Pitkin County District Court, no. C-1616: THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF COLORADO v. THEODORE ROBERT BUNDY, MOTION FOR CERTIFICATE OF JUDGE REQUESTING ATTENDANCE OF OUT-OF-STATE WITNESS PURSUANT TO C.R.S. 16-9-203, 1977).

Thurston County Sheriff’s Office, documents related to their investigation into William Earl Cosden Jr., Part Three.

Document from the King County Sheriff’s Department: Part One.

I recently put in a request with the King County Sheriff’s Department for information related to the Bundy investigations, and they’ve sent me a lot of stuff and will most likely send a lot more int he future. I’m working on putting the pictures in a blog post, and it’s proving to be exhausting due to the fact that there are SO many of them (I’m working as fast as I can with two jobs and a needy husband). Here are some interesting documents they sent me that are worth a read. I’ve never encountered them out in ‘the wild.’

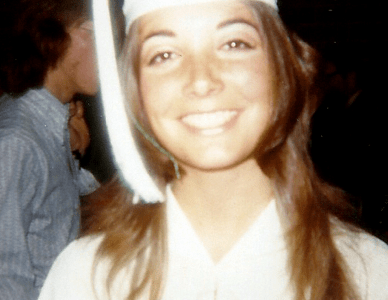

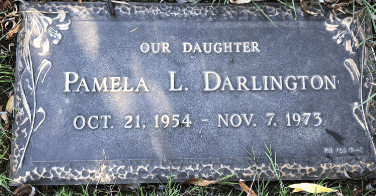

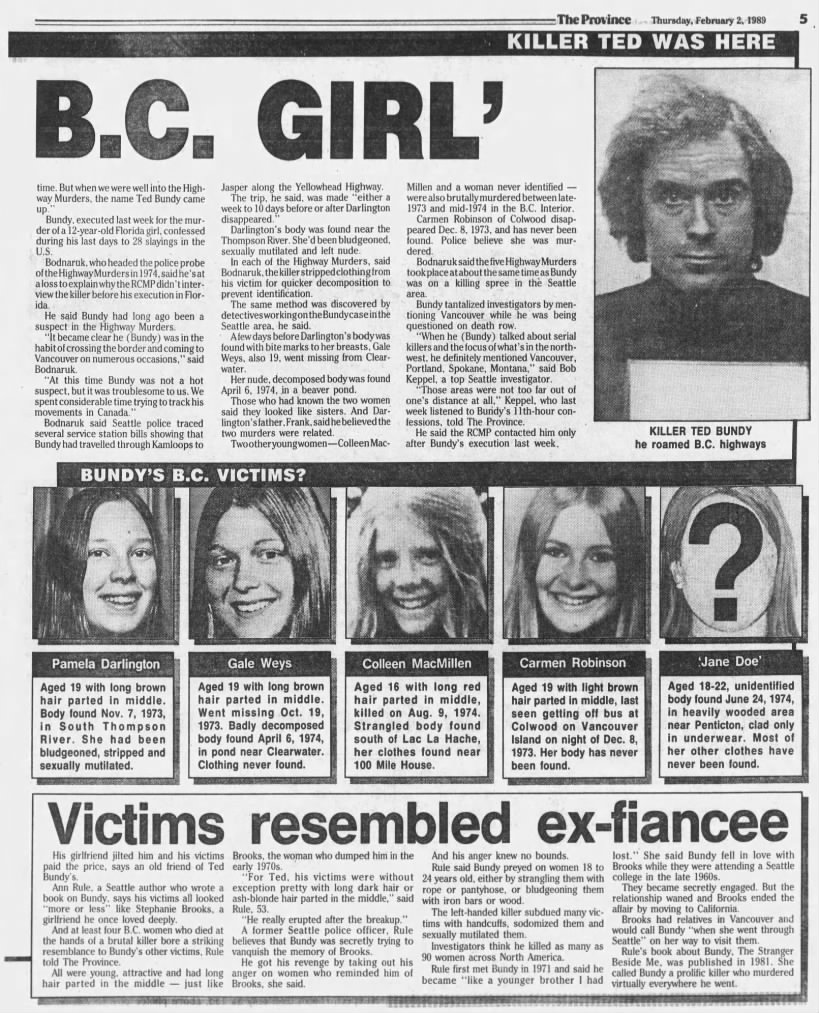

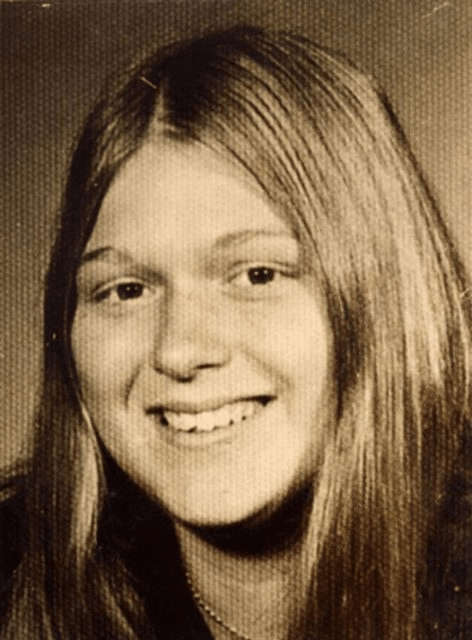

Pamela Lorraine Darlington.

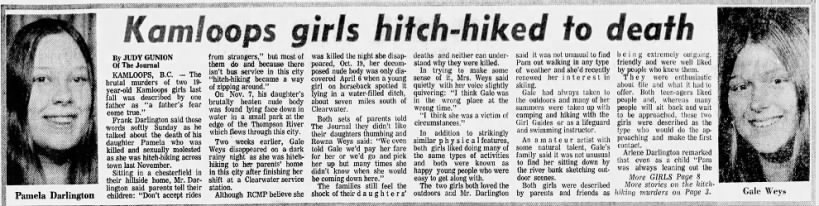

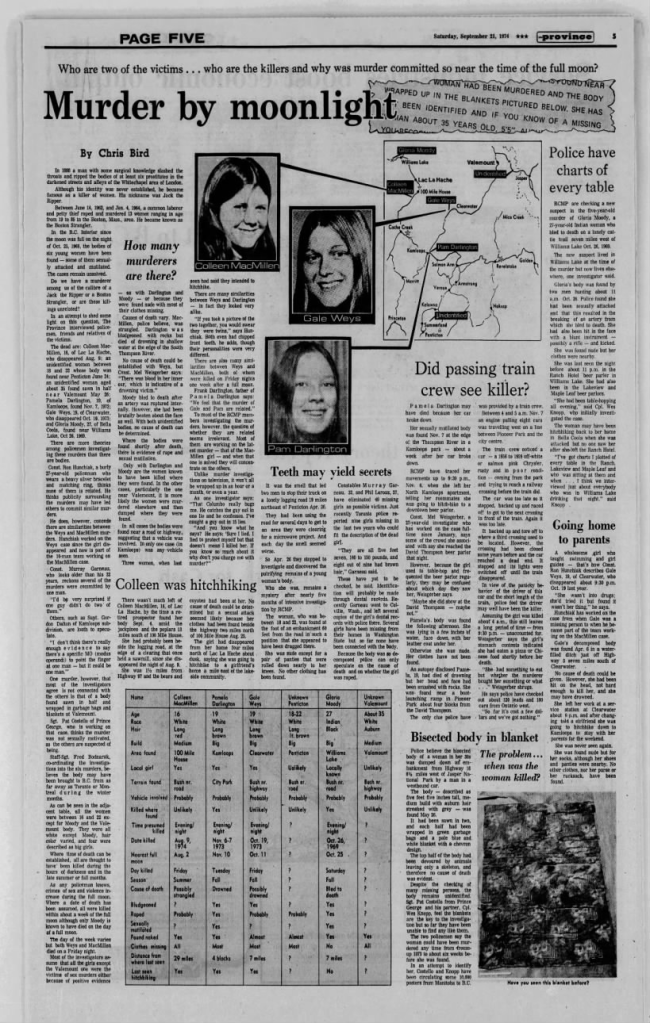

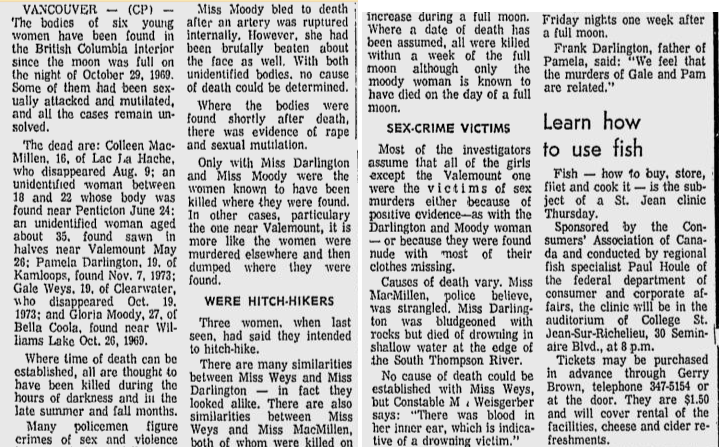

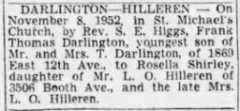

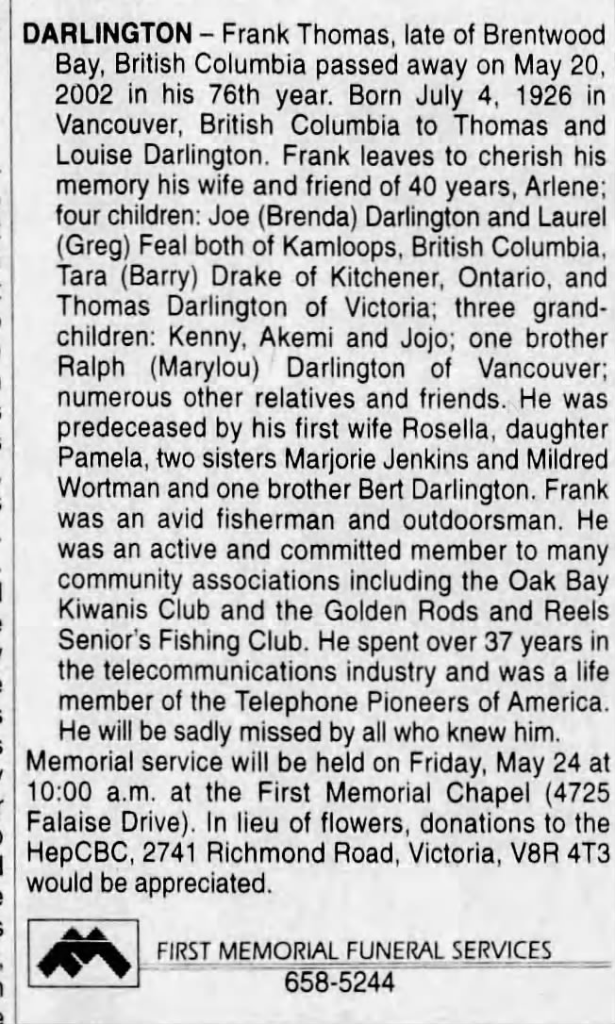

Background: Pamela Lorraine Darlington was born on October 21, 1954 to Frank and Rosella Shirley (nee Hilleren) Darlington in British Columbia, Canada. Frank Thomas Darlington was born on July 4, 1926 in Vancouver, and Rosella was born on June 11, 1928 in Calder, Saskatchewan. The couple were wed on November 8, 1952 at St. Michael’s Church in Vancouver, and had three children together: Pamela, Joseph, and Tara. Sadly, Mrs. Darlington passed away at the age of thirty-three on June 14, 1961; Frank remarried a woman named Arlene Ilvi Moisio and the couple had a son together named Thomas. At the time of her murder, Pamela wore her blonde hair at her shoulders and according to an article published in a British Columbia based newspaper, she weighed 120 pounds and stood at 5’5″ tall; she had been employed as an operator at BC Telephone for roughly one year.

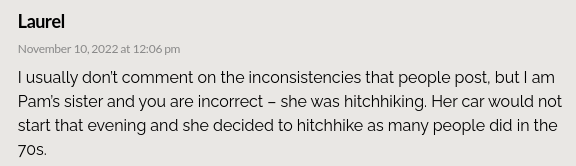

According to an (unidentified) newspaper article published in November 1973, Ms. Darlington was last seen hitchhiking towards Kamloops on Tranquille Road in front of the Village Hotel at around 10:30 PM on Tuesday, November 6, 1973. While investigating, I learned that there is a bit of uncertainty surrounding her final few hours of life: according to her sister Laurel, when she realized her car wouldn’t start she decided to hitchhike into town to meet up with some friends, as it was common back thing to do at that time and everyone did it. However, in an interview with true crime blogger ‘Eve Lazarus,’ Pam’s cousin Sharon said that friends told the Darlington family that she was at The David Thompson Pub sometime in the evening in the company of an attractive (but unknown) gentleman with ‘shaggy hair.’ She added that her ‘cousin Joe (Pam’s brother) always thought it was someone who Pam knew, who was infatuated with her, who committed suicide a year after she died.’

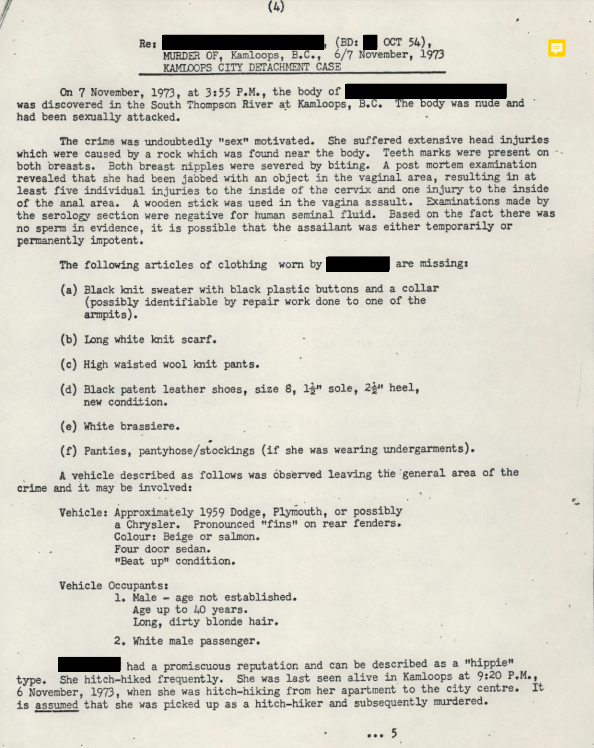

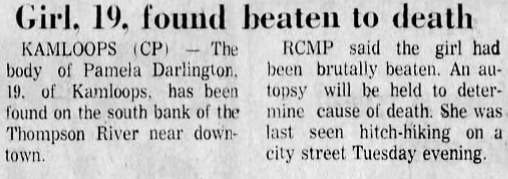

Murder: at roughly 3:30 in the afternoon on Wednesday, November 7th, 1973 Darlington’s remains were discovered in shallow water on the south bank of the Thompson River by seventeen-year-old Frank Almond, who had been out walking with his dog at a nearby park when the animal veered off towards the river that flowed nearby: ‘The dog kinda ran up to something and it looked like a body, so I kinda got a little nervous.’ Almond immediately returned home and told his father what he had seen, and together they went back to where the young woman was lying face down in the riverbed: ‘he came back, he was kinda white as a ghost and he said, ‘Yup that’s a body.’ So we went back and called the police.’ Investigators said that the young woman had been brutally beaten and had been sexually assaulted, and according to an article published in The Times on October 15, 1974, she had been hit in the head with rocks but ultimately died of drowning, and was found with bite marks on her breasts.

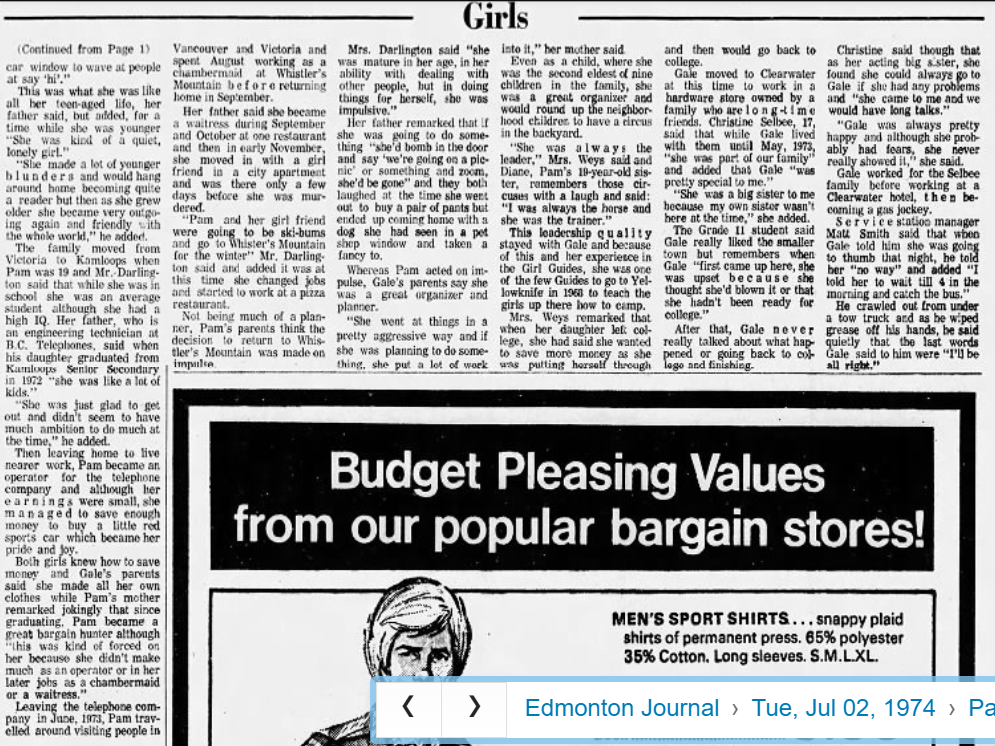

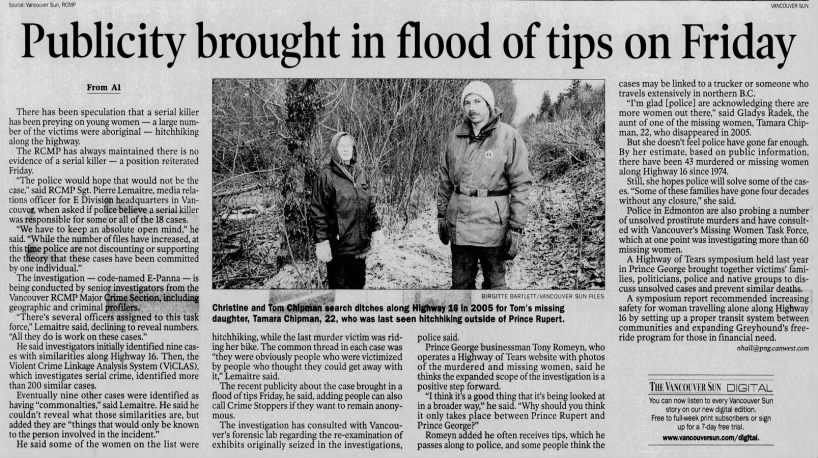

About her cousin, Sharon Darlington said that she was an outgoing person that loved her friends and family and was always laughing: ‘it was many years ago, but I remember it like yesterday.’ … ‘When we were little, I was shy and reserved. Pam wasn’t scared of anything,’ In the initial years following the murder Ms. Darlington said that her family were told by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police that they suspected that none other than Ted Bundy had murdered Pamela, and they were ‘relieved when he was put to death;’ it wasn’t until years later that they learned her case was a small part of an investigation being conducted by the RCMP’ E-Pana Task Force that was set up to look into the eighteen murders and disappearances of female victims along the ‘Highway of Tears,’ a stretch of highway in BC that is notorious for disappearances and murders of women (particularly Indigenous ones) beginning in 1969. Darlington met all three of the task force’s criteria for a victim: she was hitchhiking (which they considered to be ‘high risk activity’), was found near Highway 16/97/5, and was most likely killed by a stranger.

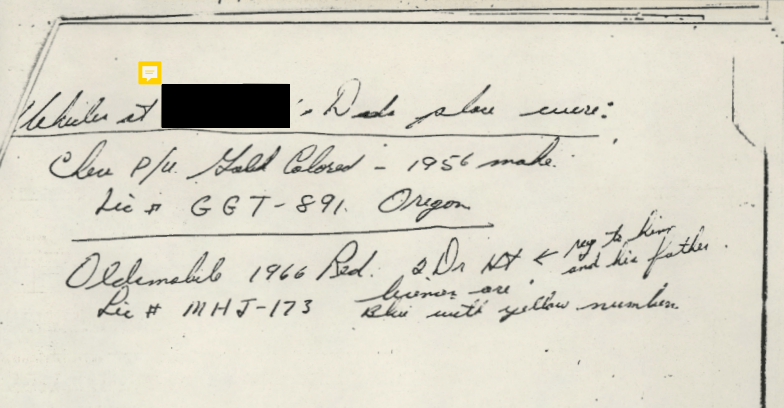

Retired RCMP Constable David Sabean said that Pam’s case remains a priority among unsolved cases, and that ‘there was a big list of suspects, never anyone who came out of it, though.’ At approximately 4:30 AM on the morning that her remains were found a late 1950’s, off-white, four-door sedan in poor working condition was seen leaving the boat launch area near to where her remains were discovered; the male driver was described as having long brown or blond hair and he may have been passengers with him. The vehicle nor its driver have ever been identified and as of April 2025 remain of interest.

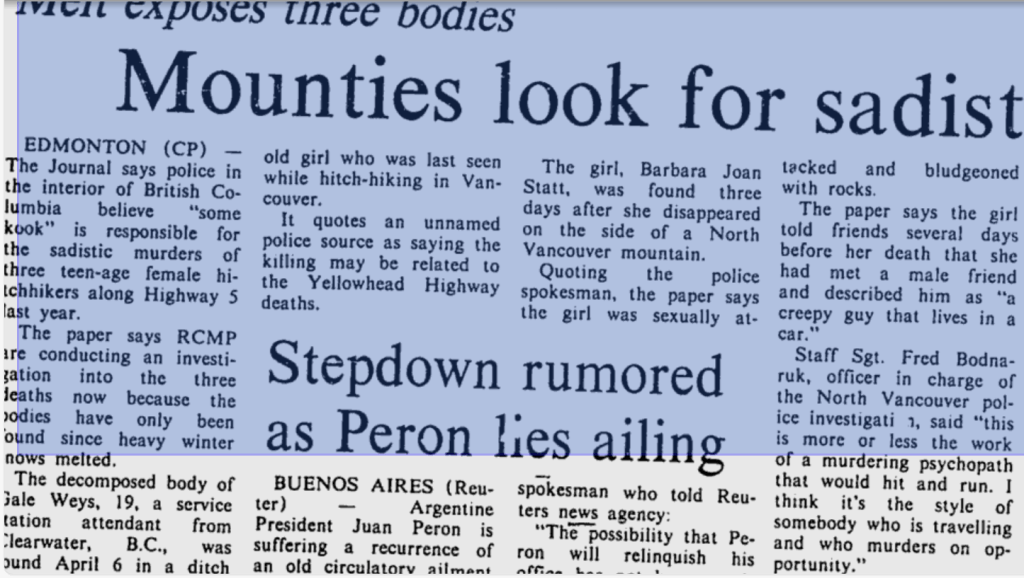

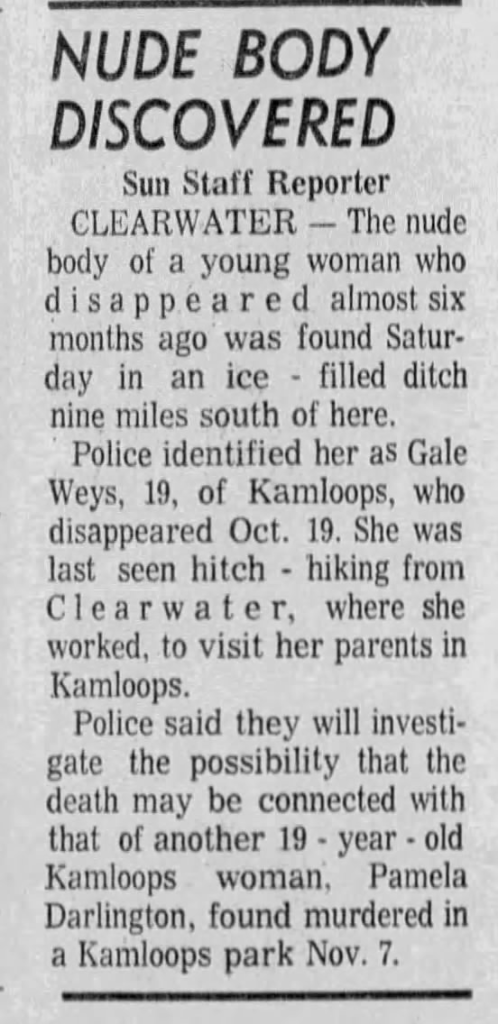

Gale Ann Weys: Less than three weeks before Pam Darlington’s murder, on October 19, 1973 the body of nineteen-year-old Gale Weys was recovered after she disappeared while hitchhiking to her parents’ house in Kamloops from her residence in Clearwater after she finished her shift as an attendant at a local gas station; her remains were discovered six months later in a ditch along Highway 5.

On the evening Weys disappeared a local banker named Ron Hagerman told investigators that he ate a meal at The Thompson Hotel where she worked, and she shared with him her plans to hitchhike the more than 75 miles to her parents house in Kamloops. He also reported that he observed she had been asking around the bar if anyone would have been able to give her a ride: ‘I know that night she was asking around for someone to drive her to Kamloops because her parents lived there. No one was going to Kamloops, and so she just walked outside and stuck out her thumb.’ It is strongly speculated that she may have instead went north of Quesnel after some reports claimed that she had been trying to hook up with the staffing agency ‘Canada Manpower Centre,’ but nothing ever came of this. Her remains were discovered in a water-filled ditch on April 6, 1974 off Highway 5, roughly seventy-eight miles north of Kamloops; according to law enforcement, her clothing was never recovered.

The second of nine brothers and sisters, Gale’s siblings recall her as being an independent, funny, and protective big sister that spent her time spare time working as a lifeguard and Girl Guide leader. She had recently moved to Clearwater and was working two jobs at the time of her murder to help save for college, and volunteered at a local school helping care for special-needs children. According to her mother Rowena, she was also a swimming instructor and often took trips with the scout group that she helped lead, and at the time of her death was saving for a vacation to Mexico. Mrs. Weys recalled that her daughter was a wonderful and upbeat young woman, and her Uncle Ted said that she was kindhearted, and: ‘was a hell of a nice girl, very outgoing and friendly.’ He also commented that his niece and Colleen MacMillen looked so similar that they could have been mistaken for sisters (more on Colleen in a bit).

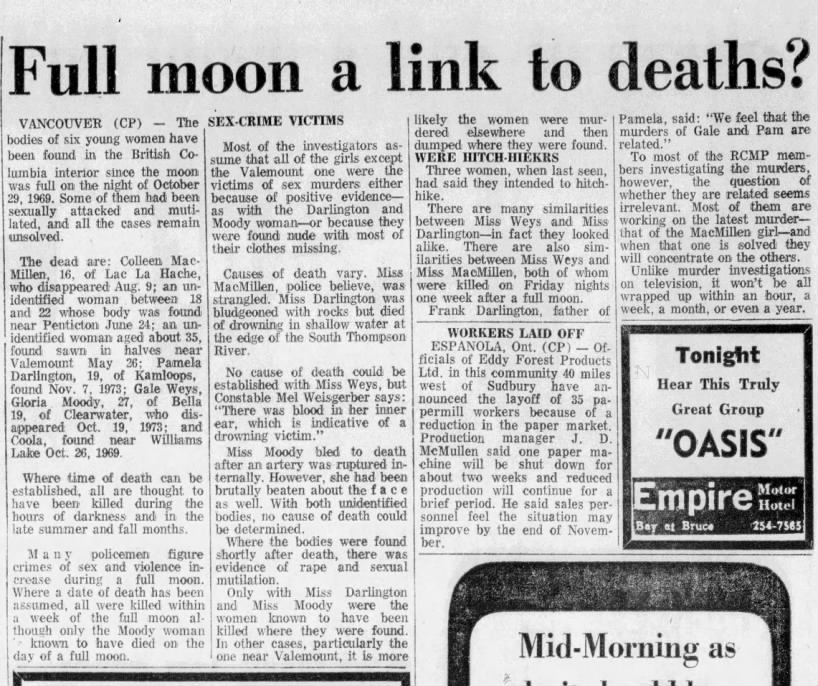

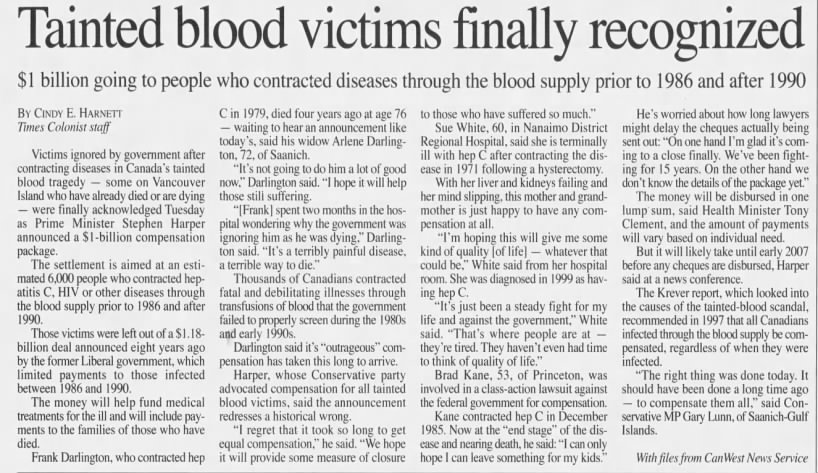

Both the Weys’ family as well as the Darlington’s felt that their daughters’ murders were not ‘personal,’ and were more ‘crimes of opportunities’ versus passion; they also felt that there could have been some connection in the murders due to some striking similarities in the girls’ appearance as well as the circumstances surrounding their deaths. Shortly after Pam’s death Frank Darlington said he strongly believed they were more than just murders in a city by a lone psychopath, and ‘for all we know, this could be a Manson-type murder,’ and that the slayings were most likely committed by ‘a psychopath.’

Colleen MacMillen: On September 4, 1974 the remains of sixteen year old Colleen Rae MacMillen were discovered roughly thirteen miles south of 100 Mile House, a district municipality located in the South Cariboo region of central British Columbia. MacMillen was born on April 11, 1958 in Kamloops, BC and had left home on August 9 with plan to hitchhike to a friend’s house a few miles away; she was reported missing by a member of her family two days later when they realized she never made it to her destination. Although newspapers said MacMillen was going to see a girlfriend, ‘The 100 Mile Press’ reported that she was on her way to meet up with her boyfriend when she disappeared.

MacMillen’s clothes were discovered at Mile 102 on Highway 97 on August 25, 1974 by a tourist even though her nude body wasn’t discovered until early September (she was completely naked except for her socks). One of seven brothers and sisters, her father knew that she would never run away because she ‘wasn’t that type of girl:’ ‘She was a quiet sort of girl, not what you would call a bubbly effervescent type of girl but very friendly.’ Retired Staff Sergeant Fred Bodnaruk with the North Vancouver RCMP said that hair samples were taken from a suspicious 1966 Meteor Montcalm that was found abandoned near 100 Mile that did not match MacMillen’s, and the vehicle had a crumpled right fender that may have been the result of an accident that took place after it was stolen. Although no cause of death could be determined, (retired) RCMP Constable Mel Weisgerber said that there was blood in MacMillen’s inner ear which is ‘indicative of a drowning victim.’

At the time of her death, MacMillen had a twenty-one year old boyfriend named Ron Musfelt, who came out in recent years and said that he ‘lived under a cloud of suspicion for many years:’ ‘I was going out with Colleen, and one night I phoned her, and I was talking to her, and she said ‘meet me down Lac Le Hache.’ So I went down the highway to wait by K&D General Store. I went back up to the house, and phoned her house and they said she had already left. And I waited and waited and waited and waited, and she never showed up.’ For years after Colleen’s death Musfelt was a key suspect in her murder, and he ‘was taken into town and they interrogated me, and they did everything to me. Lie detector tests, everything like you wouldn’t believe, and to this day it’s always bothered me, never knowing who did it. I remember back then there were probably people who thought I had something to do with it.’ … ‘The thing that really bothers me is knowing I was standing on the highway, waiting for her to come through town, and she probably came past me in this vehicle, with this guy, wanting to get out of his vehicle.’

About the death of his sister, Shawn MacMillen said that Colleen was ‘a lovely, sweet, innocent sixteen-year-old kid and there are no words to express how terribly she was wronged.’ Regarding Colleen, Pam, and Gale’s death, Frank Darlington said he believed that it was more than just a murder in a city by a lone psychopath, and that ‘for all we know, this could be a Manson-type murder,’ and he feels sure the killings were done by a psychopath. On September 25, 2012, it was announced by the RCMP that DNA taken from MacMillen’s clothes matched with a man named Bobby Jack Fowler, who managed to fly under the radar until his arrest in 1995.

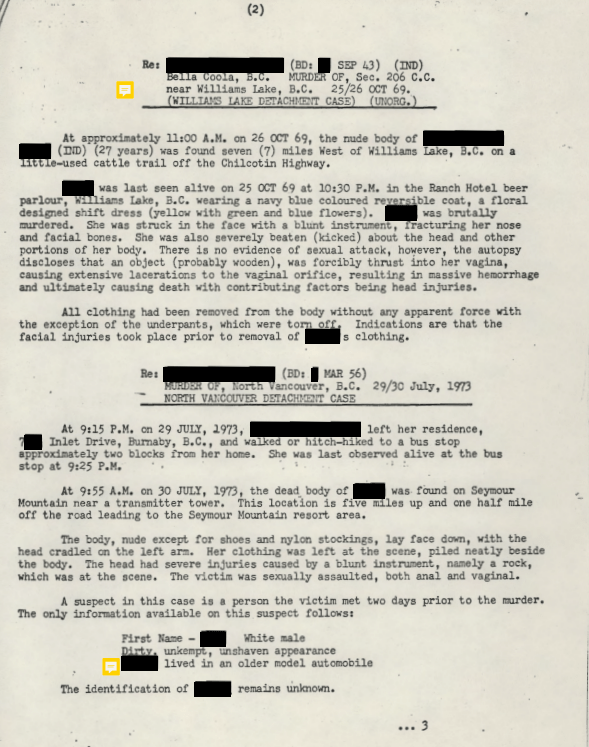

Barbara Joan Statt: A name that only came up once during my research is Barbara Joan Statt, who was only seventeen when she was last seen hitchhiking in Vancouver on July 26, 1973. Her remains were discovered three days later on the side of a mountain in Northern Vancouver; she had been sexually assaulted and had been hit on the head with a rock (that was found nearby). Friends told law enforcement that right before she was killed, Statt told them that she’d met a new male friend, but they referred to him as the ‘creepy man that lives in a car.’

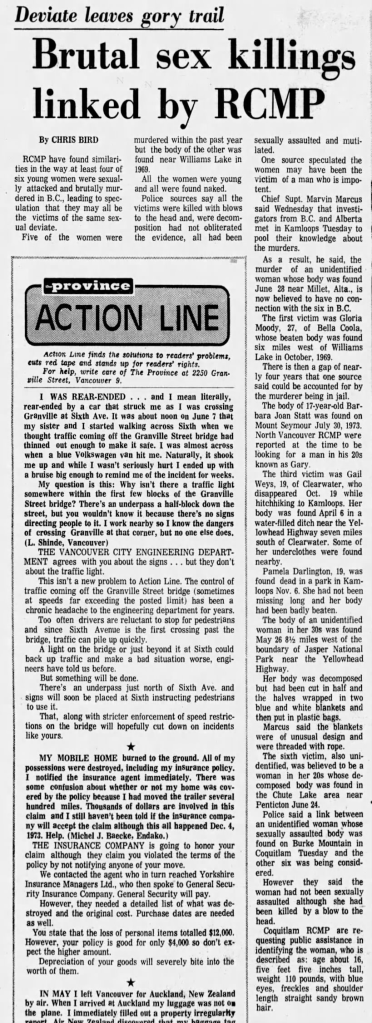

Statt’s homicide was investigated in relation to the three others (Darlington/Weys/MacMillen) that took place along Highway 5 in BC in 1973/74. Sergeant Bodnaruk described the killer as a ‘murdering psychopath that would hit and run,’ and in the beginning stages of the investigation it made sense that she was included with the other victims: like two of the three others, Barbara was sexually assaulted and was of similar height and build, however I quickly learned that there was a good reason why she wasn’t included more frequently: it was quickly determined that a Toronto resident named Paul Cecil Gillis was responsible for her death, who was apprehended for her murder in 1974. He was also convicted of killing fifteen-year-old Robin Gates of Coquitlam, and thirty-three-year-old Lavern Johnson.

Gloria Moody: Another name I came across is Gloria Moody, who was only twenty-seven when she was killed during a weekend away with her family on October 25, 1969. A member of the Bella Coola Indian Reserve with the Nuxalk Nation in British Columbia, Moody’s body was found a day after she disappeared by hunters on a cattle trail roughly six miles west of Williams Lake. Her autopsy report said that she bled to death after being beaten and was sexually assaulted, and she is the oldest unsolved murder in Project E-Pana.

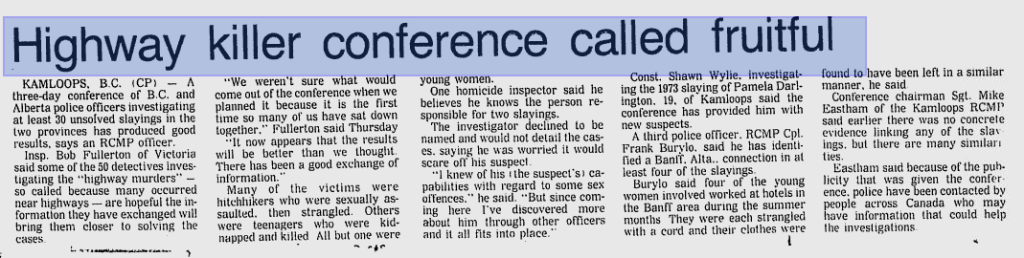

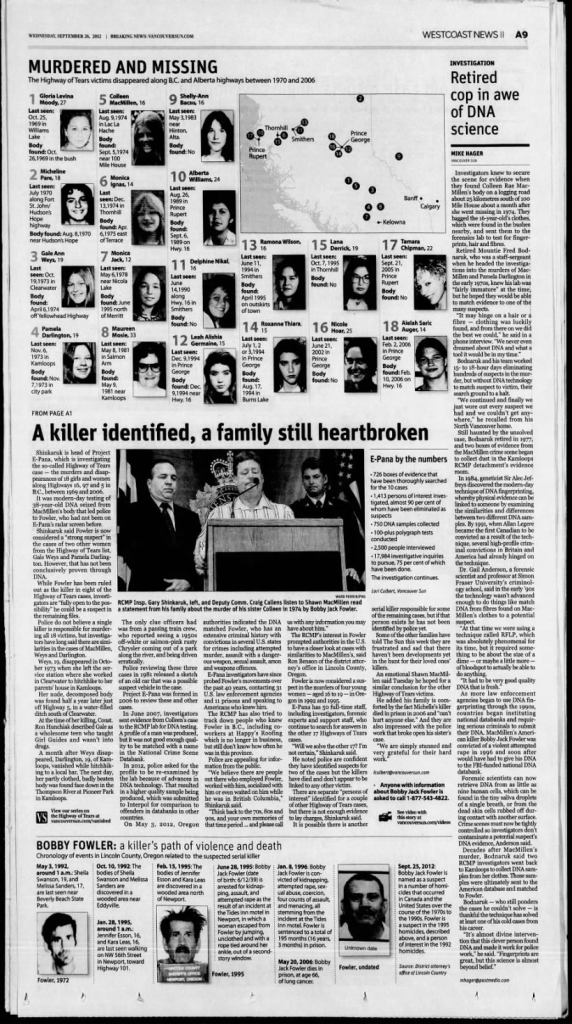

The ’Trail of Tears:’ Pamela Darlington, Gale Weys, and Colleen MacMillen are just three of (at least) eighteen missing and murdered women that are being investigated by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police ‘E-Pana Task Force’ that focused on the infamous ‘Highway of Tears,’ a 447-mile stretch of Highway 16 between Prince George and Prince Rupert in British Columbia beginning in 1969. On that list is a disproportionately high number of Indigenous women, hence its association with the ‘Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Movement.’ The exact number of missing and murdered women varies depending on the source: according to RCMP’s E-Pana task force, the count is around eighteen, where Aboriginal organizations estimate the number to be over forty. Wikipedia lists seventy-nine victims, including a family of four so technically that would be eighty-two.

Proposed explanations for the years-long span of disappearances and homicides (along with the limited progress in the case) include poor economic conditions, substance abuse, domestic violence, the foster care system, and Canadian Indian residential school system. Thanks to the high rate of poverty in the area many people were unable to buy a car, and as a result hitchhiking was a common way to travel large distances. There was also a lack of public transportation at one time, and it didn’t help that the area is remote and largely uninhabited; also, it wasn’t until December 2024 that much of the roadway didn’t have cellular telephone signal. Along the highway, soft soil in many areas made discarding a body incredibly easy, and local wildlife only helped.

Bobby Jack Fowler: Convicted serial killer and rapist Bobby Fowler was born on June 12, 1939 to Selva ‘Mutt’ and Oma Lee (nee Hathaway) Fowler, and was active in the US and Canada between 1973 to 1995. On March 6, 1959, he married Theresa Patton and they had five children together: Johnny, Janey, Pam, Loretta and Randell. After he was arrested twice in 1969, Theresa decided that she had enough of his shenanigans and the couple divorced on May 17, 1971, shortly before he moved to British Columbia.

For the most part Fowler was a transient, and worked menial construction jobs all over North America and Canada, and it is confirmed he spent time in Florida, British Columbia, Iowa, Texas, Washington, South Carolina, Arizona, Tennessee Louisiana, and Oregon. An addict in many regards (he was known to abuse a variety of substances, including alcohol, amphetamines, and methamphetamines), Fowler had a criminal record a mile long that included a firearms offense, sexual assault, and attempted murder.

In 1969, Fowler was charged with killing a couple in Texas but was only convicted of ‘discharging a firearm within city limits.’ He did spend some time in a prison in Tennessee for sexual assault and attempted murder because (in the words of the investigating attorney), ‘he tied a woman up, beat the hell out of her with her own belt, covered her with brush and left her to die.’

Bobby was known to drive long distances and enjoyed traveling in ‘beat-up old cars,’ and often picked up transients and hitchhikers along the way. He also spent a lot of time in seedy bars and motels and believed that the young women that he picked up wanted to be hurt, and were somehow asking for it. According to Deputy Commissioner Craig Callens, ‘he believed that the vast majority of women he came in contact with… Women that hitchhike and went to taverns and bars, desired to be sexually assaulted and violently sexually assaulted.’

In addition to Darlington, MacMillen, and Weys, The Royal Canadian Mounted Police also believe that Fowler is either suspected or is considered a ‘person of interest’ in (at least) an additional ten murders (possibly upwards of twenty) between British Columbia and Oregon going as far back as 1969. It’s important to keep in mind that quite a few of the ‘Trail of Tears’ murders took place after he was incarcerated in 1996, and geographic profiler Kim Rossmo said that (in his educated opinion) Fowler is not responsible for any of the deaths along Highway 16 that took place between 1989 and his arrest in 1995. Additionally, it’s worth mentioning that the only thing linking the killer to the area is the fact that he worked for a local roofing company in 1974, called ‘Happy’s Roofing.’

Fowler was arrested on June 28, 1995 after an incident in Newport, Oregon involving a woman jumping out of a second floor window at the Tides Inn Motel with a rope tied to her ankle. Luckily she survived and reported the incident to the local police, and he was arrested and charged. On January 8, 1996 Bobbly Fowler was convicted of kidnapping in the first degree, attempted rape in the first degree, sexual abuse in the first degree, coercion, assault in the fourth degree, and menacing; he was sentenced to 195 months in prison with the possibility of parole.

On September 25, 2012, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police along with Lincoln County DA Rob Bovett named Bobby Jack Fowler as a suspect in the murders of Pam Darlington, Colleen MacMillen, and Gale Weys after it was determined that his DNA was found on MacMillens’ remains. Unfortunately, in May 2006 Fowler died from lung cancer at the age of 66 in Oregon State Penitentiary before he was able to be held accountable for his actions. Colleen’s brother Shawn commented that his family was ‘comforted by the fact he was in prison when he died, and he can’t hurt anyone else.’

In the mid-1970s, newspapers reported that Pams clothes were never found, however Sharon remembers that her dad told her they were discovered folded up near her body. If that’s true, then they are most likely long gone, which is tragic because DNA evidence found on the fabric could have confirmed that Fowler murdered her (or that he didn’t). Despite what the RCMP called ‘similar fact evidence,’ there wasn’t enough direct evidence to conclusively link the killer to the murders of Pam Darlington and Gale Weys, a fact that’s heartbreaking for both families because the cases will most likely remain forever unsolved.

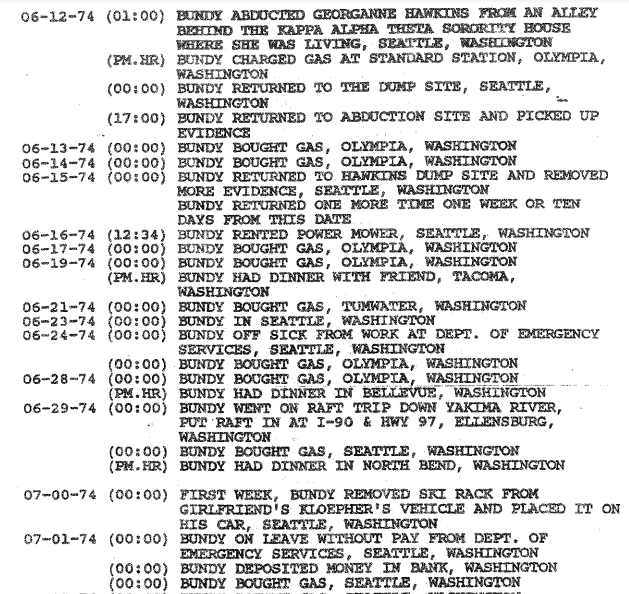

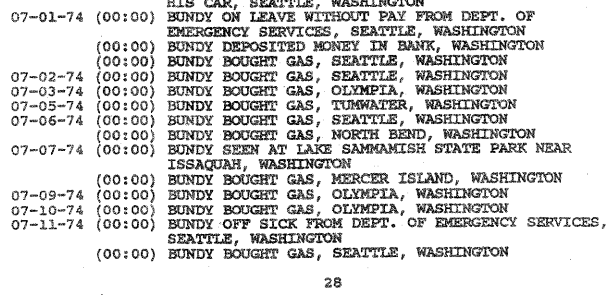

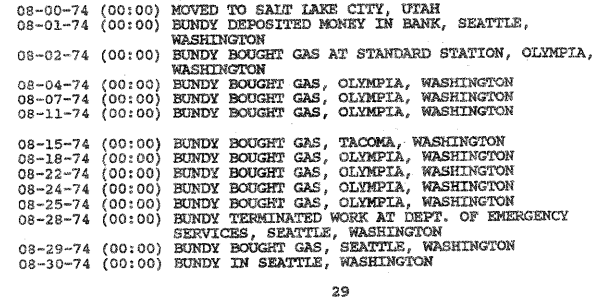

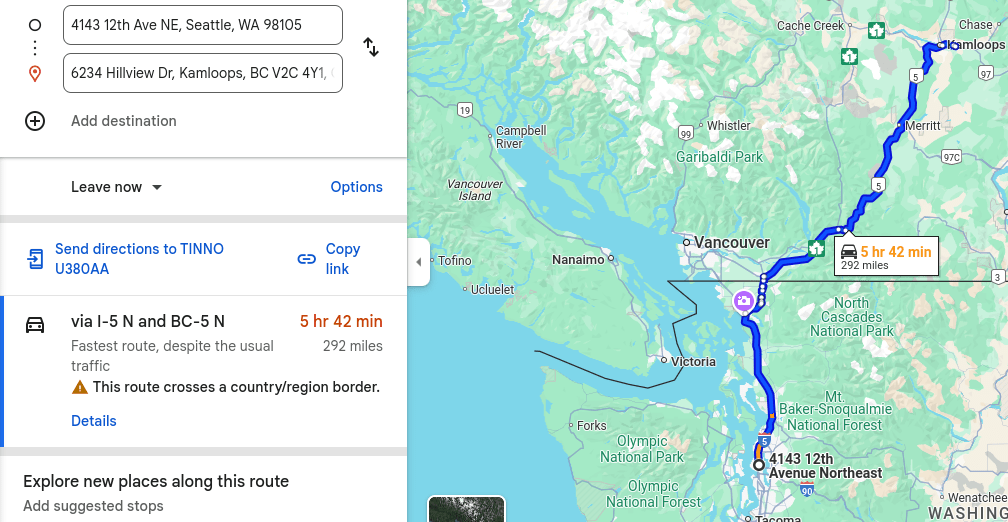

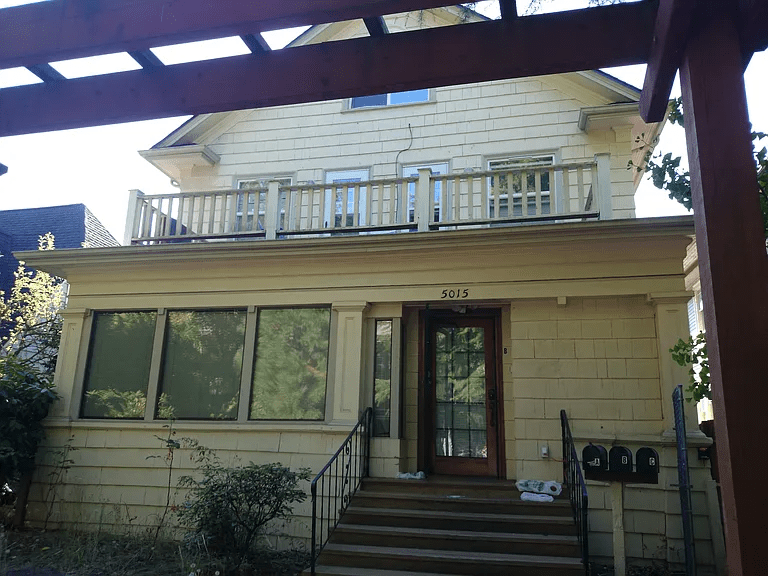

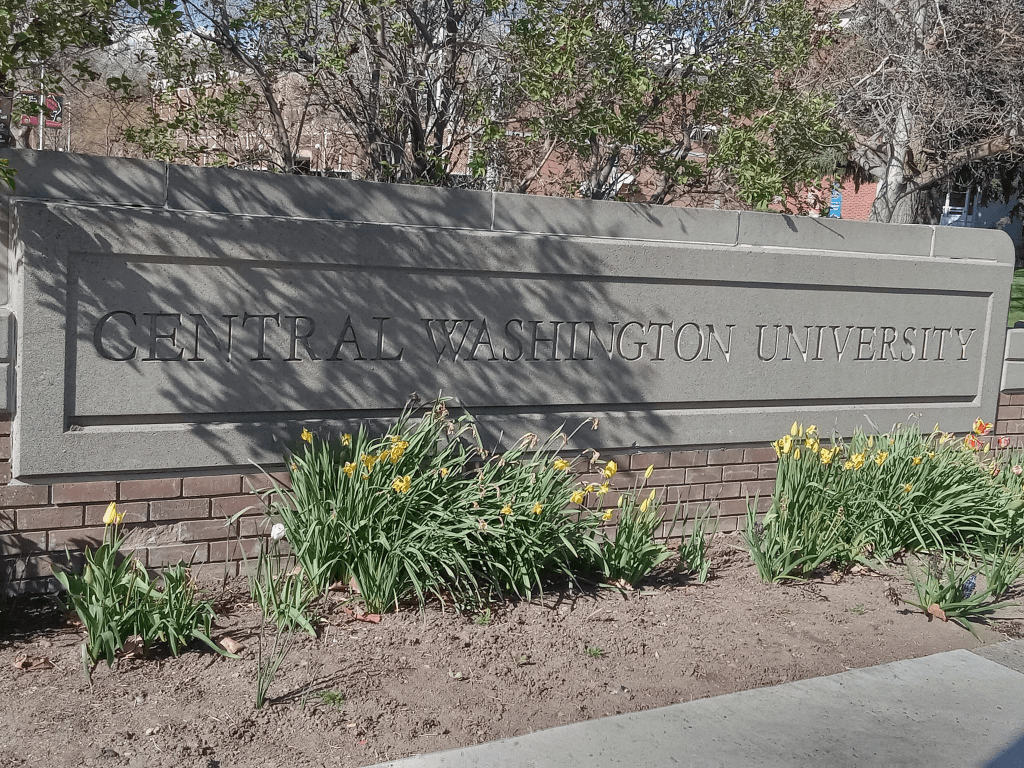

Ted Bundy: In November 1973 when Pam Darlington was killed Theodore Robert Bundy was living in Ernst and Frieda Roger’s rooming house on 12th Avenue NE in Seattle and was in a long-term relationship with Elizabeth Kloepfer. At the time he was in between jobs, and in September he had been the Assistant to the Washington State Republican Chairperson and remained unemployed until May 3 of the following year when he started a position with the Department of Emergency Services in Olympia (he was only there until August 28, most likely because he left for law school in SLC a few days later). At the time he was attending the University of Puget Sounds law school, and according to the ‘TB FBI Multiagency Report 1992′ on November 7 he visited the unemployment office in Seattle.

In her 1981 book ‘The Phantom Prince’ Liz Kloepfer wrote that Vancouver was a ‘favorite playground’ for her one-time beau, and when the two went there in October 1969 he ‘showed her all of his favorite places,’ specifically the saloon ‘Oil Can Harry’s,’ and after spending the night at the former ‘Devonshire Hotel’ they walked through Chinatown as well as a German neighborhood before returning home to Seattle. According to retired RCMP Inspector Bruce Terkelsen, ‘one of the significant pieces of evidence with Darlington was the bite marks on her breasts and other parts of the body.’ As we know, Bundy was known to bite some of his victims, and Terkelsensaid ‘it was a loose piece of evidence at the time. But when we were well into the Highway Murders, the name Ted Bundy came up. It became clear that he was in the habit of crossing the border and coming to Vancouver on numerous occasions.’ He also said that the killer had ‘long ago’ been a suspect in the murders but ‘it became clear that he was in the habit of crossing the border and coming to Vancouver on numerous occasions.’ … ‘At this time Bundy was not a hot suspect, but it was troublesome to us. We spent considerable time trying to track his movements in Canada.‘ Sergeant Bodnaruk also said that King County police placed Ted at several gas stations in the area, which proved he had traveled through Kamloops ‘either a week to ten days before or after Darlington disappeared.’

Living incredibly close to the Canadian border in Buffalo, I immediately wondered about the logistics of Bundy sneaking in and out of Canada to murder young women: I know how strict and regulated things are today (and that’s not even factoring all of this Trump nonsense into the equation), but how hard was it to leave the US in the early 1970’s and go into British Columbia (and return)? After some simple internet sleuthing (and asking my Dad, who was alive and dating my mother in 1973), in the early 1970’s crossing the US-Canada border in Washington state (particularly on the American side going into Canada) was considered relatively easy and straightforward, and there were few (if any) requirements to get over (my dad said he remembers showing them his Erie County Sheriff’s card). Obviously, security has gotten significantly tighter since the days of Ted Bundy, with the introduction of passports/enhanced drivers licenses/real ID’s, enhanced screenings, and stricter identification requirements.

Clifford Robert Olson Jr.: Another serial killer that was investigated for the murder of Pamela Darlington is Clifford Olson, who operated out of Canada in the early 1980’s and confessed to killing eleven children between the ages of nine and eighteen. He was arrested on August 12, 1981 on suspicion of attempting to kidnap two girls, and was later charged with the murder of Judy Kozma, a fourteen-year-old from New Westminster that he raped then strangled to death. Olson eventually came to an unusual and controversial deal with the RCMP: he agreed to confess to the eleven murders and give investigators the location of his victims that were not yet found, and in return for each one that he confessed to they would put $10,000 into a trust for his (then) wife, Joan Hale (who he was with from 1981 to 1985) and their infant child. As a result, Hale and her child received $100,000, as he gave them the eleventh victim as a ‘freebie.’

In January 1982, Clifford Olson pleaded guilty to eleven counts of murder, and was given as many concurrent life sentences to be served out in the Special Handling Unit of the ‘Regional Reception Centre’ in Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines, Quebec. According to forensic psychiatrist Stanley Semrau, who interviewed the killer at great length in prison, Olsen scored a 38/40 on the Psychopathy Checklist; he died from terminal cancer at the age of seventy-one on September 30, 2011.

Miscellaneous Suspects: Another suspect that was investigated for the murder of Pam Darlington is Jerry Baker, who had a history of sex crimes (including rape) and subsequently spent time in prison. On September 19, 1990 it was reported that he had eight convictions for various sexual assault and weapons offenses, as well as a rape conviction in 1970 (for which he received five years) and two separate convictions in 1990 for assault (which drew suspended sentences). His record also notes that he violated his parole conditions in June 1972.

After he was released, Baker returned to the Williams Lake area around the same time that Colleen MacMillen was killed. In late June 1989 seventeen-year-old Norma Tashoots had been visiting family in 100 Mile House, British Columbia and shared with them her plans of hitchhiking her way back to Vancouver. She was last seen by relatives on June 25, 1989 and her body was found in a wooded area near 100 Mile House on July 10; she had been shot in the head.

In October of 1989 an anonymous resident of 100 Mile House came forward and suggested that Baker be investigated for Tashoots’ murder, and law enforcement quickly learned that he had reported his .44 caliber Ruger handgun as stolen the day after she was last seen alive. On February 1, 2002, he was arrested and charged with the first-degree murder of Norma Tashoots, and later that May police recovered the ‘lost’ handgun from 1989 in a sewage lagoon near Forest Grove: it was in excellent condition and was registered to Jerry Baker. On March 2, 2018, a jury in Williams Lake found him guilty of first-degree murder and he was sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole.

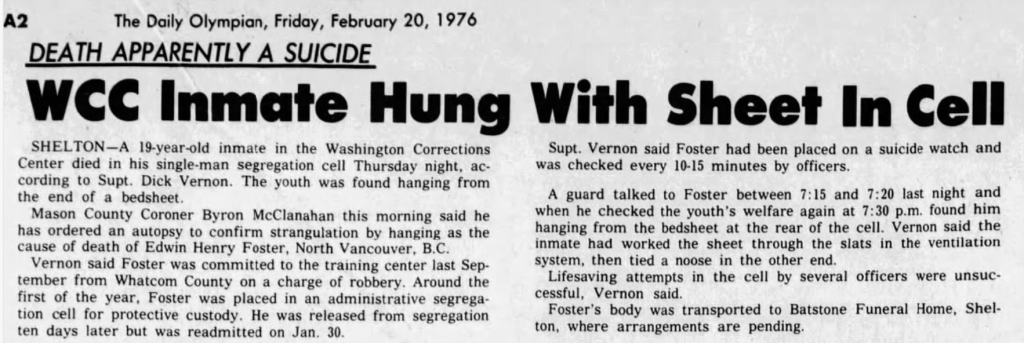

Additionally, In an article published by ‘The Daily News’ on December 19, 2009, it was disclosed that a man named Edwin Henry Foster confessed to detectives that he was responsible for the murder of Pam Darlington while he was serving an eight year prison sentence for a gas station robbery, however this wound up being bogus and he hung himself in a Washington state prison in 1976.

Sharon Darlington is now retired from Canada’s Border Services Agency, and during her long career she worked closely with various law enforcement agencies, and ‘tried hard to find out why Pam’s case remained open, even after they identified Bobby Fowler as her ‘probable murderer.’ I have never understood why DNA would not solve the case. I pursued this for many years, only to hear that the case had many problems with preservation of evidence and I am convinced that evidence was not properly maintained or even kept.’ About her cousin, Sharon said, ‘we were very close. We had plans to move out, get an apartment and start our young lives together. Everyone truly wanted to know the truth about Pam, but my uncle, aunt, father and mother are now all dead.’

Frank Darlington died at the age of seventy-five on May 20, 2002 in Victoria, BC, and Arlene died at the age of 79 on June 17, 2013 in Victoria. Laurel Darlington-Feal still lives in Kamloops with her husband, Gregory. As of March 2025 the RCMP considers Bobby Jack Fowler a ‘strong suspect’ in the murders of Pamela Darlington and Gale Weys despite there being no DNA evidence linking him to their remains, and as a result both homicides are considered unsolved.

Works Cited:

Blackburn, Mark. (September 25, 2012). ‘US serial killer Bobby Jack Fowler linked to 3 Highway of Tears murders.’ Taken April 1, 2025 from aptnnews.ca

Bujold, Dani. ‘Two Cold Cases And A Solved Homicide: Gale Weys, Pamela Darlington and Colleen MacMillen (1973–1974).’ Taken March 20, 2025 from medium.com

Lazarus, Eve. ‘The Pamela Darlington Murder.’ (November 6, 2022). Taken March 20, 2025 from evelazarus.com

LaRosa, Paul. (May 27, 2016). Crime Mystery of missing, murdered women along Highway of Tears.’ Taken April 1, 2025 from cbsnews.com

Martell, Allison. (September 25, 2012). ‘Canadian Mounties solve 1974 murder of 16-year-old girl.’ Retrieved February 17, 2024, from reuters.com

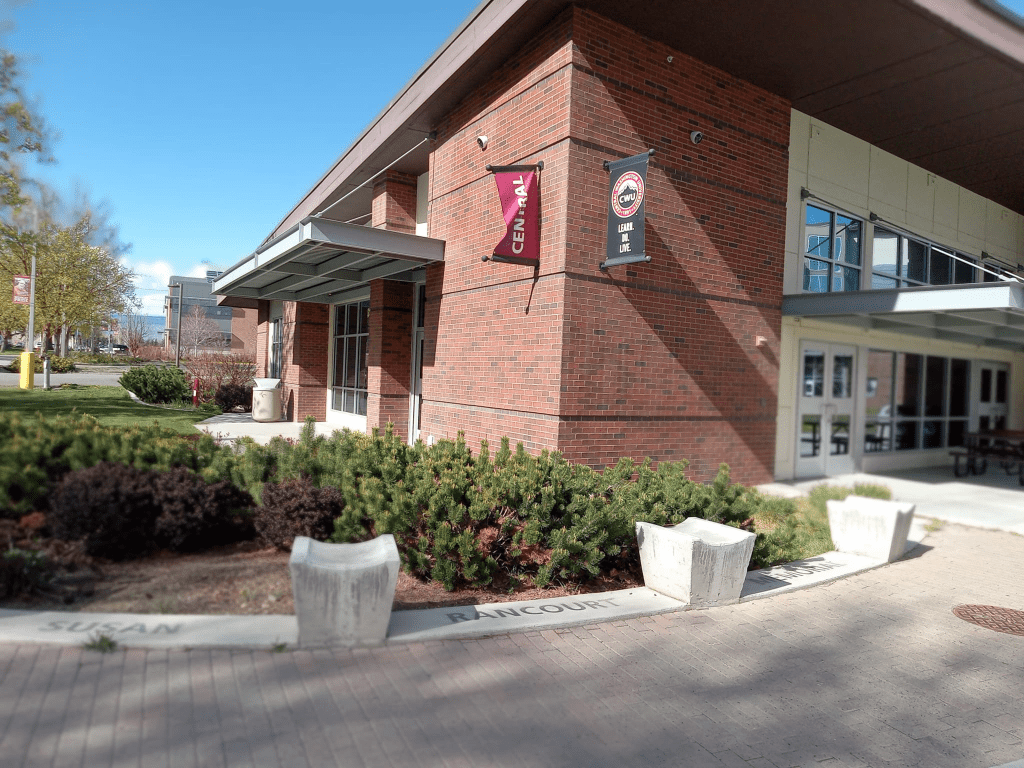

Katherine Merry Devine, Case Files: Part Four.

Katherine Merry Devine, Case Files: Part Three.

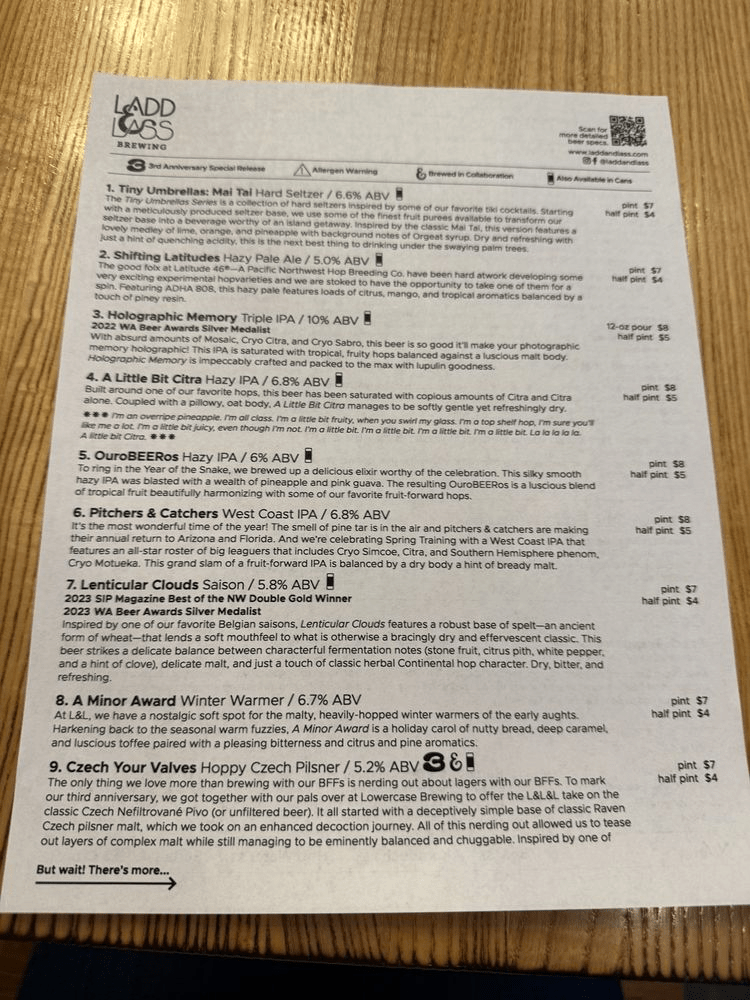

Ladd & Lass, formerly ‘The Sandpiper Tavern.’

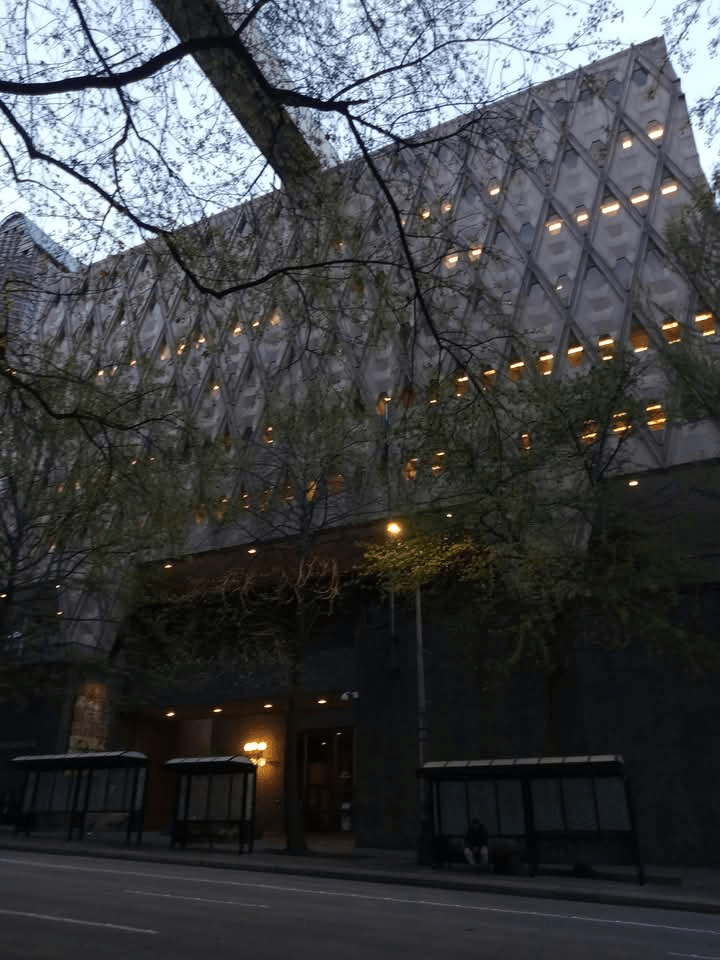

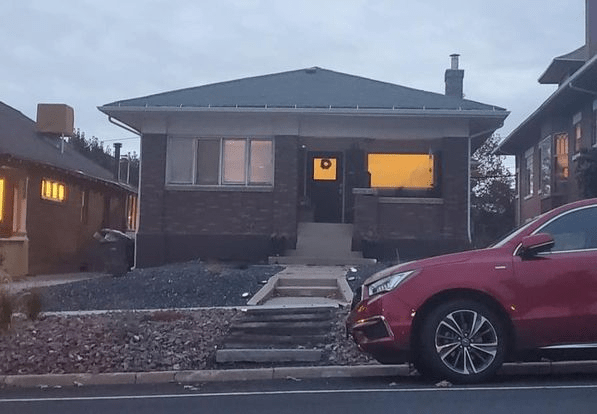

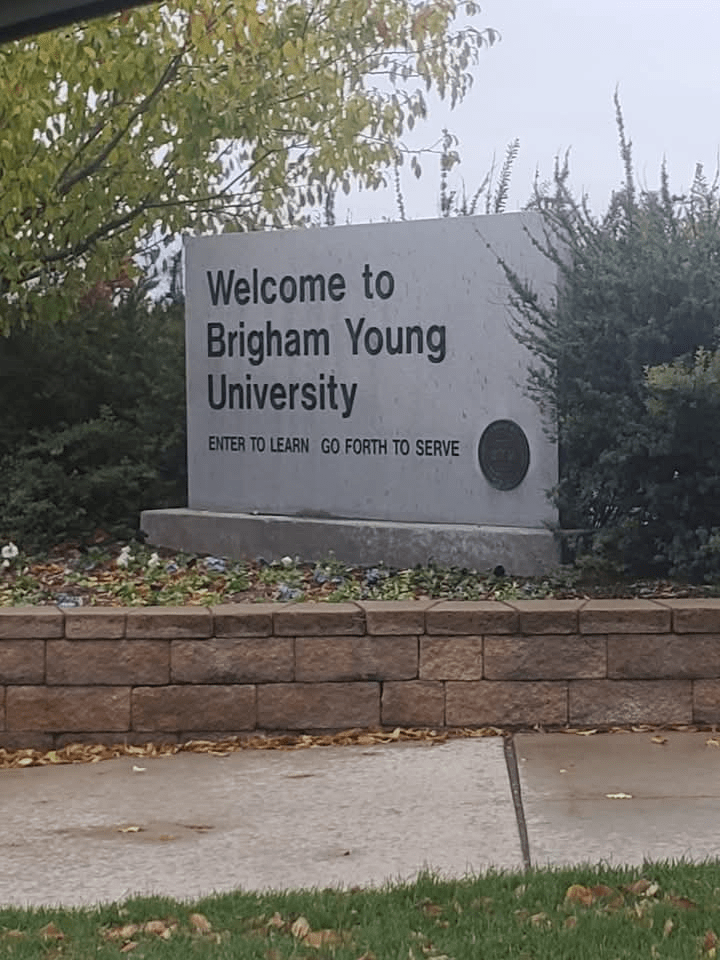

It’s a story most Bundy fans know well: in September 1969 Elizabeth Kloepfer was new in Seattle, and one night along with her friend and fellow Utah transplant Mary Lynn Chino went to a small college bar called The Sandpiper, where she met Ted Bundy. The two went on to have a tumultuous, on again/off again six year relationship, and Ted played a big part in raising Kloepfer’s young daughter, Molly. Over the years The SandPiper Tavern has changed hands (and names) a few times, and most recently has been dubbed ‘Ladd & Lass Brewing.’

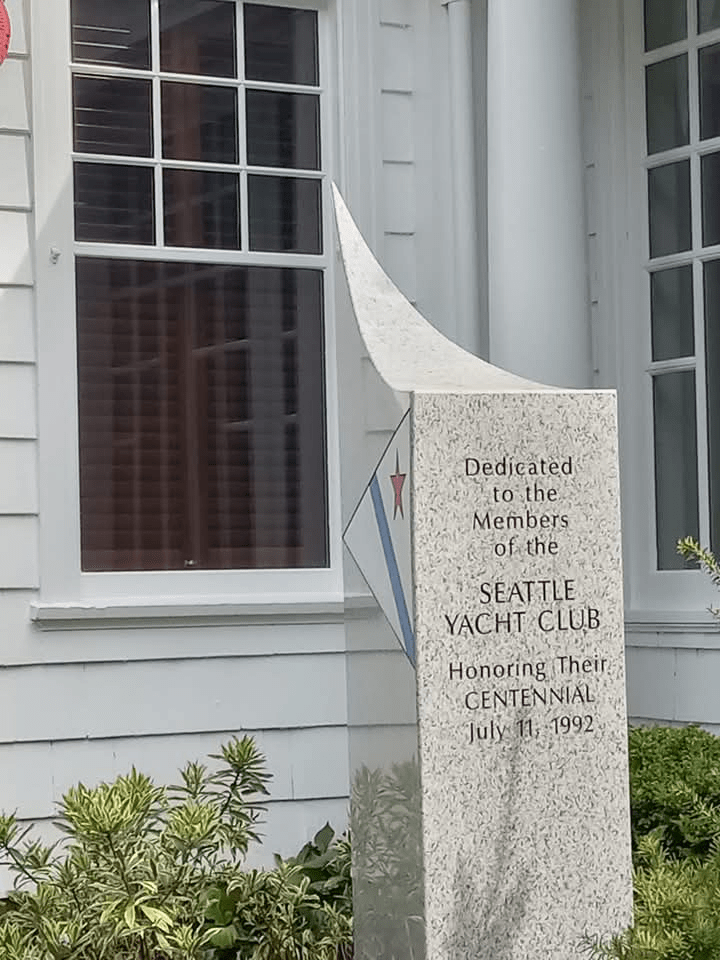

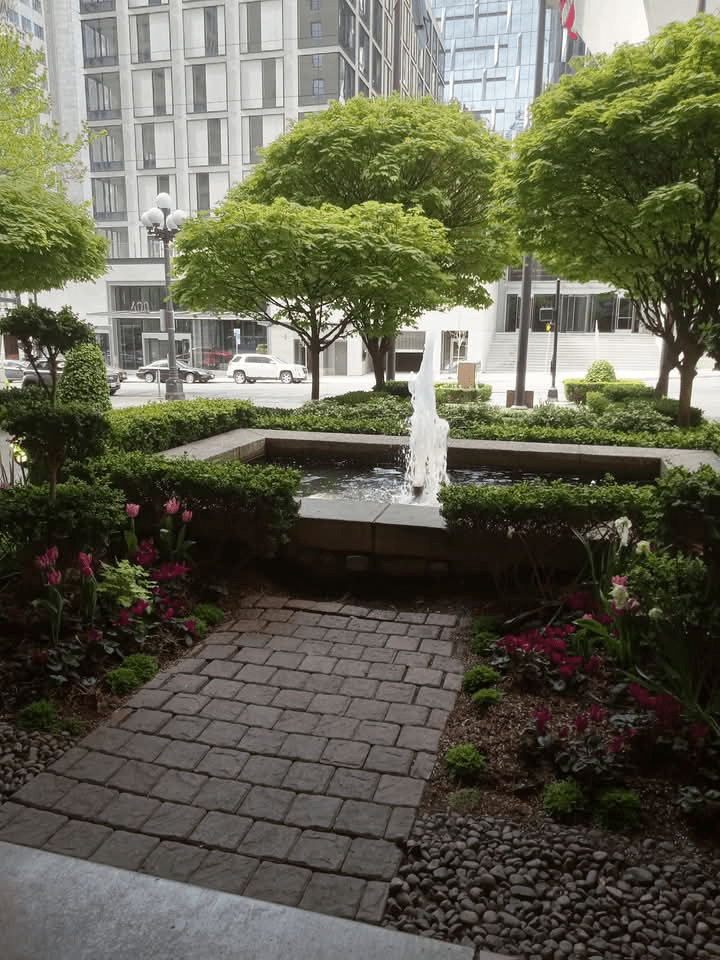

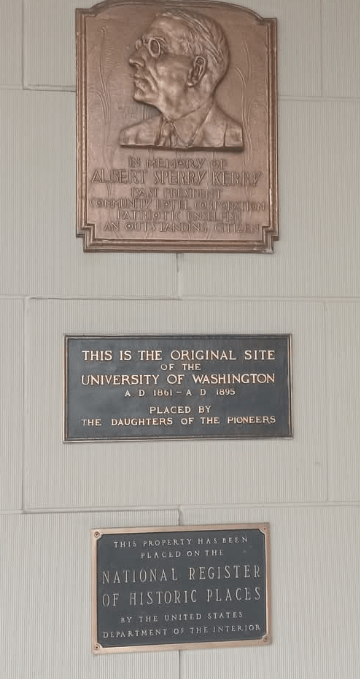

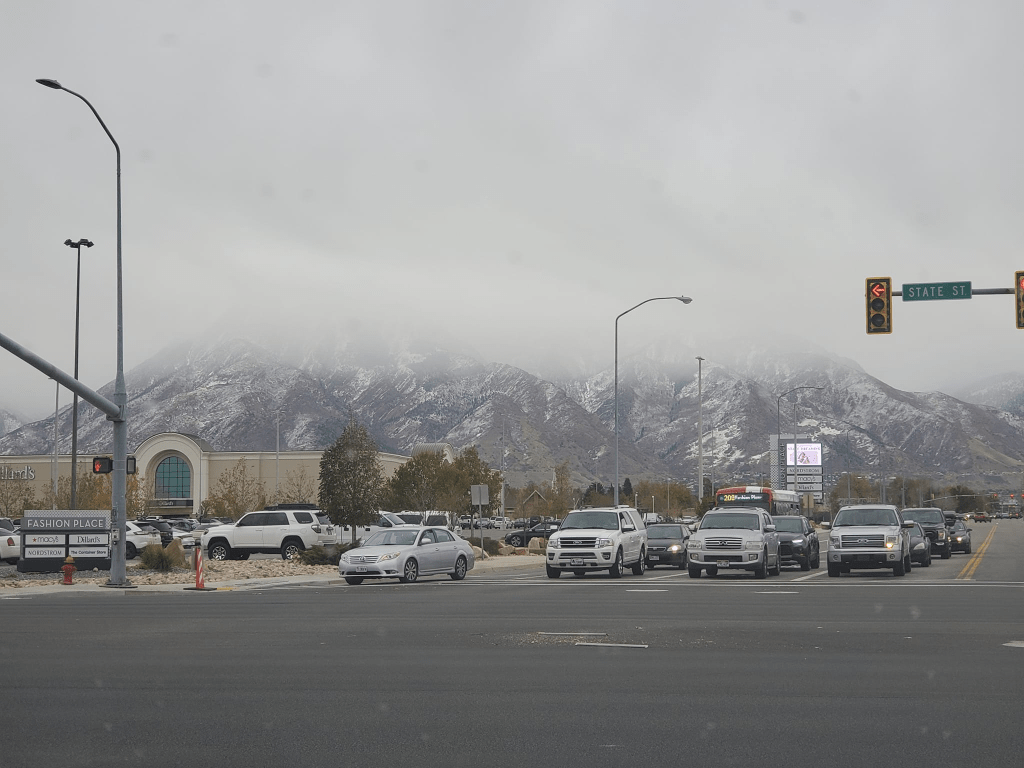

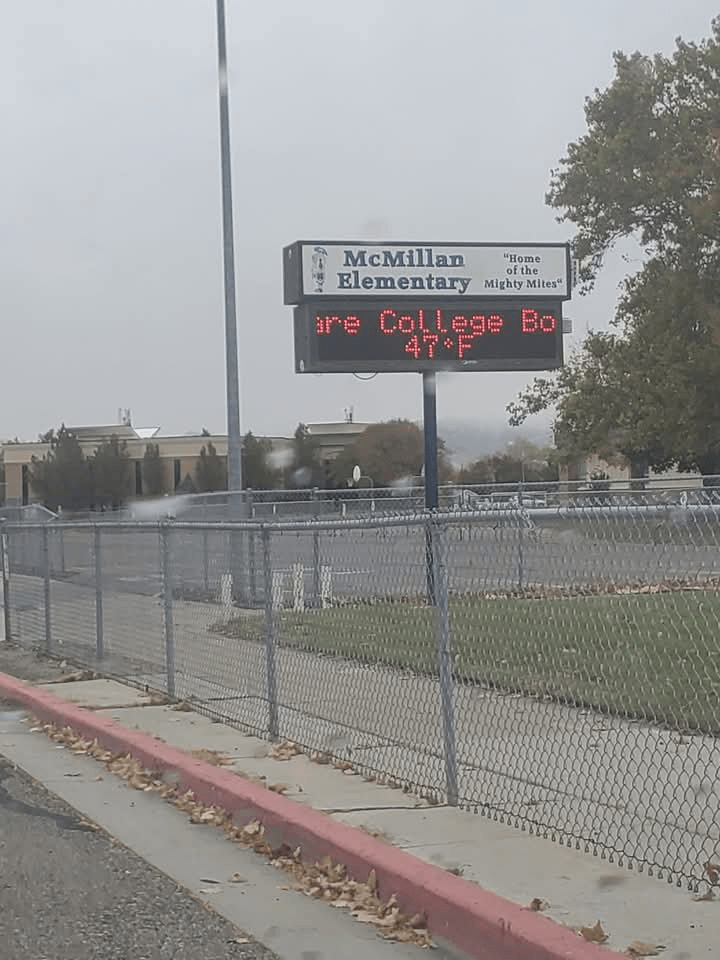

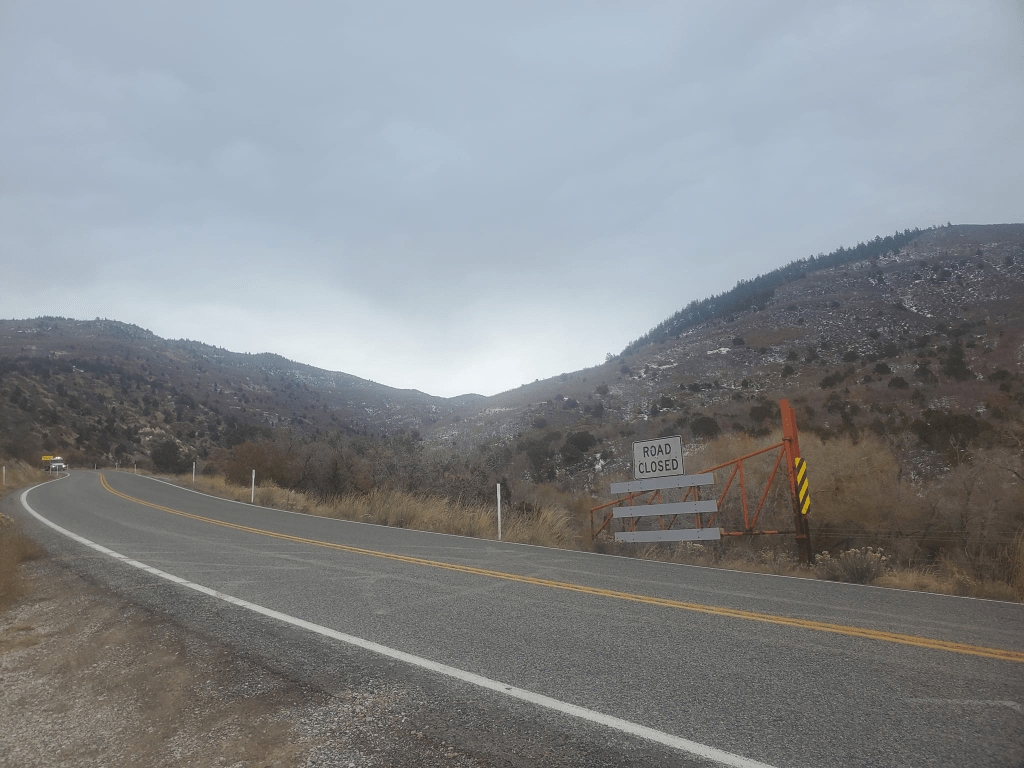

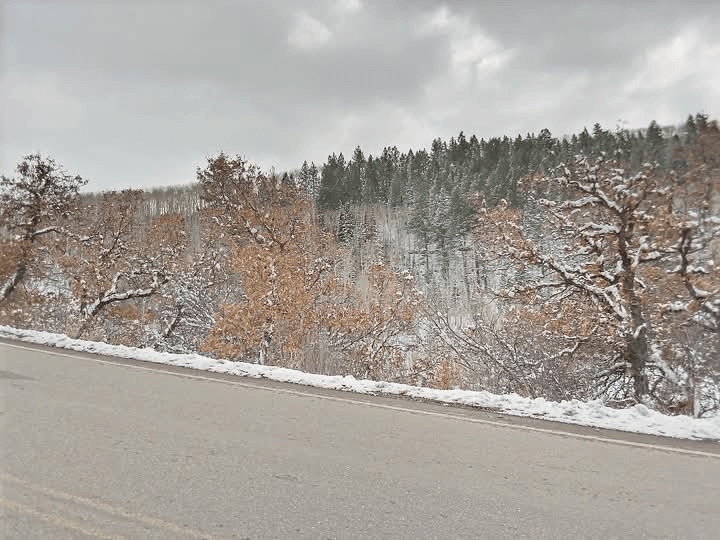

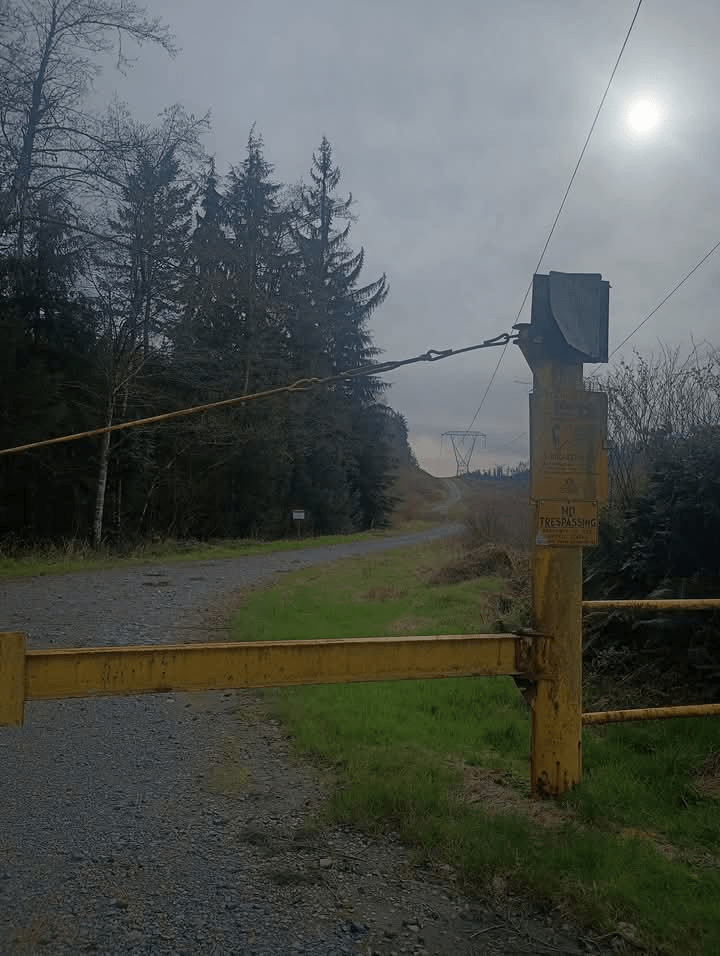

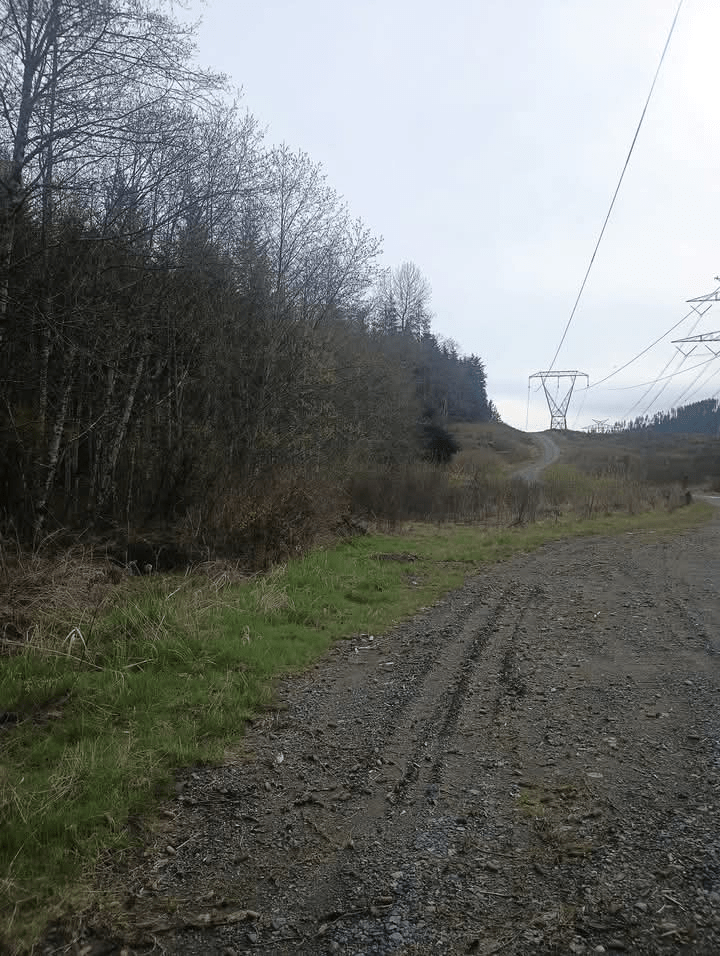

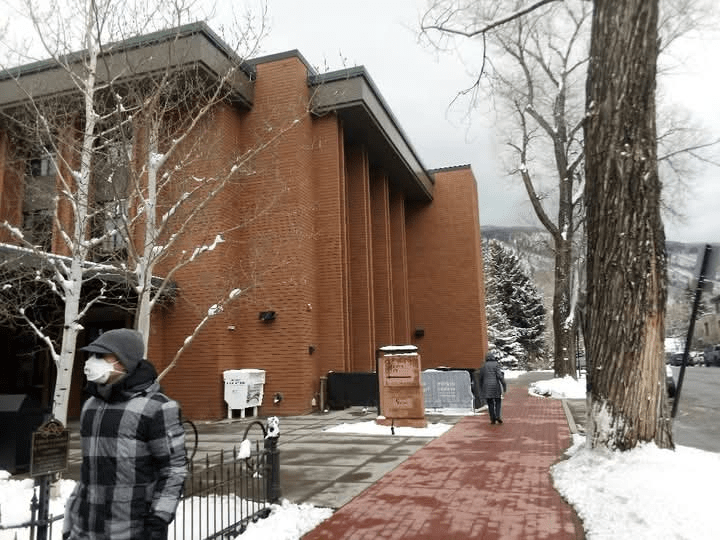

Ted Bundy Crime Scene Locations as they Appear Today, My Personal Pictures.

Up until about five years ago I lived paycheck to paycheck, and after getting two really good jobs I banked quite a bit of money and decided to start traveling. In April 2022 I went to Seattle and since then have been to Florida, Philadelphia, Salt Lake City, Colorado, Cobleskill (in NY, for a suspected Bundy victim) and Portland (on that trip I also went back to Seattle). I’ve been retracing the steps of Ted Bundy and taking pictures along the way.

Bundy entered the dormatory armed only with a piece of firewood, and killed twenty-one-year-old Margaret Bowman and twenty-year-old Lisa Levy; he also brutally harmed Karen Chandler and Kathy Kleiner, but thankfully both women survived. Picture taken in May 2023.

Pamela Lorraine Darlington, .PDF document.

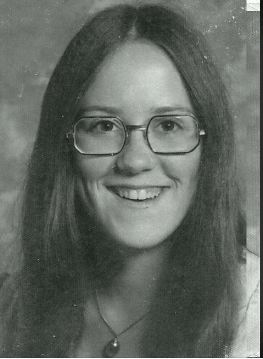

Sherry Rae Deatrick.

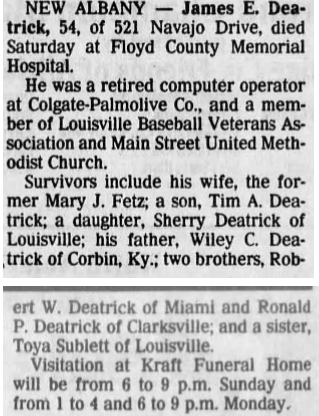

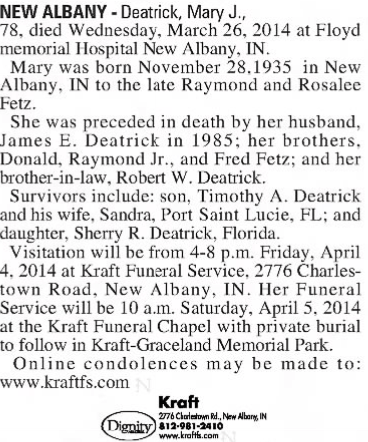

Sherry Rae-Deatrick was born on September 12, 1956 to James and Mary (nee Fetz) Deatrick in New Albany, Indiana. Mr. Deatrick was born on August 20, 1931 and Mary was born on November 28,1935 in New Albany, IN. The couple were wed on March 16, 1956 and had two children together: Sherry and her brother, Timothy. James was employed as a computer operator for the corporate offices of Colgate-Palmolive Corporation and was a member of the Louisville Baseball Veterans Association, and the family was active at the Main Street United Methodist Church.

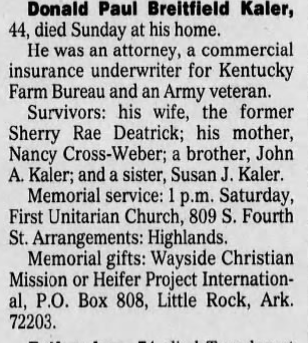

Sherry graduated from New Albany High School in 1976 and went on to earn her BA in Psychology from the University of Louisville, graduating magna cum laude. She briefly lived in NYC, where she was employed with Brooklyn Legal Services and at an insurance defense law firm while she was attending graduate school. At some point she married a man named Donald Paul Breitfield Kaler, and when she returned home to Indiana in 1992 she enrolled in night classes at the Louis D. Brandeis School of Law at the University of Louisville, and worked full time while maintaining top grades. In Deatricks first year of law school she earned the Marilyn Meredith Memorial Award for top female student, and she was a member of the Journal of Family Law.

After graduating from law school in 1997 Deatrick worked at various law firms across the United States, and according to her ‘Linked In’ profile, she has worked as an attorney for herself since 2008, and specializes in both Social Security disability and Department of Veterans Affairs appeals. From November 2004 to 2008 she worked as a Project Manager for Tichenor & Associates, where she was responsible for several government contracts, bankruptcy debtor audits, and state healthcare programs. From 1999 to 2002 she worked as General Counsel under Governor Paul Patton in Frankfort, KY.

On her law practice’s (public) Facebook page, ‘Sherry R. Deatrick, Attorney,’ on February 23, 2012 she announced: ‘I am now admitted to practice in the US District Court, Southern District of Indiana. Looking for office space in my hometown of New Albany.’ And almost ten years later on October 14, 2021 she said; ‘I’m back! I have relocated back home from Florida and I’m re-establishing my solo law practice again. My main focus is on social security disability law and bankruptcy. Serving Kentucky and Southern Indiana.’

Deatrick claims that she had an encounter with prolific serial killer Ted Bundy in the summer of 1974, and although she doesn’t provide an exact date that rough time frame fits perfectly into when he was active. I do want to say that on two separate occasions I tried to reach out to Sherry for clarification on this, but she didn’t see either of my messages. One day during summer school Sherry had gotten into an argument with her fiance and stormed away from him in a fit of anger, and as she was walking she was offered a ride from none other than Ted: “I’d had an argument with my fiancé and as he usually gave me a lift home from summer school, I set off home on foot. Then this cute guy pulled up and asked if I wanted a ride.’ She hesitated briefly, as she wasn’t one to take rides from strangers but after the man reassured her that she was safe, and he ‘was an assistant professor at the local school’ and ‘acting out of anger at my fiancé, I got in.’

Sherry told the man her address, which was roughly three miles away from where he picked her up in New Albany, Indiana, but instead of driving her directly home he stopped at a store to buy some beer: ‘he hadn’t asked my age and I wasn’t going to tell him how young I was. As we drank the beers, he said, ‘Why don’t we go for a ride?’’ She agreed. As the pair crossed the Ohio River and drove into a different state she began to feel nervous, and ‘felt a little worried but things were different in the 70’s. People were a lot more free sexually and I was no exception. It was all quite exciting and I decided to follow his lead though that seems pretty stupid now.’

At the time, Deatrick said that she was titillated at the thought of a romantic encounter with a handsome stranger, and called Bundy ‘handsome and hypnotic,’ which are words that are frequently used to describe him. After cruising around for about thirty minutes or so they arrived in Louisville, Kentucky, and the young man suddenly pulled off the main drag and into a parking lot: ‘it’s clear Bundy knew exactly where he was headed when he’d started driving. He must have scoped it out before picking me up. At the time I thought the location was a bit weird as the new housing estate wasn’t finished but I was quite adventurous.’ ‘Ted’ then led Sherry into a house that was under construction and “I thought it was nice that he was kissing me. I was still mad at my boyfriend and wanted to get back at him so I was up for it. Then all of a sudden, his hands were both going around my throat. I started to say, ‘Wait. Hold on.’

It was at that moment that they heard construction workers calling out nearby: they had returned from a break. About how things played out, Sherry said that ‘he was clearly rattled when he heard the voices and it was like he’d been shaken out of a trance.’ The man immediately took her back to his Beetle, thus ending their brief encounter: ‘I didn’t understand what had gone wrong. Why had he driven us all this way to make out, and then stopped suddenly? I worried I’d done something wrong?’ After driving back to New Albany in complete silence, ‘Ted’ dropped Deatrick off near her parents’ house then drove away into the night. She never saw him again.

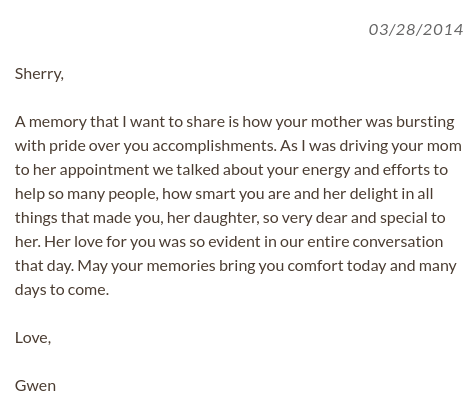

Sherry kept the event to herself, and didn’t tell anyone about what happened to her. It wasn’t until the 1980’s that she read a book about Bundy and strongly felt there was a ‘good chance’ he was the man that she shared a brief romantic entanglement with in the summer of 1974. She speculates that maybe he was in the area looking at law schools to possibly attend: ‘maybe Bundy had gone there to scout it out and happened across me walking home. Later I heard Bundy say there were women in Kentucky who were lucky to be alive. I am certain I was one of those women. I fit the profile for most of his victims, walking alone, upset.’ Only in recent years did Deatrick tell her mother, who has since passed away: ‘she was so shocked but grateful I hadn’t been harmed. I hope young girls who read my story now will be more cautious than I was at that age. I was so naive and trusting and it almost cost me my life.’

In addition to being an attorney Deatrick has worn many hats over the duration of her career: she’s been a playwright, gallery curator, theatre critic, award-winning journalist, and (according to one blogger/artist) ‘a creator of whimsical and mysterious artistic creations.’ According to the website ‘annenberg.usc.edu,’ Sherry was at one time an ‘affiliated freelancer’ with the ‘Louisville Eccentric Observer’ that is based out of Kentucky (she was their theatre critic and won three awards three years in a row for her contributions to the paper). During her time at LEO, she largely focused on the arts and wrote pieces about celebrities like John Waters and local curiosities like Specific Gravity Ensemble (a group known for putting on micro-plays in elevators). Also, according to blogger and artist Jeffrey Scott Holland, Sherry at one time had her own art studio called the ‘Deatrick Gallery,’ which was located in Louisville; her medium included mosaics, crochet amigurumi, and ‘paper-mache miniature heads.’ According to the galleries ‘Geocities’ website, Deatrick’s gallery housed the work of several artists, including Jefferey Holland, Lila Afiouni, and Steve Rigot. She also put on a ‘one-woman performance’ named ‘Heads’ at her gallery in 2004, where she also sold her paper-mache heads that were painted bright colors.

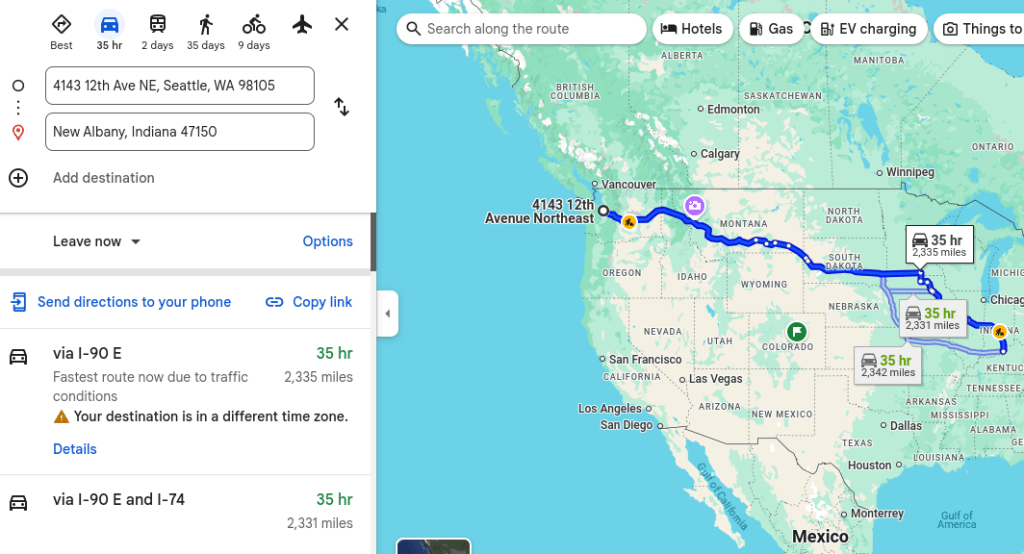

I included Ted’s whereabouts in the summer of 1974 below, and nowhere in it does it say he visited the state of Indiana at any point in time. I understand that not every single one of his movements was recorded, but Indiana is many states away from the Rogers Rooming House in Seattle (where he was living at the time), and was a whopping thirty five hour drive away (and that’s just one way, without stops!). One would think he would have used a credit card to purchase gas at some point in the trip, and therefore would have been listed in the ‘1992 TB Multi agency Team Report.’

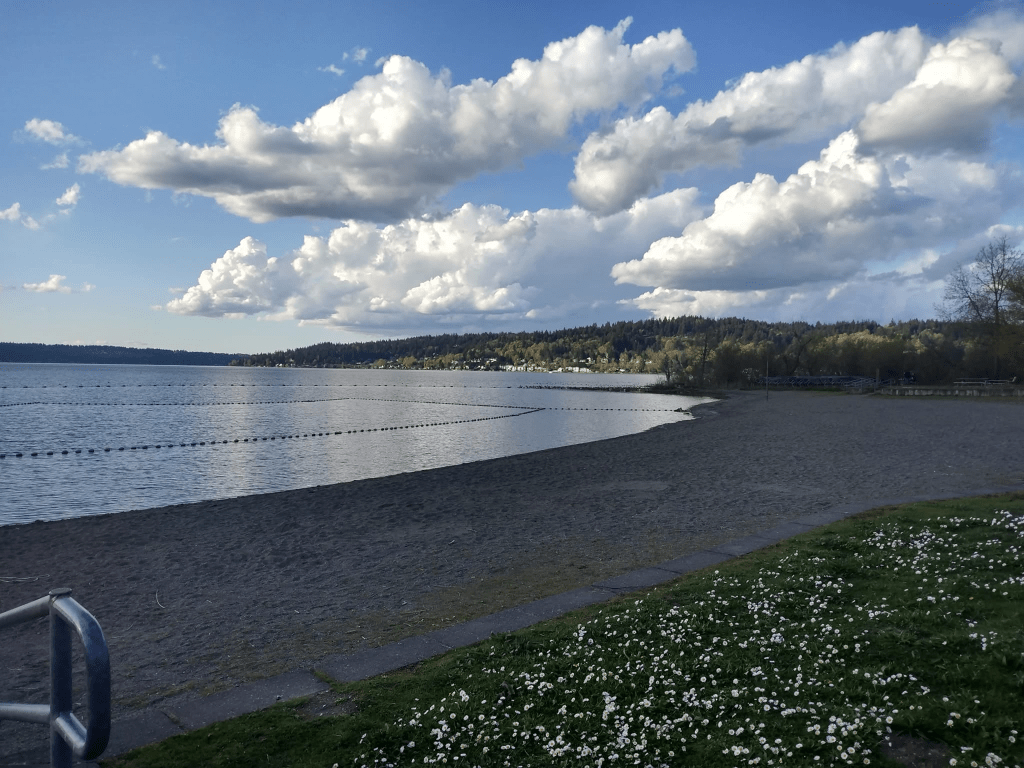

The summer of 1974 was a busy time for Bundy: in the late spring/early summer on May 30/June 1, 1974 he abducted and killed Brenda Carol Ball after she saw a band play at The Flame Tavern in Burien, WA. On June 11, 1974 Ted abducted then killed Georgann Hawkins from outside her sorority house at the University of Washington in Seattle. A little over a month later on July 14 he abducted and killed both Jan Ott and Denise Naslund from Lake Sammamish Park in Issaquah, and in late summer/early fall on September 2, 1974 he abducted and killed the unknown Idaho hitchhiker during his move from Seattle to SLC. At the time Bundy was also in a fairly committed, long term relationship with Elizabeth Kloepfer and was gearing up for his second attempt at law school in Salt Lake City. He also worked from May 3, 1974 to August 28, 1974 at the Department of Emergency Services in Olympia, WA.

Sherry Deatrick is the fourth living victim I’ve written about since I started writing about Ted Bundy (I briefly forgot about Susan Roller/’Sara A. Survivor’). The first was Sotria Kritsonis, who claims she escaped an encounter with Ted in the winter of 1972 after he asked if she wanted a ride while she was waiting at a bus stop on Rainer Street. The two drove around for a while, and after he realized she got her hair cut short he got angry and threw her out of his car. Kritsonis claims she saw him the following year on TV and immediately knew it was him… but it couldn’t have been Ted, because he wasn’t arrested for his crimes against women until August 1975, and he didn’t purchase his tan VW until the spring of 1973. Now, I suppose it’s possible she saw the news story about how he got caught wearing a disguise while infiltrating an event for the Washington state Democratic party, but I highly doubt it.

Rhonda Stapley is one of the more ‘out there’ living Bundy victims, and by this I mean she has been featured in various television specials and mini-series about the serial killer. Stapley was a twenty-one -year-old pharmacy student at the University of Utah when she claims Ted pulled over and asked if she wanted a ride back to her dormitory after a painful dental surgery in the fall of 1974. Like Kritsonis, she was sitting at a bus stop, and not long into the drive he looked at her and said, ‘do you know what? I am going to kill you now.’ He then knocked her unconscious and drove to a secluded canyon just outside of the city, where he beat and sexually assaulted her over and over again for hours before she was finally able to escape by jumping in a nearby stream. She eventually made her way back to the University of Utah, and because she was worried that her mother would pull her from school Rhonda kept the event to herself until 2011,: ‘I imagined people whispering, ‘that’s that girl who was raped.’ I didn’t want attention. I still don’t.’

Susan Lorrayne Roller (who writes under the pseudonym Sara A. Survivor) is an alleged repeat victim and long-time acquaintance of Bundy during the time he was active (and possibly before) in Washington state. She claims that she was friends with Georgann Hawkins as well, and where I couldn’t find any proof of any friendship (as in, pictures of them together) they were Pierce County Daffodil Princesses a year apart (Susan in 1972, Georgann in 1973). Roller claims that she dated Ted briefly before he began to routinely mentally and physically abuse her, and that he also stalked her during their time together at the University of Washington.

Roller has published three books about Bundy: the first is a memoir published in July 2016 and only a limited number of copies were printed (it has since been completely pulled to be ‘rewritten’); her website has disappeared as well because the domain wasn’t properly maintained. The second and third books are more based in facts, and are directly related to the Bundy investigation. In ‘Defense of Denial: Ted Bundy’s Final Prison Interview, 1989’ (published on April 5, 2016), Sarah released some interviews between Ted and Bob Keppell that supposedly provides evidence there were additional victims, and shows proof that police kept information related to the case from the public. Her third book, ‘Reflections on Green River: The Letters of, and Conversations with, Ted Bundy,’ was also published on April 5, 2016 and is ‘a collection of actual documents related to the interviews that took place between WA State authorities in 1984 and 1988 that were released to Roller after years of coming forward.’

James E. Deatrick died at the age of fifty-four on November 24, 1985, and Sherry’s mother Mary died at the age of 78 on March 26, 2014 at Floyd Memorial Hospital in New Albany, IN. Sherry is 67 years old (as of February 2025), and is a widow currently living in Largo, Florida. Her husband Donald Paul Breitfield Kaler died on January 30, 2000 at the age of forty-four, and according to his obituary, he was a US Army Veteran and a licensed attorney; he worked as a commercial insurance underwriter for the Kentucky Farm Bureau. Her brother Timothy A. Deatrick lives in Port Saint Lucie, Florida with his wife, Sandra.

Works Cited:

Deatrick, Sherry. (April 2, 2020). ‘Hypnotised by a Handsome Stranger.’ Taken February 25, 2025 from vtfeatures.co.uk

Deatrick, Sherry. (April 2, 2020). ‘True Life Lucky Escape: Hypnotised by a Handsome Stranger.’ Taken February 24, 2025 from vtfeatures.com

‘Deatrick Law Firm: Sherry R. Deatrick, Attorney at Law.’ Taken February 25, 2025 from piattorneylist.com/online/memberDetail38461.htm

Holland, Jeffrey Scott. ‘Unusual Kentucky: Sherry Deatrick.’ (June 7, 2010). Taken February 25, 2025 from unusualkentucky.blogspot.com

Punteha van Terheyden. (July 27, 2019). ‘Hitching a ride with handsome stranger Ted Bundy nearly cost me my life.’ Taken February 24, 2025 from ‘The Mirror.’

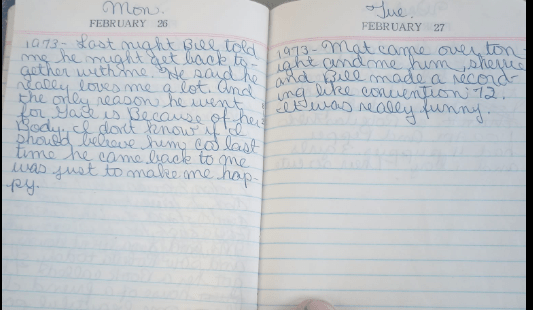

geocities.ws/deatrickgallery/deatrick.html