The second installment of case files related to the murder of Vonnie Stuth, courtesy of the King County Sheriff’s Department.

Vonnie Joyce Van Driel-Stuth, Case Files: Part Two.

The second installment of case files related to the murder of Vonnie Stuth, courtesy of the King County Sheriff’s Department.

The first installment of case files related to the murder of Vonnie Stuth, courtesy of the King County Sheriff’s Department.

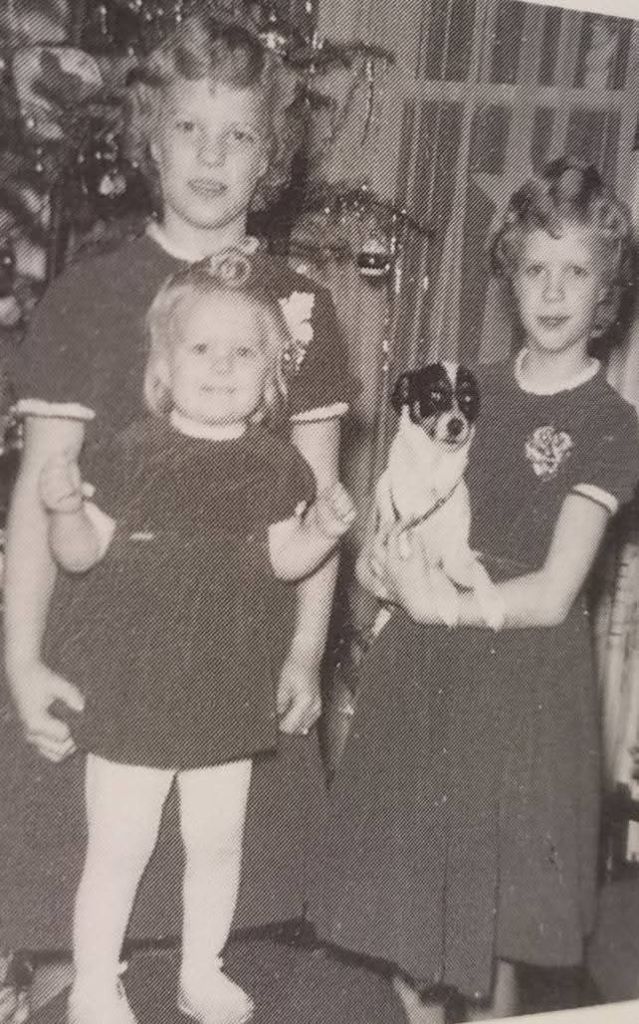

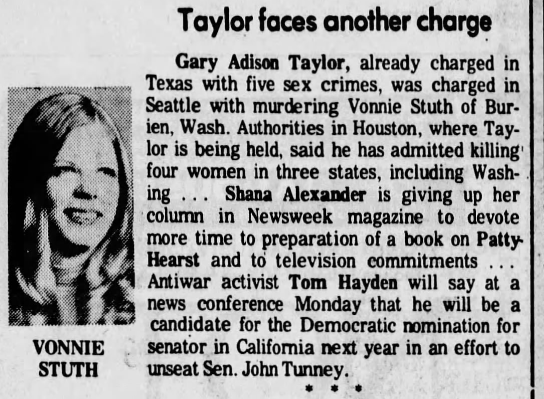

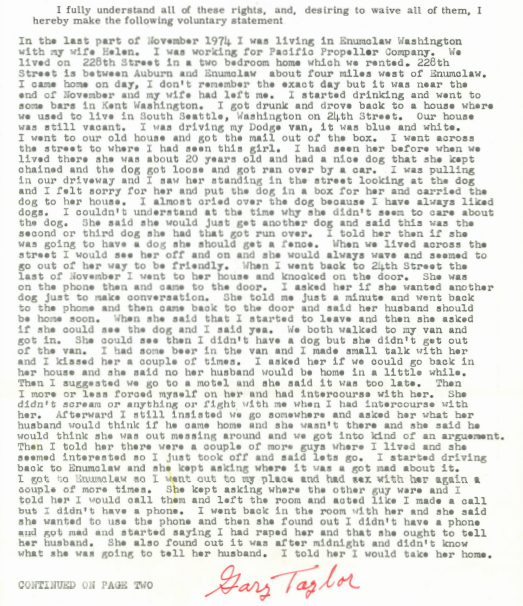

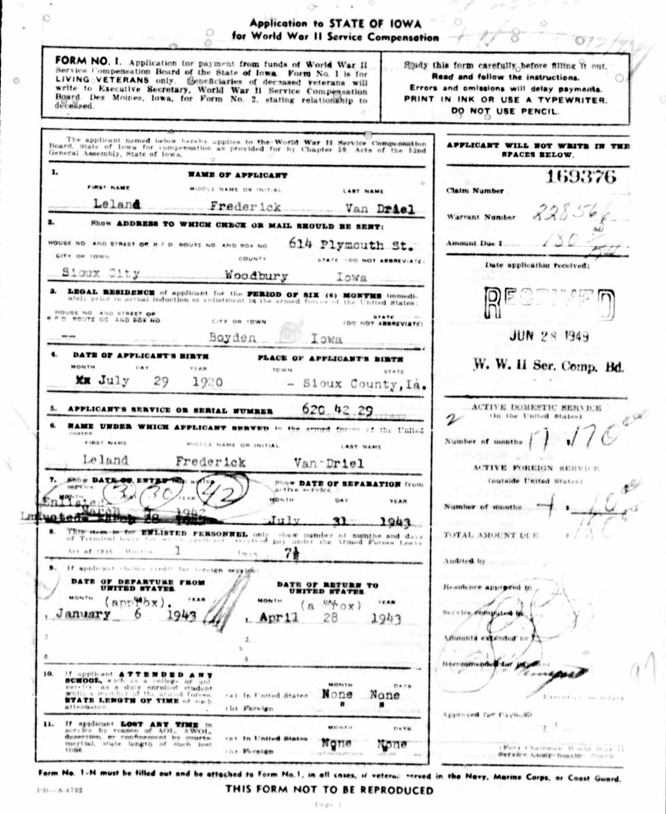

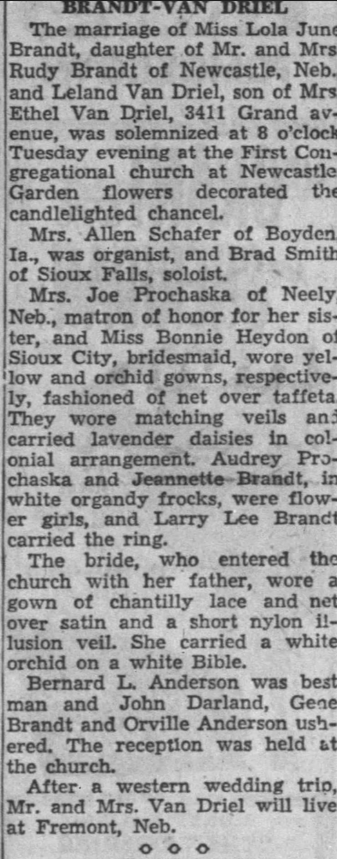

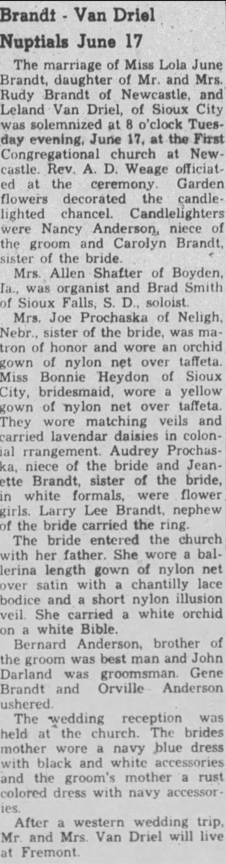

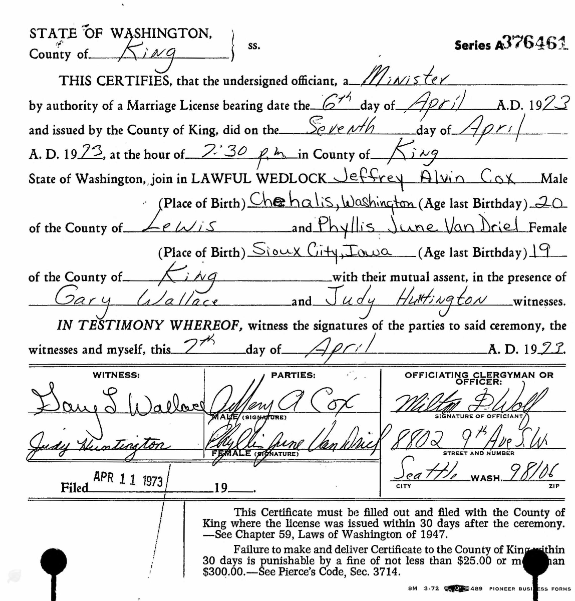

Vonnie Joyce Van Driel* was born on April 4, 1955 in Sioux City, Iowa to Leland and Lola (nee Brandt) Van Driel. Leland Fredrick Van Driel was born on July 29, 1920 in Sioux, Iowa, and Lola June Brandt was born on a farm in Nebraska on June 17, 1932. Leland was married once before Lola to a woman named Betty, and they divorced in May 1950 due to ‘cruel and inhumane treatment.’ The couple were married on June 17, 1952 and had four daughters together: Phyllis, Vonnie, Alicia, and Shirley. They relocated to Seattle when Leland got a job at Boeing, and Mrs. Van Driel was a stay at home wife and mother, and loved caring for her family. She filed for divorce in 1970, which was granted on June 6 and got married for a second time to Kenneth J. Linstad on June 19, 1972. * I have seen the family’s last name as VanDriel as well as Van Driel.

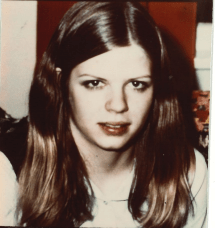

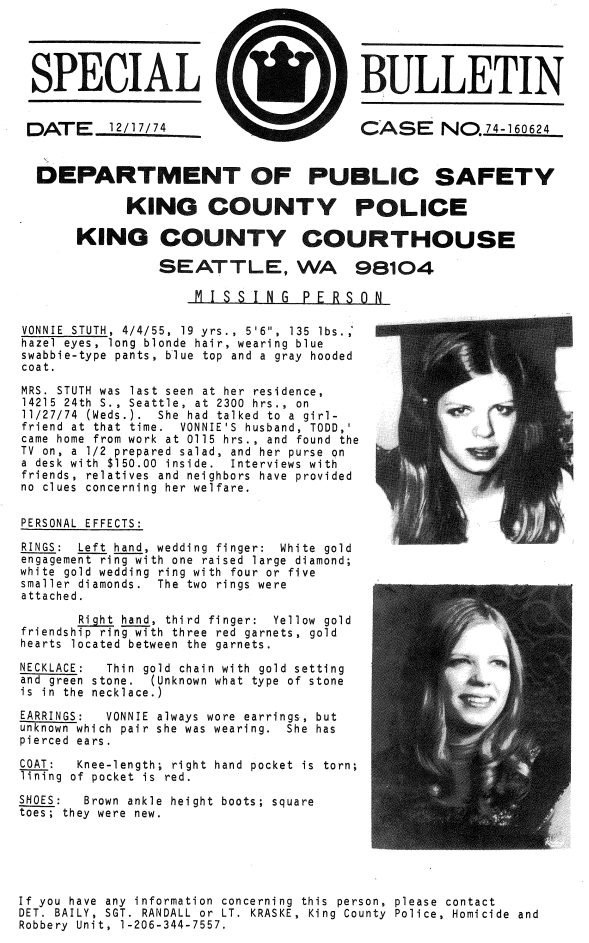

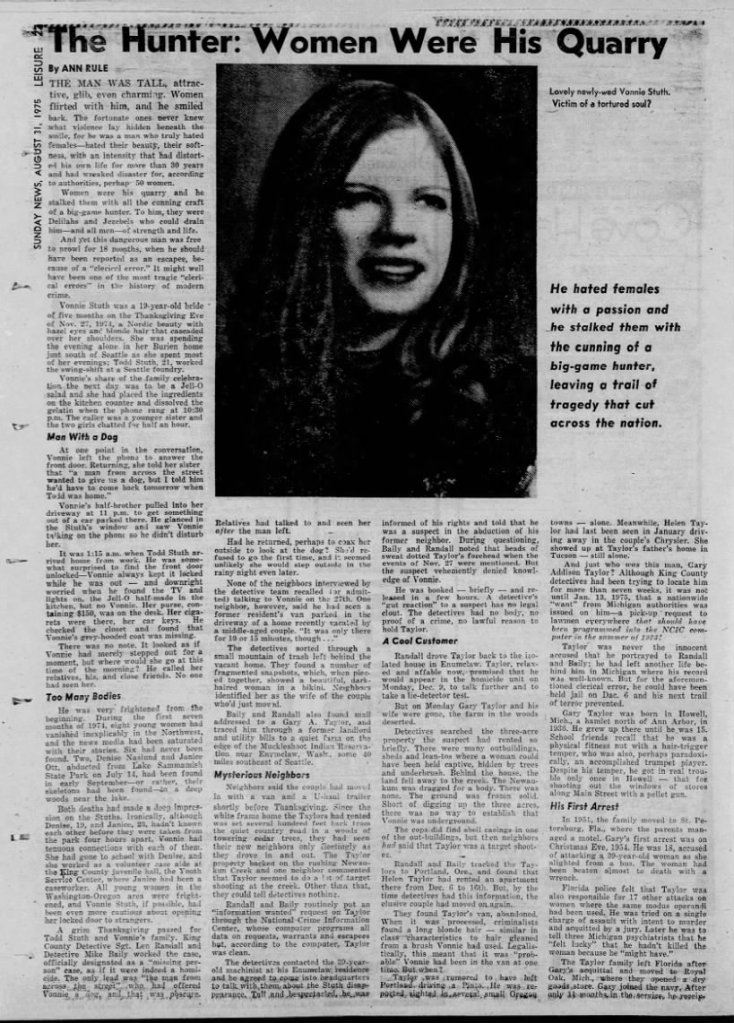

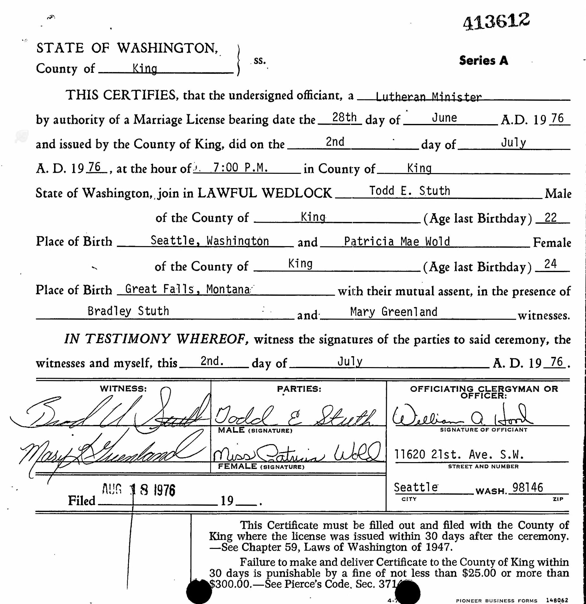

Vonnie graduated from Sealth High School in 1973, and married Todd Stuth on May 4, 1974; according to her marriage certificate, she was a housewife and volunteered at the Youth Service Center in Seattle. The newlyweds moved into a basement apartment located at 14215 24th Street South in Burien, which was roughly twenty miles away from the University of Washington. Todd Elliott Stuth was born on August 10, 1953 in Kent, WA, and graduated from Lincoln High School in 1971. At the time of his wife’s death he was a criminal law major at Highland Community College in Des Moines (which is the same school Brenda Ball attended before she dropped out), and worked the swing shift at Pacific Car & Foundry.

Late in the day on November 27, 1974 Vonnie kissed her husband goodbye in their Burien apartment and sent him off to work: twenty-one year old Todd began his day in the late afternoon and got home after midnight, and she had gotten used to spending her evenings alone. It was the evening before Thanksgiving, and the beautiful young newlywed told her family that her contribution that year was going to be a Jell-O salad, and she had just placed the ingredients on the kitchen counter and dissolved the package of gelatin when her thirteen year old sister Alicia called her at around 10:20/10:25 PM, and the two chatted for roughly a half hour.

Alicia said at one point during their chat, her sister put the phone down to answer a knock at the front door, and when she came back she said that ‘a man from across the street wanted to give us a dog (as they were moving), but I told him he’d have to come back tomorrow when Todd was home.’ Around 11 PM Vonnie’s half-brother stopped over to get something out of one of the family cars parked in the driveway: after looking in the window he saw she was on the phone, and since he knew what he needed and where it was he didn’t bother her.

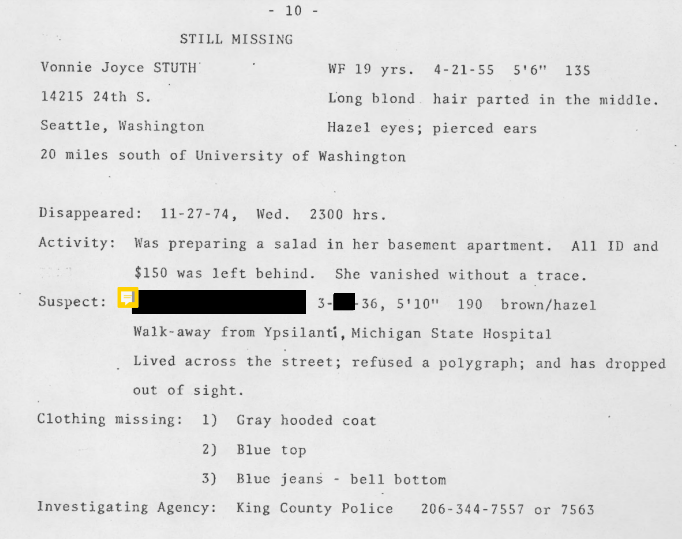

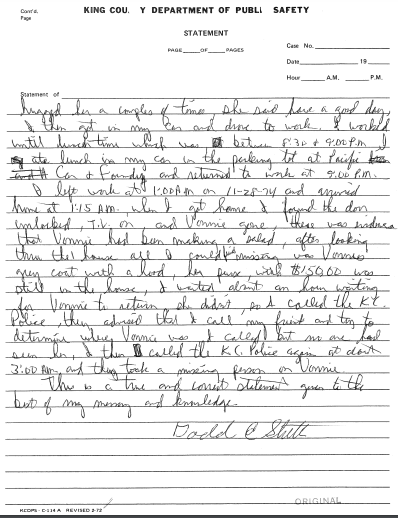

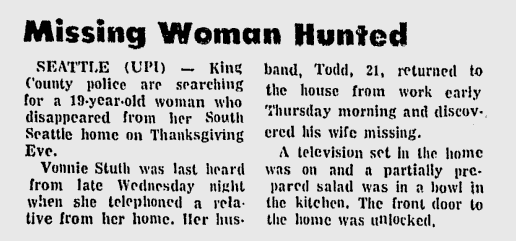

When Todd arrived home around 1:15 AM on November 28, 1974 he came home to an empty house: the front door was unlocked (which was unusual for his wife), the TV was on, and all of the ingredients for the Jello-O salad were left out on the kitchen counter. All of his wife’s belongings were present and accounted for, and her keys, drivers license, cigarettes, and $150 were found in her purse, which was left behind on the counter. Vonnie left no note, and missing from her wardrobe was a blue shirt, a pair of bell-bottoms, and her grey-hooded coat. Todd immediately started calling around to her family and friends, but they hadn’t heard from her; after an hour of waiting he called the King County Sheriff’s Department and tried to report her as missing, but was told by the dispatcher that he needed to wait the standard 48 hours until a missing person’s report could be filed.

The Van Driels/Stuth’s had a grim Thanksgiving with no news about Vonnie, and after the standard forty-eight hours passed Todd was finally able to file a report with the sheriff’s department. King County Detective Sergeant Len Randall and Detective Mike Baily almost immediately designated it as a ‘missing person’ case, and the only real lead they had to work with was ‘the man from across the street that had offered her a dog’ (and even that was vague).

Ted Bundy: In the early part of the investigation Vonnie was thought to be a victim of the mysterious ‘Ted of the Northwest,’ and she was often included in his list of Washington state victims: in the first seven months of 1974, eight young women had vanished in and around the Seattle area, and the news had been filled with their stories. At the time Stuth went missing in November 1974 Ted was living in his first SLC apartment and was a full-time law student at the University of Utah; he was still in a relationship with Elizabeth Kloepfer and the two were trying the long distance thing (despite the fact that he was unfaithful to her on multiple occasions). He was in between jobs at the time, as he left the Department of Emergency Services in Olympia on August 28, 1974 and remained unemployed until June of the following year when he got a position as the night manager of Bailiff Hall at the University of Utah (he was fired the next month for showing up drunk).

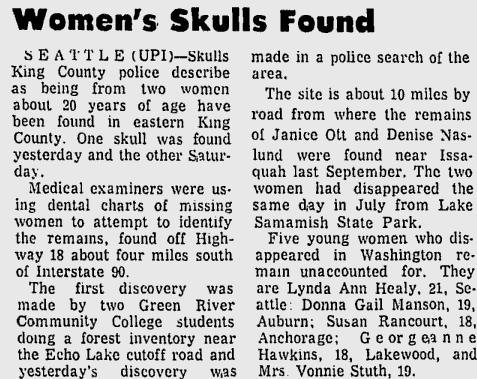

Over time, detectives were unable to establish any connection between Stuth and Bundy, and her case helped to highlight systemic flaws in the missing-persons reporting system at the time. Strangely enough, Vonnie had ties to both of Ted’s victims that were taken from Lake Sammamish State Park on July 14, 1974: Denise Naslund was in the same graduating class as her at Sealth High School, and she worked as a volunteer case aide in the Youth Service Center at the King County Juvenile Hall, where Janice Ott had been a caseworker.

After canvassing the neighborhood, the detectives quickly learned that the man with the dog had already moved Enumclaw, which makes the situation even more unusual since he no longer lived in the area. None of the Stuth’s neighbors recalled talking to Vonnie on the evening of November 27th, but one of them told investigators that he had seen a former resident’s 1972 Dodge van parked in the driveway of the home they had once rented, but ‘it was only there for 10 or 15 minutes.’

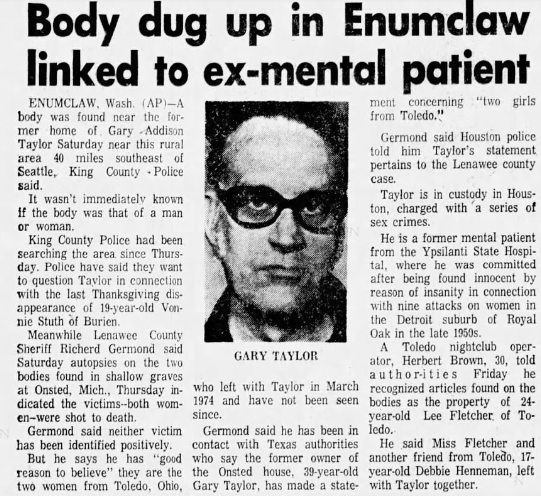

The detectives searched the abandoned home, and went through a ‘small mountain’ of trash that had been left behind by the former tenants and found a large number of torn up pictures; when reassembled one of them was of a beautiful, dark haired woman dressed in a bikini that one of the neighbors identified as Helen, who was half of the couple that had just moved out. The investigating officers also found mail addressed to a man named ‘Gary A. Taylor,’ and they were able to trace him through a former landlord and utility bills to a quiet farm on the edge of the Muckleshoot Indian Reservation, close to Enumclaw.

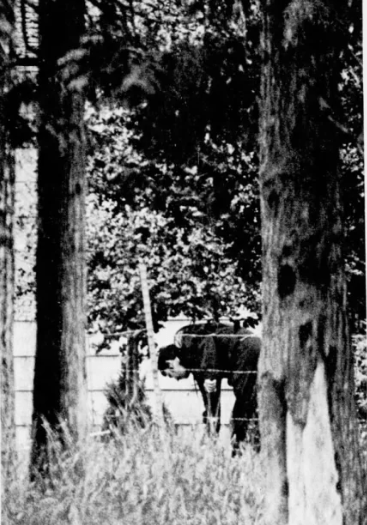

The Taylors’ new neighbors said the couple had moved into the white frame house with a van and U-Haul trailer shortly before Thanksgiving; the property was located next to the Newaukun Creek and one neighbor commented that Gary seemed to do a lot of target shooting aimed at the water, but other than that they could tell detectives nothing. Officers Randall and Baily put in a few ‘information wanted’ requests on Gary A. Taylor through the National Crime Information Center (whose computer programs all data on requests, warrants and escapees), but he came back clean and with no warrants.

Investigators were brought to a farm in Burien that had been rented by the Taylor’s after receiving reports of ‘unusual mounds of dirt’ found on the property, and according to a King County detective, ‘the story that we were probing for grave sites was possibly a misinterpretation by the media. Searching out there was just a long shot, but we had to check it out. The two earth mounds turned out to be a buried garbage pit and a stump.’

After Detectives Baily and Randall tracked them down, the Taylor’s were brought in for questioning, but they refused to answer any questions, and Gary denied ever knowing Vonnie. The officers got him a public defender and he was booked on December 6, 1974 but was released after a few hours, as their ‘gut feeling’ to a suspect’s guilt had no legal clout, and they had no body, no proof of a crime, and no lawful reason to hold Taylor. He promised King County Sheriff’s that he would come in on Monday, December 9, 1974 for another conversation (and a polygraph), but he never showed up.

After the Taylor’s skipped town detectives searched their residence and the surrounding property: there were many outbuildings, sheds, and lean-to’s where they could have left a body that were all hidden by trees and underbrush. Directly behind the house, the land fell away to the Newaukum Creek, which was immediately dragged for a body but with no luck, and because it was the middle of winter the ground was frozen solid, and short of digging up the entire three acres of property, there was no way to establish that any remains had been buried there; additionally, they found shell casings in one of the buildings next to the main house.

Detectives Randall and Baily tracked the Taylors to Portland and learned that Helen had rented an apartment in her name from December 6 to the 16th, but by the time they learned this, the couple had already left and their van was found abandoned. When the vehicle was processed for evidence, forensic experts found a long blonde hair much like Vonnie Stuth’s, which meant it was ‘probable’ she had been in the vehicle at one point in time… but when? It was rumored that Gary Taylor was to have left Portland driving a Ford Pinto, and he was also sighted in several small Oregon towns (alone).

Gary Addison Taylor was born in Howell, Michigan in March 1936, and childhood friends recall that he was a physical fitness enthusiast that had a hair-trigger temper, but was also an accomplished trumpet player. Despite his outbursts, he had no real juvenile criminal record aside from one incident in Howell when he shot out of the windows of stores along Main Street with a pellet gun. In 1951 when Gary was fifteen the family moved to St. Petersburg, where his parents managed a motel.

While in Florida, he was responsible for ‘the bus stop phantom attacks,’ where he bludgeoned about a dozen women at bus stops during the late 1940’s and early 1950’s; his standard MO involved loitering around bus terminals at night and waiting for someone that was alone to walk by, which was when he pounced and would attack them with a hammer. His first arrest took place at the age of eighteen on Christmas Eve in 1954 after he nearly beat a 39-year-old woman to death with a wrench as she got off of a bus.

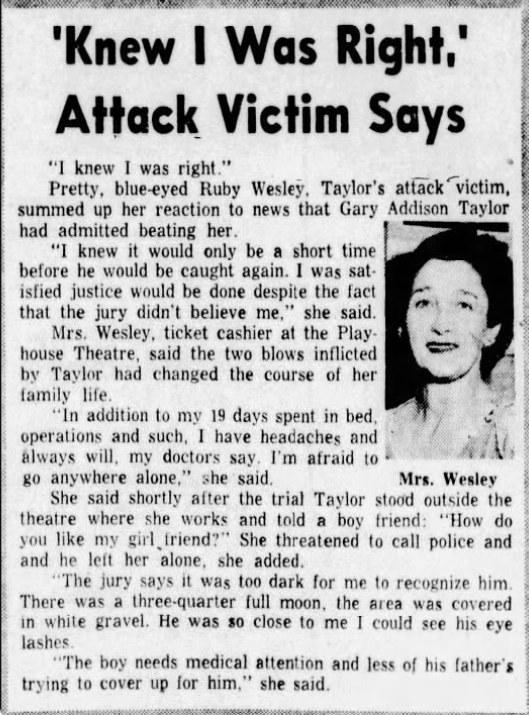

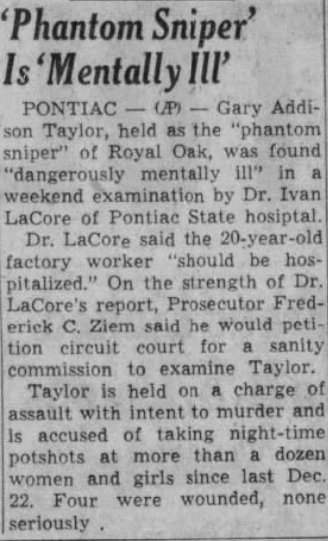

Despite investigators in the Sunshine State speculating that he was responsible for seventeen additional attacks on women where the same MO had been used, he was tried on a single assault charge with intent to kill but was acquitted by a jury; he later told three Michigan psychiatrists that he ‘felt lucky’ that he didn’t kill the woman, because he ‘might have.’ After their son’s acquittal the Taylors moved to Royal Oak, Michigan in 1951, where they opened a dry goods store and Gary joined the Navy… but it wasn’t long before he fell back into his old habits and began shooting women on the streets after dark. He was dubbed the ‘Royal Oak Sniper’ and shot sixteen women, but thankfully none of his victims were fatally wounded.

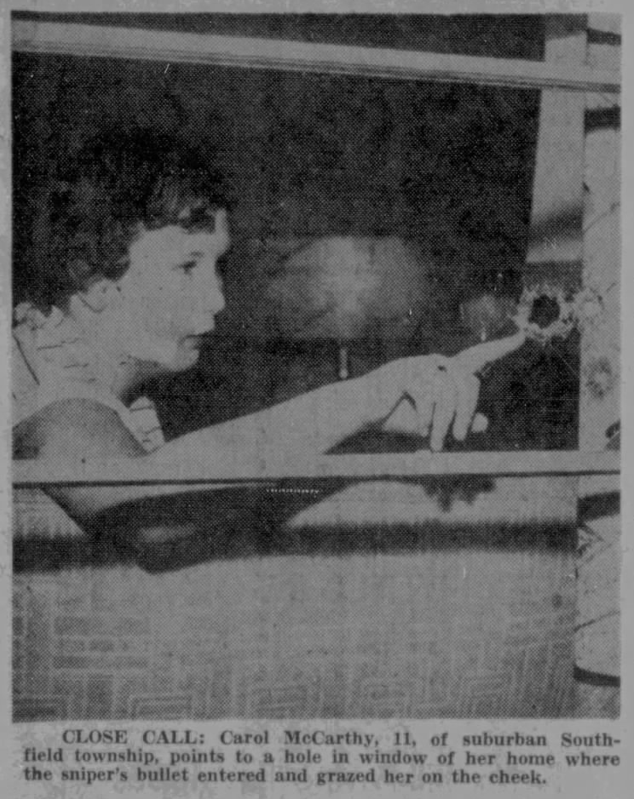

Two days before Christmas in 1956, Taylor shot and wounded a teenage girl in a drive-by attack in Royal Oak, and over the next few months he shot at several more females in a similar manner but thankfully missed every target. Several witnesses came forward and told police that the sniper was driving a two-toned black-and-white ’55 Chevrolet, and after they located the vehicle the suspect led them on a high-speed chase that ended in his arrest. Upon searching the car detectives discovered a .22 rifle, and Taylor couldn’t give them any particular explanation for his actions other than he wanted to shoot women and had these urges since he was a child, saying ‘it’s a sex drive compulsion.’

During Taylor’s trial, a psychiatrist testified that he was ‘unreasonably hostile toward women, and this makes it very possible that he might very well kill a person,’ and he was declared insane and was committed to Michigan’s Ionia State Hospital; three years later was transferred to the Lafayette Clinic in Detroit. While out on a work pass to attend a welding class, he talked his way into a woman’s home then raped and robbed her; the following year while out on another furlough he threatened a rooming-house manager and her daughter with an 18-inch butcher knife. He was not held responsible for either incident and was simply sent back to Ionia.

Even though he never stopped his violence against the opposite sex and had a self-proclaimed ‘compulsion to hurt women,’ Taylor was rated by prison staff as a ‘safe bet’ for out-patient treatment ‘as long as he reports in to receive medication.’ In 1970 he was transferred to an outpatient care facility after the director of the clinic determined that Taylor ‘was no longer mentally ill and would be dangerous only if he failed to take his medication,’ and drank alcohol.

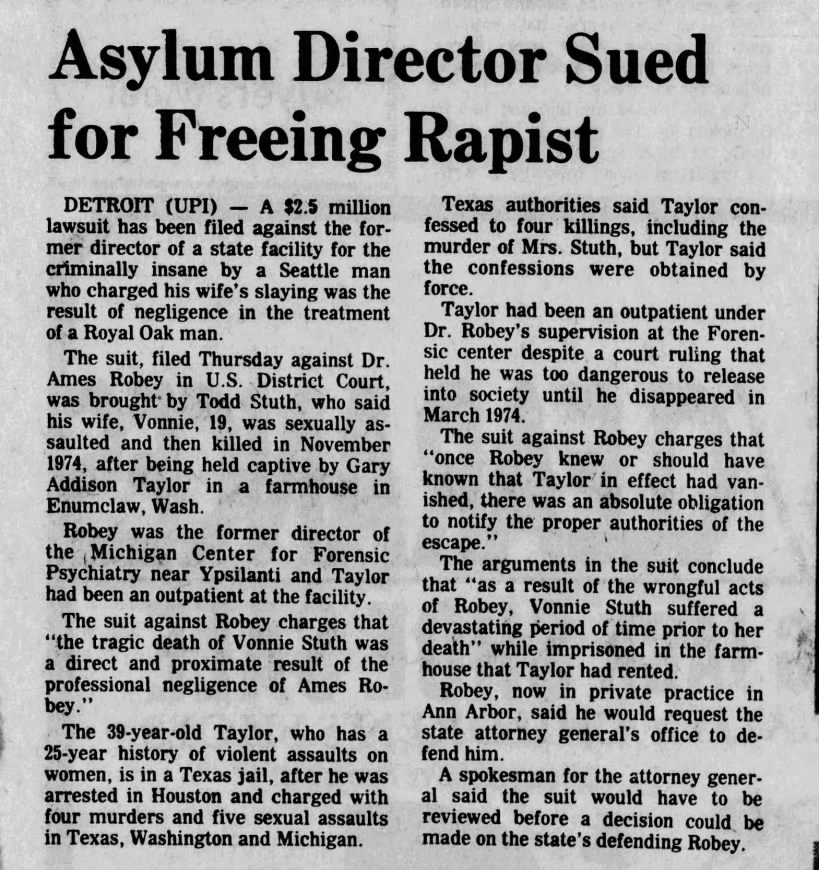

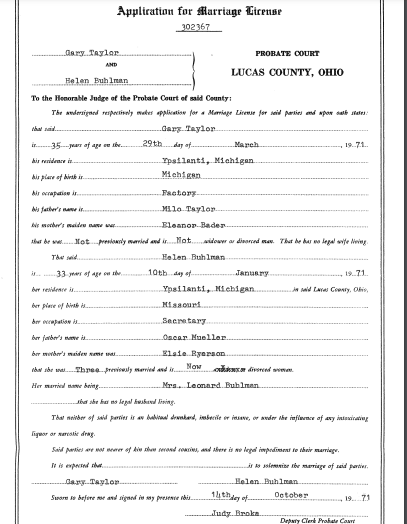

In 1972**, Taylor was released from the Michigan Center for Forensic Psychiatry in Ypsilanti thanks to a highly controversial state law: a person that had been acquitted of a crime by reason of insanity cannot be kept indefinitely in a mental institution and must be periodically declared mentally ill and deemed to be dangerous to himself or the community by a competent medical professional. Before his release, the center’s director Dr. Ames Robey diagnosed him with a character disorder (which is not a treatable mental illness), and felt that he was no longer dangerous as long as he was properly medicated and didn’t drink. Almost immediately after his release, Taylor married a secretary named Helen Buhlman, and the two moved first to Onsted, MI and later to the Seattle suburbs. **There may be some discrepancy as to exactly when he was released, as he was married on March 29, 1971 and another source said it was on November 3, 1973.

The state reported that in the two years after his release Taylor violated the conditions of his parole five times but was never recommitted by the Doctor, and after growing weary of reporting to treatment in late 1973 he completely stopped showing up altogether. When he failed to come in for scheduled check-in’s he wasn’t reported as an escaped mental patient for three months, and it wasn’t submitted into the national law enforcement communication system in Washington DC until January 13,1975. Plus, to make matters worse, when Michigan LE realized their mistake, the urgent bulletin they intended to release on November 6, 1974 never was and it slipped through the cracks.

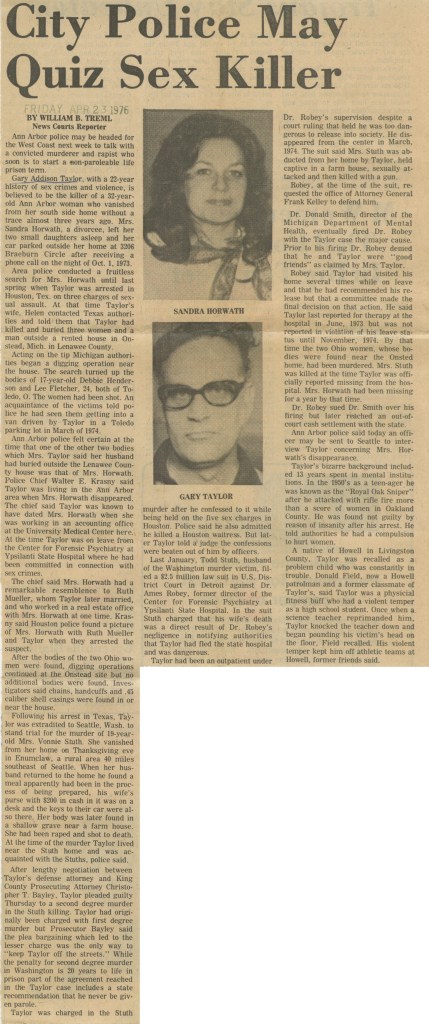

In December 1974 after separating from his wife, Taylor settled down in Houston, and Helen Taylor was last seen in January 1975 driving the couple’s Chrysler when she showed up at her FIL’s home in Tucson by herself. On May 20, 1975 Gary Addison Taylor was arrested in Houston for three counts of aggravated sexual abuse, one count of attempted aggravated rape, the rape of a 16-year-old pregnant girl, and the murder of a 21-year-old go-go dancer.

Discovery: According to an article published in The Times-Union on May 23, 1975, when news of her ex-husband’s arrest reached Helen (by that time she was in San Diego), she called Texas LE and told them that Gary had buried four bodies (three women and one man) underneath their bedroom window in a home they rented for three months in Michigan.

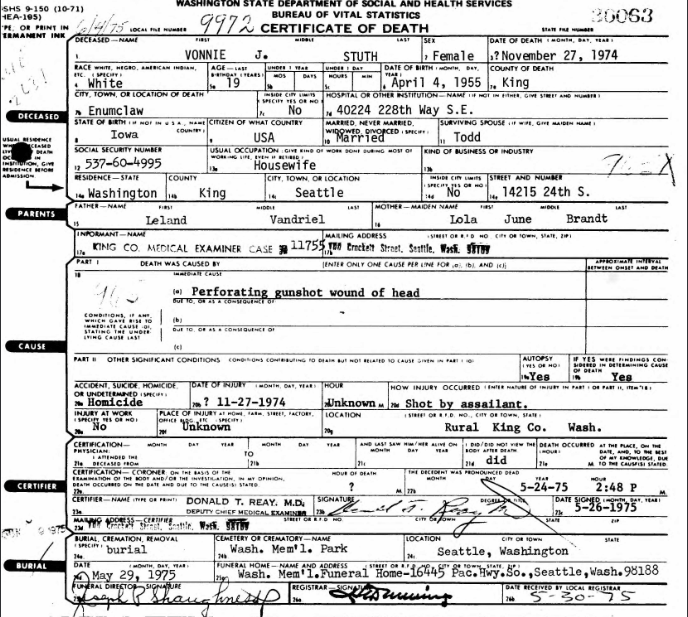

On May 18, 1975 the bodies of Vonnie Stuth and twenty-one year old Houston native Susan Jackson were found by detectives in a shallow grave along Neuwaukum Creek, roughly four to five miles northwest of Enumclaw; Stuth was ID’ed through dental records, and was still wearing the jeans, boots, and gray coat that were missing from her home the evening she disappeared. According to the King County ME, her exact cause of death is listed as a ‘perforating gunshot wound of the head,’ and detectives said she had been shot twice with a 9 mm pistol most likely during a desperate attempt to flee. They also said that due to the advanced level of decomposition it was impossible to tell if she had been sexually assaulted. Detectives said Jackson was last seen alive four days prior to the discovery leaving a Houston bar with Taylor, and her body had been bound with a dog leash and stuffed into a plastic garbage bag.

Tipped off by the Texas detectives, four days after the discovery of Stuth and Jackson investigators in Onsted discovered the remains of twenty-five year old Lee Fletcher and twenty-three year old Deborah Heneman from Toledo, wrapped in plastic bags, buried exactly where Helen said they were. After their discovery the remains were sent to the state police laboratory for analysis and autopsies were performed. Retired Sheriff Richard L. Germond said one of the victims was tied up with a piece of rope and the other had been bound with an electrical cord.

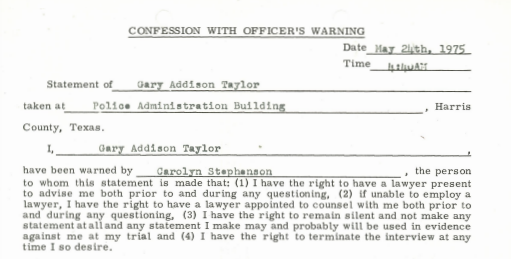

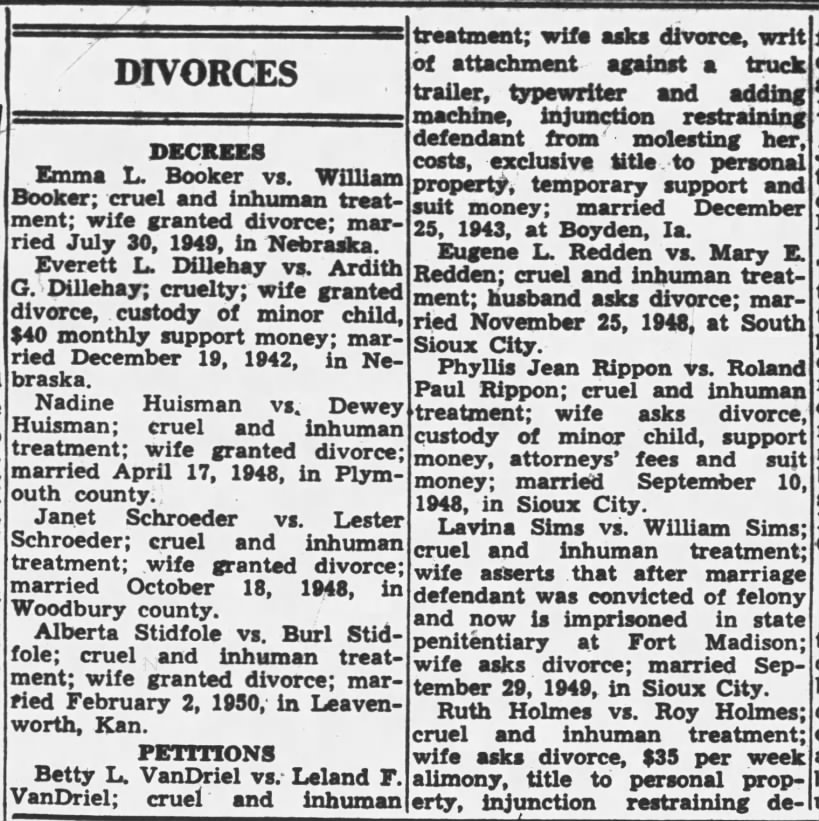

After his apprehension Taylor confessed to four murders (including Vonnie Stuth), however detectives were certain he wouldn’t have told them about any new women that they hadn’t already connected him to, meaning the actual number of his victims is unknown. After he admitted to killing Stuth, Taylor claimed that the detectives in Houston had beaten him into confessing and that there was no attorney present, which made the Texas and Michigan cases problematic. In an article published by The Daily News on August 31, 1975, Taylor was briefly a suspect in the death of Caryn Campbell (who wasn’t physically in Michigan when she disappeared but was from the state) and Julie Cunningham, who were both eventually tied to Ted Bundy. Further investigation cleared him of six additional murders in Washington state.

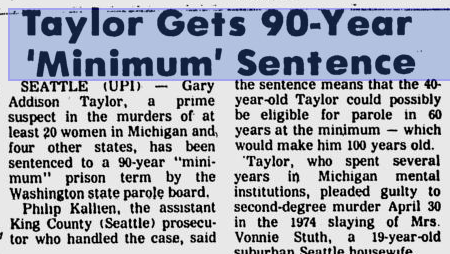

After his confession in Texas Taylor was extradited to Washington, where he was charged with first degree murder for the murder of Vonnie Stuth. On April 30, 1978 he pled guilty to second degree murder after an agreement was reached that both Texas and Michigan would not prosecute him for his crimes and he was sentenced to a ninety-year ‘minimum’ prison term by the Washington state parole board. Years after the conviction one of Vonnie’s sisters provided a victim impact statement to the Indeterminate Sentence Review Board, and Taylor’s parole was denied; his next parole date was set in 2035 when he will be 100 years old.

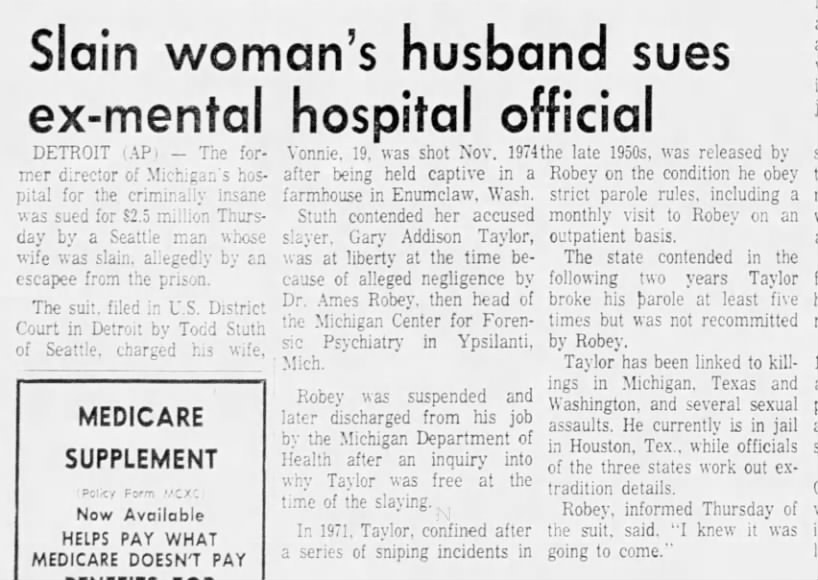

Todd Stuth: According to an article published in The Tri-City Herald on January 23, 1976, Vonnie’s widower Todd sued Gary Taylor’s former Psychiatrist Dr. Ames Robey for $2.5 million, as he was technically the one responsible for Taylor and he escaped under his watch. The former director of Michigan’s Center for Forensic Psychiatry, after the murders came to light Dr. Robey was suspended from his position and was eventually fired by the Michigan Department of Health after an inquiry into why his patient was free at the time of Stuth’s murder. In regard to the court case, Dr. Robey said in an interview: ‘I knew it was going to come.’

VSS/Victim Support Services: Lola ran a day care center out of her home and lived two blocks away from a woman named Linda Barker-Lowrance, and the two met when Linda needed someone to watch her kids when she went to PTA meetings. While waiting for answers as to what had happened to Vonnie, one evening when Linda arrived to pick up her children she said, ‘I am sorry my house is a mess but my daughter is missing.’ … ‘I wonder what the other mothers are doing?’

Despite over a fifteen year age gap between the two (and the fact that they hadn’t known each other for very long), Barker-Lowrance immediately responded, ‘let’s find out.’ The two women reached out to a Seattle-based newspaper reporter, who was able to give them phone numbers and addresses of several other families that had missing or murdered daughters and on February 25, 1975 thirteen families gathered in the social hall of a Catholic church in White Center. The group, officially dubbed ‘the Families and Friends of Violent Crime Victims***’ became one of the first victim advocacy groups in the US. *** It is now simply VSS.

Also a member of the group was Dr. Donald Blackburn, father of Bundy’s Lake Sammamish victim, Janice Ott. In a letter he wrote to President Ford about his daughter, Dr. Blackburn said that he had previously worked as a supervisor for the Board of Prison Terms and Paroles in Washington state, but ‘because of the relaxed supervision and control policies which were coming into effect, I left that service some sixteen years ago.’ President Ford wrote back saying he expressed concern about his daughter’s death and that he would try his hardest to push for reform.

Mrs. Linstad wrote to Bundy buddy Governor Daniel J. Evans in regards to the rights of a murder suspect, saying they ‘go on and on, that leads me to question the rights of the missing girls. There seems to be none.’ Lola’s baby now operates out of a two-story house on Colby Avenue and is staffed by eight full-time employees (including mental health professionals), and volunteers help to operate the crisis line after hours.

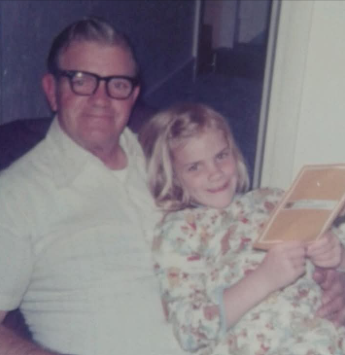

Mr. Van Driel died at the age of sixty-five on July 29, 1985 in Seattle, and Vonnie’s mother Lola died on October 1, 2024 in Sweet Home, Oregon. According to her obituary, at the age of eighteen she enrolled in secretarial college and after she got married and started her family they packed up and relocated to Seattle. She did a lot of fund raising for an organization called ‘The Healing Garden’ at Samaritan Hospital in Lebanon, Oregon and volunteered with a local soup kitchen and FISH food distribution pantry. She also taught Sunday school for many years and was a PTA mother and a Girl Scout Leader.

Over the course of her life Lola had two careers: she worked as a licensed daycare provider for fifteen years and after her daughters grew up she took classes to update her skills and became a family court clerk at the King County courthouse in downtown Seattle. After retiring at the age of sixty-five, she moved to Oregon to be closer to her two daughters. Sadly while in her 80’s Lola lost her ability to walk and was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, Meniere’s disease (hearing loss), and glaucoma (vision loss), but despite these challenges, she was always good natured and lived to be ninety-two.

Phyllis Van Driel-Clem is married and currently resides in Friday Harbor, WA; she retired from Compass Health (which is a community-based, non-profit organization in Washington that provides a wide range of behavioral health related services) in 2017. Vonnie’s sister Shirley Byrd relocated to Oregon and earned her RN from Linn-Benton Community College in June 2002; she is a passionate advocate for those struggling with substance abuse. Vonnie’s youngest sister Alicia lives in Federal Way, WA with her husband, who she has been married to since 1986. Todd Stuth remarried and lives in Kent, WA; he is currently employed as a flight instructor at Crest Airpark.

Gary Taylor is currently 89 years old and is still incarcerated in the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. Michigan investigators strongly suspect that he is also responsible for the disappearance of thirty-three year old Ann Arbor mother of three Sandra Horwath, who vanished without a trace on October 1, 1973. In 2002 detectives went to the prison Taylor was housed at and tried to speak to him about Horwath, but he refused to answer any questions.

Works Cited:

Barber, Mike, ‘Serial killers prey on ‘the less dead.’ (February 19, 2003). The Seattle Post-Intelligencer Reporter.

Gore, Donna. (March 14, 2014). ‘Two Desperate Housewives, First Support Group.’ Taken August 27, 2025 from ‘herewomentalk.com’

Hefley, Diana. (April 18, 2015). ‘For 40 years, group has been there in darkest times for crime victims.’ Taken August 9, 2025 from heraldnet.com