Preface: I don’t normally have to do this, as I don’t normally write about people that are still with us, but every member of Warren Leslie Forrest’s nuclear family is not only still alive, but (most of them) go by their original surname. Because of that, I do feel the need to say that finding the information I did was a quick Facebook/Google search away, and it took me all of about three minutes to find most of it. I didn’t hire anyone to track them down or figure out their identities: it was all right there.

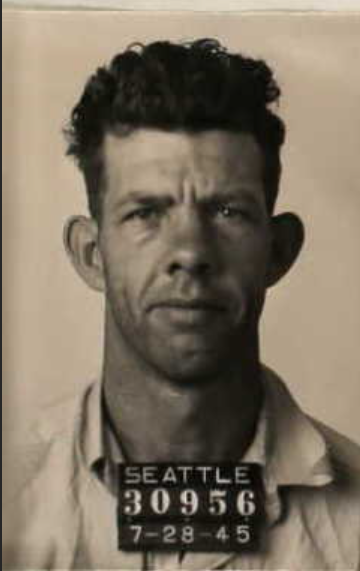

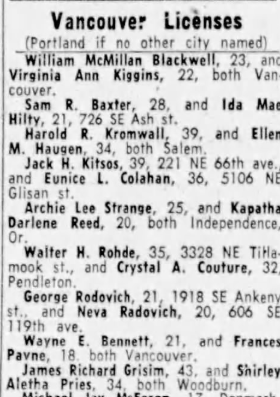

Introduction: Warren Leslie Forrest was born on June 29, 1949 to Harold and Dolores Forrest in Vancouver, WA. Harold Fred Forrest was born on November 24, 1917 in Moscow, Idaho and Delores Beatrice Harju was born on June 20, 1925 in Eveleth, Minnesota. At the age of twenty-seven on September 16, 1940, Harold was inducted into active military service with the US Army in pursuant to the Presidential order of August 31, 1940 (also known as the Burke-Wadsworth Act), which required all men between twenty-one and thirty-six years of age to register with their local draft boards (when the US entered World War II, all men from eighteen to forty-five were subject to military service, and all males from eighteen to sixty-five were required to register with their local draft boards). Mr. Forrest and Dolores were wed on July 3, 1944 in Vancouver, and he was honorably discharged from the military on January 27, 1945. The couple had three children together: James (b. 1946), Marvin (b. 1948), and their youngest, Warren.

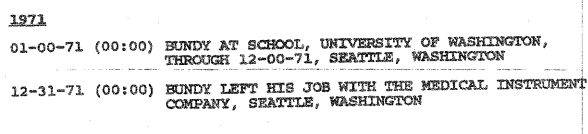

Background: As a child, Warren Forrest was a dedicated boy scout and worked his way all the way up to Eagle Scout. When he attended Fort Vancouver High School in the mid-1960’s he excelled at academics and was an exceptional athlete: he played baseball, ran cross-country and earned his role as the captain of the track and field team. In October 1967 he got drafted into the US Army during the Vietnam War (along with his brother, Marvin), and served as a missile crew service gunner and fire control crewman for the 15th Field Artillery Regiment in Homestead, Florida, reaching the rank of Specialist 5; when he relocated to Fort Bliss, TX he served in the 7th Battalion of the 60th Airborne Artillery, where he was a ‘senior gunner.’

It appears for the most part that the Forrest brothers had completely normal childhoods, aside for one glaring thing: two of the three boys hit people with their cars when they were teenagers. On January 16, 1966 a six-year-old child ran around a city bus directly into the path of Marvin Forrest; they were taken to Vancouver Memorial Hospital and thankfully only suffered some minor bruising and lacerations. Later that same year on May 26th Rebecca Peterson was driving a car along with her friend Marilyn Sutcliffe when they were hit by a vehicle driven by a then sixteen-year-old Warren L. Forrest. The impact of the collision caused Peterson to lose control of her vehicle, which subsequently jumped the curb and struck two young female pedestrians. The accident resulted in both vehicles being deemed ‘total economic losses,’ and afterwards Forrest was brought up on charges in juvenile court for passing a stop sign, failure to yield the right of way, and for having defective breaks. In September of the following year, he was taken to court by one of the two girls he hit, named Robin DeVilliers, who had suffered injuries to both of her legs, heels, thighs and back as a result of the accident. I was unable to find the resolution of the court case, but I’m assuming it wasn’t dragged out as he left for the Army the following month.

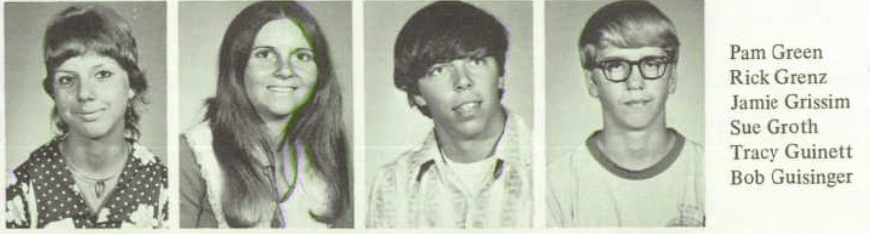

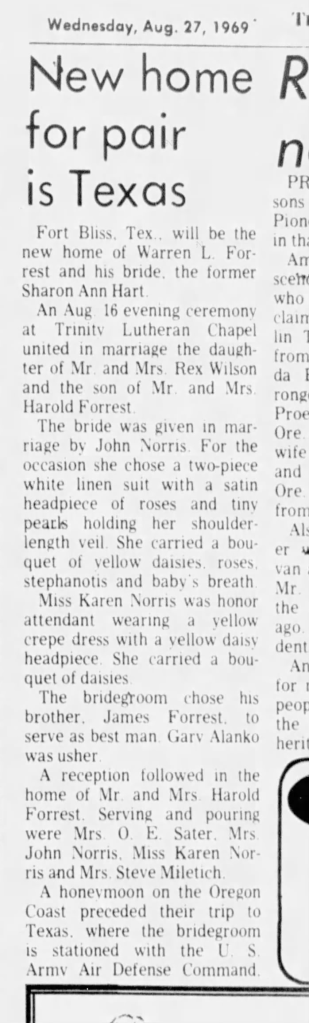

Upon his return from the Army, Forrest returned to Vancouver and married his high school sweetheart, Sharon Ann Hart on August 16, 1969, and the couple had two children together: Leslie (b. 1971) and Lane (b. 1974). Sharon was born on January 27, 1949 in Omaha, Nebraska, however as her daughter Leslie pointed out in a Facebook post, in every newspaper article about her and Warren’s engagement/marriage, her last name is Hart, but according to her high school yearbook, her full maiden name was ‘Sharon Ann Wilson.’ According to the 1967 Ft. Vancouver High School yearbook (she graduated in the same class as Warren), she performed in the yearly Christmas play and was a member of the marching band, Big Sister/Little Sister, the Future Homemakers of America Club, Pep Band, and the Health Careers Club.

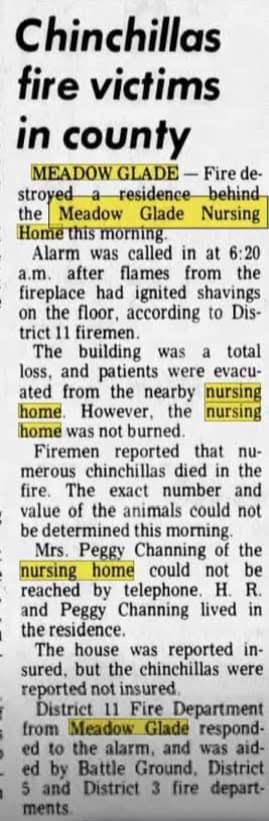

Shortly after their wedding, the newlyweds moved to Fort Bliss, Texas, then again to Newport Beach, California, where Warren enrolled at the North American School of Conservation and Ecology; he quickly lost interest in academics and dropped out at the end of his first semester. In late 1970, Warren and Sharon moved for a third time to Battle Ground, WA, where he found employment with the Clark County Parks Department as a general maintenance worker. For a while, everything seemed picture perfect for the seemingly happy young couple… until suddenly it wasn’t.

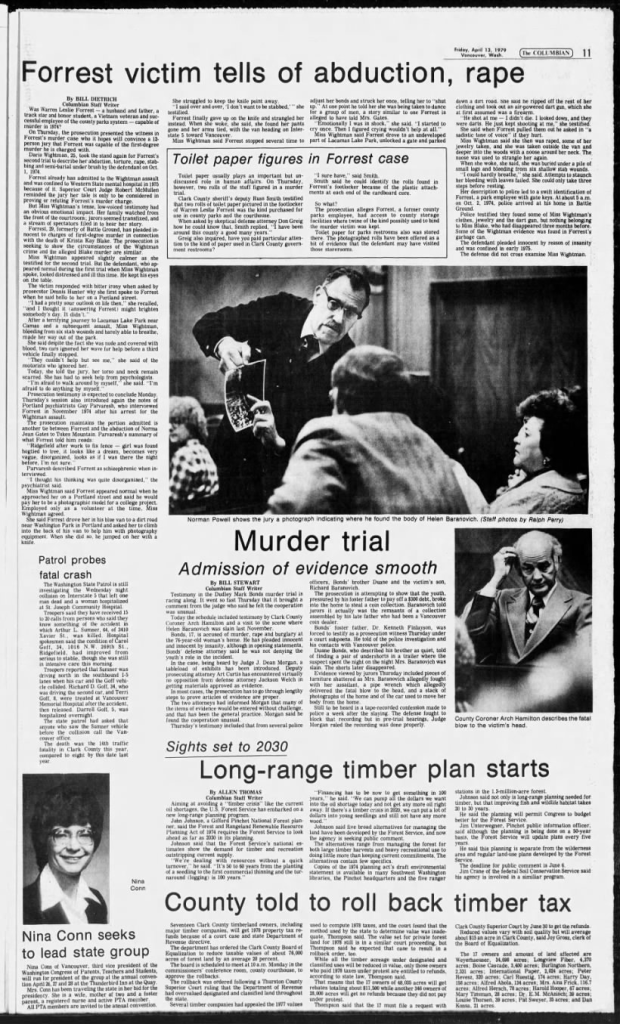

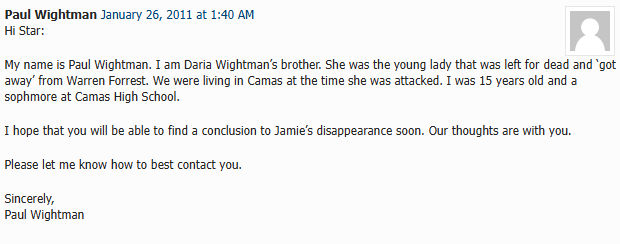

On October 1, 1974 Warren Forrest kidnapped twenty-year-old Daria Wightman after he saw her standing on a street corner in downtown Portland and pulled over to talk to her: he shared with her that he was employed at Seattle University and had been working on a thesis project for class and offered her money to pose for pictures for him. She accepted his offer and climbed into his van and went with him to the Washington Park area of Portland, and it was at that point that he pulled out a knife and threatened her, then bound her with tape. He then drove roughly 25 miles to Lacamas Park, a heavily wooded and sparsely populated area of Clark County, where he sexually assaulted her; when he was finished, he shot her in the chest with a hand honed dart (which refers to the process of sharpening or refining an edge manually using either a whetstone or steel) from a .177 caliber dart pistol then led her 100 feet down a path by a rope around her neck.

Once they reached his intended destination, he sat the young woman on a log and choked her to the point of unconscientious. From there, he stabbed her five times in the chest then laid her naked body next to a log and covered it with brush and leaves (at some point during the encounter her attacker had removed all of her clothes and taken them with him)… But by some miracle, the victim was not dead, and after struggling for about two hours she finally made her way to a roadway, where she was able to get the attention of a passing motorist, who took her to a nearby hospital. Once she was stabilized, the woman was able to give detectives a description of her assailant along with the details of the very distinctive vehicle that he drove (a blue 1973 Ford van). She also told them that as he was driving through the park he slowed down on several occasions and greeted several people, and investigators quickly deduced that their guy was an employee of the department.

A look at employee records showed that Forrest owned a 1973 blue Ford van that closely matched the one the perpetrator drove, and that he had taken off from work on the day of the attack to ‘go to a doctor’s appointment in Portland.’ Detectives quickly got a search warrant for his home and vehicle, and while searching his residence found jewelry and clothing that belonged to the victim. In a footlocker discovered in Forrest’s van, detectives found a gun, tape, and baling twine that was similar to what was used on other victims. When the young woman was shown a picture of the young Park’s Department employee, she was able to make a positive ID; Wrightman was also able to identify the suspect in a lineup, and because WLF was unable to provide a convincing alibi for where he was on the day she was attached, he was charged later the same day.

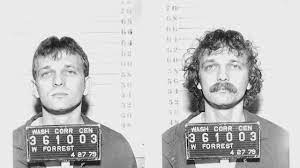

On October 2, 1974, Forrest was arrested on charges of kidnapping, rape and attempted murder and was held in lieu of $60,000 bond. At the time of his arrest, he was twenty-five-years old and weighed 155 pounds; he stood at 5’9” tall, wore his light brown hair at his shoulders, and had what was described as a ‘bushy mustache.’ On October 5, 1974 he was arraigned on charges of rape, assault with the intent to kill, and armed robbery (after he assaulted her, he also took her watch and bracelets), and he entered a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity.

Shortly after his arrest was made public, detectives were able to also able to link him to the kidnapping, rape, and assault of fifteen-year-old Norma Countryman, who had been attempting to hitchhike out of Ridgefield on July 17, 1974 when she got in Warren’s van after he pulled over and offered her a lift. From there, he raped then beat her, and when they reached the slopes of Tukes Mountain, he gagged her with her own bra then hogtied her to a tree and told her he would ‘return’ to her later… but, the petite young lady had a fierce will to live and chewed her way through her restraints and hide in some nearby bushes until the sun rose and she was able to flag down a Parks employee for some help. The suspect returned to the scene of the crime the following night and picked up what he had used to bind her to the tree as well as the bra he used to gag her. Despite Countryman’s powerful testimony in court, Forrest was solely charged with the kidnapping and attempted murder of the Daria Wightman.

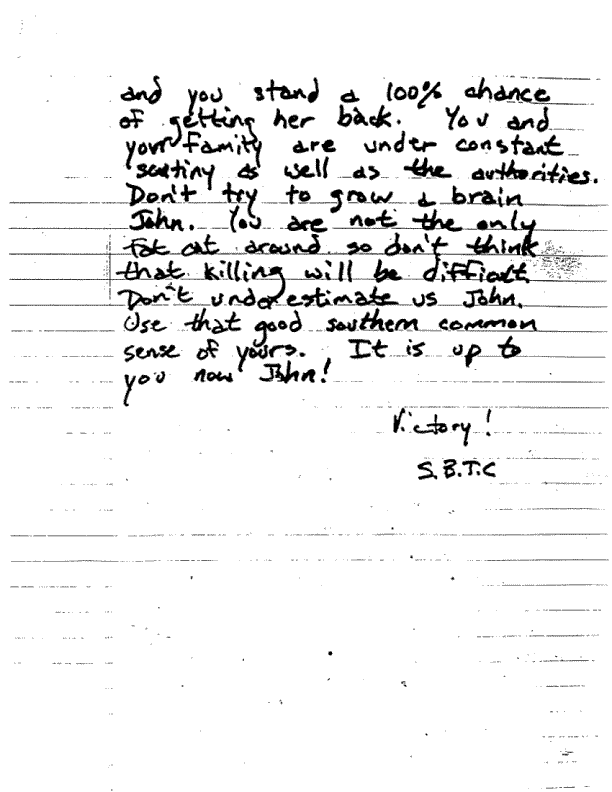

Warren Forrest pled not guilty due to reason of insanity. His legal team filed a motion for him to undergo a psychiatric evaluation, and thanks to examinations by three local psychiatrists, it was determined he was legally insane, and on January 31, 1975 he was committed to the Western State Mental Hospital in Steilacoom, WA. It’s important to note that, according to an article published in ‘The Columbian’ on January 30, 1979, evidence that may have been ‘crucial’ to the prosecution of Forrest for a separate murder was lost in early 1975 when Sharon was allowed to go through a box of evidence after the Clark County prosecutor and sheriff’s department deemed the entire case to be ‘disposed of.’ Amongst the items that were taken were keys, twine, a knife, adhesive tape, a victims clothing, and ‘vacuum sweepings’ that were taken from Forrest’s 1973 Ford van shortly after his arrest. About the incident, Detective Frank Kanekoa of the Clark County Sheriff’s Department said that ‘Sharon Forrest was allowed to rummage through a box of evidence and take what she wanted sometime in early 1975 because Warren had already pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity.’ That same evidence may have played a major role in Forrest’s later trial in January 1979 for the murder of Krista Kay Blake.

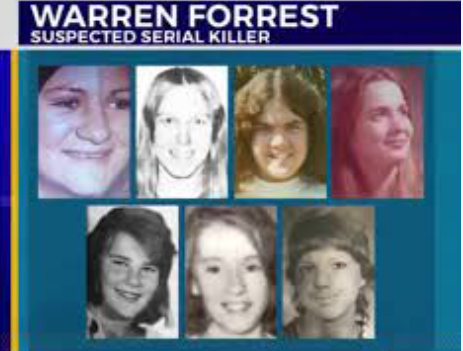

A year and a half went by. On July 16, 1976 two foragers were out picking mushrooms and wildflowers on some Clark County Parks Department property in Tukes Mountain near Battle Ground when they noticed a small brown shoe sticking out of some bushes. When they gently tugged on it, they realized it was attached to a human foot and immediately notified LE, who discovered the half-skeletonized body of a young woman that had been left in a shallow grave. Forensic examination of the victims mandible led the ME to determine that the remains belonged to Krista Kay Blake, a hitchhiker who vanished without a trace from the area of 29th and ‘K’ St. in Vancouver on July 11, 1974.

Krista’s remains were discovered in a shallow grave at ‘Tukes Mountain’ on Clark County Parks property; she had been partially unclothed and had been missing her bra, and her hands and feet were ‘hogtied’ behind her back with baling twine (which was uncovered around 100 feet from her gravesite). Nineteen-year-old Blake was known to hitchhike, and at the time she was killed was living on NE 119th Street in Vancouver. After she disappeared two eyewitnesses came forward and told detectives that they observed her and the suspect that had been driving the blue van together around the Lewisville Park area sometime prior to the day she disappeared; separate people came forward and reported they had seen the same van driving around Tukes Mountain on or around the date that Blake was last seen alive. It’s worth noting that Norma Countryman’s assault took place one week after the disappearance of Krista Kay Blake.

Because Warren Leslie Forrest had the same van as the suspect and worked at the park where the victim had been found, he immediately became a person of interest. Because of advanced age of the body a great deal of physical evidence had been lost, however a closer look at the clothing that the young woman had been wearing led to the discovery of incredibly small punctures in her T-shirt, that forensic experts determined were made by a dart gun similar to the one that Forrest used on Daria Wrightsman. Because the victims’ clothes and skeleton showed no signs of stab wounds or bullet holes, the ME concluded that she had most likely been strangled to death.

Not long into the investigation, detectives realized that on the day Blake had disappeared, Forrest wasn’t at work because ‘he had a doctors appointment,’ and on top of that he had no alibi: his mother said that he had spent part of the day at her house, but had ‘left early in the evening’ and did not return until the following morning. Warren Leslie Forrest was charged on this basis with Blake’s murder in October 1978, and despite already being detained inside of a mental institution, his attorney Don Greig filed a petition for a new psychiatric evaluation, claiming his mental state had improved greatly and he even wanted to represent himself at trial a request that had been granted). In the initial stages, the four judges that had participated in WLF’s earlier trials were removed from consideration due to concerns about possible bias, however this decision was later overturned, and Justice Robert McMullen was ultimately chosen to preside over the case.

Warren Forrest’s trial for the murder of Krista Blake began in early 1979, but a mistrial was declared after his attorney erroneously allowed a second dart gun unrelated to the case to be submitted into evidence. After that incident, his defense team filed a motion for a change of venue from Clark County to Cowlitz County, arguing that the media attention surrounding the murders would prejudice the jurors against their client; the motion was granted, and the trial resumed in April 1979 in Cowlitz County. In the beginning of the proceedings, Forrest pled not guilty and claimed he had been on vacation with his family in Long Beach at the time of the murder; this alibi had been backed up by his mother, who also said in open court (while under oath) that her son had been at her residence with her at the time investigators supposed Blake had gotten into the blue van. However, prosecutors said her testimony was unreliable, pointing out that she had originally told investigators that her son had left her residence in the early evening and didn’t come back until the following morning. In addition to Dolores, Sharon Forrest also testified on Warren’s behalf, although she told the court their relationship had been ‘rocky’ and her husband had at times ‘suffered from blackouts;’ she also insisted that he had been with her the entire time Blake was being abducted and killed, and that her husband never showed any signs of being violent towards women.

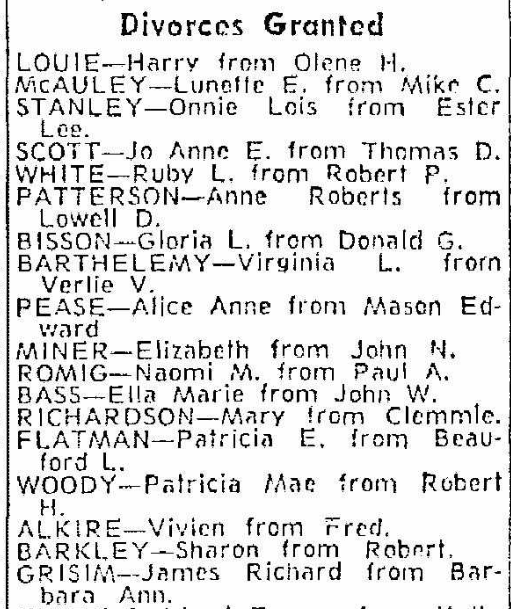

Multiple eyewitnesses testified against Forrest, and claimed he was a known acquaintance of Blake’s and that the two had been seen together at multiple times before her murder; however, some of their claims were scrutinized by his defense team, as two of them had given a description of the suspects van that did not perfectly match the one that he owned. One day during the trial, he admitted guilt to the kidnapping and attempted murder of Daria Wrightman, claiming he attacked her due to untreated PTSD from serving in the military. However, when confronted, he absolutely refused to admit guilt for the murder of Krista Ann Blake and the kidnapping and assault of Norma Countryman, and because of this the prosecutor’s office insisted that he was guilty of all charges (as each crime matched his MO). Warren Forrest was ultimately found guilty and was sentenced to life imprisonment with a chance of parole and was sent to Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla; he was convicted before mandatory sentencing laws and was eligible for parole for the first time in 2014. Sharon Forrest filed for divorce from Warren in June of 1980.

Forrest filed an appeal in early 1982, which was denied later that October. Since then, he has filed numerous parole applications over the years, confirmed ones in April 2011, April 2014, July 2017, and May 2022), all of which have been denied due to the fact he is a suspect in many other heinous and violent crimes against women. At one of his parole hearings, both of his surviving victims took the stand and identified him as their assailant.

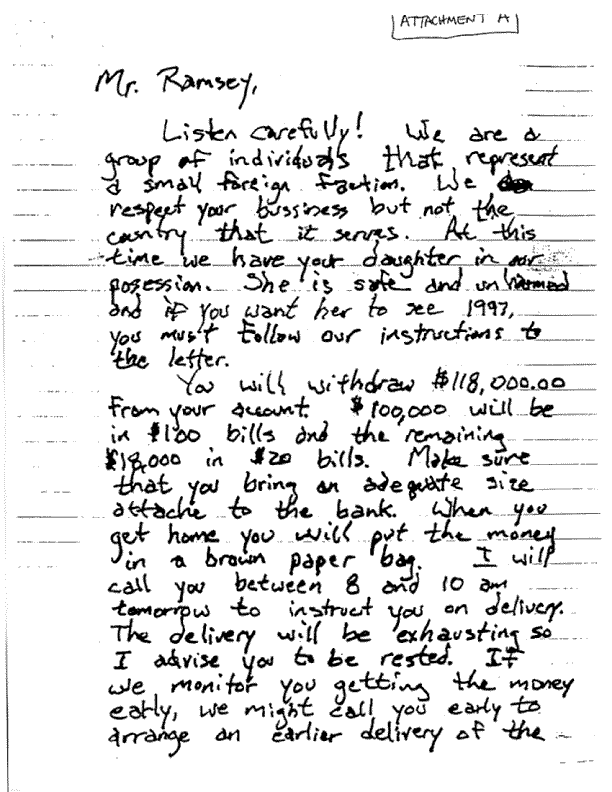

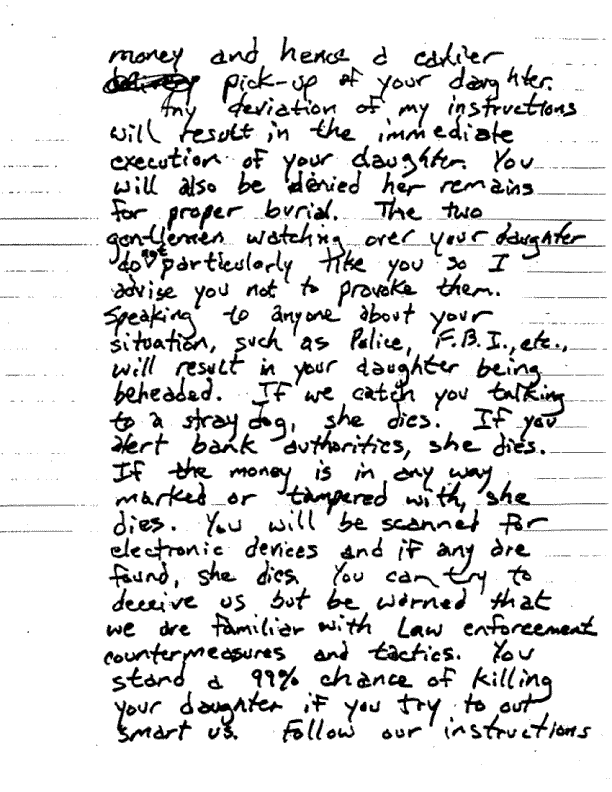

The Confession of Krista Blake/2017: Since his initial convictions, Warren Leslie Forrest has remained a suspect in multiple kidnappings, disappearances, and murders around Clark County that took place in the early to middle 1970’s, however he has refused to help LE with their investigations: at a parole hearing in 2017, Forrest finally confessed to killing Krista Blake, stating she had been severely depressed and stressed out at the time of her murder, and he ‘did not intend’ to kill her at first, but was forced to after she attempted to get away from him. During that same hearing he also casually confessed to sixteen additional crimes against women that took place between 1971 and 1974, ranging from voyeurism to murder, and said he was ‘remorseful for his actions.’ Despite his confessions, Forrest’s application for parole was denied and he was prohibited from filing another appeal until March 2022 as the board stated he ‘continued to pose a danger to society and made minimal progress in ameliorating his behavior.’ In an audio recording from one of his parole hearings, Forrest recalled details of the horrific crimes he committed, and reiterated that he was ‘a different person’ now than he was forty years prior, saying: ‘I abducted a 19-year-old female stranger under the ruse of giving her a ride…forcing the victim to undress and during a struggle I choked the victim to death.’

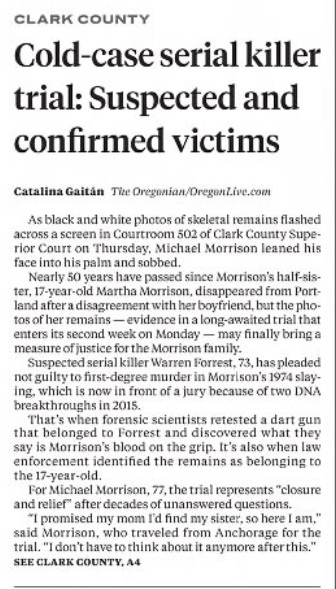

In June 2017 Clark County investigators met with Warren Forrest and told him they’re working to prove he killed five additional young women across Washington and Oregon: Jamie Rochelle Grisim (1971), Barbara Ann Derry (1972), Carol Louise Platt-Valenzuela (1974), Martha Morrison (1974), and Gloria Nadine Knutson (1974). When the parole board asked him about the other possible victims, he would only say that he felt ‘sorrow for those families,’ and that talk of other crimes is ‘not factually’ accurate. He also said that he only committed the crimes because he was stressed out from working two jobs, going to school, and being a husband and father, and: ‘the only option I had was to distract myself, and I chose to live out those violent fantasies.’

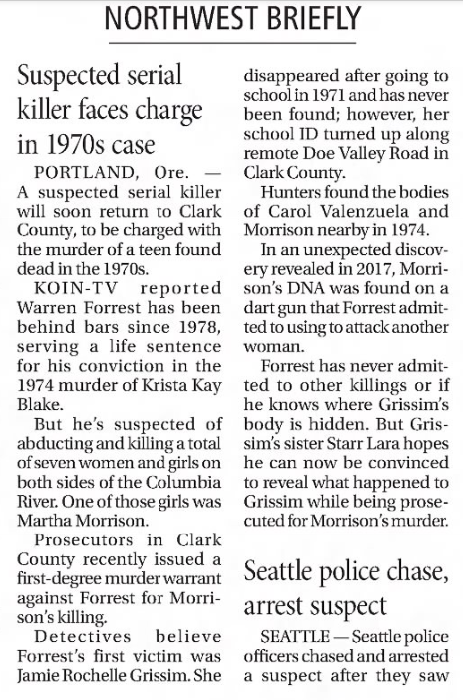

Martha Morrison: In December 2019, Warren Forrest was charged with the murder of seventeen-year-old Martha Morrison, who went missing from Portland, OR in September 1974. Her skeletal remains were discovered on October 12, 1974 in Clark County, only eight miles from Tukes Mountain (where Krista Blake’s body was recovered). Unfortunately, authorities at the time were unable to positively identify the remains and she was known simply as a ‘Jane Doe’ for many years; in 2010, Morrison’s half-brother submitted a DNA sample to police in Eugene, OR and in 2014 investigators began examining physical evidence from Forrest’s criminal cases to determine if anything from them could be used in unsolved crimes.

Forensic experts from the Washington State Police Crime Lab were able to isolate a partial DNA profile from some blood that had been found on Forrest’s dart gun, and cross-referenced it with Michael Morrison’s DNA, which lead to the positive identification of Morrison’s remains. In January 2020, WLF was extradited back to Clark County to await charges in Morrison’s murder, and on February 7, 2020 he pleaded not guilty. The trial was scheduled to begin later that year on April 6, 2020 but was delayed on several occasions thanks to the pandemic, however it resumed in early 2023 and on February 1, 2023 a jury of his peers found Warren Leslie Forrest guilty for the murder of Martha Morrison. Only sixteen days later, he received another life sentence. He remains the prime suspect in the disappearances and murders of at least five more teenagers and young women, and in each case, the perpetrator exhibited a similar modus operandi to Forrest:

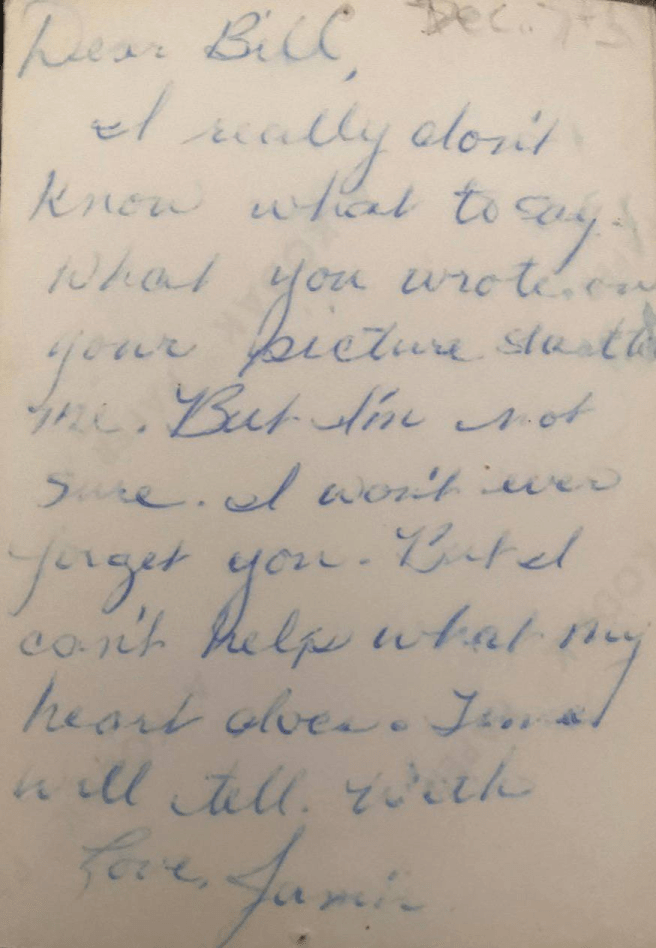

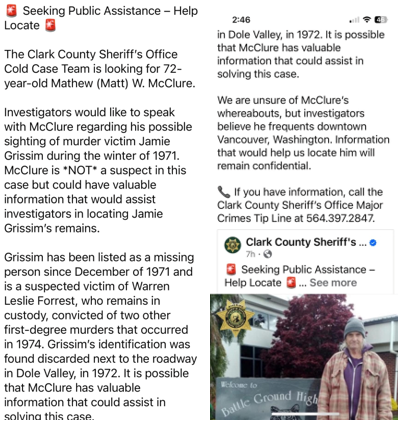

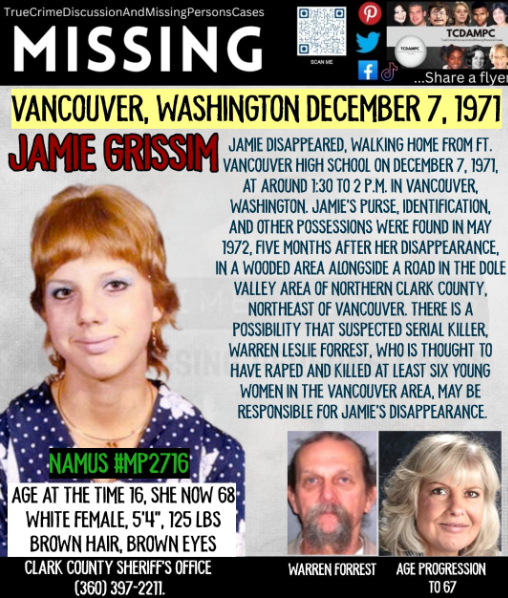

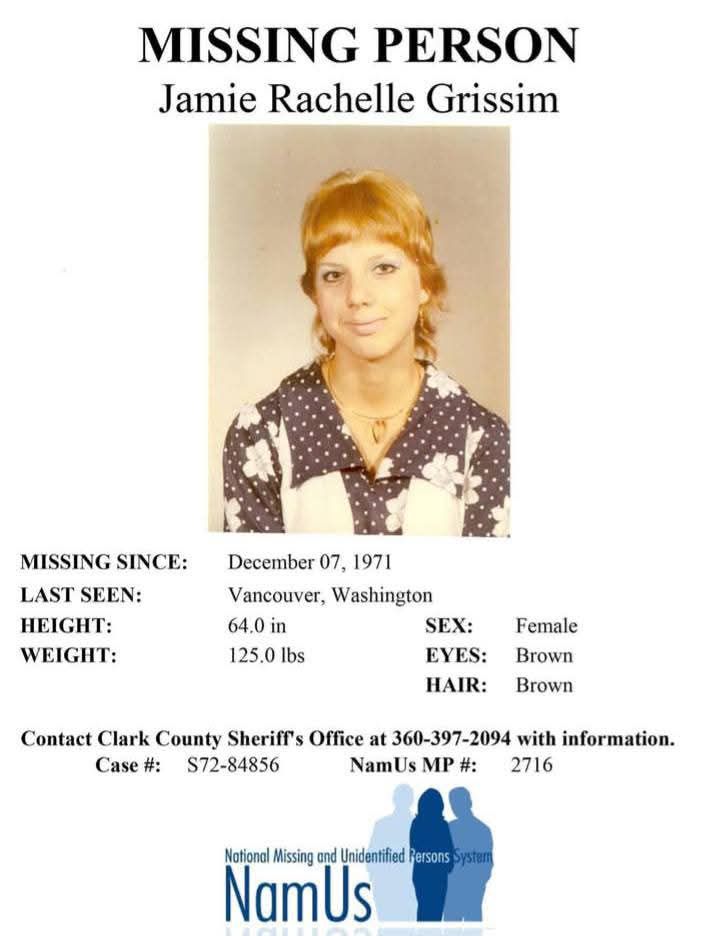

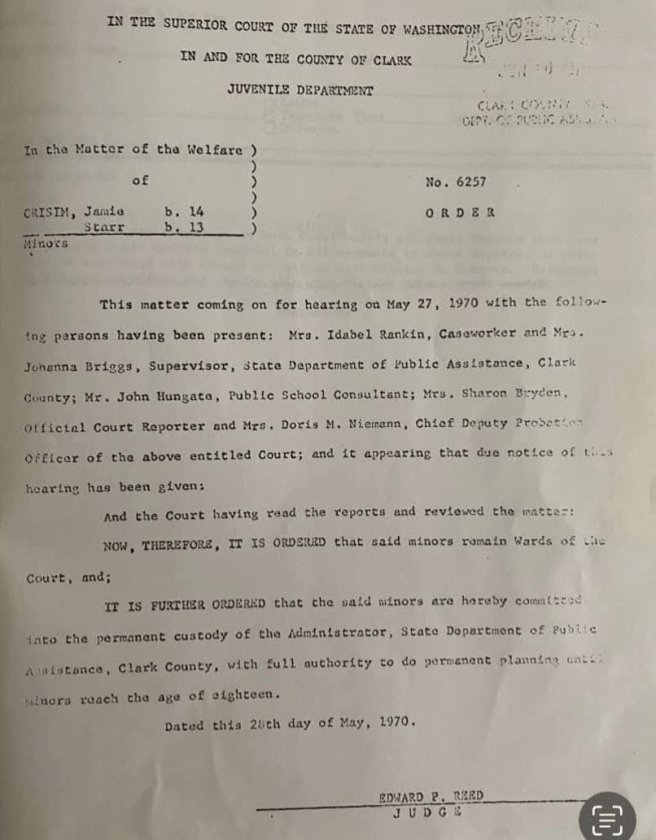

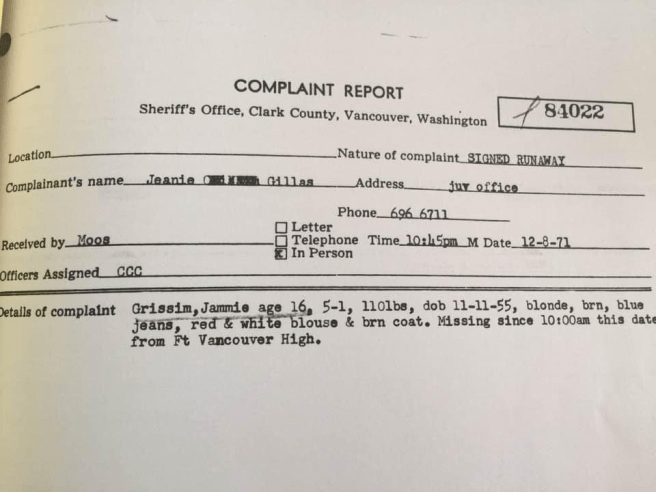

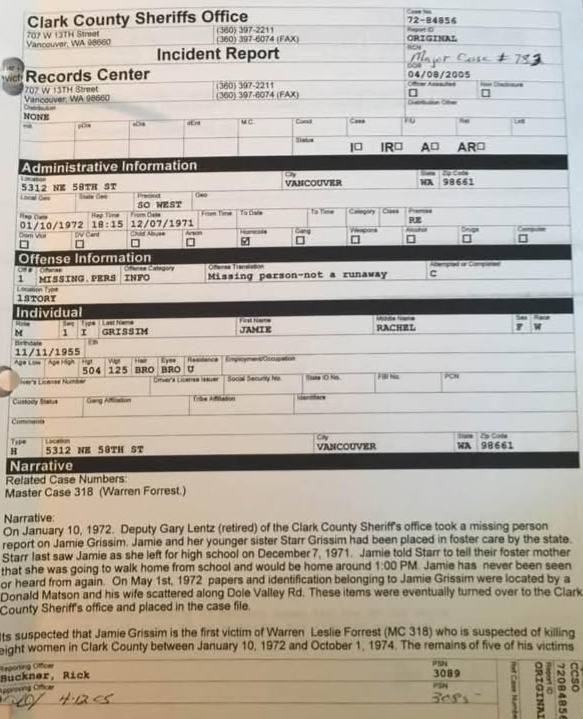

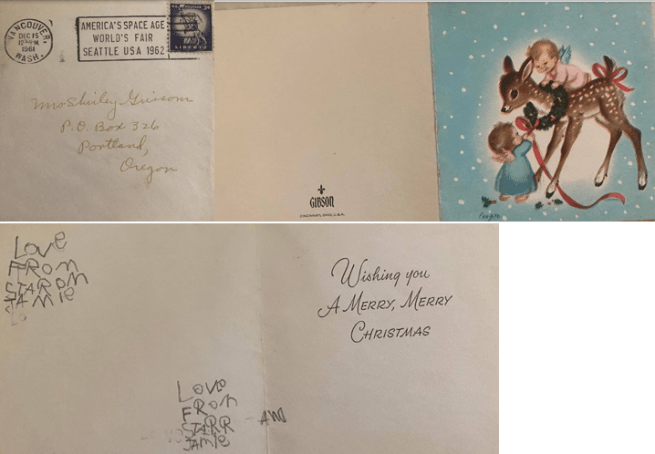

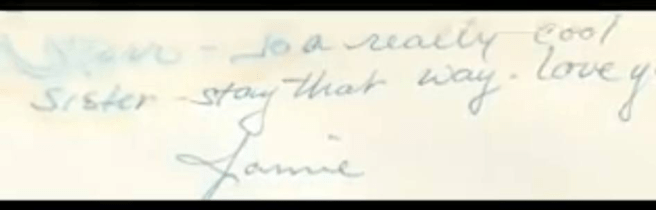

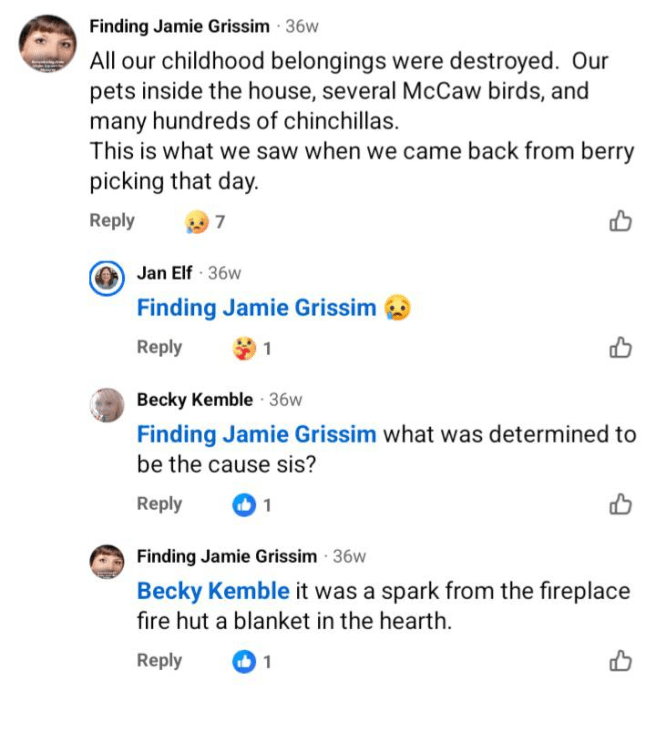

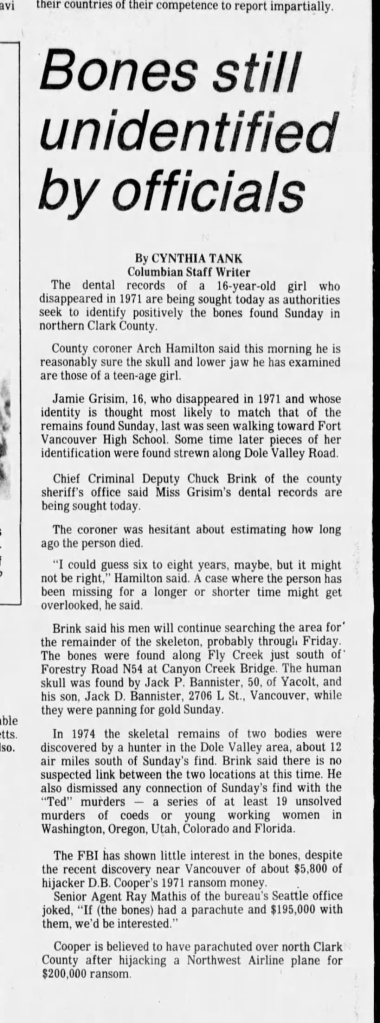

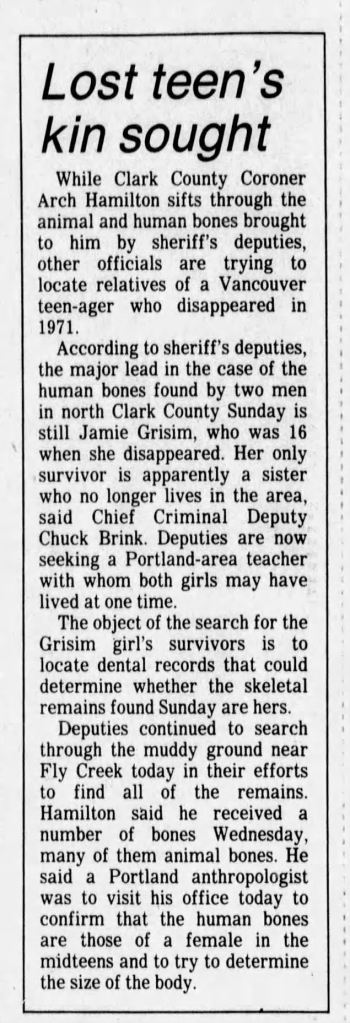

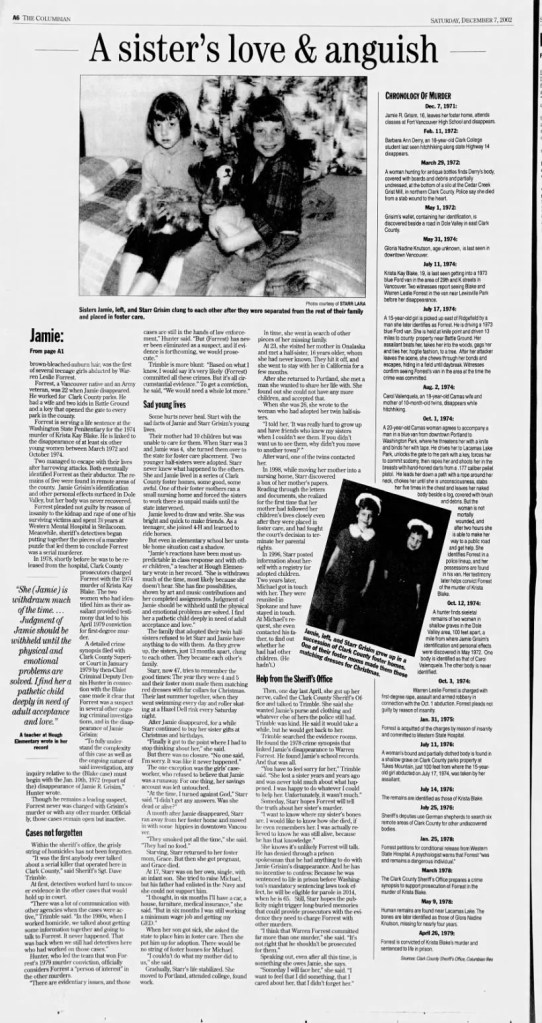

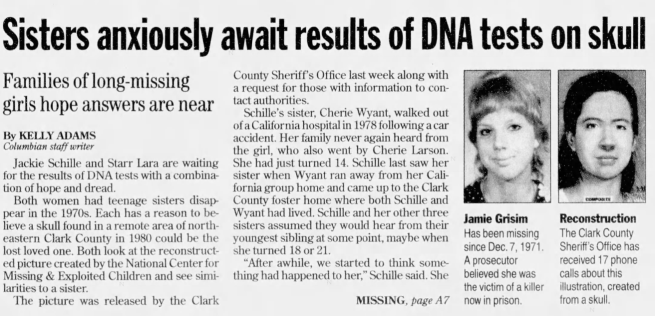

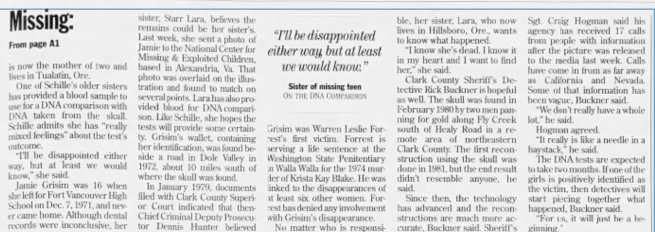

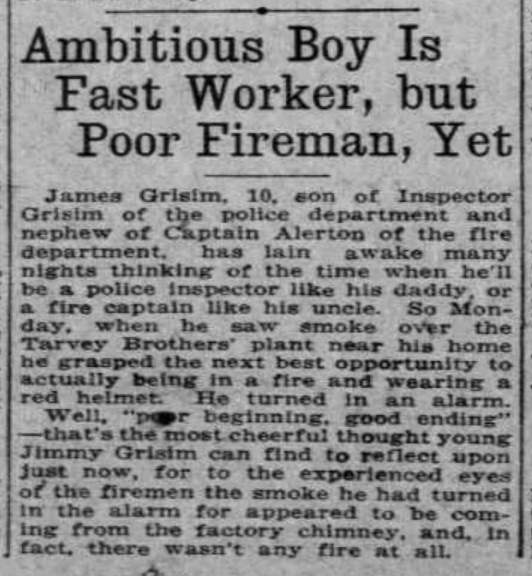

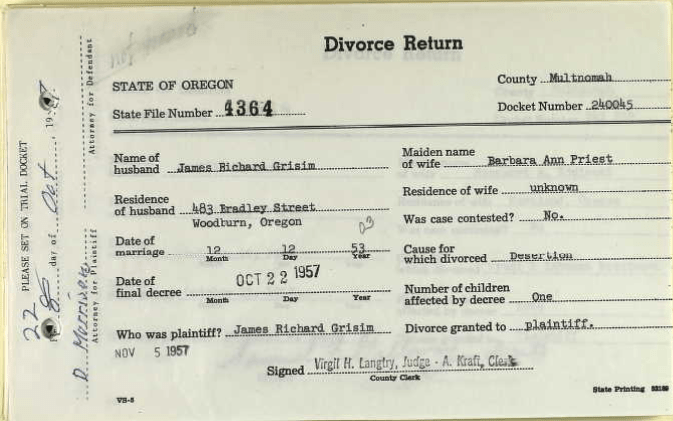

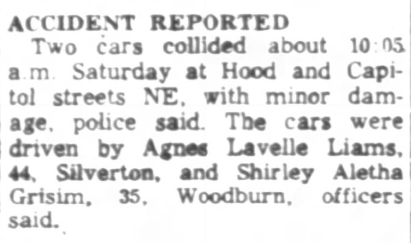

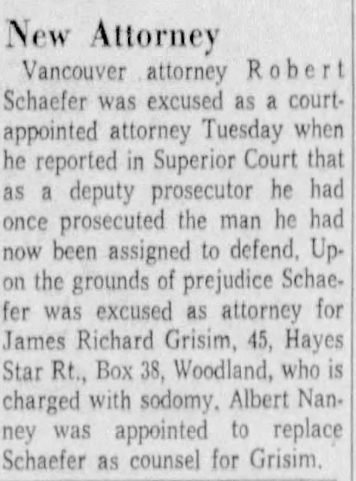

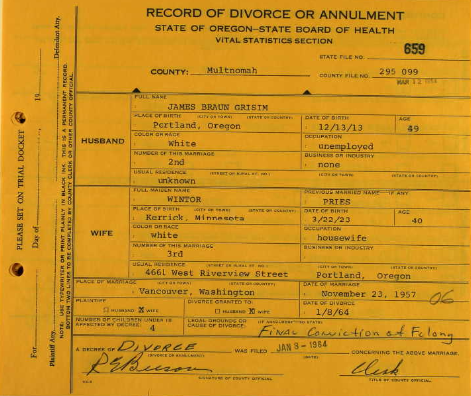

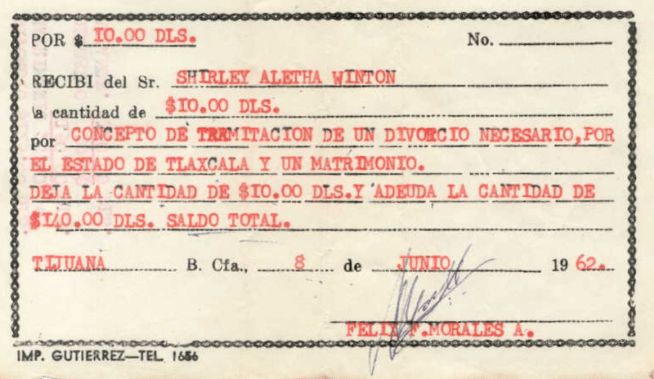

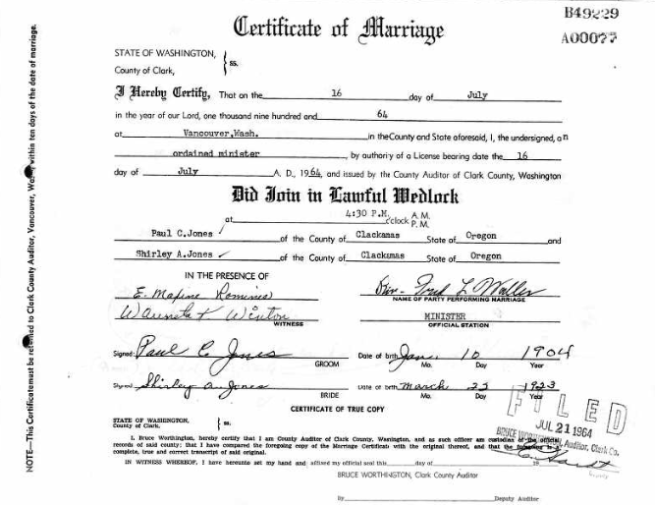

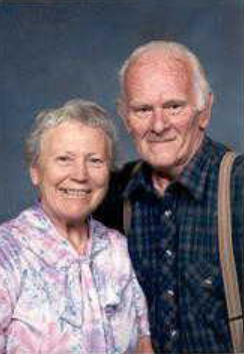

Possible Victims: On December 7, 1971 sixteen-year-old Jamie Rochelle Grisim was last seen walking home from Fort Vancouver High School; she was reported as missing by her foster mother the following day. During one of the searches for her shortly after she disappeared, detectives came across quite a few of her personal belongings in Dole Valley, including her purse and an ID card. It was initially believed that she ran away from her foster home and left the state, but that theory was quickly disregarded. Since Martha Morrison and Carol Valenzuela were later recovered not far from where her belongings were found, local LE have reassessed their conclusions and now feel that Jamie was abducted and killed by Warren Forrest.

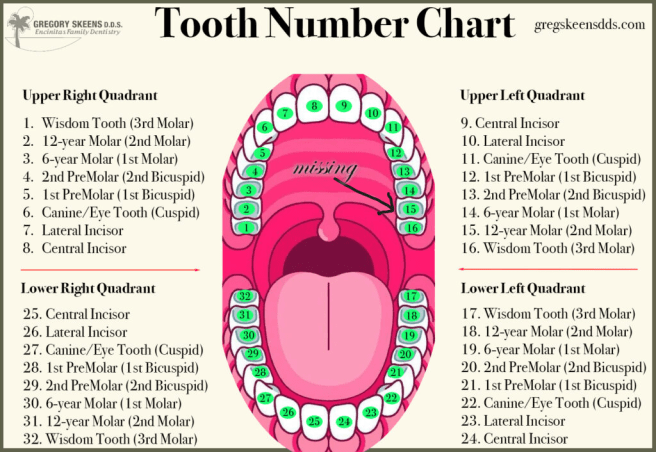

Eighteen-year-old Clark College freshman Barbara Ann Derry went missing on February 11, 1972, and was last seen on a Vancouver highway trying to hitchhike along State Highway 14 East and had been trying to make her way home to Goldendale. Tiny in structure, Derry was only 5’1” tall and weighed a mere 115 pounds, and at the time of her murder had been living on ‘W’ Street in Vancouver. Her remains were discovered later that year on March 29 covered with boards and debris at the bottom of a silo inside the Cedar Creek Grist Mill; she had died from a single stab wound to her chest that had been inflicted by a ‘narrow-bladed instrument,’ and had been partially undressed and had been missing her bra. A positive identification was made thanks to dental records, and it was said she had ‘many male friends,’ and was known to hitchhike frequently. Coincidentally, Derry’s body was found near the area where a large manhunt had been underway for ‘DB Cooper,’ an unidentified skyjacker that jumped out of a plane with a $200,000 ransom (his fate remains unknown to this day despite extensive investigations).

Either Forrest has some incredible self-restraint, or he has some victims that are unaccounted for (I suspect the latter): well over two years passed between the murder of Barbara Derry and the disappearance of Forrest’s next unconfirmed victim, fourteen-year-old Diane Gilchrist. A ninth-grader at Shumway Junior High School in Vancouver, Gilcrest went missing on May 29, 1974 and prior to her disappearance had never showed any problematic behaviors: her parents said she had left their home in downtown Vancouver through her bedroom window on the second floor then vanished into the night, never to be seen or heard from again. As of February 2026, she has never been found, and her fate remains unclear.

Nineteen-year-old Gloria Nadine Knutson was last seen by several acquaintances at a Vancouver nightclub called ‘The Red Caboose’ on May 31, 1974 after turning down an invitation to a housewarming party. One eyewitness told investigators that the Hudson Bay High School senior had sought out his help in the early morning hours, saying that somebody had tried to rape her and was now stalking her; he also reported that she had asked him to drive her home, but his car had been out of gas. Distraught and out of options, Knutson was forced to walk to her residence and disappeared immediately after; her skeletal remains were found by a fisherman in a forested area near Lacamas Lake on May 9, 1978.

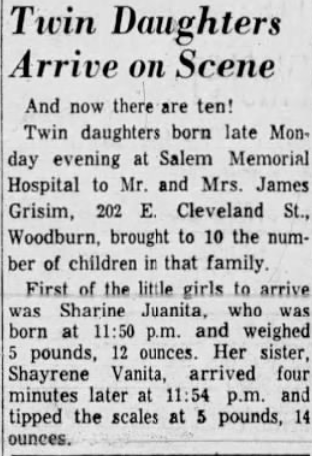

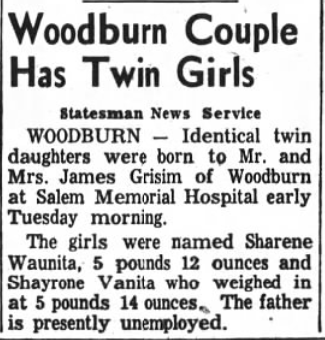

On August 4, 1974 married mother of infant twins Carol Louise Platt-Valenzuela went missing while attempting to hitchhiking from Camas to Vancouver; the twenty-year-old was not known to be involved in prostitution and had no criminal record. On October 12, 1974 her skeletal remains were discovered by a hunter in the Dole Valley outside of Vancouver, very close to those of Martha Morrison, and because of this, detectives strongly suspect Forrest is responsible for the murders of both young women.

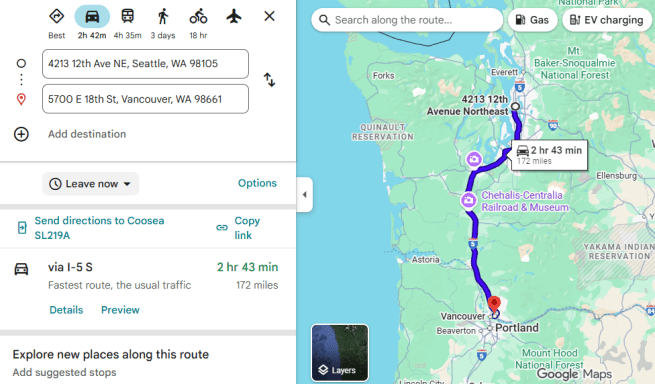

Lesser Discussed Possible Victims of WLF: There are a few additional possible victims of Warren Leslie Forrest that aren’t frequently discussed that do fall in that 1973 gap of inactivity: Rita Lorraine Jolly disappeared out of her West Linn, OR neighborhood while out on a routine nightly walk on June 29, 1973; her remains have never been recovered. It’s worth noting that West Linn is only a fifty-minute drive from Battle Ground, WA (where Forrest had been living at the time with his family).

On August 20, 1973 twenty-three-year-old seamstress Vicki Lynn Hollar was walking out of The Bon Marche in Eugene, which was her new POE (she has only been there for about two weeks, and was a transplant from Flossmoor, IL). She had walked out to her black 1965 VW Bug with her supervisor, and it was the last time she was ever seen alive. Hollar was supposed to show up at home to go to a party with a friend later, but never arrived. Neither her nor her vehicle have ever been recovered. It is slightly over a two hour drive from Battle Ground to the Macy’s that Hollar worked at in Eugene.

On November 5, 1973 Suzanne Seay-Justis was last heard from when she called her mother from a pay phone outside of The Memorial Coliseum in Portland; she told her she would be home the following day so she could pick up her young son from school, and despite having her own car Justis hitchhiked to Portland. The Memorial Coliseum is only a half hour drive from the Forrest family home on SW 18th Street in Battle Ground.

Washington state detectives have never stopped looking into Forrest in regard to the murders that he stands accused of committing, and in December 2025 were able to locate a long-lost witness in relation to the murder of Jamie Grisim. Additionally, they’re working with the ‘Washington State Search Team and Rescue’ as well as ‘Clark County Search and Rescue’ and have plans for another search in the Dole Valley area, this time using dogs that are highly trained in locating human remains that could be decades old and buried deep underground.

Conclusion: James Allen Forrest died at the age of thirty-four on November 24, 1980 after succumbing to ‘a lengthy illness.’ According to his obituary, he was unmarried at the time of his death and was ‘formerly a member of the Junior Odd Fellows;’ he was also the Past Chief Ruler of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows No. 3 at St. John’s Road. Warren’s father Harold died of leukemia at the age of seventy-three on October 13, 1991 in Portland. According to his obituary, before he retired Harold was the foreman of the labor force at the Vancouver Veterans Hospital for thirty-five years and was a member of the Washington Gateway Good Sam Travel Club (as he was an avid traveler). Delores Beatrice Forrest died at the age of seventy-seven on Christmas day in 2002 in Walla Walla.

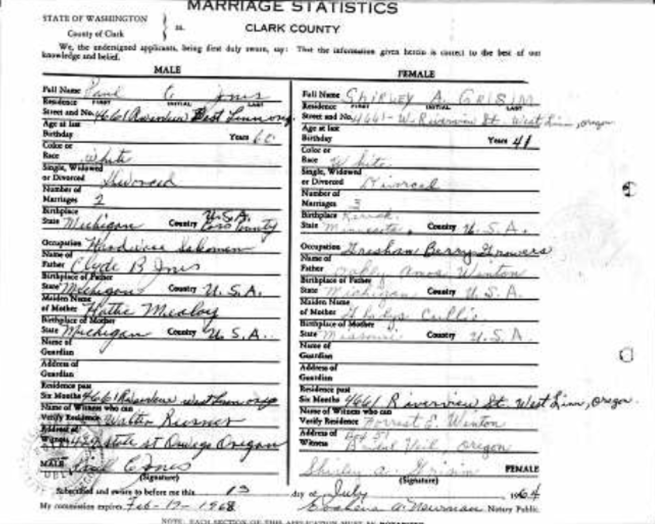

Marvin Forrest married Diane Steigleman at the age of forty-eight on July 23, 1996, but sadly not even four months later on November 23, 1996 he was killed in a plane crash above the Pacific Ocean roughly forty miles from the Northern California coast; his body has never been recovered. According to his obituary, Marvin worked at the Portland Air Base as a civilian mechanic, and he was a proud member of the Air Force Reserve; he was also a member of the First Church of God. Marvin and Diane both liked old cars and were looking forward to retiring in 2002 and traveling together. He had a son and a daughter, and his widow is now happily retired and living in Lake Havasu City, AZ.

Warren’s younger child Lane is married to his wife, Monica and the couple have three children together; he works at Boeing Commercial Airplanes in Seattle as a mill operator. His daughter Leslie is fifty-four and currently resides in Bullhead, AZ; sadly she is suffering from a plethora of health concerns, including three inoperable brain tumors.

As of February 2026, Warren Leslie Forrest is seventy-six years old and is housed at Airway Heights Corrections Center in Spokane County, WA. He is still married to his second wife Hilda Ruchert, a nurse that he met while incarcerated and wed on June 20, 1983 who is fifteen years his senior (she was born on September 12, 1934). One of the only things I was able to find out about her is that she was born on September 12, 1934 and according to an article published in 2017 on ‘koin.com,’ was in her 80’s, and still residing in Walla Walla; I could find no record of her death. Sharon Ann Forrest got remarried to a man named Jim Lochner on November 11, 2011, and the couple currently reside in Vancouver, WA; she is retired after a long career of working in the administrative part of a doctor’s office.

Works Cited:

‘Cold Case Team Analyzing Evidence that May Link More Women to Serial Killer Warren Forrest.’ (December 11, 2024). Taken January 6, 2026 from forensicmag.com

Fox 12 Staff. ‘Clark County renews search for missing Teen Tied to 1970’s Serial Killer.’ (December 5, 2025).

Iacobazzi, Ariel & Plante, Aimee. ‘Cold Case Team Revisits Death Linked to Warren Forrest Plante.’ (December 9, 2024). Taken January 6, 2026 from koin.com

Nakamura, Beth. Warren Leslie Forrest Clark County murder trial begins. Taken January 6, 2026 from oregonlive.com

Varma, Tanvi. ‘Authorities believe multiple cold cases are linked to suspected Clark County serial killer.’ (December 10, 2024). Taken January 6, 2026 from katu.com

‘Warren Forrest.’ Taken January 6, 2026 from grokipedia.com/page/Warren_Forrest