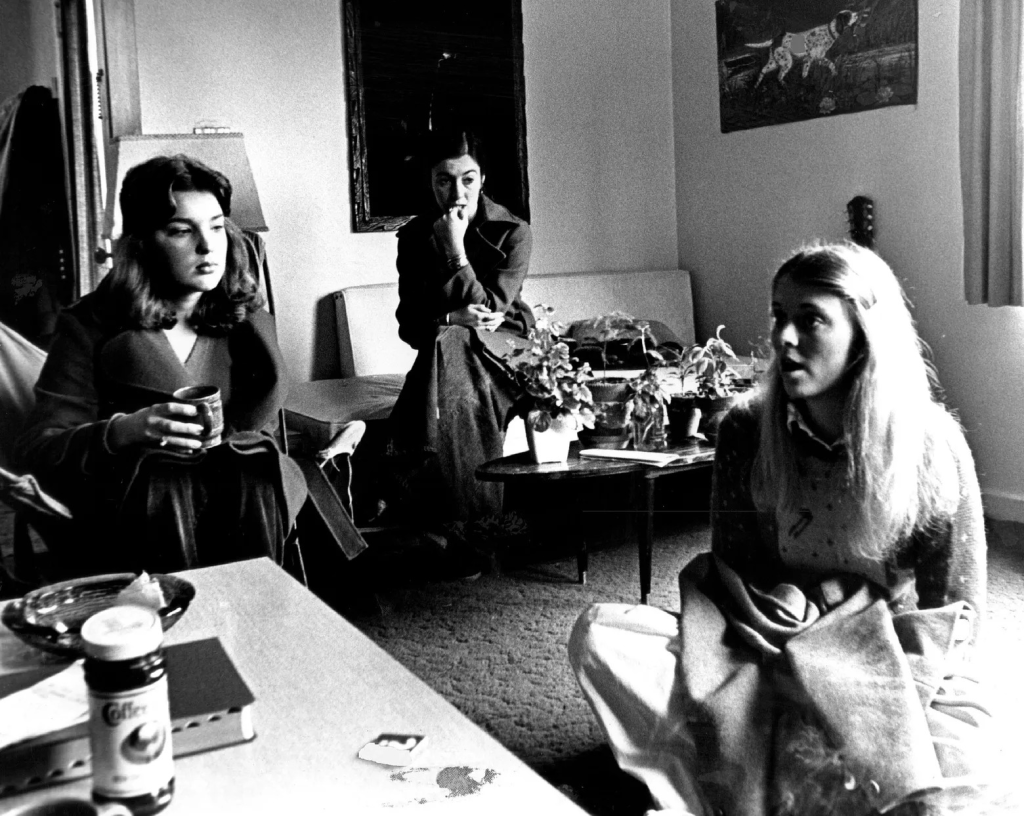

Document courtesy of the King County Sheriff’s Department. Over the years Karen has been given various pseudonyms, including ‘Joni Lenz,’ ‘Mary Adams,’ and ‘Terri Caldwell’ (in an attempt to protect her identity) and told her story for the first time in the 2020 Amazon docuseries, ‘Ted Bundy: Falling for a Killer.’

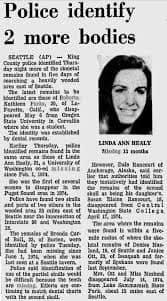

Lynda Ann Healy: Information & Pictures from the King County Archives.

In May 2025 I reached out to King County to see if there was a chance I could visit their archives to look at their information related to the Ted Bundy investigation. Where visiting didn’t work out they were kind enough to send me a link via Dropbox that contained tens of thousands of pages of information related to the investigation. Here is everything I could find related to Lynda Healy.

Karen Sparks-Epley.

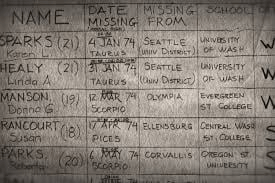

In the early morning hours of January 4th, 1974, Ted Bundy brutally assaulted college student Karen Sparks at 4325 8th Avenue NE in the University District of Seattle; she was his first known victim. Miraculously, he didn’t kill her, but he did leave her with numerous long-term injuries that she still struggles with to this day. The house she used to reside in no longer exists as it was torn down sometime in 1985 to make way for a new four-story apartment block called ‘Westwood Apartments.’

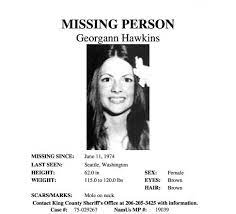

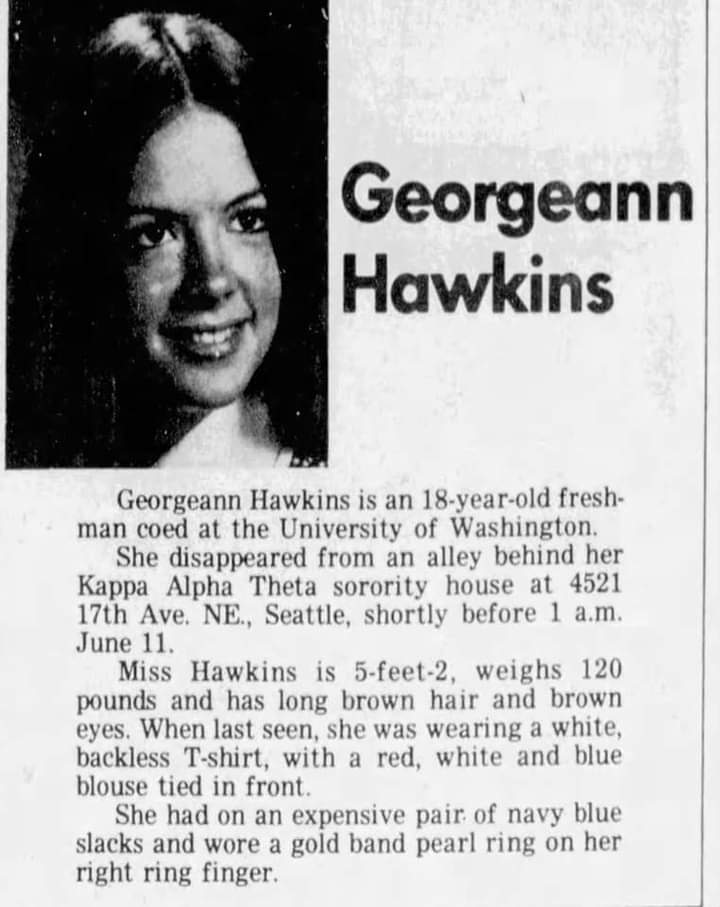

Georgann Hawkins.

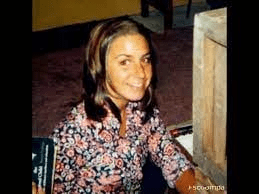

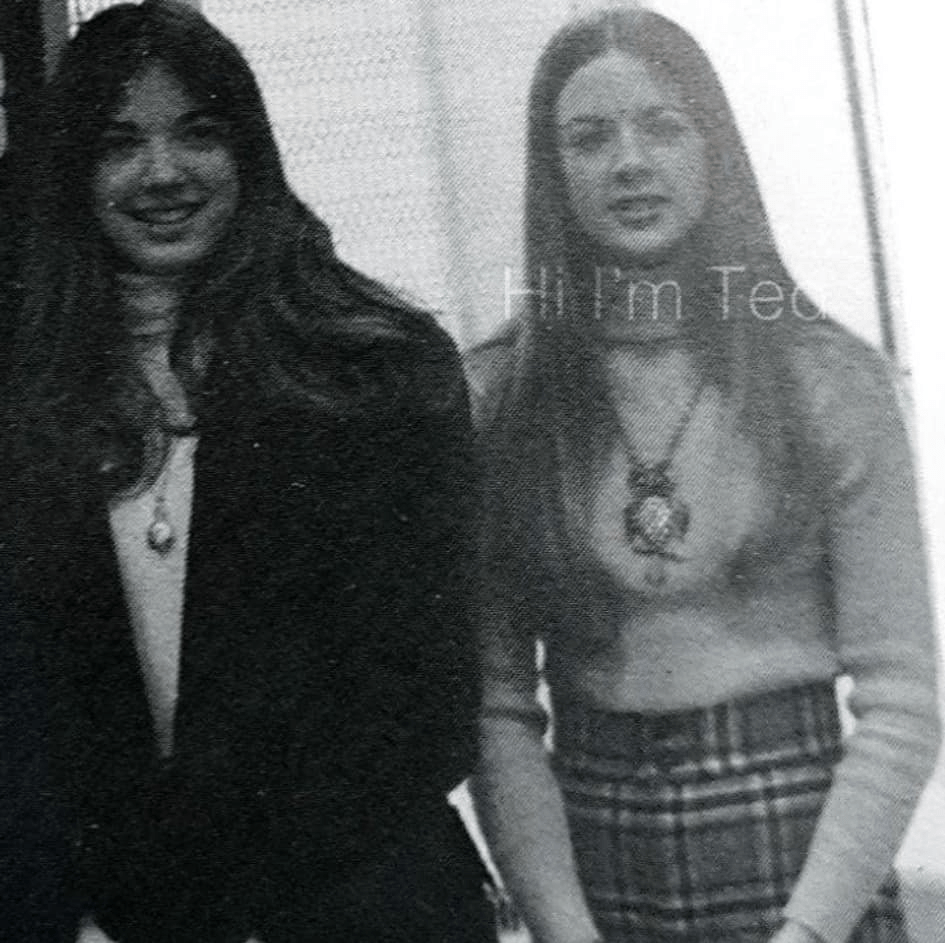

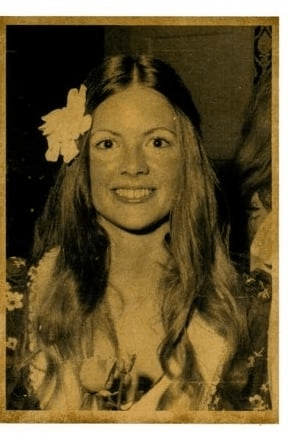

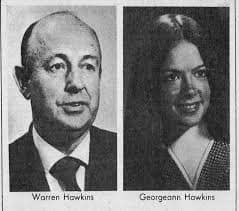

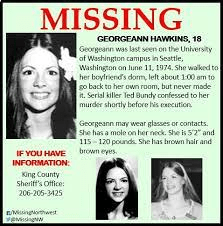

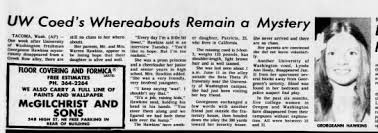

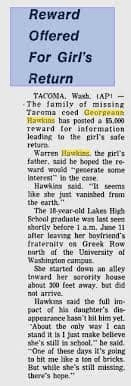

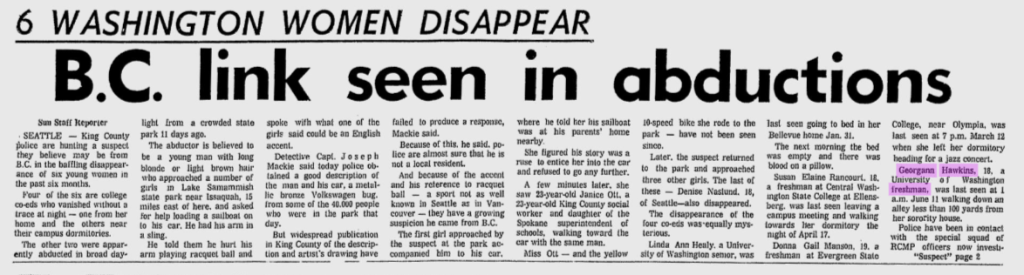

Georgann Hawkins was born on August 20, 1955 in Sumner, Washington to Warren and Edith Hawkins. She had an older sister named Patti and both girls were brought up in an upper middle class, Episcopalian household. Affectionately nicknamed ‘George’ by family and friends, Mrs. Hawkins described her daughter as a ‘wiggle worm’ because she was always full of energy and was unable to sit still. Georgann seemed to be universally adored by everyone around her, and she was always surrounded by a close-knit group of friends. At one point in her early childhood Hawkins went through a bout of Osgood-Schlatter Disease, which is described as painful inflammation found just below the knee that is made worse with physical activity and made better with lots of bed rest. One or both knees can be affected by this disease and flare-ups may occur after the initial episode has passed. Thankfully it never came back after George’s initial bout (although she was left with several small, barely noticeable bumps just below her patellae).

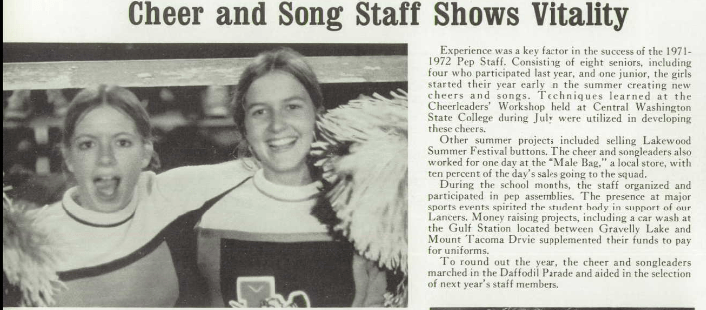

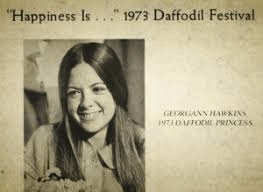

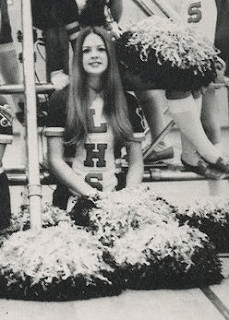

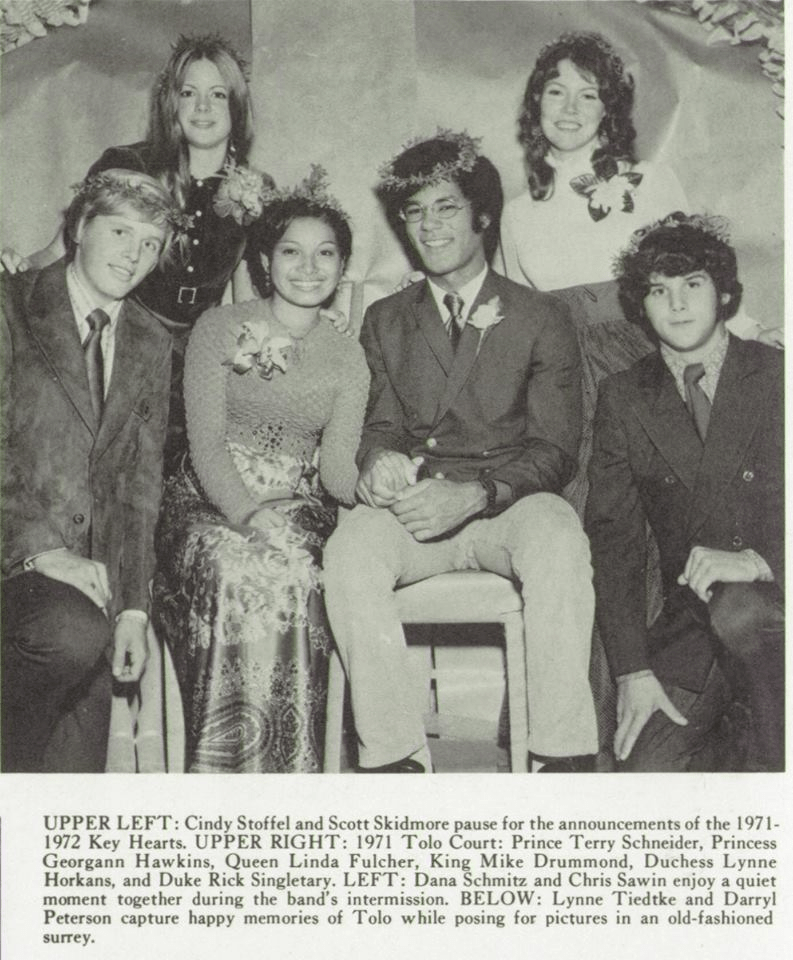

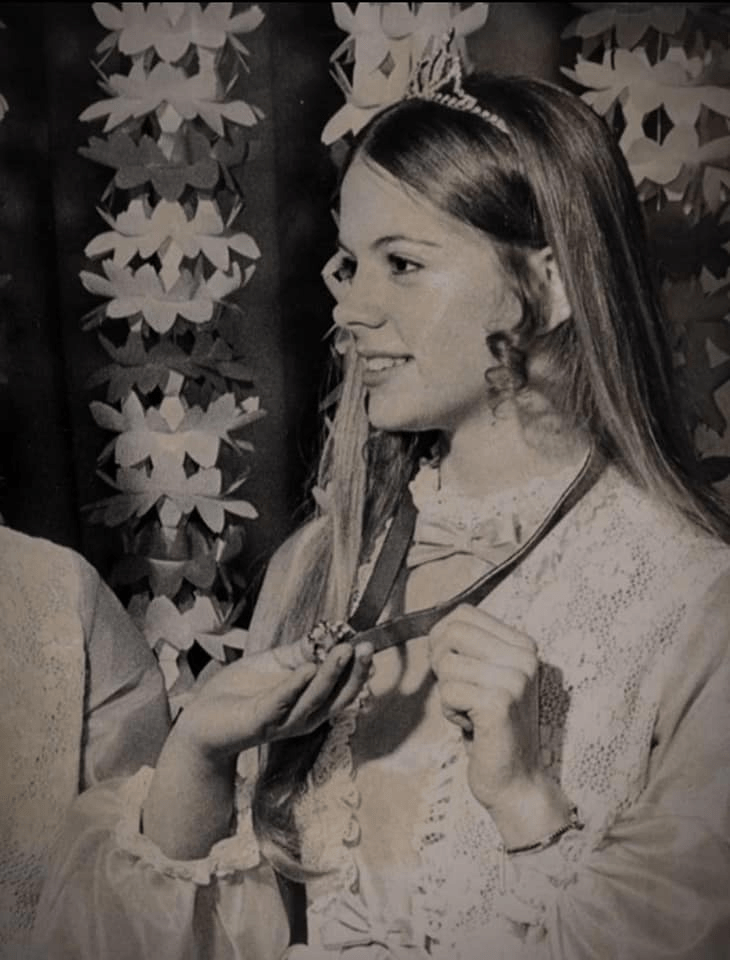

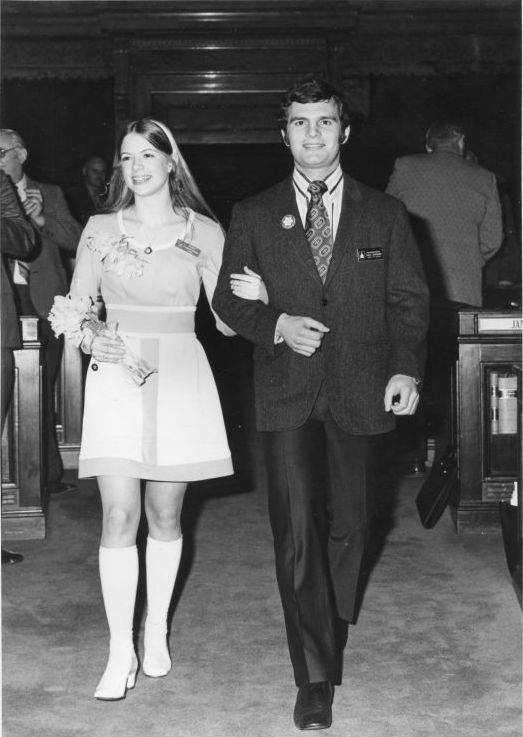

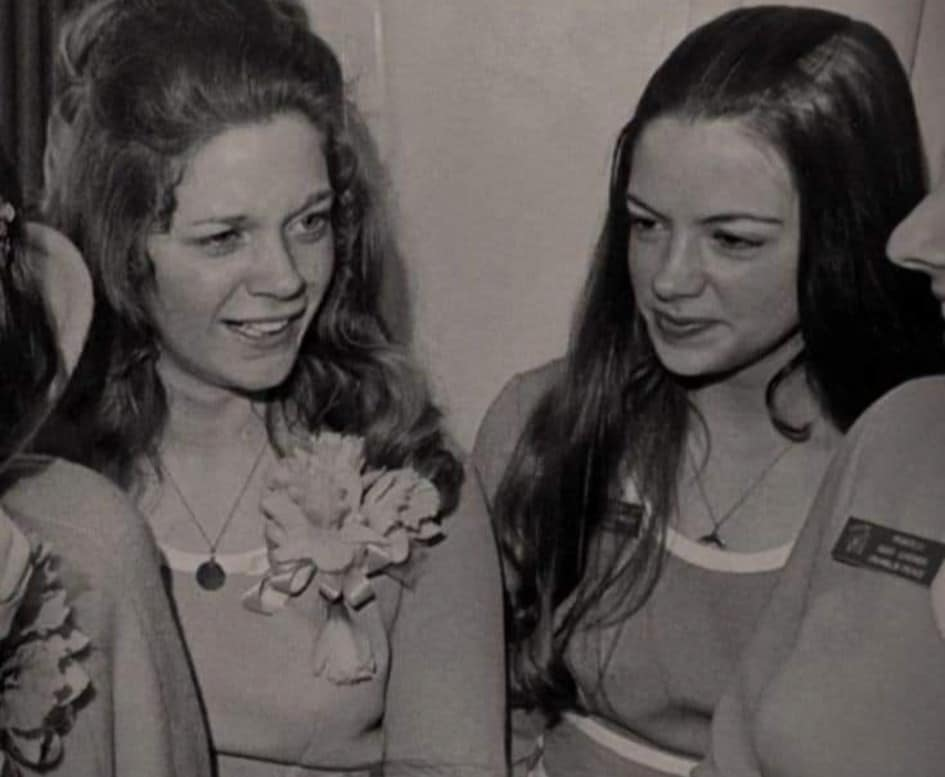

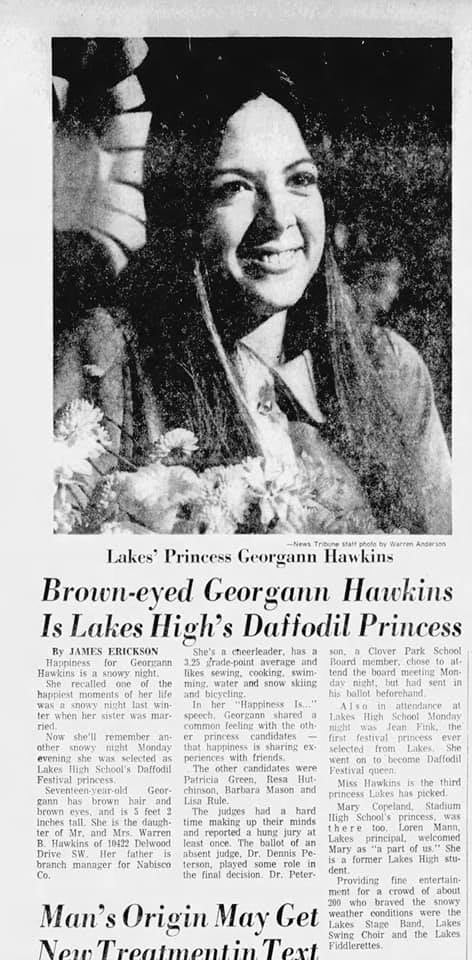

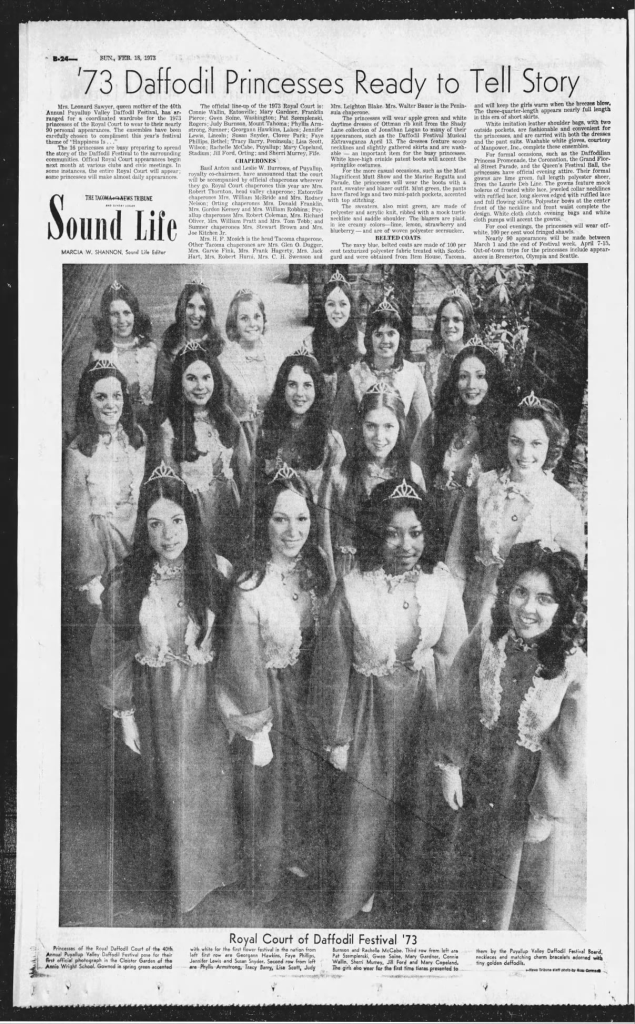

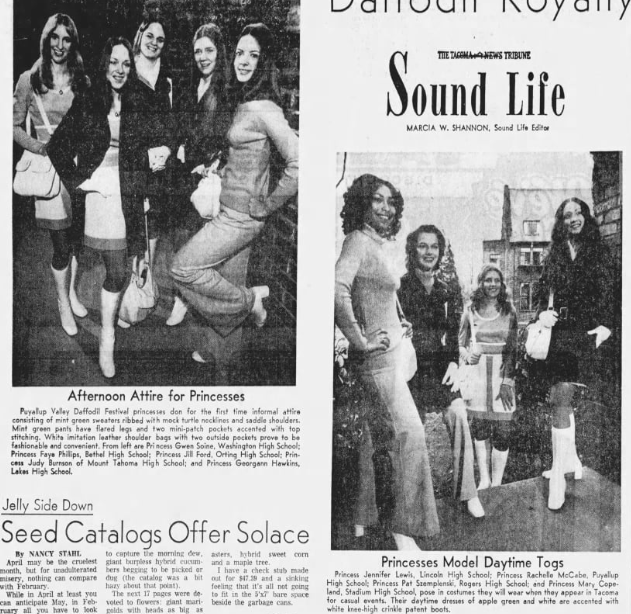

Despite her health challenges, Georgann went on to become a star athlete at Lakes High School in Lakewood, Washington: she was on the swim team in her early years but eventually gravitated towards cheerleading, winning numerous medals and competitions while on her high schools cheerleading squad (where she cheered all four years). In addition to her impressive athletic accomplishments, Hawkins was also a straight A student throughout the entirety of her academic career. During her senior year in 1973, Georgann was awarded with the title of princess to the royal court of the annual Washington Daffodil Festival. As Daffodil Princess, she traveled around Washington State with the other court members and their ‘duties’ involved being interviewed by newspapers, meeting children, riding in parades, attending concerts, and signing autographs at charity events. Georgann even gave a speech in the spring of 1973 addressing lawmakers at the Washington State Legislature.

Patti Hawkins went to Central Washington University in Ellensburg, which is the same school that Susan Rancourt attended before she was abducted by Bundy in April 1974. Georgann originally planned on following in her sisters footsteps and attending CWU as well, however her mother was strongly against it; she wanted her younger daughter to attend college at the University of Washington Seattle Campus, which was only about 30 minutes away from Sumner. Agreeing to this arrangement, Mr. and Mrs. Hawkins paid for Georgann’s tuition, books, room and board. To earn some extra spending money, she worked in Seattle throughout the summer, occasionally returning to her family home on weekends. The final time Georgann saw her parents was on Mother’s Day weekend of 1974.

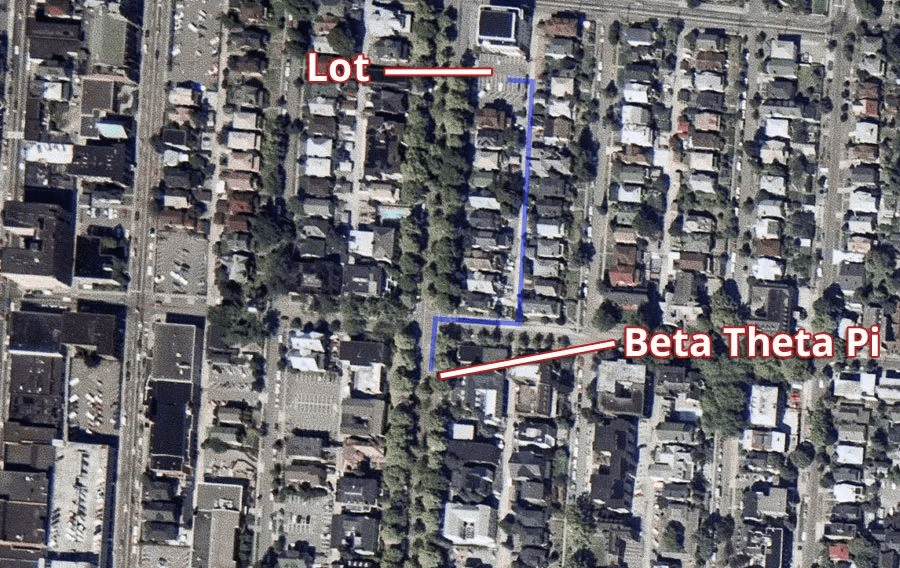

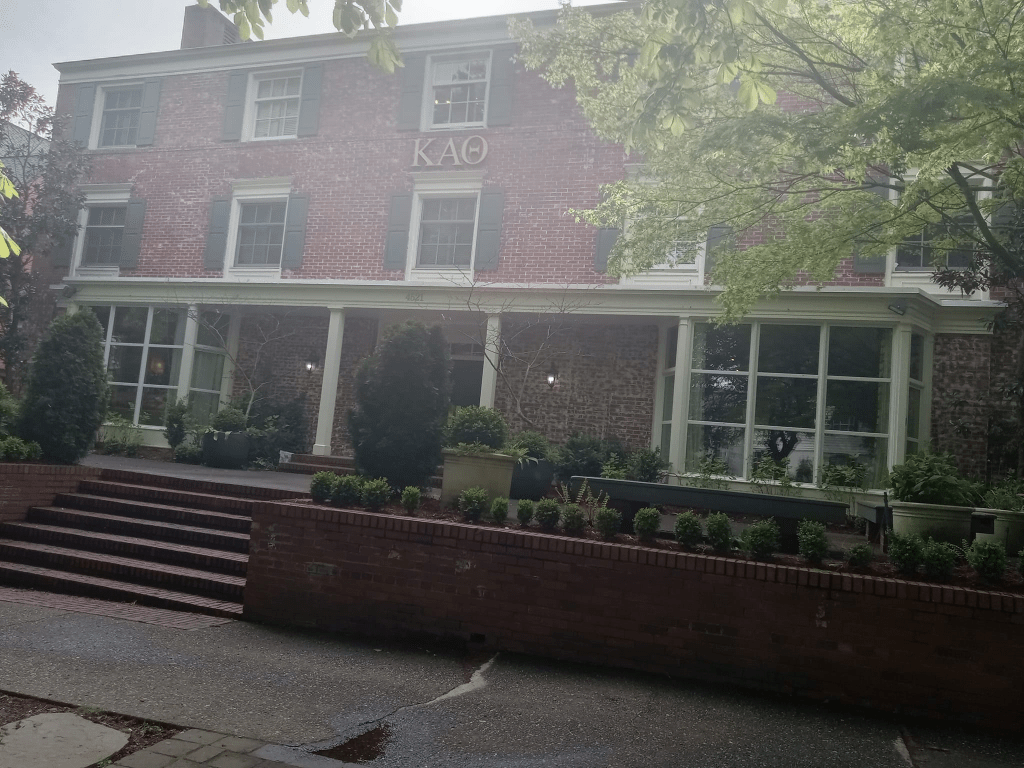

Georgann’s freshman year at the University of Washington was a busy one: she joined the Kappa Alpha Theta sorority and decided to major in either broadcast journalism or reporting. Despite having some troubles with a Spanish course she maintained a straight A GPA and found love with a Beta Theta Pi fraternity brother named Marvin Gellatly. Georgann planned to return to her parents house for the summer on June 13th and had plans to start a summer job on Monday, June 17th.

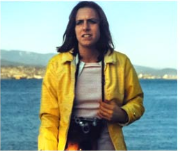

At the time of her disappearance in spring 1974, Georgann stood at a petite 5’2” and weighed a mere 115 pounds. She has long chestnut hair that went down her back and big, doe-like brown eyes. Earlier on the day on June 10th, Hawkins called her mother to tell her she was going to study as hard as she possibly could for her next days Spanish final so she wouldn’t have to retake it later. But before hitting the books she went to a party, even imbibing in a few mixed cocktails. But, because she needed to study didn’t stay long; Hawkins did mention to a sorority sister that she was planning on swinging by the Beta Theta Pi House to pick up some Spanish notes from her boyfriend. She arrived at the frat at 12:30 AM on June 11 and stayed for approximately thirty minutes. After getting the notes and saying goodnight to her beau, Georgann left the fraternity house for her sorority house, which was only about 350 feet away.

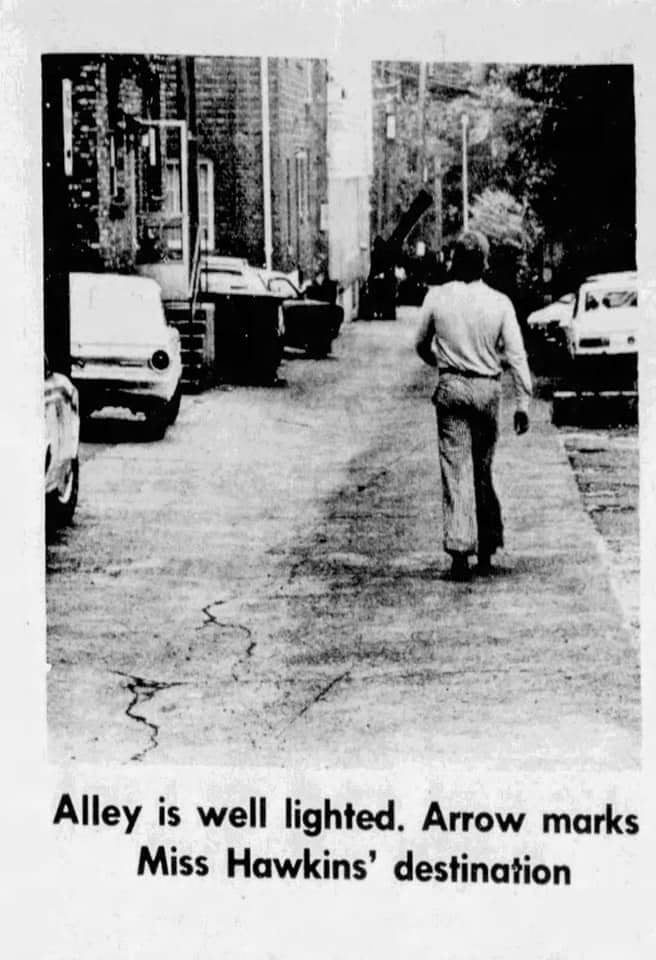

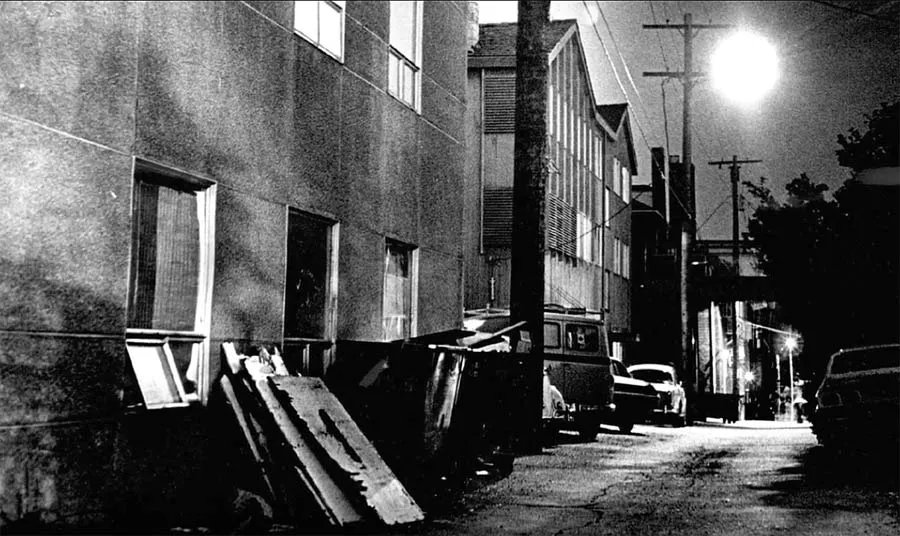

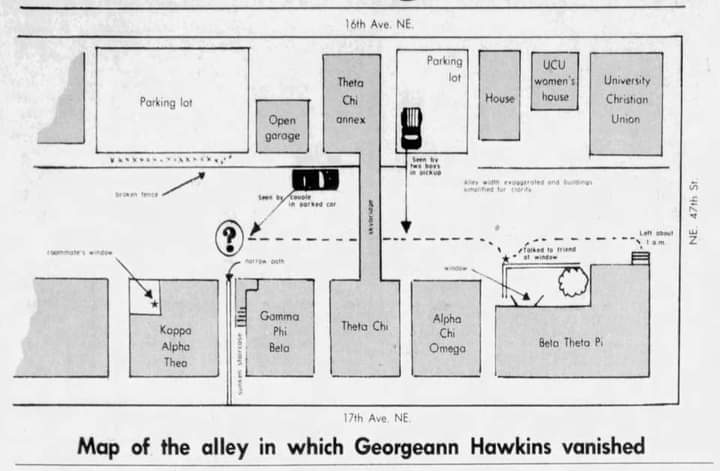

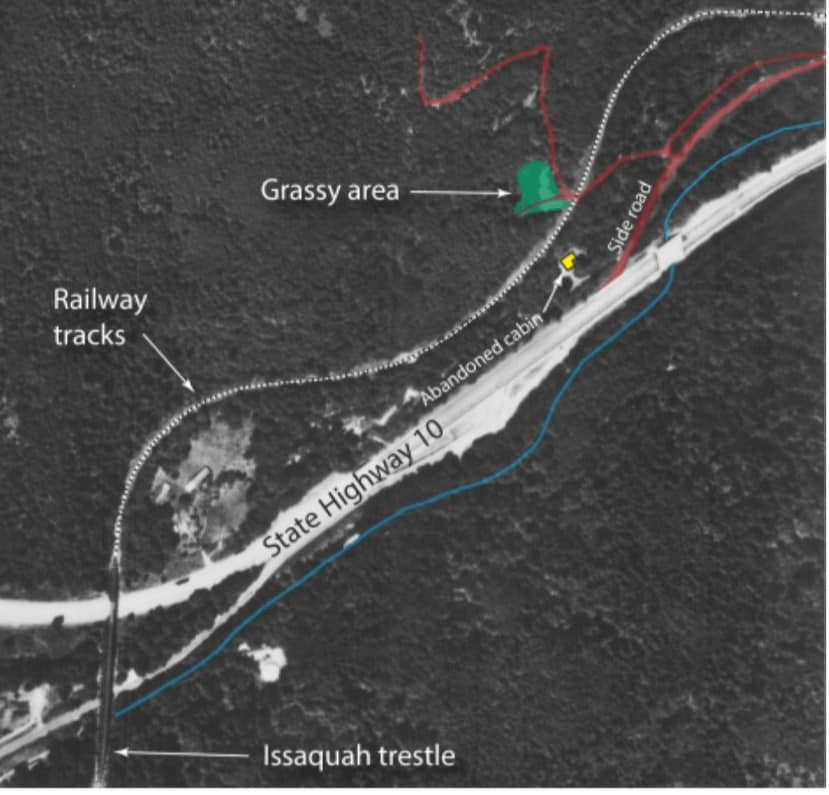

Although typically a very safe and cautious young woman, Georgann thought nothing of this short walk that she took hundreds of times before, as it was in a well lit and busy area. While on her way of what should have been just a quick jaunt home, a friend called out to her from his window and she stopped to chat for a few minutes. She said goodnight to him and continued her short walk back to her dorm. Hawkins sorority sisters knew something wasn’t right when the typically reliable George didn’t arrive home two hours later. One of them even called her boyfriend, who informed her that she left his place at around 1 AM. After hearing this, the sister woke the housemother, and together they waited up for Georgann until morning. When morning came and she still didn’t arrive home they called Seattle police, and because of the recent disappearance of fellow University of Washington student Lynda Ann Healy, they immediately sprung to action. They later were informed that one of the other housemothers had awoken that night to a high pitched scream: she thought it was some people joking around and went back to sleep. Bundy confessed to Georganns murder moments before his execution, and though he was foggy on some of the more specific details he distinctly remembered how kind and trusting she was. He went on to say that he asked her for assistance carrying his briefcase to his car (because of his prop cast), and she happily obliged. As Bundy was approaching the young coed he pretended to fumble with the briefcase he was carrying. This was a common practice Bundy used in order to gain his victims trust and get them to lower their defenses; he later switched things up a bit and used an arm sling during his Lake Sammamish abductions (most likely because he couldn’t drive with a ‘broken leg’). As she bent over to put the briefcase in his vehicle, Ted grabbed a conveniently placed crowbar and knocked her out with a single blow to the head. He then put George’s tiny body in the passengers seat of his car and drove off into the night, never to be seen again. Haewkins briefly regained consciousness and in her confused state asked Bundy if he was there to help study for her Spanish exam. He then knocked her unconscious again, pulled his VW Bug over to the side of the road near to Lake Sammamish State Park and strangled her using a piece of rope. Before his execution he claimed that part of her remains were included in those found at his Issaquah dump site.

The day after her brutal murder, Bundy returned to check on Georgann’s body and discovered that one of her shoes was missing. He immediately began to worry that it had fallen off in the parking lot during the abduction and that someone might remember seeing his car parked in the area. Ted was also worried people were going to piece things together because just two weeks prior he had attempted the exact same abduction technique on a different young woman but something spooked him and he decided against it. He was terrified that this unknown woman might come forward and mention the strange encounter if Hawkins belongings were discovered in the same parking lot. The morning after Hawkins abduction, law enforcement taped off the alley and searched it thoroughly for any evidence… but they left the parking lot where Bundy first approached her untouched. Because of this oversight, he was able to return at roughly 5 PM the next evening and retrieve the missing shoe as well as both of Georgann’s earrings that were misplaced as well.

Bundy also claimed he returned to Hawkins body again on June 14th, and at that point made the decision to cut off her head. His third (and final) post-mortem visit to her remains occurred about a week or two later, when he came back to ‘see what was going on.’ During his death row confession, Ted also hinted at acts such as necrophilia so who knows what he meant when he said he went back to ‘see what was going on’ with poor Georgann’s corpse. While going through the bones recovered from the Issaquah dump site, forensic experts found a femur they strongly thought to be Hawkins but is considered ‘impossible to identify.’ It’s also been said that Bundy himself admitted that one of her femur bones discovered at the Issaquah dump site was Georgann’s, but this statement has never been confirmed.

I’ve always wondered about Georgann Hawkins’ family and how they coped with the loss of their daughter. Many family members of other Bundy victims have been vocal with their opinions regarding Bundy’s fate and what happened to their loved ones (specifically Lynda Healy’s sister (Laura) was active in the Amazon mini-series “Falling for a Killer” as well as Susan Rancourts Mom and Sister) but it was tough for me to find anything about Mr. and Mrs. Hawkins. I did stumble across an article Georgann’s mother did with “Green Valley News” titled “Georgann Hawkins died at the hands of Ted Bundy, but that’s not how her mom wants her remembered” that was published on June 11, 2014. In it, Mrs. Hawkins fondly remembers her daughter, saying that “she was a very self-confident little girl … she wasn’t vain, she wasn’t arrogant and she wasn’t snooty. That’s why kids liked her.” She went on to say that her daughter was an avid swimmer who was active in the Brownies (however swimming eventually fell to the wayside once she discovered boys). Years after Theodore Robert Bundy was executed for his crimes against humanity by the State of Florida Georgann’s friends held a memorial for her at their alma matter: Lakes High School. Warren and Edie Hawkins did not attend. She explained, ‘my feeling at the time was, ‘What was it for,’ you know? It wasn’t going to help me any.’ She went on to elaborate that she didn’t keep in touch with anyone in her daughters life nor did she want to. Over the years many newspapers and magazines reached out to the Hawkins family for interviews about their beloved daughter but they turned them all down (aside from a single sentence Edie gave to the associated press after Bundy was executed, saying ‘I’ve never, ever, ever dwelt on how she died. I didn’t want to know how she died’). She didn’t like the idea of anyone making money off the death of her daughter.

THIS was an incredibly eerie experience for me. I felt a lot of sadness and fear at this particular site. When my Google Maps alerted me when I came to the supposed exact location (figured right down to latitude and longitude) I didn’t linger long, plus there was a cop just sitting there, watching the area.

2. As Hawkins is walking back to her sorority house, Bundy approaches her on crutches and asks for help carrying his briefcase to his car.

3. Once they are in the parking lot, he hits her over the head with a crowbar and kidnaps her.

Photo courtesy of OddStops.

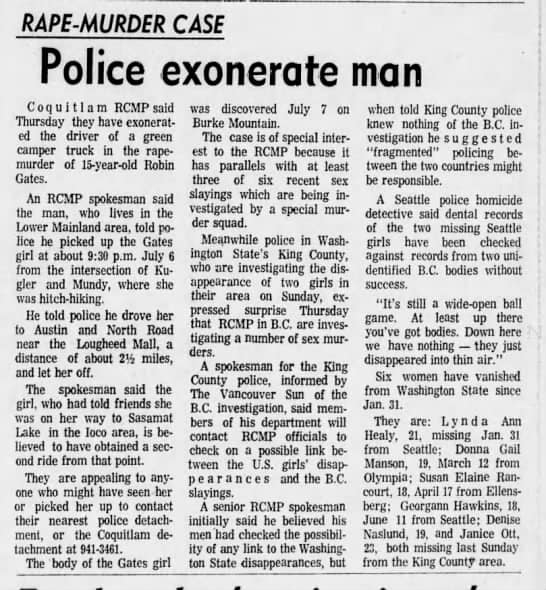

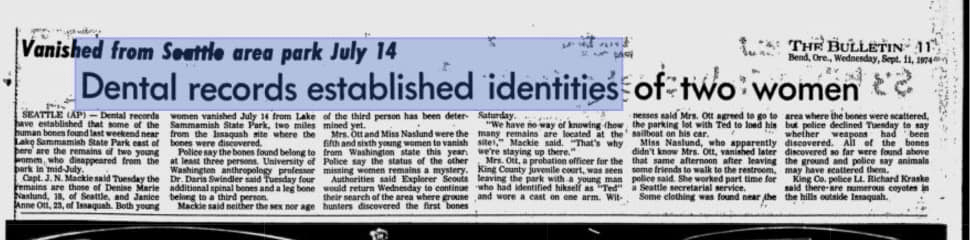

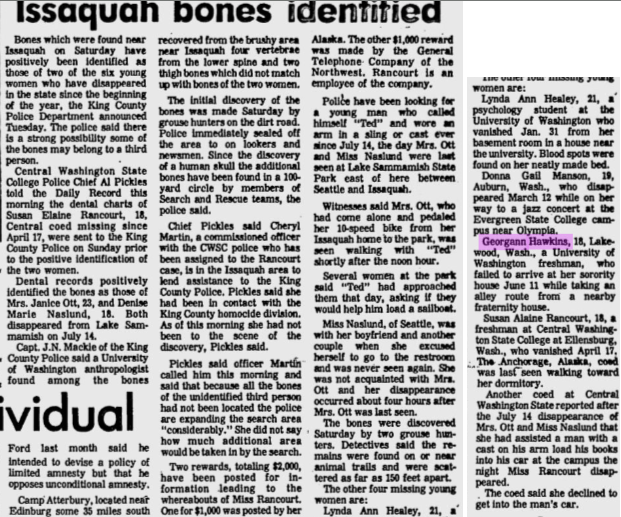

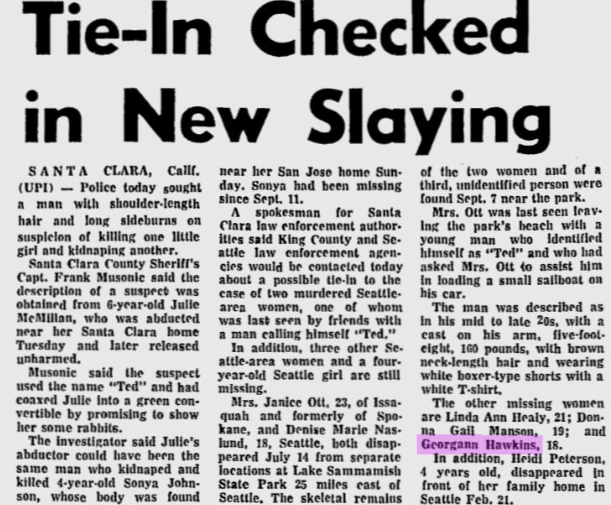

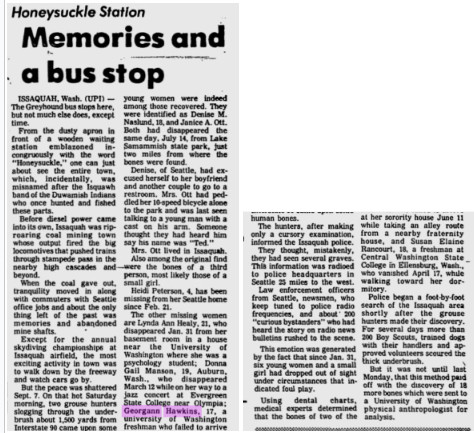

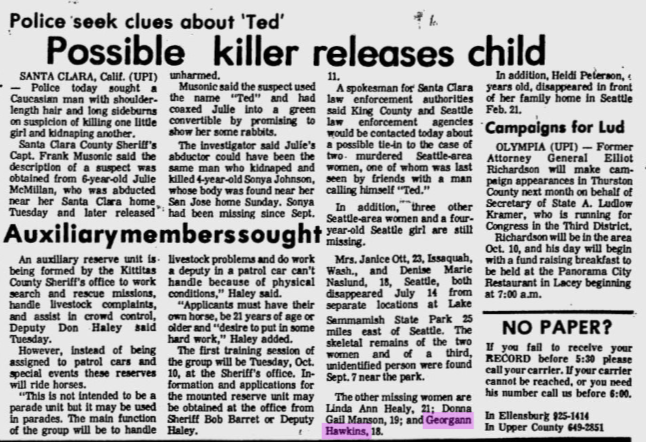

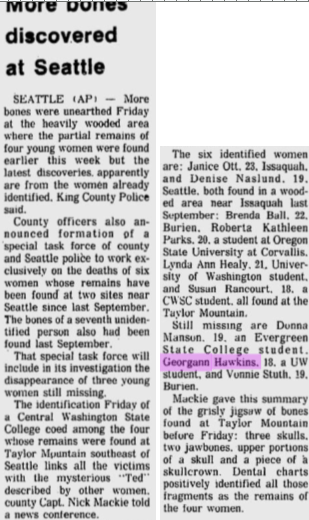

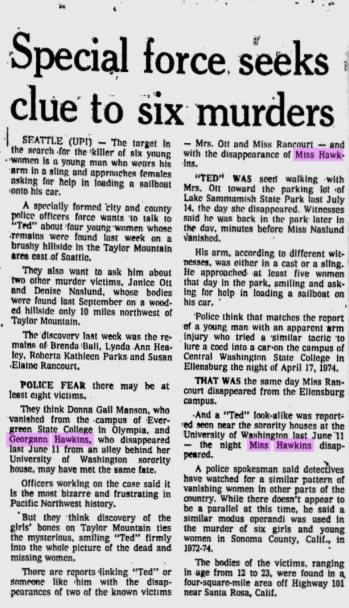

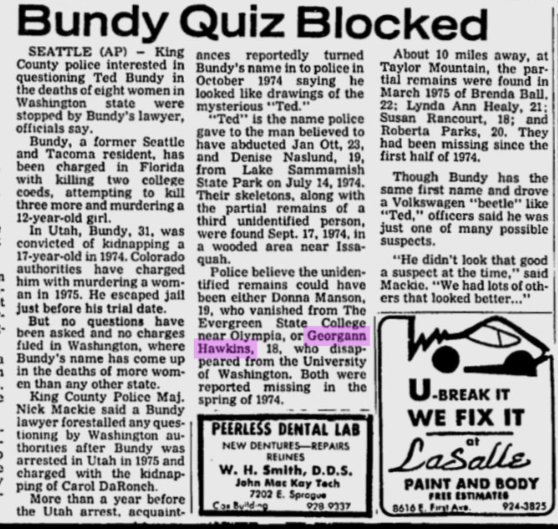

A newspaper article mentioning Georgann Hawkins published by The Spokane Chronicle on October 16, 1974.

The following quote from Bundy’s confession in 1989 confirms the location of this lot:

‘About halfway down the block I encountered her (Georgann) and asked her to help me carry the brief case, which she did. We walked back up the alley, across the street, turned right on the sidewalk in front of the fraternity house on the corner, rounded the corner to the left, going north on 47th. Well, midway in the block there used to be a… y’know… one of those parking lots they used to make out of burned-down houses in that area. The university would turn them into parking lots… instant parking lots. There was a parking lot there… (it had a) dirt surface, no lights, and my car was parked there.’

Residence of Lynda Ann Healy, 1974 vs. 2022.

Lynda Ann Healy’s House, 1974 vs 2022.

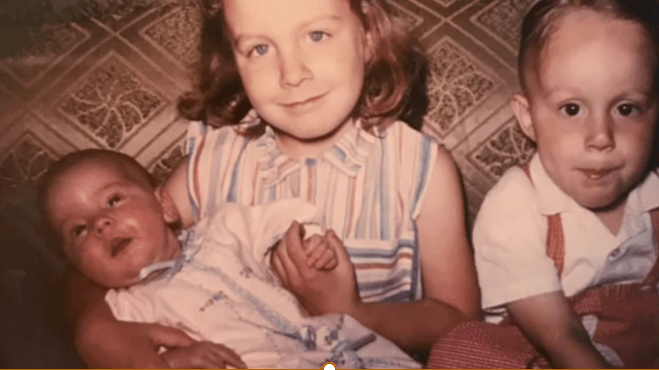

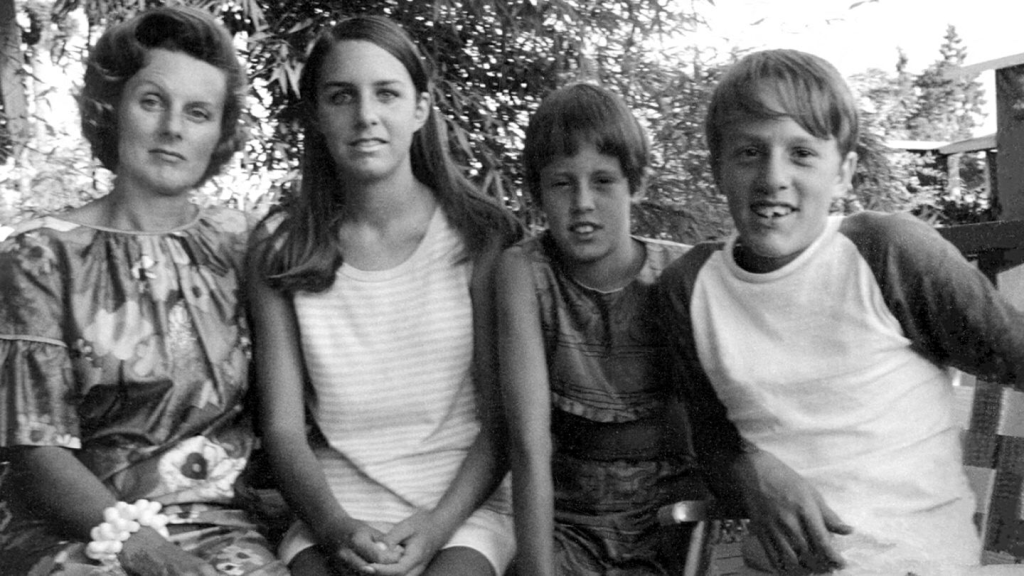

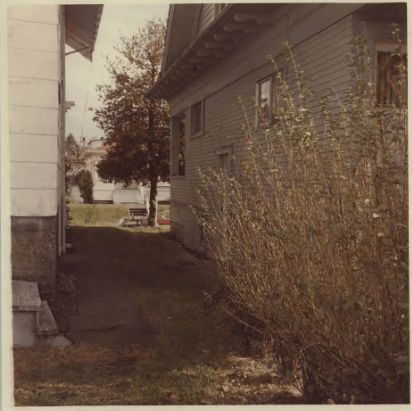

This is the residence where Ted Bundy attacked and abducted his first known murder victim, Lynda Ann Healy in February of 1974. Healy was born in 1952 to James and Joyce Healy and resided in an upper middle class Newport Hills neighborhood in Bellevue, Washington (a suburb of Seattle). The Healy’s had three children: Lynda was the oldest, then Laura, then youngest brother Robert. Lynda was a slender 115 pounds, with long brown hair, blue eyes, and a strong personality to compliment her kind nature. According to the book “The Only Living Witness,” by Hugh Aynesworth and Stephen Michaud, Lynda was 21 years old at the time of her murder and was a student at the University of Washington, majoring in Psychology. She also loved volunteering and working with children with disabilities. Lynda was an above average student who loved learning; she was also a talented musician and photographer, and was rarely seen without her camera.

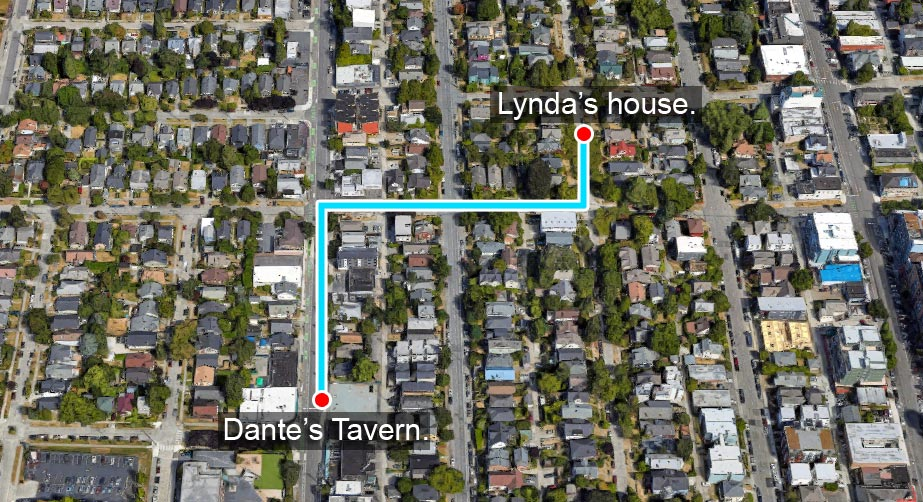

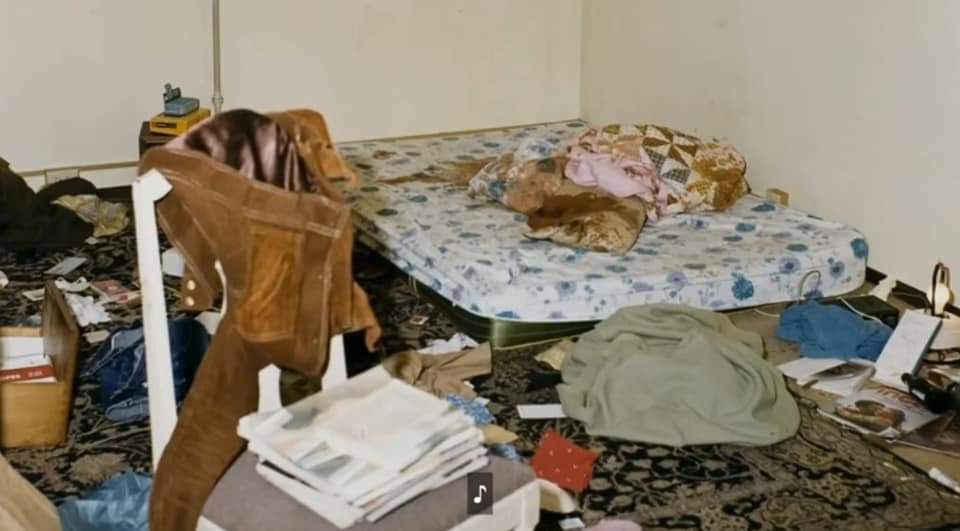

On Thursday, January 31st, 1974, Lynda borrowed her roommates car to go shopping for a family dinner she was preparing the next night and returned with her groceries at roughly 8:30 PM. Shortly after, Lynda and her roommates went drinking at a popular bar called Dante’s Tavern located at 5300 Roosevelt Way NE in Seattle. The bar was a five minute walk from Lynda’s apartment, and the friends ordered two pitchers of beer between the four of them; however they didn’t stay out too late because Lynda needed to be up at 5:30 AM to be at her job giving the ski report for a local radio station. A number of sources report that Bundy used to go to the bar often and it is hypothesized that he first saw Lynda there then followed her home. In the early morning hours of February 1, 1974, Bundy broke into Healy’s basement room. He beat her, took off her bloody nightgown (making sure to neatly hang it up in her closet), dressed her in blue jeans, a white blouse, and boots, then carried her off into the night, never to be seen again. It is theorized that Bundy only took clothes to make it appear as if Lynda left on her own, and we’ll most likely never know the truth.

A few hours later, Lynda’s alarm clock went off at 5:30 AM and continued to buzz for another half hour until her roommate Karen Skavlem woke up. Upon inspection, Karen could see that the room was completely normal and nothing looked out of place, so she turned off Lynda’s alarm clock and left.

Later that day, Lynda’s boss called the house asking where she was: his model employee didn’t show up to the station that morning for work. It was at that point that the roommates started to become concerned that something could be wrong. When Lynda’s parents showed up for dinner that evening and were informed about their missing daughter Mrs. Healy immediately called the police.

During a search of the room, police noted that everything was extremely neat and tidy, including her bed being perfectly made, hospital corners and all. Lynda’s roommates found this incredibly strange, as she usually didn’t make her bed when she had to leave early for work. It wasn’t until after police lifted up the bedspread that they spotted blood on the pillow and parts of the bed sheets. The location of the blood on the upper part of Lynda’s bed and nightgown suggests that Bundy incapacitated her by hitting her over the head with a blunt object, most likely while she was sleeping. It is not known if Lynda was dead or alive when her attacker took her from the house. At this point in the investigation, it was very clear that something terrible had happened to Lynda Ann Healy.

For the next 13 months, Lynda’s case remained unsolved. Then, in March of 1975, two forestry students from the Green River Community College discovered her skull and mandible on Taylor Mountain, where Bundy frequently went hiking. During a search of the site, police discovered the partial remains of four women, including the mandible of Lynda Ann Healy. The police were able to confirm her identity by comparing the lower jaw bone to her dental records.

By now, the police were well aware that there was a sadistic killer targeting women in the Seattle area. It wasn’t until Theodore Robert Bundy was arrested in November of 1975 for the attempted kidnapping of Utah resident Carol DaRonch outside of a bookstore in a shopping mall that the pieces of the puzzle all came together and he became the chief suspect in Healy’s murder.