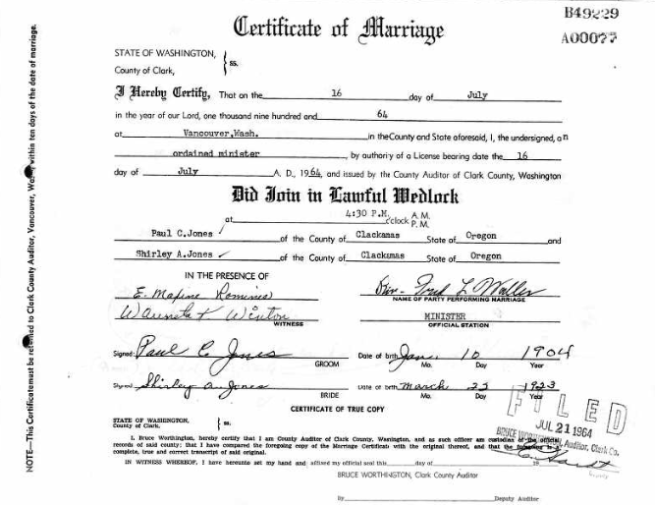

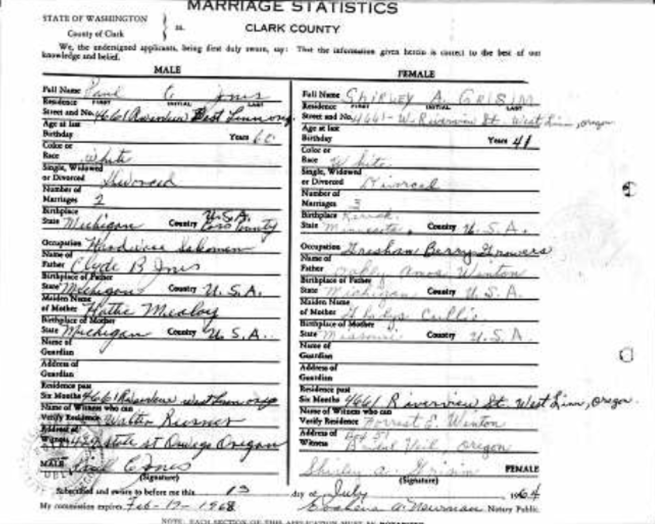

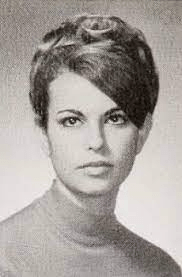

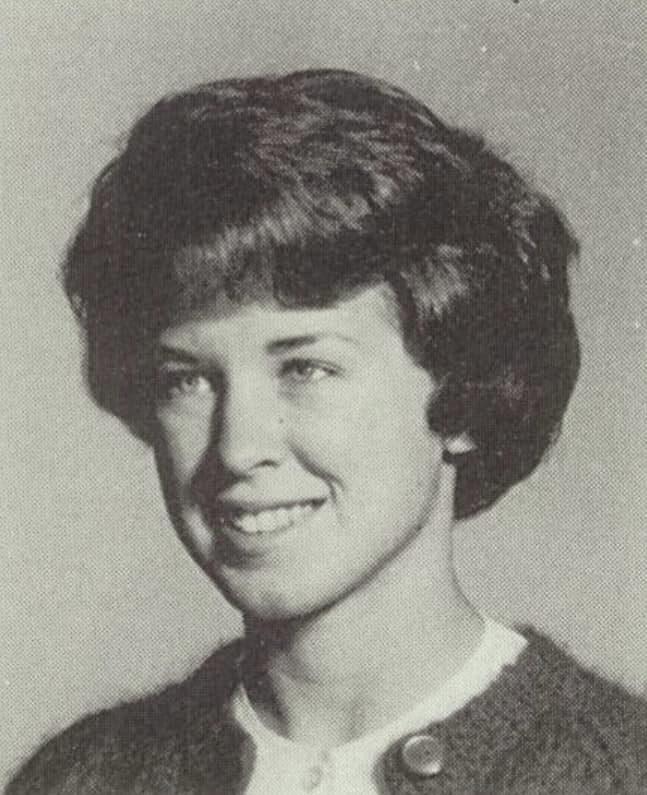

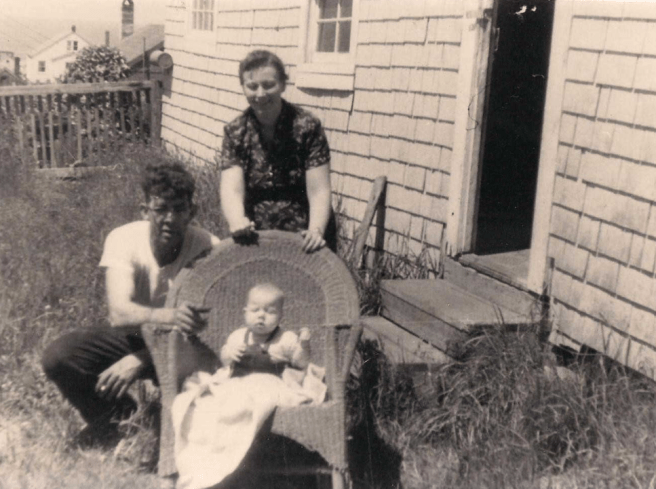

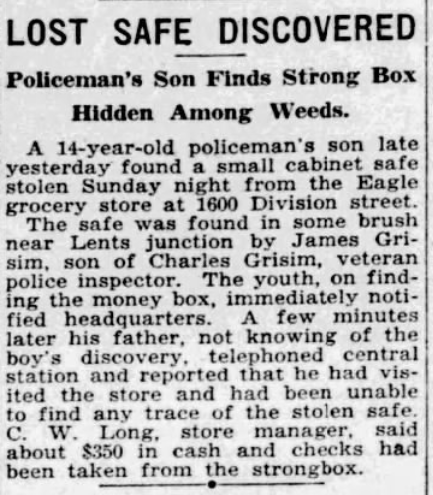

Background: Jamie Rochelle Grisim was born on November 11, 1955 in Newport, Oregon to James Raymond and Shirley (nee Winton) Grisim. James Raymond Grisim was born on December 13, 1913 in Portland, OR and Shirley Althea Winton was born on March 22, 1923 in Duluth, Minnesota; the couple were married on November 23, 1957 and had at least four children together, including Jamie and her younger sister, Starr (b. December 1956). While doing my research into Ms. Grisim’s background I came into quite a bit of conflicting information regarding her parents (largely her father), so instead of ‘publishing’ a whole bunch of incorrect details like I’ve done in the past, I’m going to leave it all out. I know that Starr is very (VERY) involved in her sister’s case, and I don’t want anything incorrect out there tainting Jamie’s case.

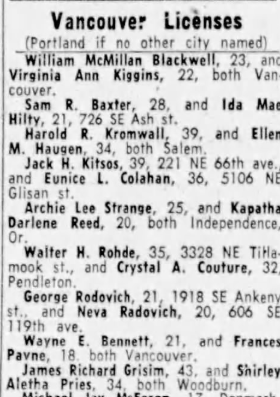

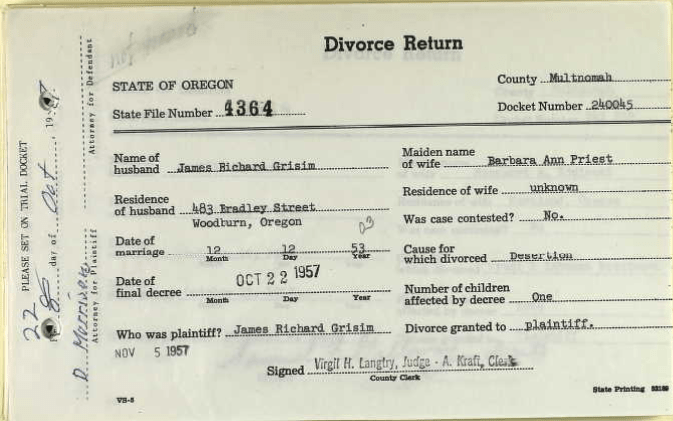

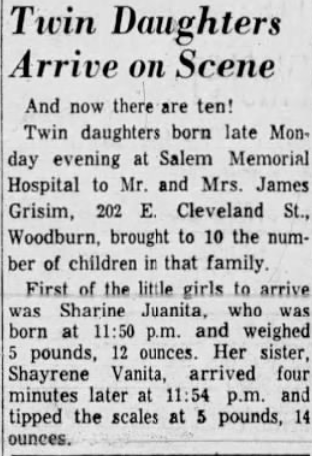

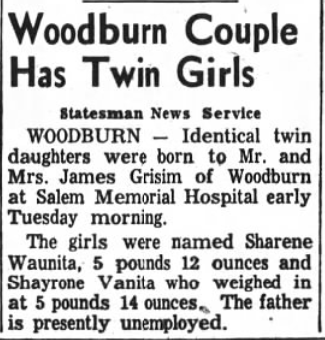

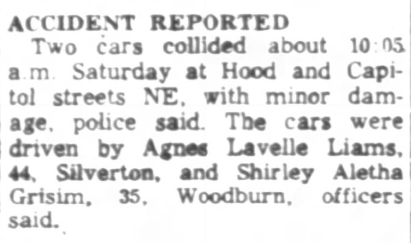

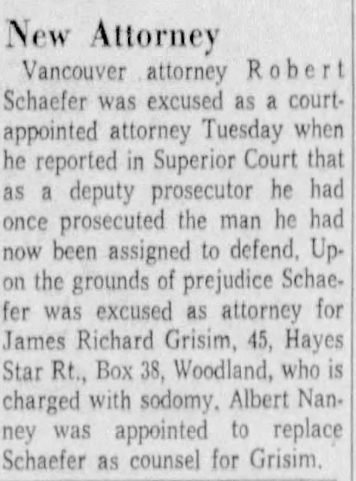

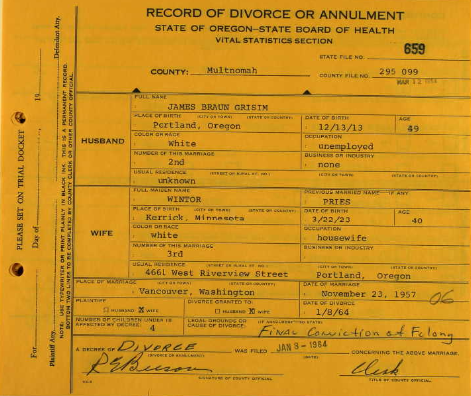

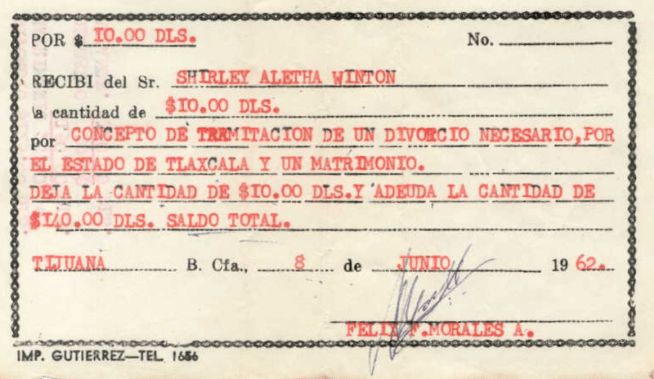

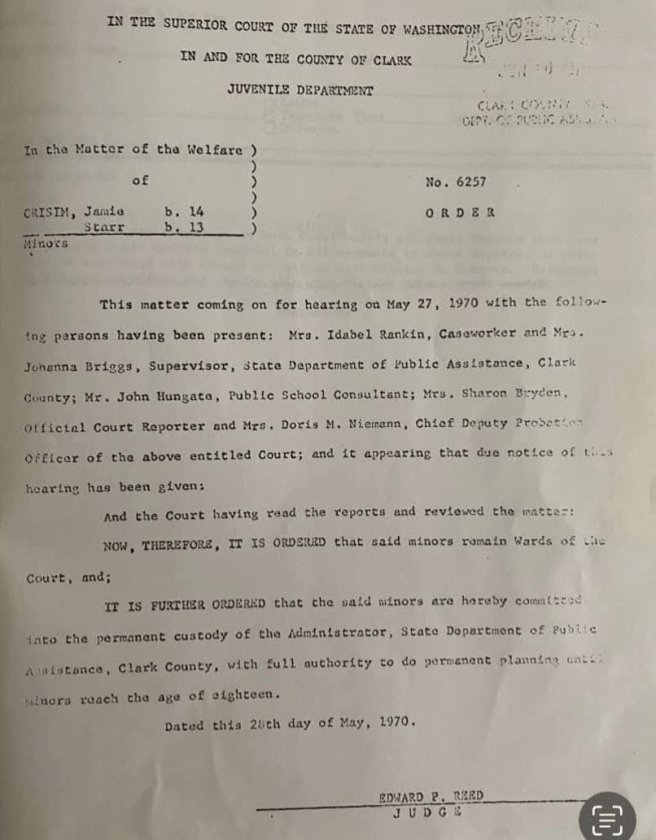

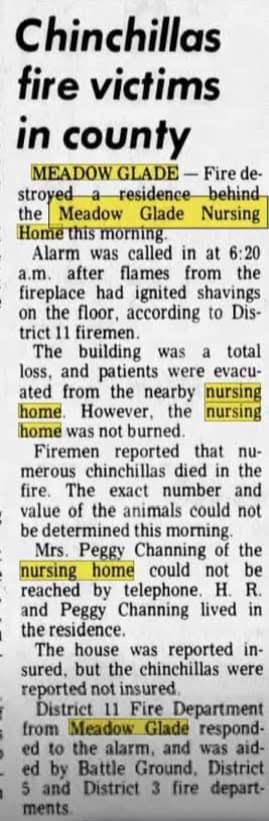

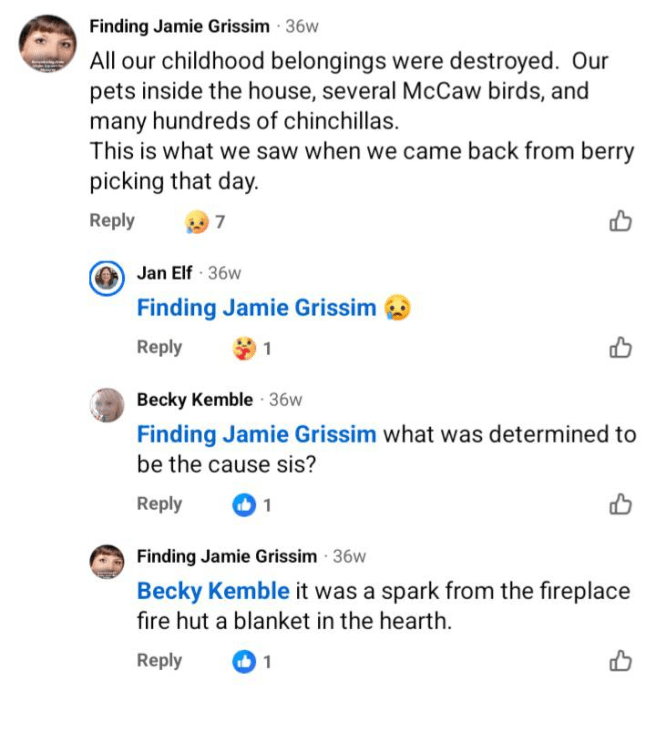

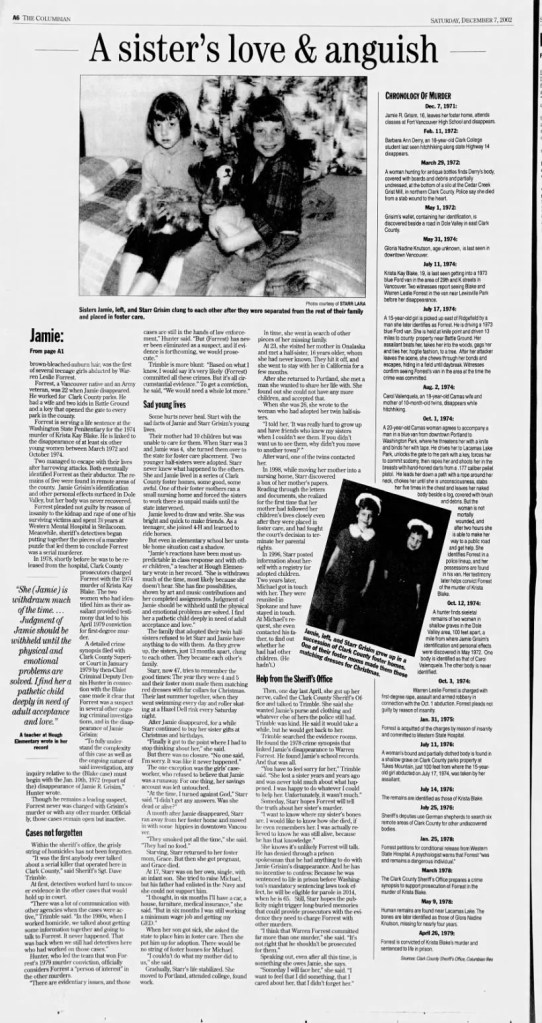

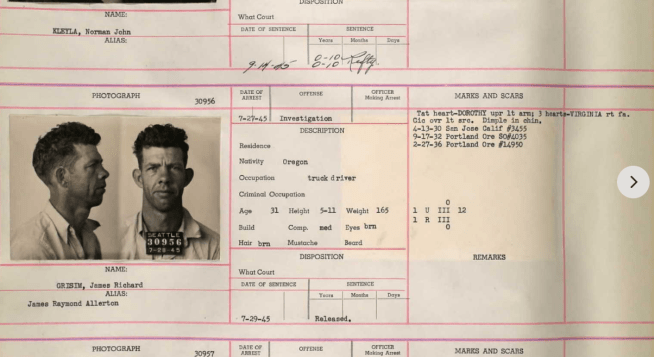

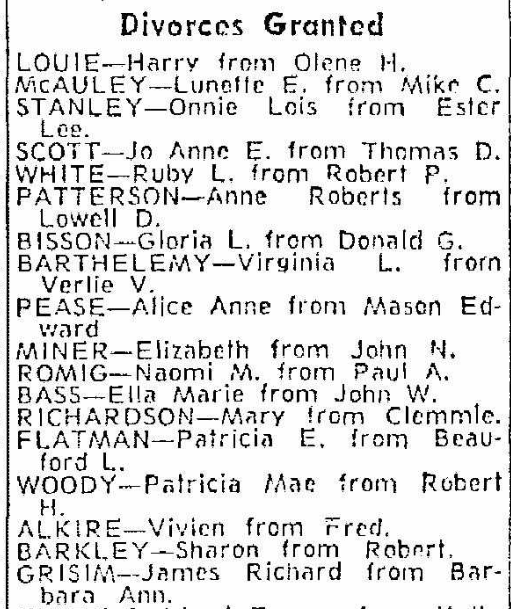

I am (largely) positive that Mr. Grisim worked as a truck driver at some point during his life, and according to some records I found on Ancestry he spent some time incarcerated; in addition to Shirley, he was also married to Barbara Ann Priest, Wintor Pries, Elizabeth Blanche Spangler, and Ruth Frederika Spoo, who he wed on June 24, 1986 in Multnomah, OR and remained with until his death. Jamie’s mother married Hans F. Pries in 1976 and had a total of ten children over the course of her life, however she was unable to care for them and when Jamie was only four years old, she was turned over to the state of Washington. Along with Starr, they were placed in foster care and two of their younger half-sisters were adopted; it’s unsure what happened to the other siblings. The girls lived in a series of Clark County foster homes, some good, some bad, some abysmal… one of their guardians ran a small nursing home and forced the sisters to work there as unpaid maids until the state removed them from her care.

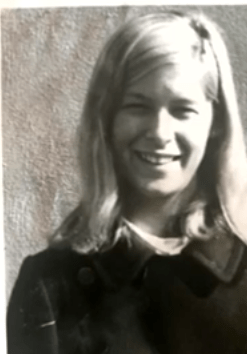

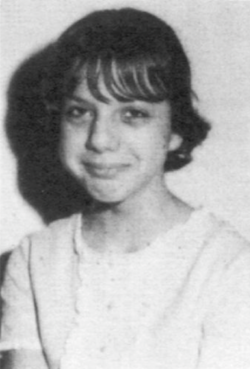

The girls loved the cinematic masterpiece ‘The Wizard of Oz,’ and they made a habit of watching it together at least once a year. Jamie was an enthusiastic member of her local 4H Club and she loved to ride horses and chew on lemons (lemon pie was her favorite); she also loved to draw and write. According to her Starr, her big sister was ‘fearless and artistic,’ and even though she was mostly happy and was quick to make friends, beginning in elementary school her home life had become unstable, which had started to cast a shadow across her life: one of Jamie’s teachers at Hough Elementary had written in her permanent record that her ‘reactions have been most unpredictable in class response and with other children. She is withdrawn much of the time, most likely because she doesn’t hear. She has fine possibilities, shown by art and music contributions and her completed assignments. Judgment of Jamie should be withheld until the physical and emotional problems are solved. I find her a pathetic child deeply in need of adult acceptance and love.’

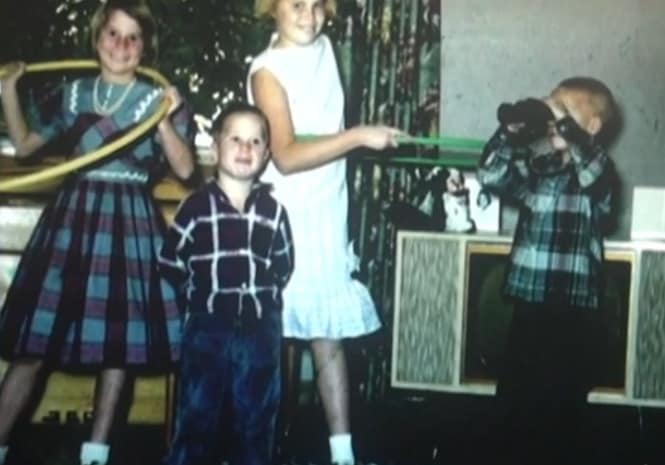

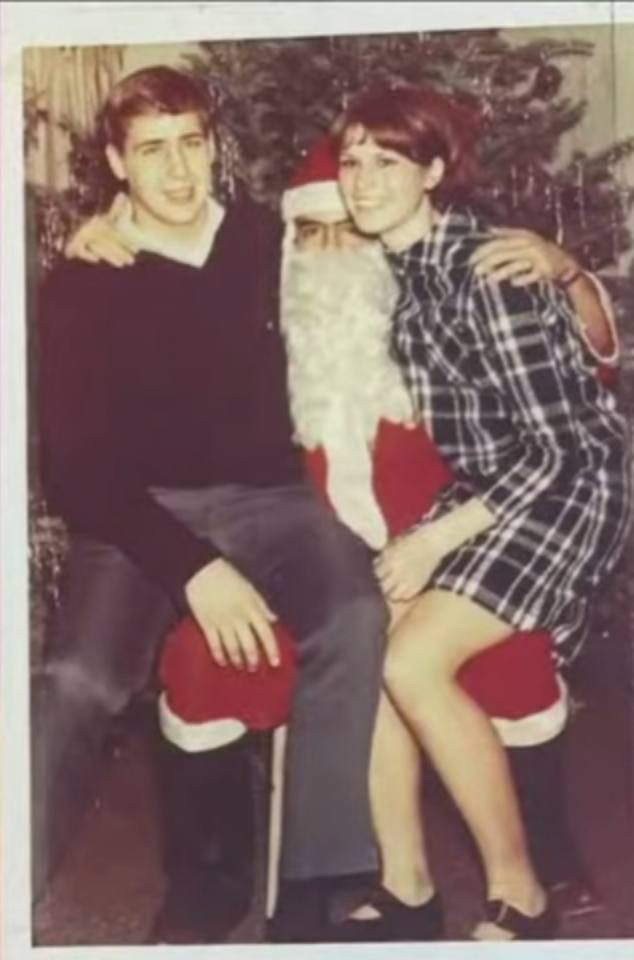

The family that adopted their twin half-sisters refused to let Starr and Jamie have any contact with them, and as they grew up the girls (who were only thirteen months apart) clung to each other and became each other’s family. When Jamie was five and Starr was four, their foster mother (at the time) made them matching red dresses with fur collars for Christmas, and during their last summer together they went swimming every day and went roller skating at a Hazel Dell rink every Saturday night. For a few years after she disappeared, Starr continued to buy her sister Christmas and birthday gifts, but she eventually ‘got to the point where I had to stop thinking about her,’ but she never had any closure: ‘no one said, I’m sorry. It was like it never happened.’

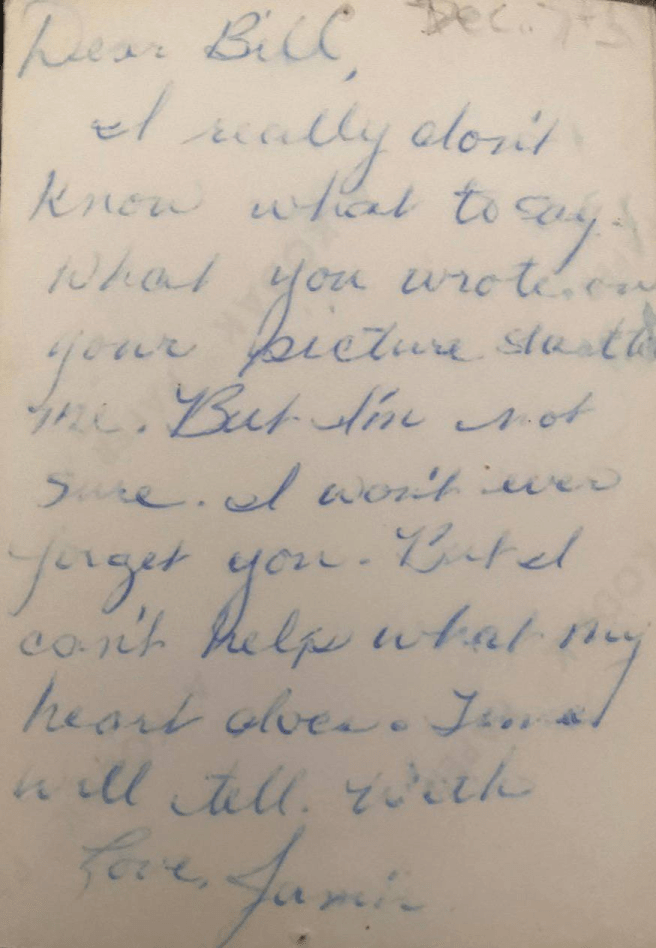

The sisters foster mother, Grace, had been a widow for ten years before they came into her life and she owned a small farm that had a garden, as well as cows, chicken, ducks, a dog, and a few cats. The girls favorite holiday was Thanksgiving, and Grace was a great cook, and Starr said every year she made homemade potato rolls, and: ‘we would eat like a whole pan by ourselves, they were so good. She also said that Jamie loved to draw faces and was especially skilled at putting on eyeliner: ‘I used to watch her, but I could never put on eyeliner like her. It was just like perfection.’ She also said her sister had ‘beautiful cursive writing,’ and read and wrote poetry in her free time. After school Starr said the two would often take the short walk to their friend Donna Ayer’s house to hang out, and the three quickly became close friends. According to Donna, ‘Jamie was always very outgoing, and bubbly. She had a really bubbly personality. And always seemed happy even though her circumstances might not have been. She was just a free spirit. I don’t think she let a lot bother her, and if she did, she didn’t show it. And she always protected her sister. They were very close.’

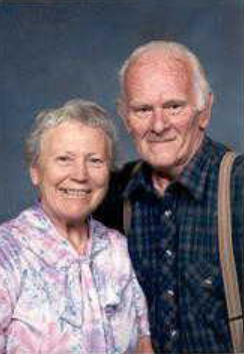

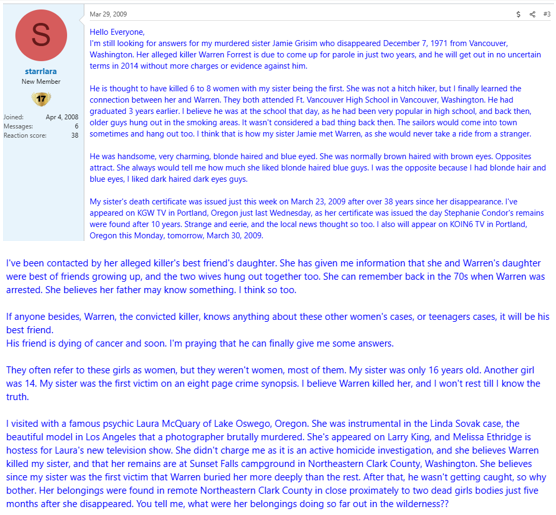

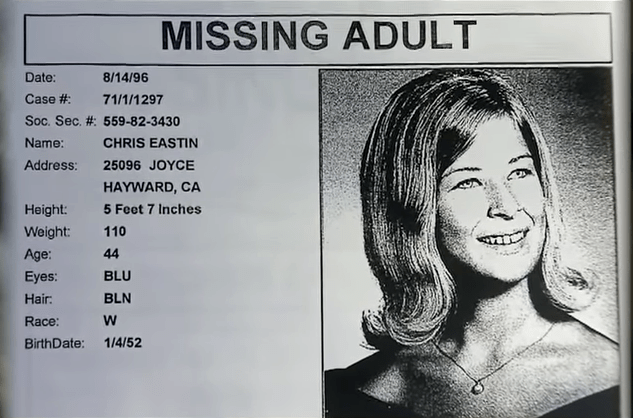

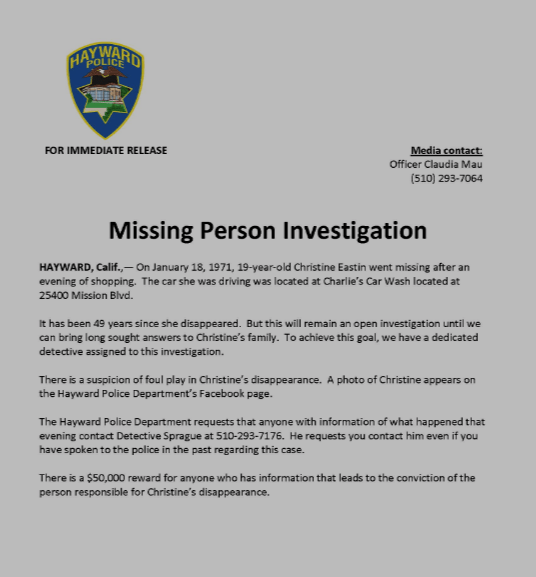

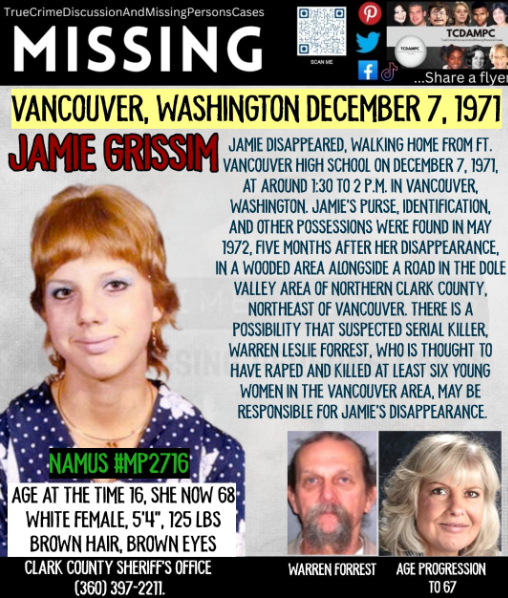

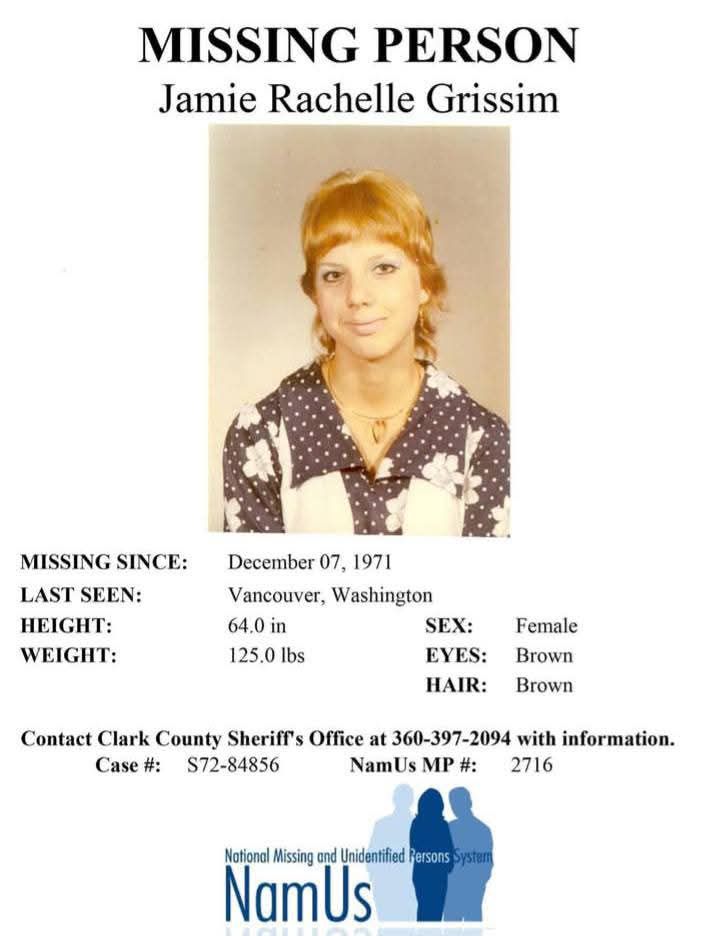

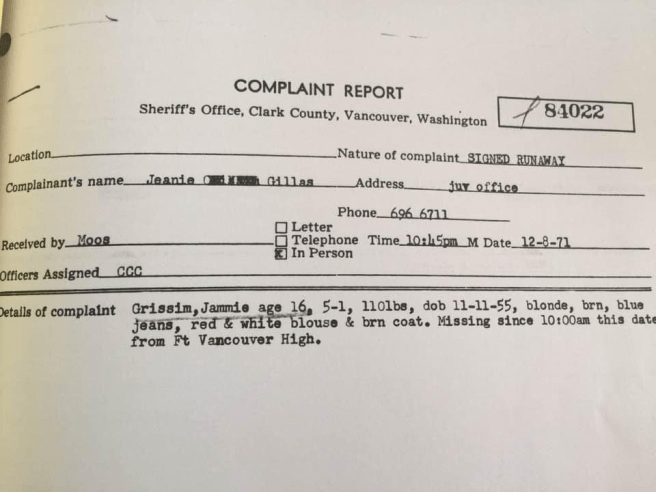

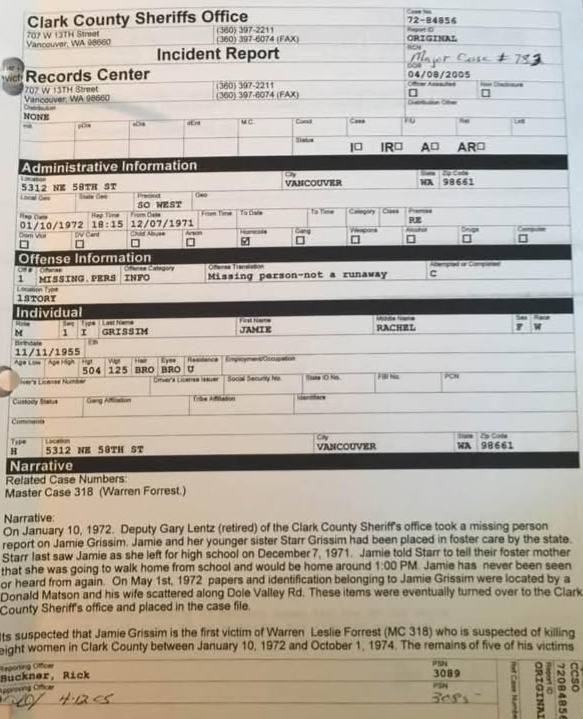

Disappearance: Sixteen-year-old Jamie was last seen on the afternoon of December 7, 1971 at approximately 1/1:30 PM walking home from Fort Vancouver High School in Vancouver, WA (as she had only two classes that day); she had told her foster mother she was going to walk home but she never showed up. When Starr got off the bus at 4:30, she immediately noticed that Jamie wasn’t around, and like so many of the other young women I’ve written about, police originally believed that she was a runaway. Her foster mother did report her as missing the following evening, but thirty days would pass by before an official missing persons report was filed. According to Starr, ‘it was really difficult. One day she was there, and the other she wasn’t.’

Nobody aside from her sister seemed overly concerned that Jamie had simply vanished without a trace, and the only exception was the girls’ case worker, who refused to believe that she had simply runaway: for one thing, her savings account was left untouched. Starr was only fourteen when she disappeared, and their foster mother told her that she had run away and ‘didn’t want anything to do with her ever again,’ and even though she never believed that (exactly), she also admitted she didn’t know what to believe. A month after Jamie disappeared, she ran away from her foster home and moved in with some hippies in downtown Vancouver that ‘smoked pot all the time and had no food.’

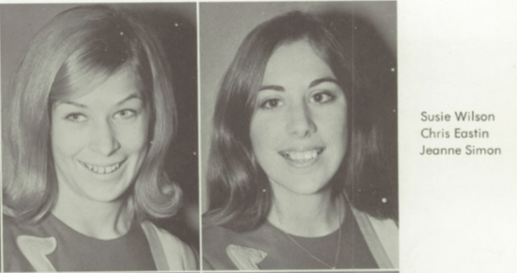

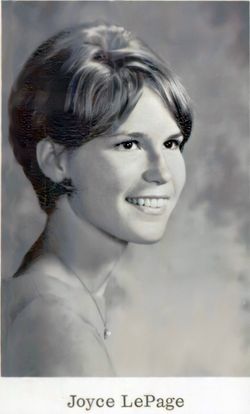

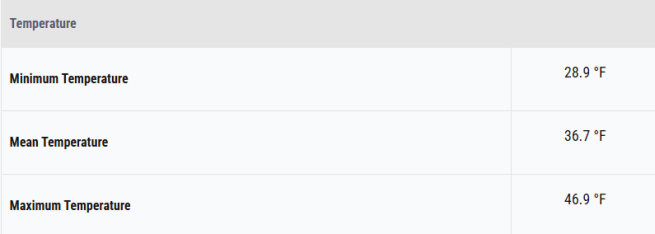

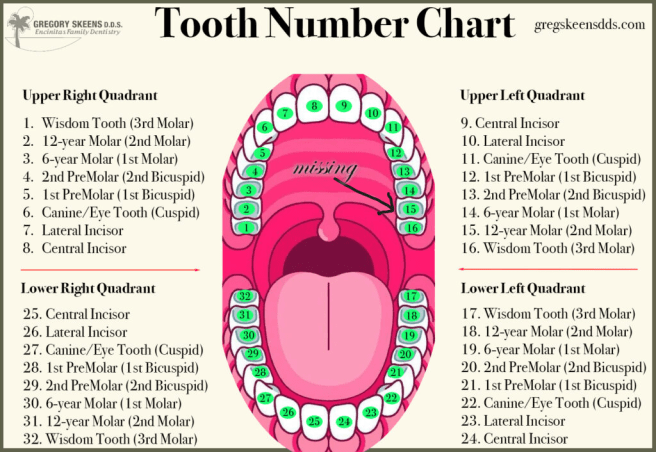

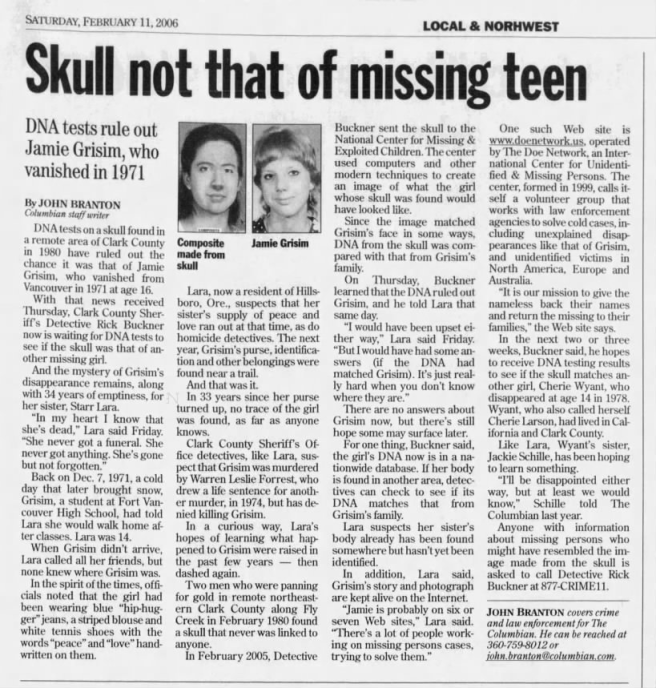

Investigation: Jamie stood between 5’4 and 5’5 tall and weighed around 125 pounds; she also wore glasses while reading. She had been last seen wearing blue ‘hip-hugger’ jeans, a red/white striped shirt with short puffy sleeves and rounded neck, and white tennis shoes that had ‘peace’ and ‘love’ written on them along with other little drawings; she also possibly had on a long brown corduroy coat as well as ‘dangling earrings’ (as her ears had been pierced). Grisim had brown hair that she had previously been bleached blonde (it was actually dyed a reddish hue at the time of disappearance), had brown eyes, and was missing her #15 tooth (which was a top back molar). She had hearing loss in one ear as well as dermatographia, which is a skin condition where light scratching or pressure results in raised red welts or hives to appear (the marks usually fade within thirty minutes). On the afternoon of December 7, 1971 the temperature had been very low in Vancouver, WA and it snowed the next day.

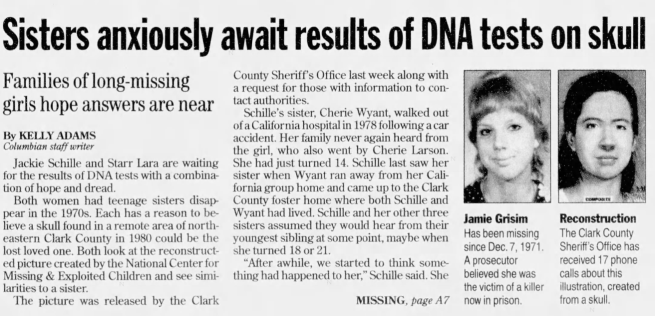

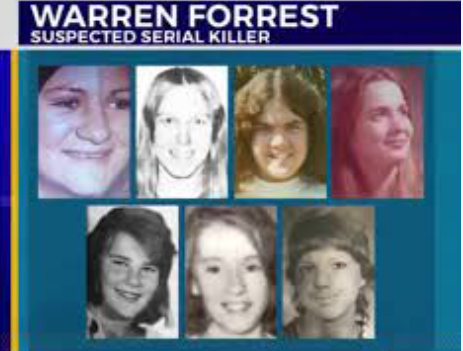

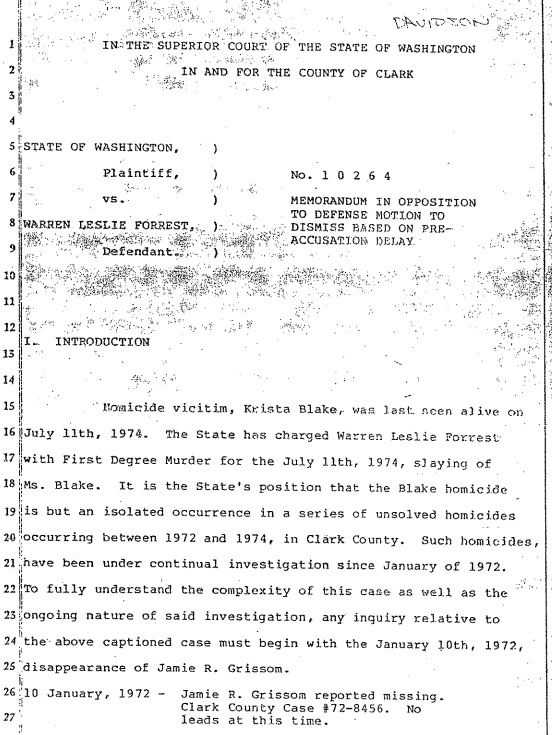

In the initial stages of the investigation authorities suspected Jamie was a runaway, however opinions shifted after a search for her remains in May 1972: detectives had discovered a number of her personal belongings, including her purse, identification, and some other small trinkets in the woods Northeast of Vancouver, at a bridge crossing close to a trail where two other victims of serial killer Warren Leslie Forrest were discovered. It was initially believed that she ran away from home and left the state, but that theory was quickly squashed as there were no confirmed sightings of her after she disappeared. Since Martha Morrison and Carol Valenzuela were both later located not far from where her possessions were found, authorities have reassessed their conclusions and now believed that Grisim was abducted and killed by Forrest.

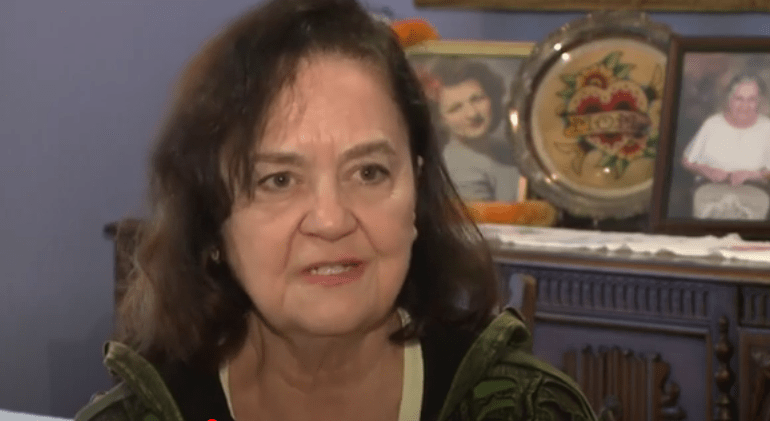

Seventeen years went by before Starr learned that detectives had found Jamie’s ID/possessions, and that in 1974 hunters had discovered the bodies of Morrison and Valenzuela in shallow graves a mile away from the Skamania County line, and it was at that moment she knew that she would never see her sister alive again: ‘I knew that day she was never coming back alive. I still hoped, and I still tried to find her. But deep down I knew I would never see her again. Because there was no way she would have been way out there like that. I believe that he was the last person to see her, and he holds all the answers. It bothers me that she’s not here and he knows what happened.’

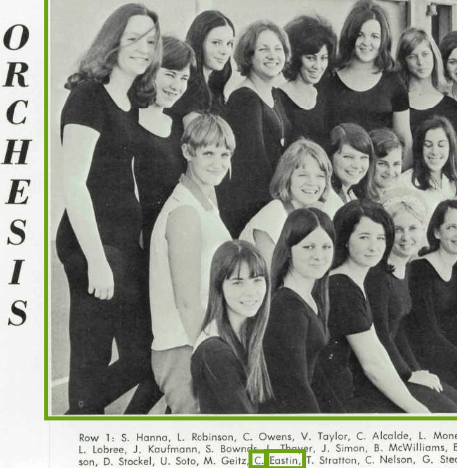

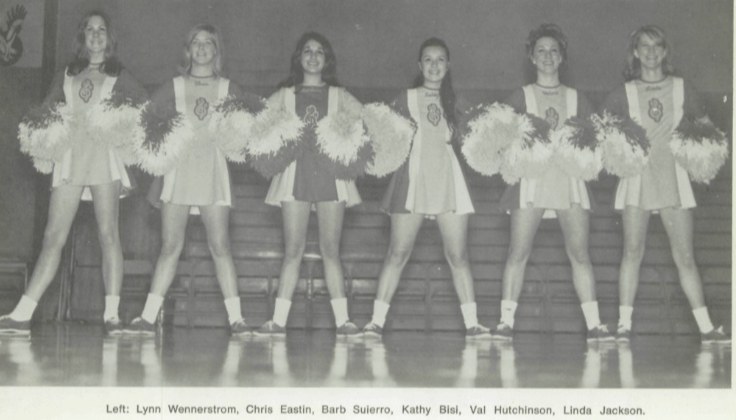

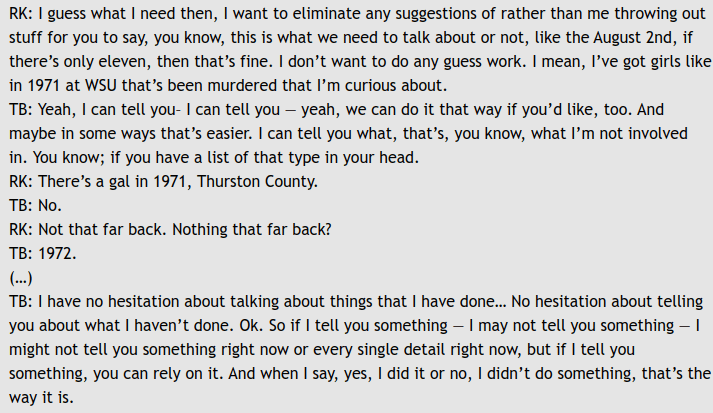

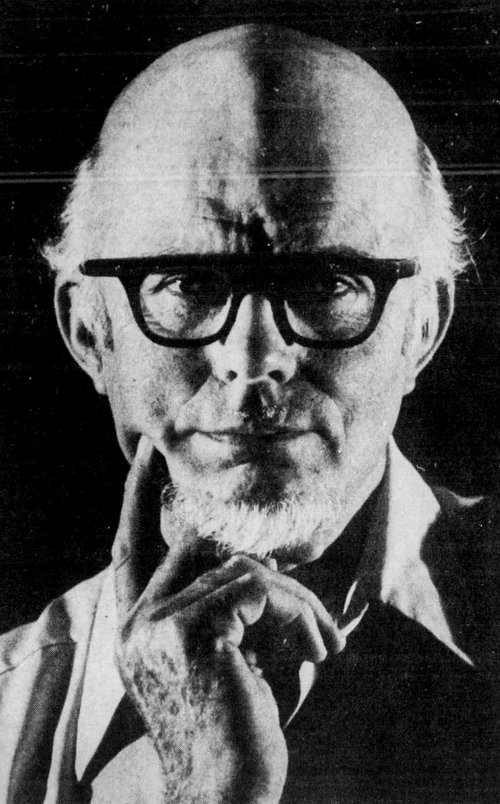

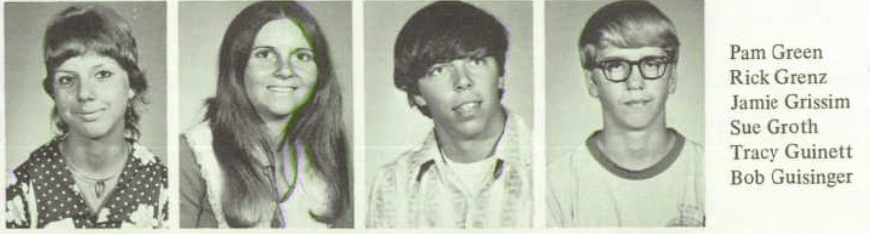

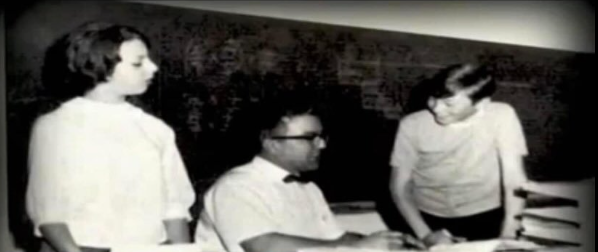

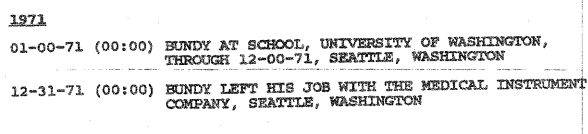

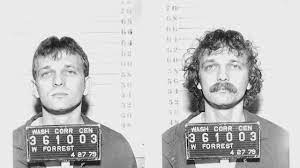

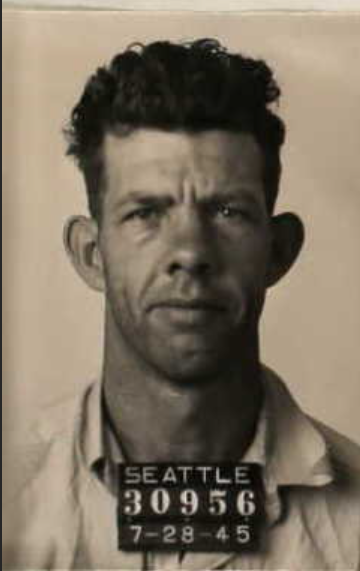

Warren Leslie Forrest: Jamie is strongly suspected to be the first victim of Warren Leslie Forrest, who was born on June 29, 1949 to Harold and Delores Forrest in Vancouver, WA; the youngest of three brothers, he attended Fort Vancouver High School (which coincidentally is the same one that Jamie was attending when she disappeared) and was on the track and field team (of which he eventually became the captain). After he graduated in September 1967, Forrest and his brother Marvin (b. 1948) were drafted into the Vietnam War, where he served in the Army as a fire control crewman for the 15th Field Artillery Regiment at the Homestead Air Force Base in Homestead, Florida.

After he was discharged from the service, Forrest returned to Washington state in August 1969 and married his high school sweetheart, Sharon Ann Hart. The couple had two children together and relocated from Florida to Fort Bliss, Texas then to Newport Beach, California, where he enrolled at the North American School of Conservation and Ecology; his academic career didn’t last long, and he dropped out at the end of the first term. In late 1970, the Forrest family moved to Battle Ground, WA when he found employment with the Clark County Parks Department.

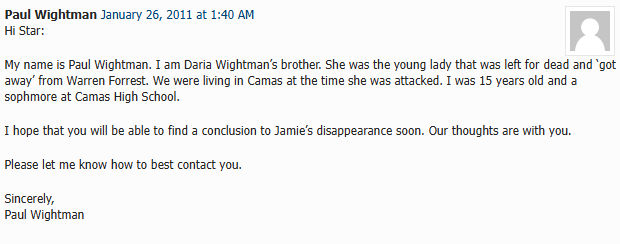

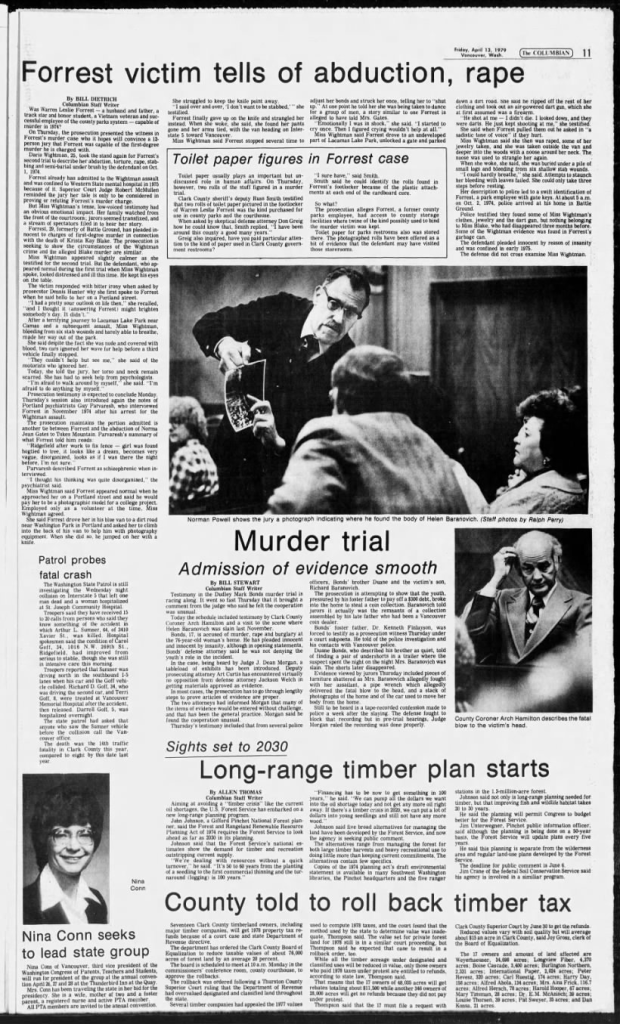

On October 1, 1974, WLF met a twenty-year-old woman** in Portland and lured her into his vehicle under the pretense of a photo shoot; but, instead of taking her pictures, he drove her to a deserted city park and raped her several times, torturing her and shooting her with darts from an air-powered dart gun. He then drove her to Camas, where he stabbed her six times with a knife near Lacamas Lake and attempted to strangle her, but she miraculously survived. He was arrested the following day on charges of kidnapping, rape and attempted murder.

After the brutal attack the young woman fell unconscious, and as Forrest believed she was deceased he removed all her clothes off then discarded her body in some nearby bushes; she woke up two hours later and managed to make it to a nearby city, where she was eventually discovered by people driving by and was taken to a nearby hospital. Luckily, she survived and once she was stable was able to give detectives a description of her assailant along with the distinctive details of the vehicle he drove (which was a blue 1973 Ford van). Her attacker did not help himself as he had made a point of saying hello to several of his colleagues as he was making his way through the park. As the incident took place under the Parks Department’s jurisdiction, investigators assumed that their guy was an employee and started looking into their employees along with their alibis.

A look at employee records showed that Forrest had taken off from work on the day of the attack, and he owned a 1973 blue Ford van that matched the perpetrator’s description very well; detectives quickly got a search warrant for his home and vehicle, and while searching his residence, they found jewelry and clothing that belonged to the victim. When the young woman was shown a picture of the young park’s employee, she was able to make a positively ID, and because Forrest was unable to provide a convincing alibi he was charged later the same day.

Shortly after Forrest’s arrest was made public, LE was also to identify him as the kidnapper of 15-year-old Norma Jean Countryman Lewis, who came forward and said that she had also been assaulted by him. According to her testimony, on July 17, 1974 she had been attempting to hitchhike out of Ridgefield and got picked up by him, and he then raped and beat her, and when they reached the slopes of Tukes Mountain, he bound and gagged her then tied her to a tree. Her assailant most likely had intentions of leaving her there to die, but she managed to chew through the restraints and hid in some nearby bushes until the following morning, when she emerged and found help; despite her powerful testimony, Forrest was solely charged with the kidnapping and attempted murder of his initial twenty-year-old accuser. Shortly after he was accused, his team of lawyers filed a motion for a psychiatric evaluation, which determined him to be legally insane, thus he was acquitted by reason of insanity and spent three and a half years undergoing treatment at the Western State Hospital in Lakewood, WA.

On July 16, 1976 two foragers were out picking mushrooms and wildflowers on some Clark County Parks Department property in Tukes Mountain near Battle Ground when they noticed a small brown shoe sticking out of some bushes. When they pulled on it, they realized it was attached to a human foot and immediately notified LE, who discovered the half-skeletonized body of a young woman that had been left in a shallow grave. Forensic examination of the mandible led the ME to determine that the remains belonged to twenty-year-old Krista Kay Blake, a hitchhiker who vanished without a trace from Vancouver on July 11, 1974.

Eyewitnesses that had been with Blake the day she was last seen alive recalled that she had gotten into a blue Ford van that was being driven by a young white male that they did not recognize; as WLF had the same vehicle, he immediately became a suspect. A closer look at the clothes she had been found wearing led to the discovery of small holes in her T-shirt, which forensic experts felt had been made by a dart gun similar to the one Forrest used on the kidnapped twenty-year-old woman. Because the victims’ clothes and skeleton showed no signs of stab wounds or bullet holes, the ME concluded that she had most likely been strangled to death.

Warren Leslie Forrest was charged on this basis with Blake’s murder in 1978, and although he had been detained at a mental institution, his attorney Don Greig filed a petition for another psychiatric evaluation, claiming his mental state had improved greatly and he even wanted to represent himself at trial (which was a request that had been granted). In the beginning four judges that had participated in Forrest’s earlier trials were removed due to concerns about possible bias, however this decision was later overturned, and Justice Robert McMullen was ultimately chosen to preside over the trial.

Forrest’s trial for the murder of Krista Blake began in early 1979, but a mistrial was declared after his attorney erroneously allowed a second dart gun unrelated to the case to be submitted as evidence. After that incident, his defense team filed a motion for a change of venue from Clark County to Cowlitz County, arguing that the media attention surrounding the murders would prejudice the jurors against their client; the motion was granted, and the trial resumed in April 1979 in Cowlitz County. During the proceedings Forrest pled not guilty, claiming he had been on vacation in Long Beach with his family at the time of the murder; this alibi had been backed up by his mother, who said in open court (while under oath) that her son had been at her residence with her at the time investigators supposed Blake had gotten into the blue van. However, prosecutors said her testimony was unreliable, pointing out that she had originally told investigators that her son had left her residence in the early evening and didn’t come back until the following morning. In addition to his mother, Sharon Forrest also testified on her husband’s behalf, although she told the court their relationship had been rocky and her husband had at times suffered from blackouts; she also insisted that he had been with her the entire time Blake was being killed and that he never showed any signs of being violent towards women.

Multiple witnesses testified against Forrest, claiming he was an acquaintance of Blake’s and that he had been seen with her at a variety of different times before her murder; one day one of his surviving victims took the stand and identified him as their assailant. Some of their claims were questioned by his defense team, as two of them had given descriptions of the suspected killer’s van that did not exactly match the one that he owned. WLF pled guilty to the kidnapping and attempted murder of the 20-year-old woman, claiming he had been suffering from PTSD at the time of the attack; however, he refused to admit any involvement in the murder of Krista Blake and the kidnapping of the 15-year-old.

After his conviction, Forrest was transferred to the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla and filed his first appeal in early 1982 (which was denied later that October); since then, he has filed numerous parole applications over the years, all of which have been denied due to the fact he is a suspect in other heinous and violent crimes against women.

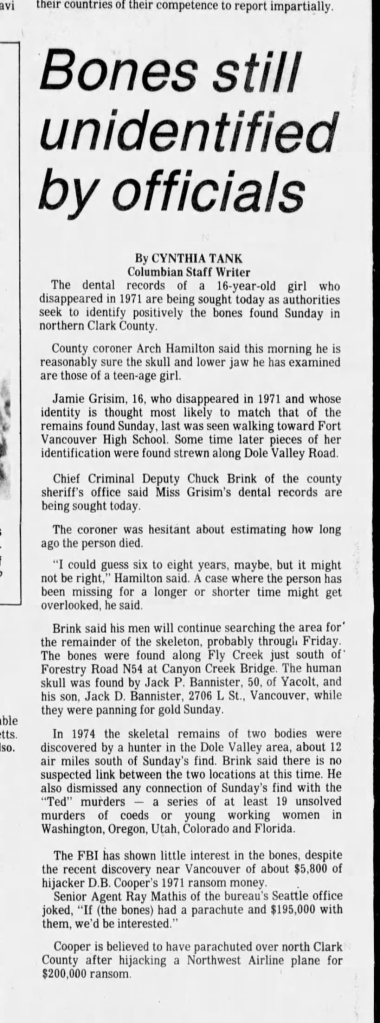

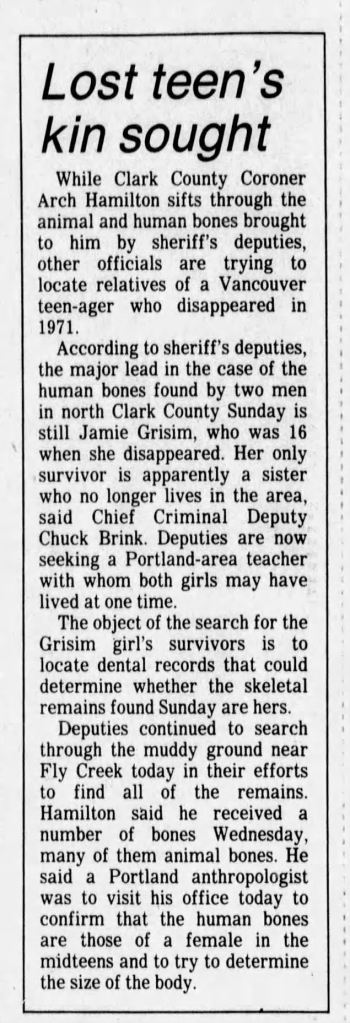

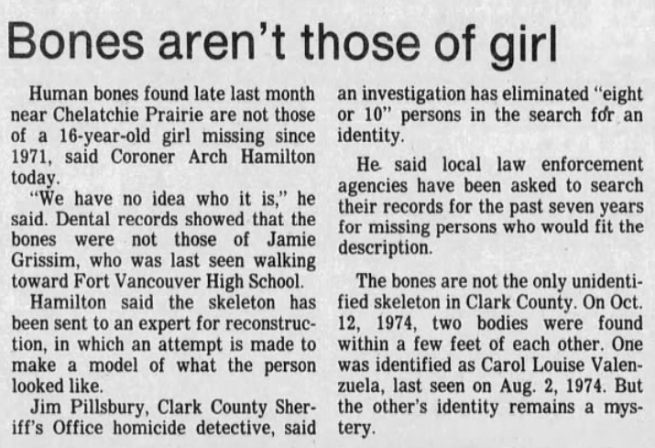

Unidentified Remains: In more recent years, Starr learned about some remains that were unidentified but had been found close to where her sister’s personal belongings were recovered; police said that dental records indicated that they did not belong to Jamie, however she continued to ask that they be tested for DNA so they could officially be identified. She was later told by an officer that the remains had been lost: ‘I just felt like (the detective) kicked me in the stomach because for over 30 years I held out hope she could be my sister.’

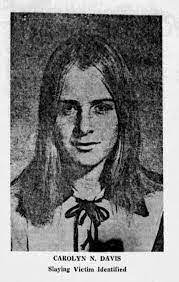

Reporter Dan Tilkin of KOIN-6 News in Oregon tracked down the last lab the unidentified remains were sent to, then passed the information along to Starr, who in turn contacted the ME that examined the original remains, Dr. Snow, who despite being eighty-three years old (at the time) still remembered the case. He later FedEx’ed her a copy of the correspondence related to the original remains, which she gave to the current medical examiner, who said they needed additional time to search for them; a few months later it was announced they had been found mixed in with another victim’s evidence. The remains went unidentified until July 2015 when Martha Morrison’s brother submitted a DNA sample to Eugene Law Enforcement and a positive ID was finally made.

Shortly after Forrest’s arrest was made public, LE was also to identify him as the kidnapper of 15-year-old Norma Jean Countryman Lewis, who came forward and said that she had also been assaulted by him. According to her testimony, on July 17, 1974 she had been attempting to hitchhike out of Ridgefield and got picked up by him, and he then raped and beat her, and when they reached the slopes of Tukes Mountain, he bound and gagged her then tied her to a tree. Her assailant most likely had intentions of leaving her there to die, but she managed to chew through the restraints and hid in some nearby bushes until the following morning, when she emerged and found help; despite her powerful testimony, Forrest was solely charged with the kidnapping and attempted murder of the initial twenty-year-old accuser. Shortly after he was accused, his team of lawyers filed a motion for a psychiatric evaluation, which determined him to be legally insane and as a result he was acquitted by reason of insanity and spent three and a half years undergoing treatment at the Western State Hospital in Lakewood, WA.

Martha Morrison: In December 2019, WLF was charged with the murder of seventeen-year-old Martha Morrison, who went missing from Portland, Oregon in September 1974; her skeletal remains were found in a densely wooded area on October 12, 1974 in Clark County roughly eight miles from Tukes Mountain, which was where Krista Blake’s remains were recovered. In 2014, investigators began reexamining physical evidence from Forrest’s criminal cases to see if it could be tested against unsolved crimes, and forensic technicians from the Washington State Police Crime Lab were able to isolate a partial DNA profile from bloodstains that had been found on his dart gun and checked it against Martha Morrison’s DNA, which eventually resulted in the positive identification of her remains.

Because Morrison’s murder took place in 1974 (before the Sentencing Reform Act was established in October 1984) there was no standard sentencing range, and a conviction of first-degree murder carried a life sentence. In January 2020, Forrest was extradited back to Clark County to await charges in Morrison’s murder, and on February 7, 2020 he pleaded not guilty. His trial was scheduled to begin on April 6, 2020 but it was delayed several times thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic; it resumed in early 2023, and on February 1, 2023 a jury found him guilty of Morrison’s murder and sixteen days later, he received another life sentence.

During his sisters trial, Michael Morrison (through a Zoom call) begged Forrest to grant the same closure that he’s found to the other families of his victims: ‘you cannot undo the past, but you have the power to let those families find some peace,’ and urged Forrest to ‘put to end the wondering.’ But when he was asked by the judge if he wanted to address the court, he simply replied, ‘no, your honor,’ eliciting reactions of disgust from those in the gallery.

About Forrest, Senior Deputy Prosecutor Aaron Bartlett said he ‘has claimed to feel remorse and guilt for the crimes he committed and for his victims. Forrest, who will now assuredly never step foot outside of prison, has the opportunity to put his words into action and end the wondering for those families. Until he does, the state will continue to seek to hold him accountable for his crimes.’

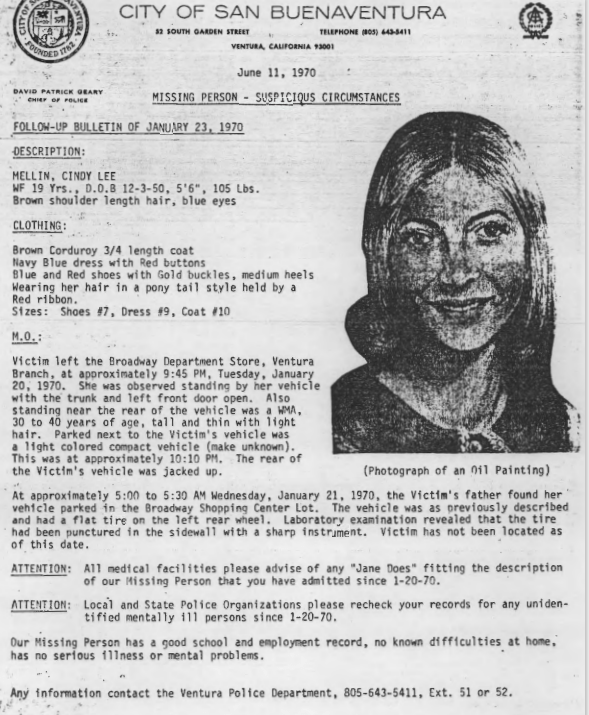

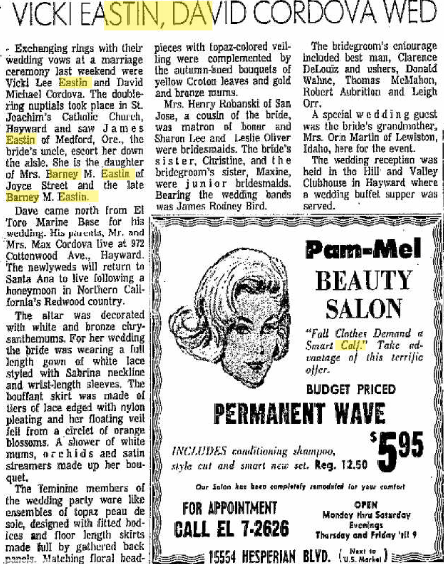

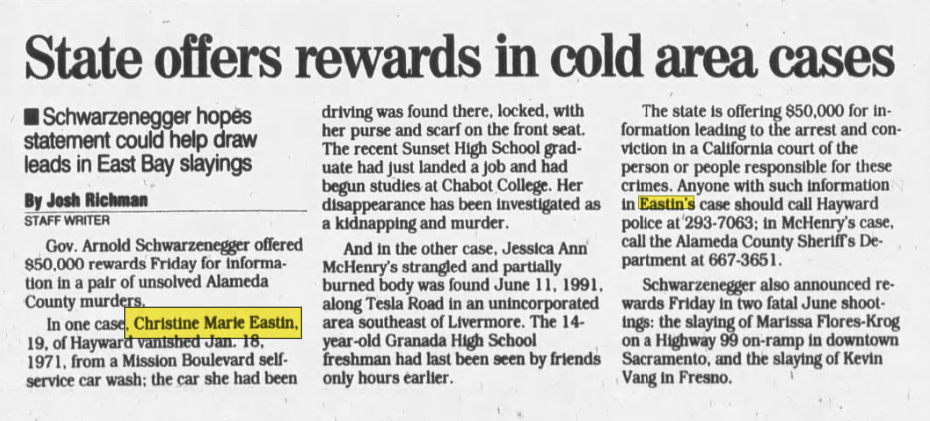

Additional Victims: Aside from Krista Blake and Martha Morrison, Warren Forrest remains the main suspect in the disappearances and murders of at least six more teenagers and young women across Oregon and Washington: eighteen-year-old Barbara Ann Derry disappeared on February 11, 1972 and was last seen hitchhiking on a highway in Vancouver trying to get to Goldendale (where she had recently moved for college); her remains were found on March 29, 1972 at the bottom of a silo inside the Cedar Creek Grist Mill and it was determined that she died from a stab wound to her chest. Fourteen-year-old ninth grader Diane Gilchrist went missing on May 29, 1974, and her parents claimed their daughter had left through her second-story bedroom window in their home in downtown Vancouver; her remains have never been recovered.

Nineteen-year-old Gloria Nadine Knutson was last seen by several acquaintances at a Vancouver nightclub called ‘The Red Caboose’ on May 31, 1974. One witness told investigators that the Hudson Bay High School senior had sought out his help in the early morning hours, saying that somebody had tried to rape her and was now stalking her; he also reported that she had asked him to drive her home, but his car had been out of gas. Distraught and out of options, Knutson was forced to walk to her residence, and disappeared immediately after; her skeletal remains were found by a fisherman in a forested area near Lacamas Lake on May 9, 1978.

Twenty-year-old married, mother to infant twins Carol Platt-Valenzuela disappeared on August 4, 1974 while hitchhiking from Camas to Vancouver; her skeletal remains were discovered a little over two months later on October 12, 1974 by a hunter in the Dole Valley (just outside of Vancouver). Because of how close they were to the bones of Morrison, authorities believe that Forrest most likely killed both women.

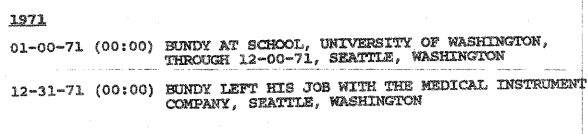

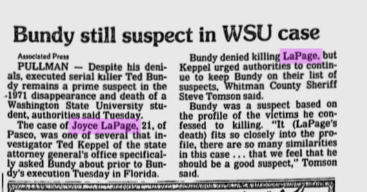

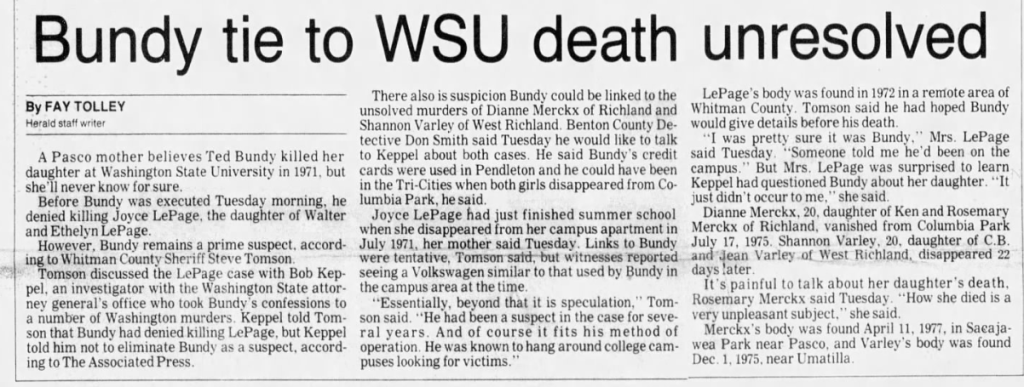

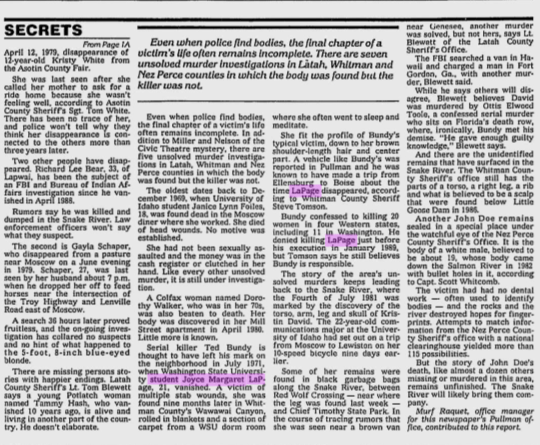

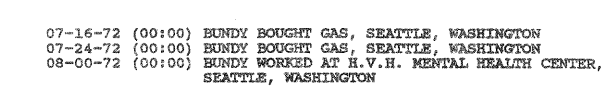

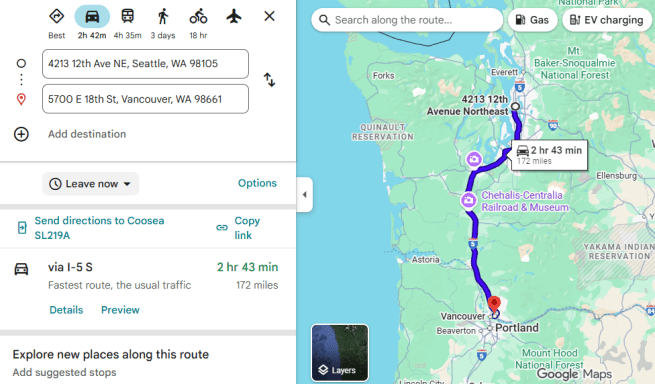

Ted Bundy: At the time Jamie disappeared in late 1971 Ted Bundy was living in Seattle at the Rogers Rooming house on 12th Avenue NE and was in the middle of his long-term relationship with Elizabeth Kloepfer. He was also an undergraduate psychology student at the University of Washington and was employed as a delivery driver for Pedline Supply Company, which was a family-owned medical supply company (he was there from June 5, 1970 to December 31, 1971). Even though I don’t think he was responsible for the disappearance of Jamie Grisim, and its unknown if he was ever questioned about her disappearance. In addition to Bundy the serial killer Gary Gene Grant was also active in the Pacific Northwest in 1971, however had already been arrested by the time Jamie disappeared in December.

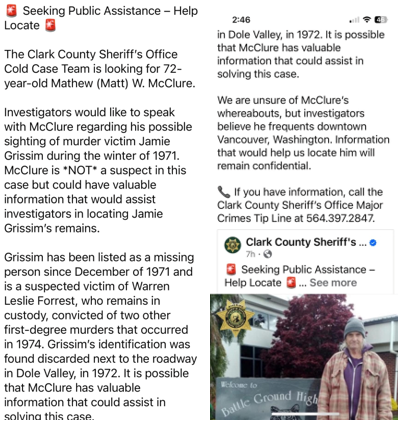

Updates: In early December 2025, investigators reported progress in Jamie Grisim’s case after successfully locating what they thought was a long-lost witness. According to Clark County cold case investigator Doug Maas: ‘we tracked down a witness that we’ve been looking for a long time. He is now in his early 70’s, but he clearly recalled back in the winter of 1971. He had a spot with his family, ran away, stumbled into the woods and fell and came face-to-face with the remains of a young woman.’ Maas went on to elaborate that the area he identified was less than two miles away from where Jamie’s school ID was found (which was less than one mile from where the remains of Carol Valenzuela and Martha Morrison were recovered).

Shirley A. Pries died at the age of eighty-four on July 15, 2007 in Hillsboro, OR. According to her obituary, she was a homemaker and lived the majority of her life in Onalaska, WA; her husband Hans died in 2001. James Richard Grisim died on July 25, 1990 in Riverside, California at the age of seventy-two.

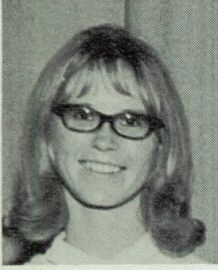

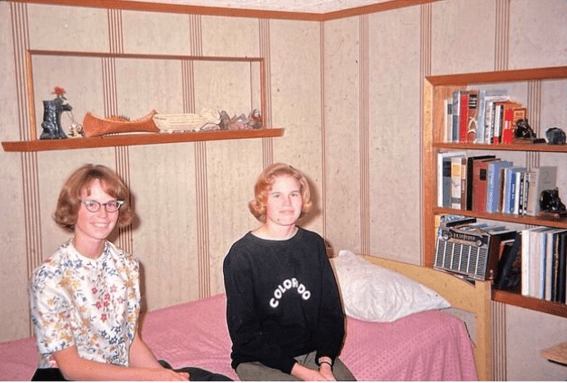

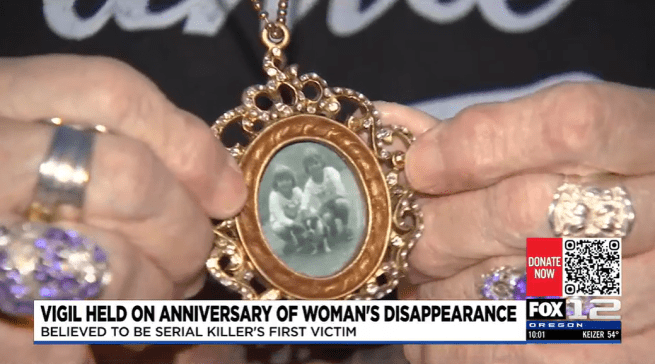

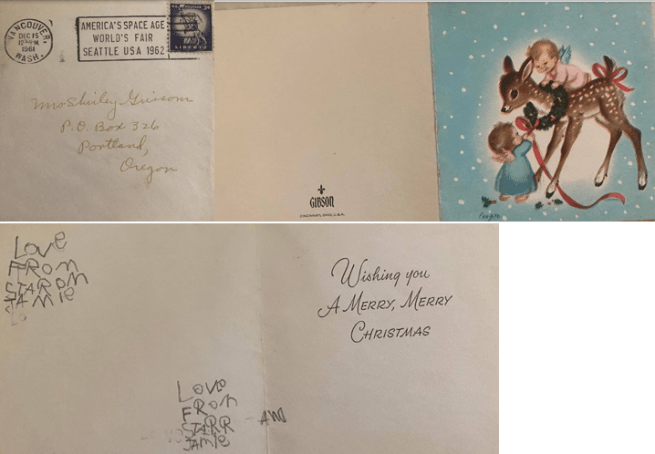

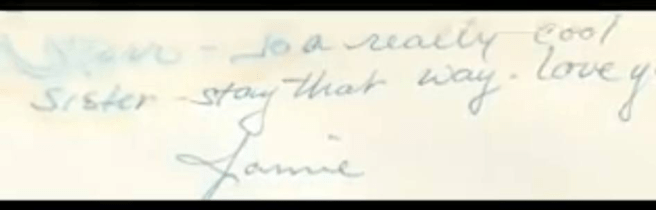

After Starr Grisim-Lara graduated from Hudsons Bay High School in 1974 she went on to attend Portland State University as well as Portland Community College; she currently lives in Vancouver, WA with her husband, children, and grandchildren. After Jamie disappeared Starr struggled for many years: she began to rebel as a teenager by running away from home and she had a son in high school. She is now happily retired and spends her time running multiple websites devoted to helping get Jamie’s name out there and is a passionate advocate for the victims of Warren Leslie Forrest. Sadly she doesn’t have many tangible memento’s related to her sister: a half-dozen photographs, a sheaf of school records, a small Christmas card (signed in childlike block letters), and a sketch of a woman’s face. It’s not much to the average person, but to her these items are more precious than gold: it’s proof that Jamie existed. About her, Starr said: ‘we were thought of as twins. Irish twins, they called it.’

About Forrest, Starr said: ‘I do forgive him for killing Jamie. I do. But I won’t forgive him for withholding the truth. You can’t kill my sister and expect I’m just going to forget about it. And that’s what keeps me going.’ … ‘The fact he could kill so many girls, and nobody even knew about him? He deserves a bad reputation. People need to know how evil he is.’

Starr hopes that one day Forrest will tell the truth about her what happened to Jamie but knows it’s unlikely he’ll ever talk, as he denied through a prison spokesman that he had anything to do with her sisters disappearance: ‘I want to know where my sister’s bones are. I would like to know how she died, if he even remembers her. I was actually relieved to know he was still alive, because he has that knowledge.’

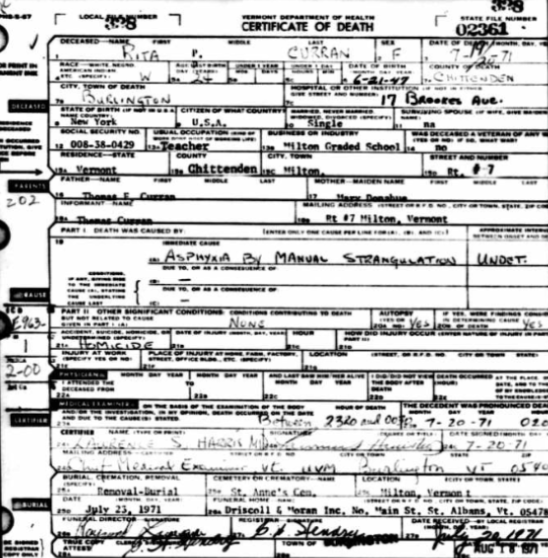

In an audio recording from one of his parole hearings, Forrest recalled details of the horrific crimes he committed, and reiterated that he was ‘a different person’ now than he was forty years prior, saying: ‘I abducted a 19-year-old female stranger under the ruse of giving her a ride…forcing the victim to undress and during a struggle I choked the victim to death.’ The Washington State Parole Board has denied his application for release on multiple occasions, and as of December 2025 he remains in prison. Though he remains a leading suspect, Warren Leslie Forrest has never been charged with Jamie’s murder; her death certificate was issued March 23, 2009 with her presumed death date listed as December 7, 1971. As of December 2025, Jamie Rochelle Grisim remains missing.

* I have incorrectly seen Jamie’s last name spelled as ‘Grisom,’ ‘Grissim,’ and ‘Grisim.’

Works Cited:

Delgado, Amanda. (January 10, 2022). Taken December 26, 2025. fromhttps://projectcoldcase.org/2022/01/10/jamie-grissim/

Lopez, Julia. ‘Vancouver Family Honors Missing Teen as Investigators Link Case to 1970s Serial Killer.’ (December 8, 2025). Taken December 17, 2025 from http://www.kptv.com

Prokop, Jessica. (February 17, 2023). ‘Clark County Serial Killer Warren Forrest Sentenced to Life in Prison in 1974 Murder.’

Prokop, Jessica. ‘Missing Teen’s Sister Hopes for Conviction in Warren Forrest Trial.’ (December 5, 2025). Taken December 17, 2025 from http://www.columbian.com

A list of divorces granted in the state of Oregon published in The Oregon Daily Journal on October 26, 1957.