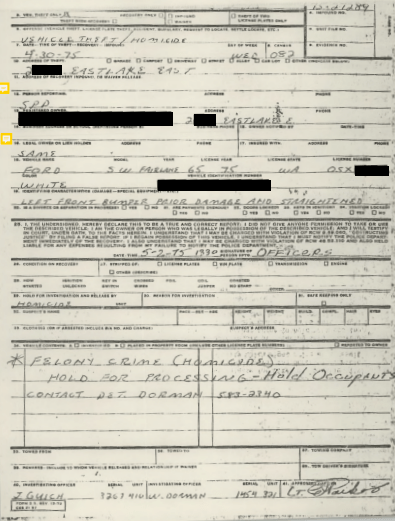

The first installment of case files related to the murder of Vonnie Stuth, courtesy of the King County Sheriff’s Department.

The first installment of case files related to the murder of Vonnie Stuth, courtesy of the King County Sheriff’s Department.

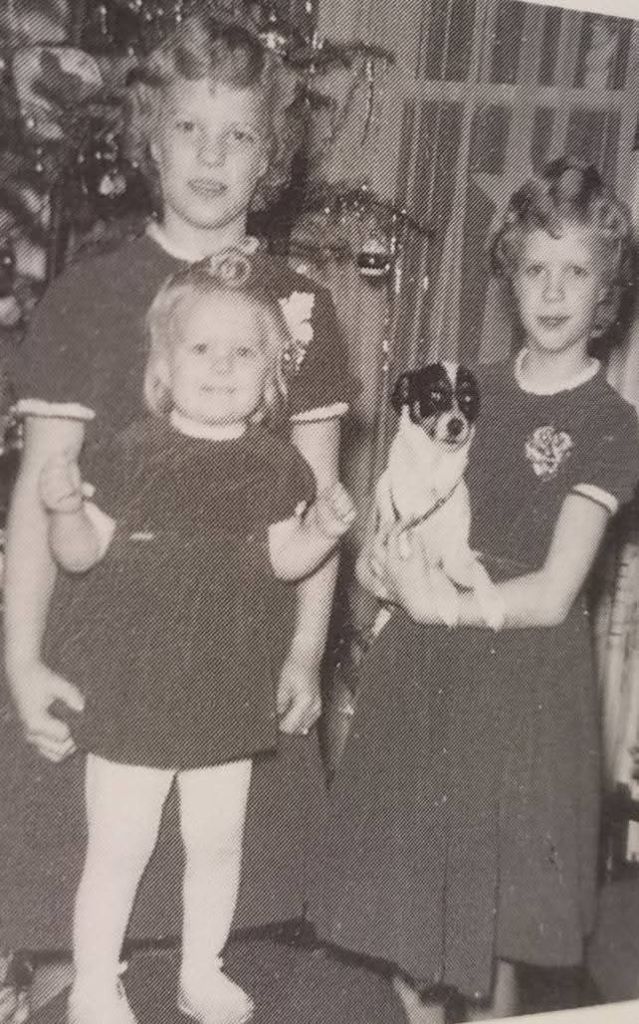

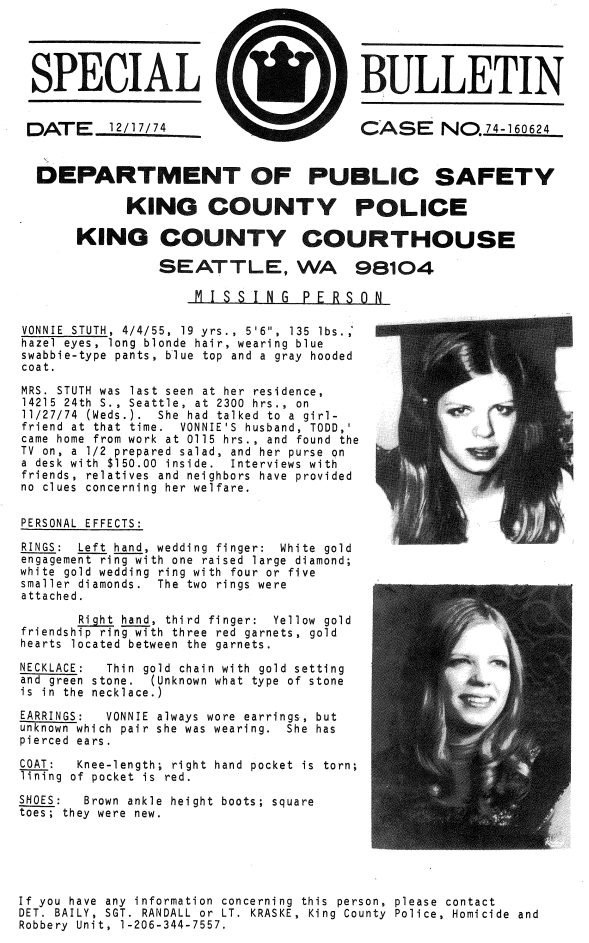

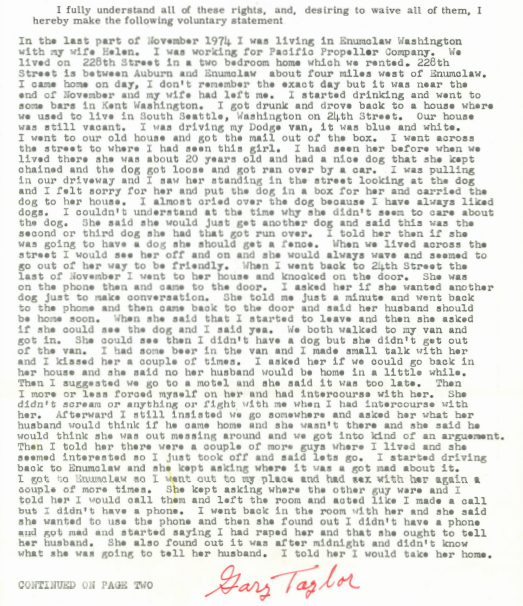

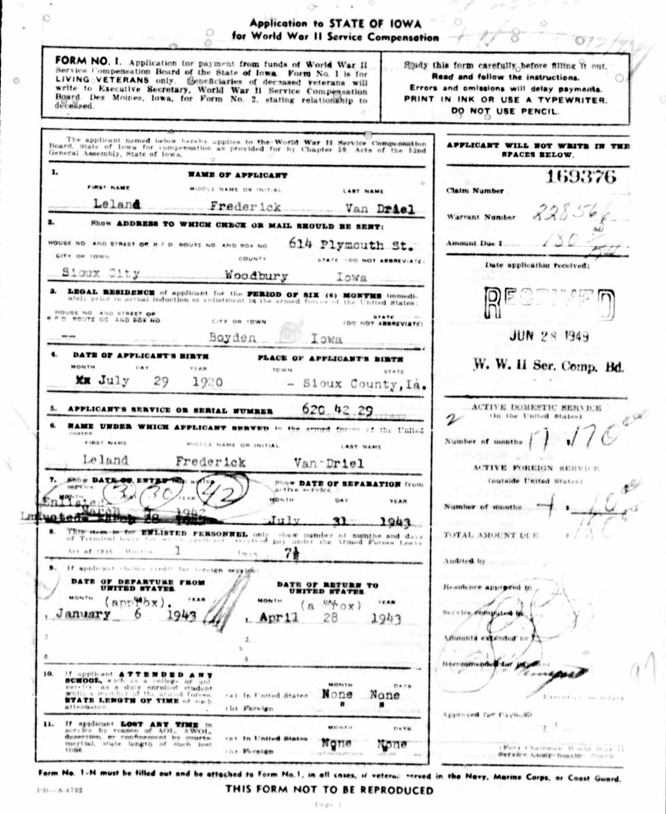

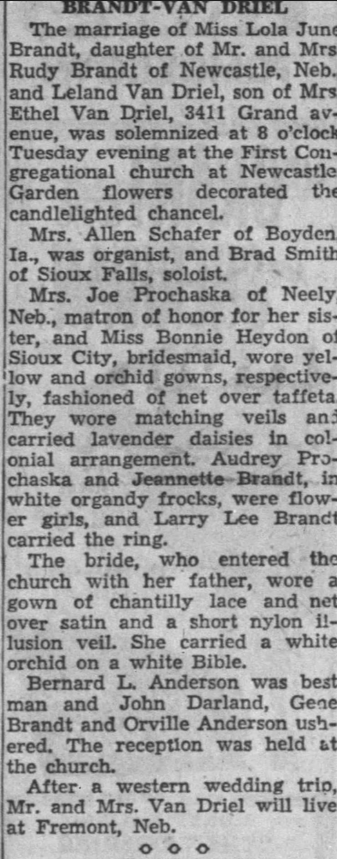

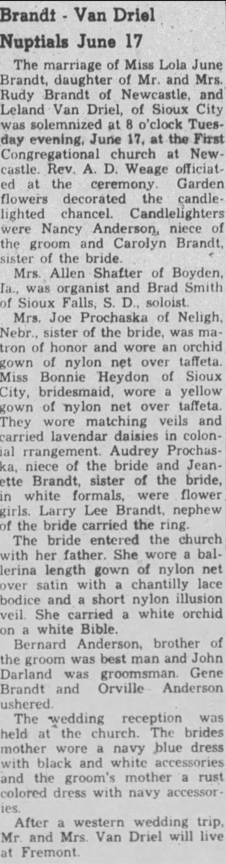

Vonnie Joyce Van Driel* was born on April 4, 1955 in Sioux City, Iowa to Leland and Lola (nee Brandt) Van Driel. Leland Fredrick Van Driel was born on July 29, 1920 in Sioux, Iowa, and Lola June Brandt was born on a farm in Nebraska on June 17, 1932. Leland was married once before Lola to a woman named Betty, and they divorced in May 1950 due to ‘cruel and inhumane treatment.’ The couple were married on June 17, 1952 and had four daughters together: Phyllis, Vonnie, Alicia, and Shirley. They relocated to Seattle when Leland got a job at Boeing, and Mrs. Van Driel was a stay at home wife and mother, and loved caring for her family. She filed for divorce in 1970, which was granted on June 6 and got married for a second time to Kenneth J. Linstad on June 19, 1972. * I have seen the family’s last name as VanDriel as well as Van Driel.

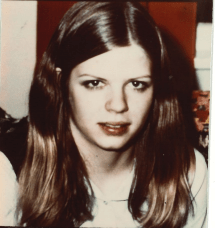

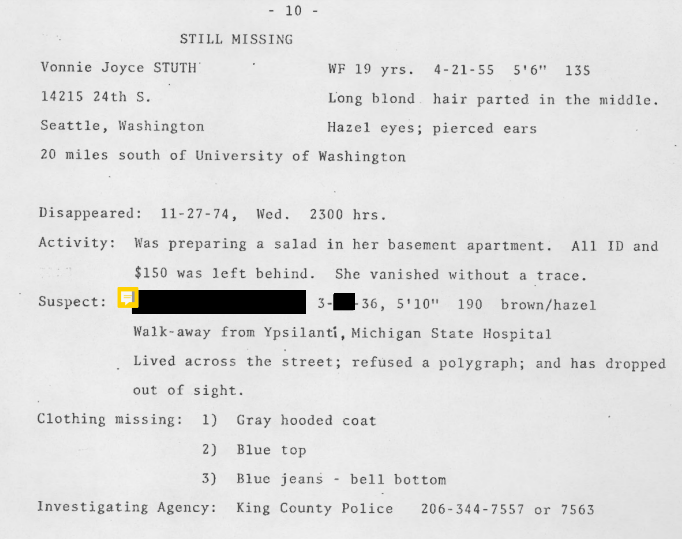

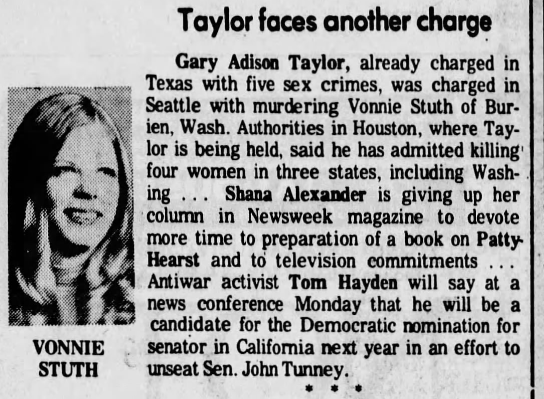

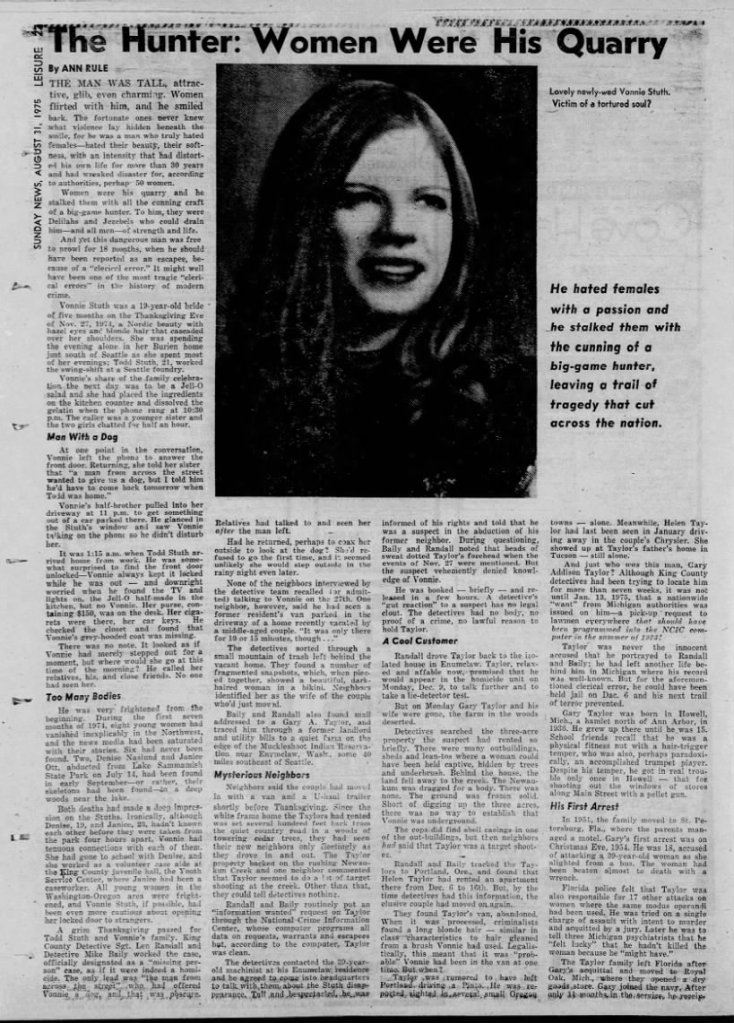

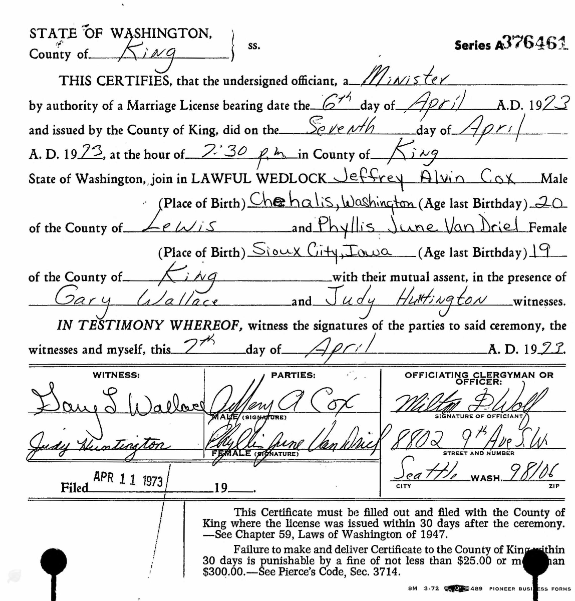

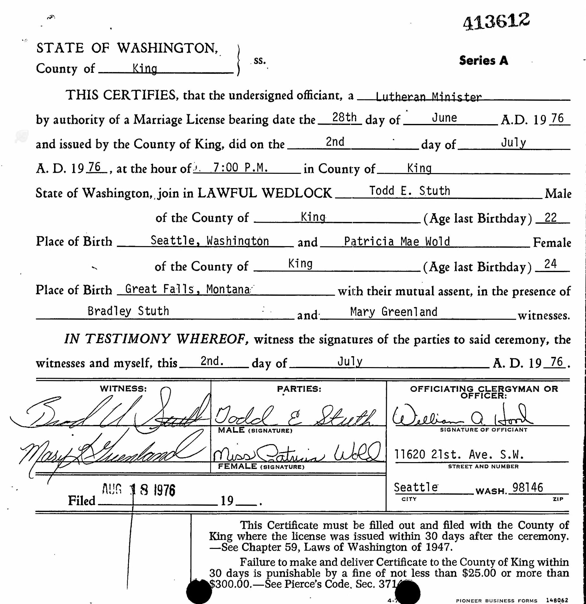

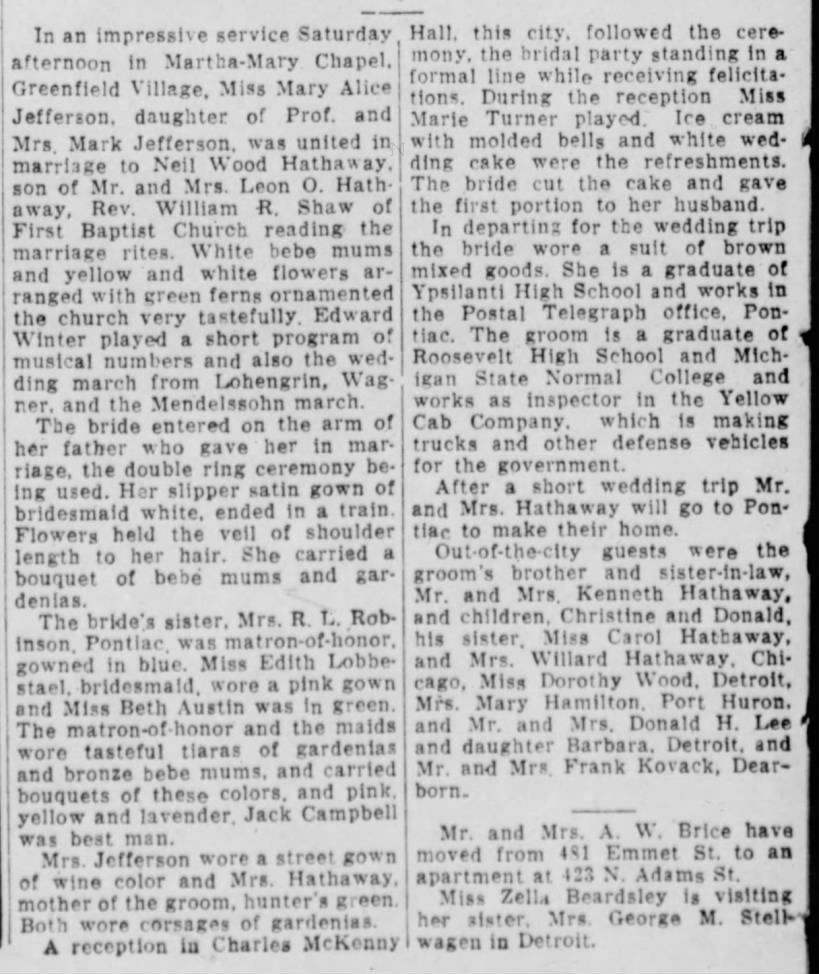

Vonnie graduated from Sealth High School in 1973, and married Todd Stuth on May 4, 1974; according to her marriage certificate, she was a housewife and volunteered at the Youth Service Center in Seattle. The newlyweds moved into a basement apartment located at 14215 24th Street South in Burien, which was roughly twenty miles away from the University of Washington. Todd Elliott Stuth was born on August 10, 1953 in Kent, WA, and graduated from Lincoln High School in 1971. At the time of his wife’s death he was a criminal law major at Highland Community College in Des Moines (which is the same school Brenda Ball attended before she dropped out), and worked the swing shift at Pacific Car & Foundry.

Late in the day on November 27, 1974 Vonnie kissed her husband goodbye in their Burien apartment and sent him off to work: twenty-one year old Todd began his day in the late afternoon and got home after midnight, and she had gotten used to spending her evenings alone. It was the evening before Thanksgiving, and the beautiful young newlywed told her family that her contribution that year was going to be a Jell-O salad, and she had just placed the ingredients on the kitchen counter and dissolved the package of gelatin when her thirteen year old sister Alicia called her at around 10:20/10:25 PM, and the two chatted for roughly a half hour.

Alicia said at one point during their chat, her sister put the phone down to answer a knock at the front door, and when she came back she said that ‘a man from across the street wanted to give us a dog (as they were moving), but I told him he’d have to come back tomorrow when Todd was home.’ Around 11 PM Vonnie’s half-brother stopped over to get something out of one of the family cars parked in the driveway: after looking in the window he saw she was on the phone, and since he knew what he needed and where it was he didn’t bother her.

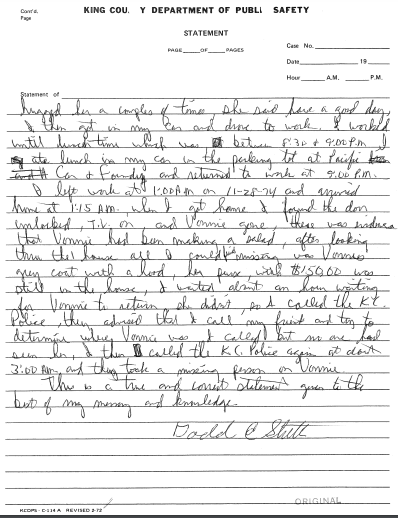

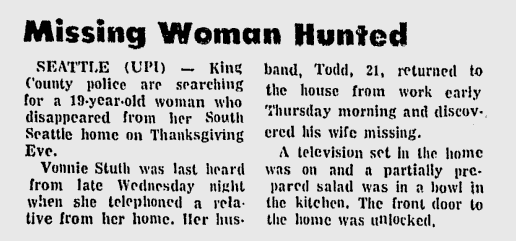

When Todd arrived home around 1:15 AM on November 28, 1974 he came home to an empty house: the front door was unlocked (which was unusual for his wife), the TV was on, and all of the ingredients for the Jello-O salad were left out on the kitchen counter. All of his wife’s belongings were present and accounted for, and her keys, drivers license, cigarettes, and $150 were found in her purse, which was left behind on the counter. Vonnie left no note, and missing from her wardrobe was a blue shirt, a pair of bell-bottoms, and her grey-hooded coat. Todd immediately started calling around to her family and friends, but they hadn’t heard from her; after an hour of waiting he called the King County Sheriff’s Department and tried to report her as missing, but was told by the dispatcher that he needed to wait the standard 48 hours until a missing person’s report could be filed.

The Van Driels/Stuth’s had a grim Thanksgiving with no news about Vonnie, and after the standard forty-eight hours passed Todd was finally able to file a report with the sheriff’s department. King County Detective Sergeant Len Randall and Detective Mike Baily almost immediately designated it as a ‘missing person’ case, and the only real lead they had to work with was ‘the man from across the street that had offered her a dog’ (and even that was vague).

Ted Bundy: In the early part of the investigation Vonnie was thought to be a victim of the mysterious ‘Ted of the Northwest,’ and she was often included in his list of Washington state victims: in the first seven months of 1974, eight young women had vanished in and around the Seattle area, and the news had been filled with their stories. At the time Stuth went missing in November 1974 Ted was living in his first SLC apartment and was a full-time law student at the University of Utah; he was still in a relationship with Elizabeth Kloepfer and the two were trying the long distance thing (despite the fact that he was unfaithful to her on multiple occasions). He was in between jobs at the time, as he left the Department of Emergency Services in Olympia on August 28, 1974 and remained unemployed until June of the following year when he got a position as the night manager of Bailiff Hall at the University of Utah (he was fired the next month for showing up drunk).

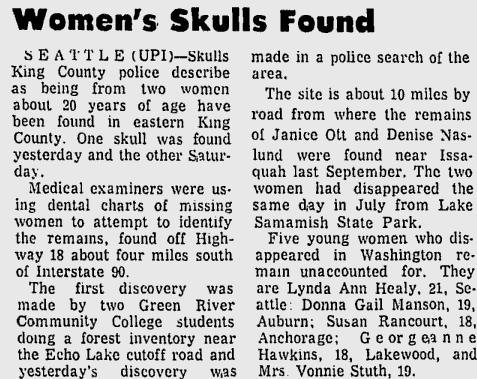

Over time, detectives were unable to establish any connection between Stuth and Bundy, and her case helped to highlight systemic flaws in the missing-persons reporting system at the time. Strangely enough, Vonnie had ties to both of Ted’s victims that were taken from Lake Sammamish State Park on July 14, 1974: Denise Naslund was in the same graduating class as her at Sealth High School, and she worked as a volunteer case aide in the Youth Service Center at the King County Juvenile Hall, where Janice Ott had been a caseworker.

After canvassing the neighborhood, the detectives quickly learned that the man with the dog had already moved Enumclaw, which makes the situation even more unusual since he no longer lived in the area. None of the Stuth’s neighbors recalled talking to Vonnie on the evening of November 27th, but one of them told investigators that he had seen a former resident’s 1972 Dodge van parked in the driveway of the home they had once rented, but ‘it was only there for 10 or 15 minutes.’

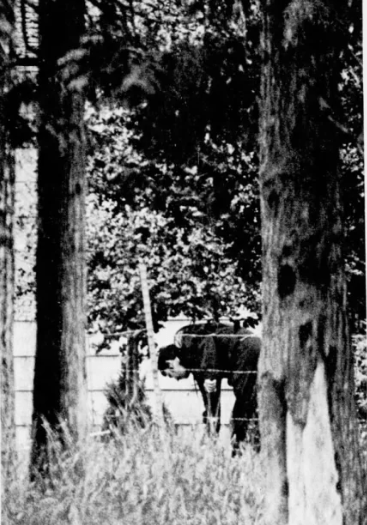

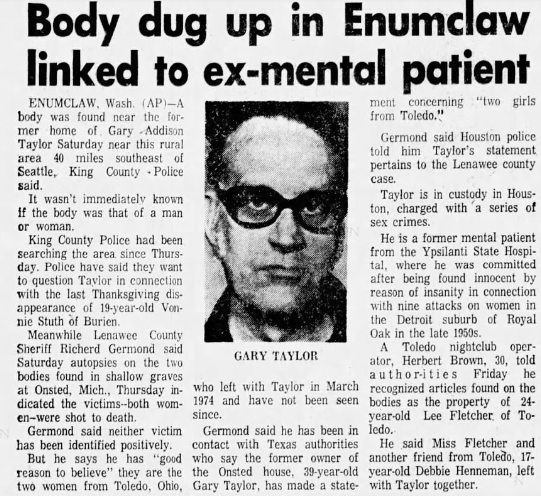

The detectives searched the abandoned home, and went through a ‘small mountain’ of trash that had been left behind by the former tenants and found a large number of torn up pictures; when reassembled one of them was of a beautiful, dark haired woman dressed in a bikini that one of the neighbors identified as Helen, who was half of the couple that had just moved out. The investigating officers also found mail addressed to a man named ‘Gary A. Taylor,’ and they were able to trace him through a former landlord and utility bills to a quiet farm on the edge of the Muckleshoot Indian Reservation, close to Enumclaw.

The Taylors’ new neighbors said the couple had moved into the white frame house with a van and U-Haul trailer shortly before Thanksgiving; the property was located next to the Newaukun Creek and one neighbor commented that Gary seemed to do a lot of target shooting aimed at the water, but other than that they could tell detectives nothing. Officers Randall and Baily put in a few ‘information wanted’ requests on Gary A. Taylor through the National Crime Information Center (whose computer programs all data on requests, warrants and escapees), but he came back clean and with no warrants.

Investigators were brought to a farm in Burien that had been rented by the Taylor’s after receiving reports of ‘unusual mounds of dirt’ found on the property, and according to a King County detective, ‘the story that we were probing for grave sites was possibly a misinterpretation by the media. Searching out there was just a long shot, but we had to check it out. The two earth mounds turned out to be a buried garbage pit and a stump.’

After Detectives Baily and Randall tracked them down, the Taylor’s were brought in for questioning, but they refused to answer any questions, and Gary denied ever knowing Vonnie. The officers got him a public defender and he was booked on December 6, 1974 but was released after a few hours, as their ‘gut feeling’ to a suspect’s guilt had no legal clout, and they had no body, no proof of a crime, and no lawful reason to hold Taylor. He promised King County Sheriff’s that he would come in on Monday, December 9, 1974 for another conversation (and a polygraph), but he never showed up.

After the Taylor’s skipped town detectives searched their residence and the surrounding property: there were many outbuildings, sheds, and lean-to’s where they could have left a body that were all hidden by trees and underbrush. Directly behind the house, the land fell away to the Newaukum Creek, which was immediately dragged for a body but with no luck, and because it was the middle of winter the ground was frozen solid, and short of digging up the entire three acres of property, there was no way to establish that any remains had been buried there; additionally, they found shell casings in one of the buildings next to the main house.

Detectives Randall and Baily tracked the Taylors to Portland and learned that Helen had rented an apartment in her name from December 6 to the 16th, but by the time they learned this, the couple had already left and their van was found abandoned. When the vehicle was processed for evidence, forensic experts found a long blonde hair much like Vonnie Stuth’s, which meant it was ‘probable’ she had been in the vehicle at one point in time… but when? It was rumored that Gary Taylor was to have left Portland driving a Ford Pinto, and he was also sighted in several small Oregon towns (alone).

Gary Addison Taylor was born in Howell, Michigan in March 1936, and childhood friends recall that he was a physical fitness enthusiast that had a hair-trigger temper, but was also an accomplished trumpet player. Despite his outbursts, he had no real juvenile criminal record aside from one incident in Howell when he shot out of the windows of stores along Main Street with a pellet gun. In 1951 when Gary was fifteen the family moved to St. Petersburg, where his parents managed a motel.

While in Florida, he was responsible for ‘the bus stop phantom attacks,’ where he bludgeoned about a dozen women at bus stops during the late 1940’s and early 1950’s; his standard MO involved loitering around bus terminals at night and waiting for someone that was alone to walk by, which was when he pounced and would attack them with a hammer. His first arrest took place at the age of eighteen on Christmas Eve in 1954 after he nearly beat a 39-year-old woman to death with a wrench as she got off of a bus.

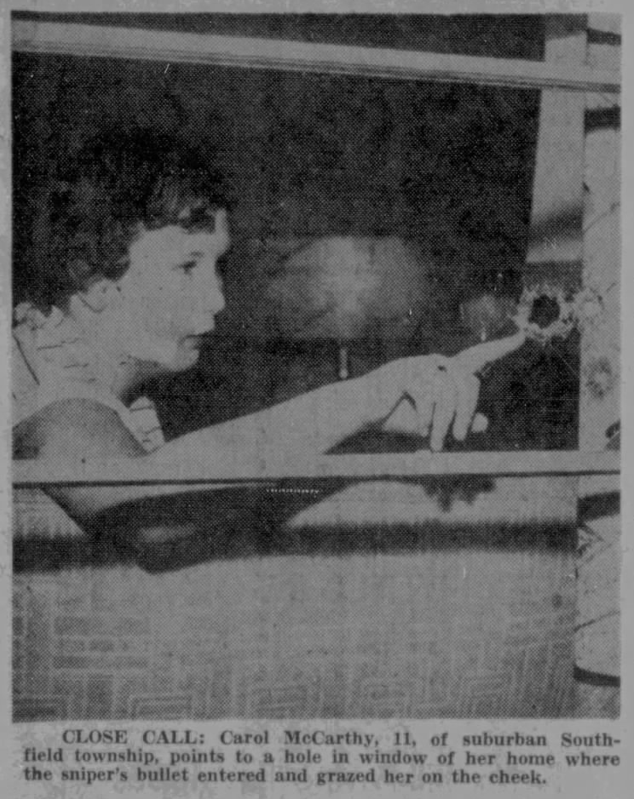

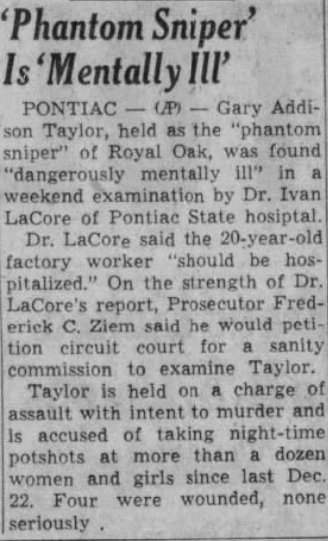

Despite investigators in the Sunshine State speculating that he was responsible for seventeen additional attacks on women where the same MO had been used, he was tried on a single assault charge with intent to kill but was acquitted by a jury; he later told three Michigan psychiatrists that he ‘felt lucky’ that he didn’t kill the woman, because he ‘might have.’ After their son’s acquittal the Taylors moved to Royal Oak, Michigan in 1951, where they opened a dry goods store and Gary joined the Navy… but it wasn’t long before he fell back into his old habits and began shooting women on the streets after dark. He was dubbed the ‘Royal Oak Sniper’ and shot sixteen women, but thankfully none of his victims were fatally wounded.

Two days before Christmas in 1956, Taylor shot and wounded a teenage girl in a drive-by attack in Royal Oak, and over the next few months he shot at several more females in a similar manner but thankfully missed every target. Several witnesses came forward and told police that the sniper was driving a two-toned black-and-white ’55 Chevrolet, and after they located the vehicle the suspect led them on a high-speed chase that ended in his arrest. Upon searching the car detectives discovered a .22 rifle, and Taylor couldn’t give them any particular explanation for his actions other than he wanted to shoot women and had these urges since he was a child, saying ‘it’s a sex drive compulsion.’

During Taylor’s trial, a psychiatrist testified that he was ‘unreasonably hostile toward women, and this makes it very possible that he might very well kill a person,’ and he was declared insane and was committed to Michigan’s Ionia State Hospital; three years later was transferred to the Lafayette Clinic in Detroit. While out on a work pass to attend a welding class, he talked his way into a woman’s home then raped and robbed her; the following year while out on another furlough he threatened a rooming-house manager and her daughter with an 18-inch butcher knife. He was not held responsible for either incident and was simply sent back to Ionia.

Even though he never stopped his violence against the opposite sex and had a self-proclaimed ‘compulsion to hurt women,’ Taylor was rated by prison staff as a ‘safe bet’ for out-patient treatment ‘as long as he reports in to receive medication.’ In 1970 he was transferred to an outpatient care facility after the director of the clinic determined that Taylor ‘was no longer mentally ill and would be dangerous only if he failed to take his medication,’ and drank alcohol.

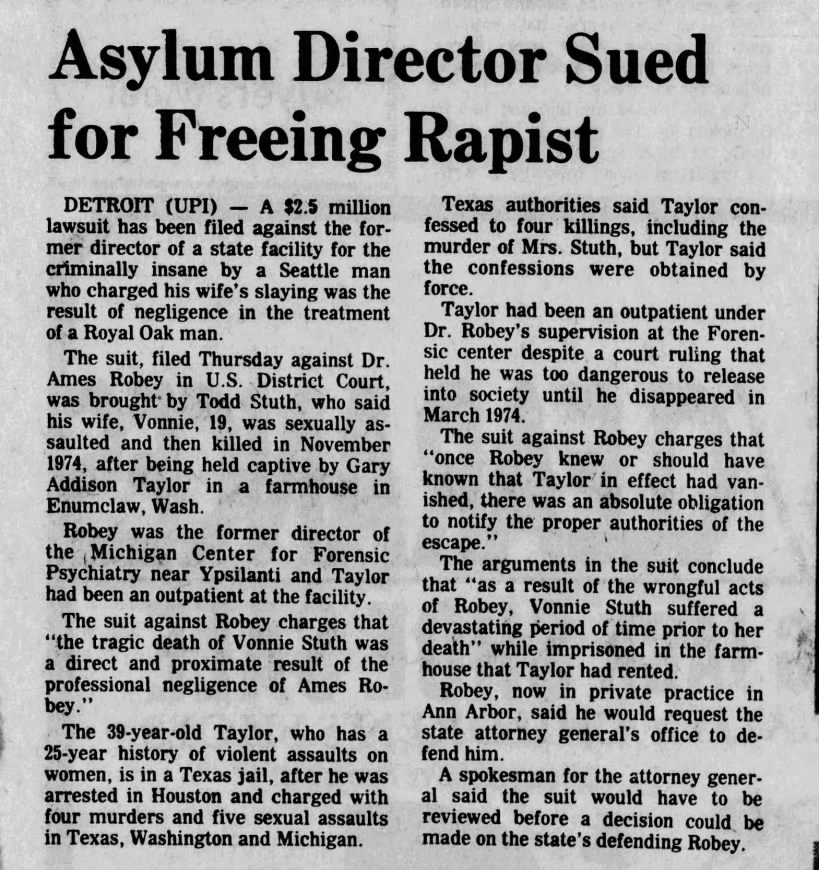

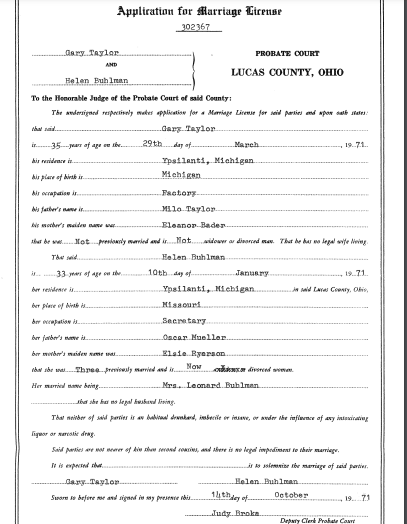

In 1972**, Taylor was released from the Michigan Center for Forensic Psychiatry in Ypsilanti thanks to a highly controversial state law: a person that had been acquitted of a crime by reason of insanity cannot be kept indefinitely in a mental institution and must be periodically declared mentally ill and deemed to be dangerous to himself or the community by a competent medical professional. Before his release, the center’s director Dr. Ames Robey diagnosed him with a character disorder (which is not a treatable mental illness), and felt that he was no longer dangerous as long as he was properly medicated and didn’t drink. Almost immediately after his release, Taylor married a secretary named Helen Buhlman, and the two moved first to Onsted, MI and later to the Seattle suburbs. **There may be some discrepancy as to exactly when he was released, as he was married on March 29, 1971 and another source said it was on November 3, 1973.

The state reported that in the two years after his release Taylor violated the conditions of his parole five times but was never recommitted by the Doctor, and after growing weary of reporting to treatment in late 1973 he completely stopped showing up altogether. When he failed to come in for scheduled check-in’s he wasn’t reported as an escaped mental patient for three months, and it wasn’t submitted into the national law enforcement communication system in Washington DC until January 13,1975. Plus, to make matters worse, when Michigan LE realized their mistake, the urgent bulletin they intended to release on November 6, 1974 never was and it slipped through the cracks.

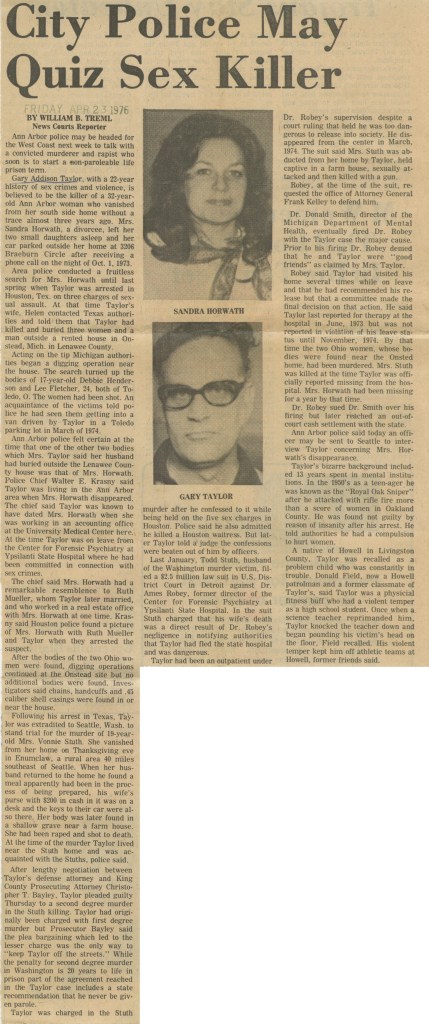

In December 1974 after separating from his wife, Taylor settled down in Houston, and Helen Taylor was last seen in January 1975 driving the couple’s Chrysler when she showed up at her FIL’s home in Tucson by herself. On May 20, 1975 Gary Addison Taylor was arrested in Houston for three counts of aggravated sexual abuse, one count of attempted aggravated rape, the rape of a 16-year-old pregnant girl, and the murder of a 21-year-old go-go dancer.

Discovery: According to an article published in The Times-Union on May 23, 1975, when news of her ex-husband’s arrest reached Helen (by that time she was in San Diego), she called Texas LE and told them that Gary had buried four bodies (three women and one man) underneath their bedroom window in a home they rented for three months in Michigan.

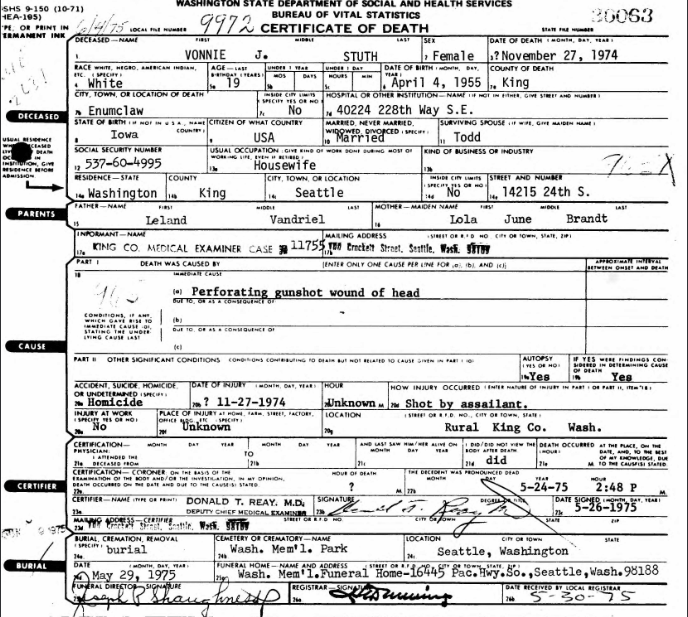

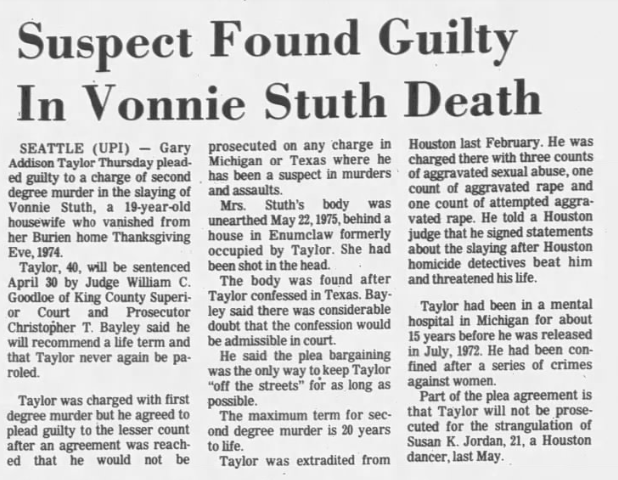

On May 18, 1975 the bodies of Vonnie Stuth and twenty-one year old Houston native Susan Jackson were found by detectives in a shallow grave along Neuwaukum Creek, roughly four to five miles northwest of Enumclaw; Stuth was ID’ed through dental records, and was still wearing the jeans, boots, and gray coat that were missing from her home the evening she disappeared. According to the King County ME, her exact cause of death is listed as a ‘perforating gunshot wound of the head,’ and detectives said she had been shot twice with a 9 mm pistol most likely during a desperate attempt to flee. They also said that due to the advanced level of decomposition it was impossible to tell if she had been sexually assaulted. Detectives said Jackson was last seen alive four days prior to the discovery leaving a Houston bar with Taylor, and her body had been bound with a dog leash and stuffed into a plastic garbage bag.

Tipped off by the Texas detectives, four days after the discovery of Stuth and Jackson investigators in Onsted discovered the remains of twenty-five year old Lee Fletcher and twenty-three year old Deborah Heneman from Toledo, wrapped in plastic bags, buried exactly where Helen said they were. After their discovery the remains were sent to the state police laboratory for analysis and autopsies were performed. Retired Sheriff Richard L. Germond said one of the victims was tied up with a piece of rope and the other had been bound with an electrical cord.

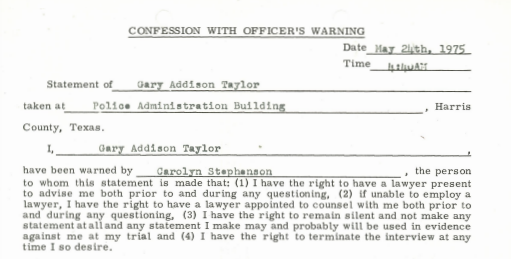

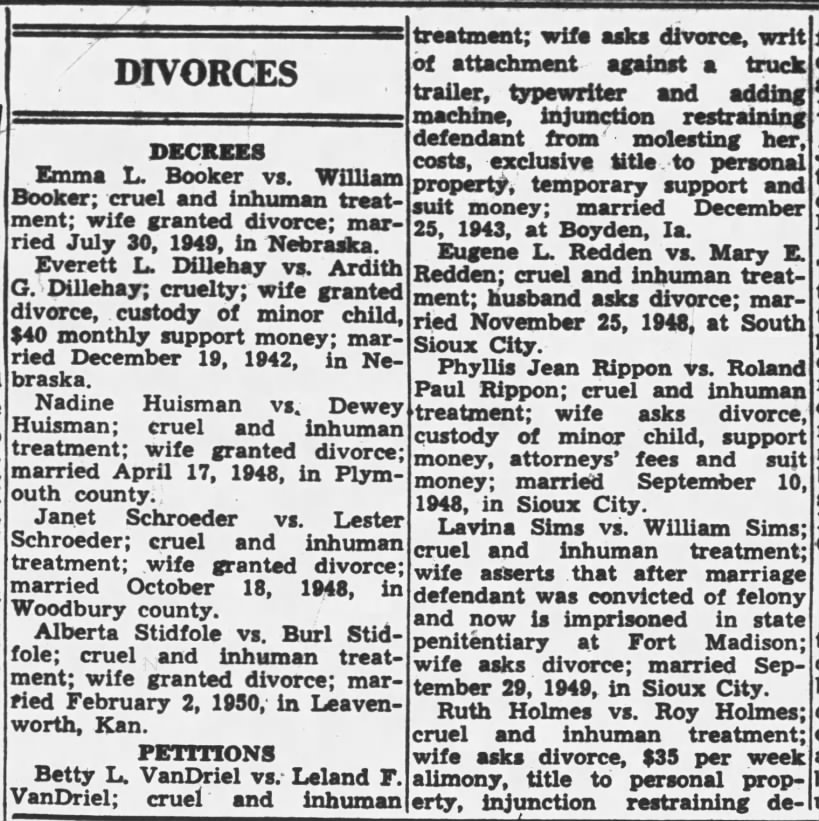

After his apprehension Taylor confessed to four murders (including Vonnie Stuth), however detectives were certain he wouldn’t have told them about any new women that they hadn’t already connected him to, meaning the actual number of his victims is unknown. After he admitted to killing Stuth, Taylor claimed that the detectives in Houston had beaten him into confessing and that there was no attorney present, which made the Texas and Michigan cases problematic. In an article published by The Daily News on August 31, 1975, Taylor was briefly a suspect in the death of Caryn Campbell (who wasn’t physically in Michigan when she disappeared but was from the state) and Julie Cunningham, who were both eventually tied to Ted Bundy. Further investigation cleared him of six additional murders in Washington state.

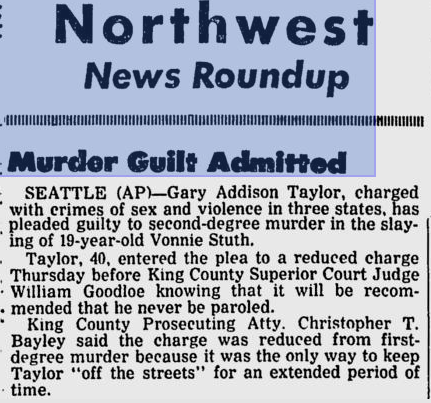

After his confession in Texas Taylor was extradited to Washington, where he was charged with first degree murder for the murder of Vonnie Stuth. On April 30, 1978 he pled guilty to second degree murder after an agreement was reached that both Texas and Michigan would not prosecute him for his crimes and he was sentenced to a ninety-year ‘minimum’ prison term by the Washington state parole board. Years after the conviction one of Vonnie’s sisters provided a victim impact statement to the Indeterminate Sentence Review Board, and Taylor’s parole was denied; his next parole date was set in 2035 when he will be 100 years old.

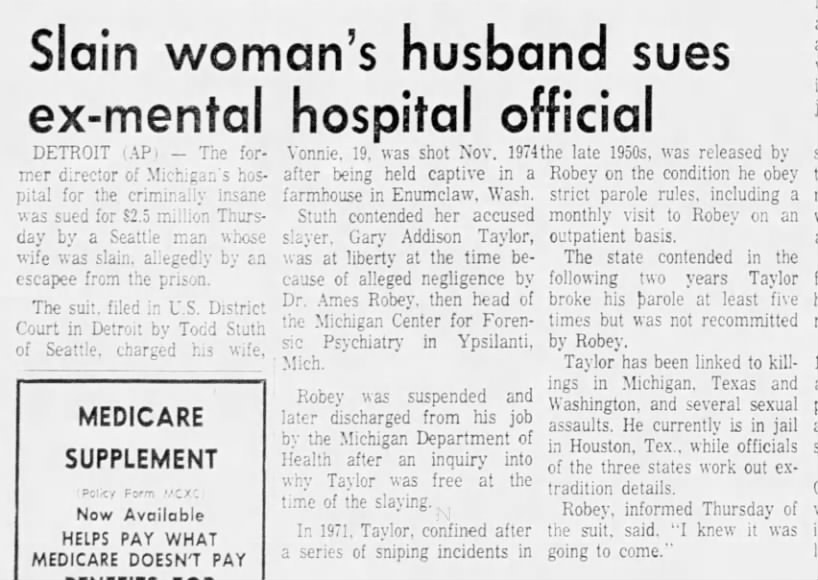

Todd Stuth: According to an article published in The Tri-City Herald on January 23, 1976, Vonnie’s widower Todd sued Gary Taylor’s former Psychiatrist Dr. Ames Robey for $2.5 million, as he was technically the one responsible for Taylor and he escaped under his watch. The former director of Michigan’s Center for Forensic Psychiatry, after the murders came to light Dr. Robey was suspended from his position and was eventually fired by the Michigan Department of Health after an inquiry into why his patient was free at the time of Stuth’s murder. In regard to the court case, Dr. Robey said in an interview: ‘I knew it was going to come.’

VSS/Victim Support Services: Lola ran a day care center out of her home and lived two blocks away from a woman named Linda Barker-Lowrance, and the two met when Linda needed someone to watch her kids when she went to PTA meetings. While waiting for answers as to what had happened to Vonnie, one evening when Linda arrived to pick up her children she said, ‘I am sorry my house is a mess but my daughter is missing.’ … ‘I wonder what the other mothers are doing?’

Despite over a fifteen year age gap between the two (and the fact that they hadn’t known each other for very long), Barker-Lowrance immediately responded, ‘let’s find out.’ The two women reached out to a Seattle-based newspaper reporter, who was able to give them phone numbers and addresses of several other families that had missing or murdered daughters and on February 25, 1975 thirteen families gathered in the social hall of a Catholic church in White Center. The group, officially dubbed ‘the Families and Friends of Violent Crime Victims***’ became one of the first victim advocacy groups in the US. *** It is now simply VSS.

Also a member of the group was Dr. Donald Blackburn, father of Bundy’s Lake Sammamish victim, Janice Ott. In a letter he wrote to President Ford about his daughter, Dr. Blackburn said that he had previously worked as a supervisor for the Board of Prison Terms and Paroles in Washington state, but ‘because of the relaxed supervision and control policies which were coming into effect, I left that service some sixteen years ago.’ President Ford wrote back saying he expressed concern about his daughter’s death and that he would try his hardest to push for reform.

Mrs. Linstad wrote to Bundy buddy Governor Daniel J. Evans in regards to the rights of a murder suspect, saying they ‘go on and on, that leads me to question the rights of the missing girls. There seems to be none.’ Lola’s baby now operates out of a two-story house on Colby Avenue and is staffed by eight full-time employees (including mental health professionals), and volunteers help to operate the crisis line after hours.

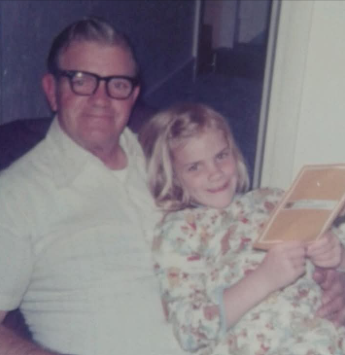

Mr. Van Driel died at the age of sixty-five on July 29, 1985 in Seattle, and Vonnie’s mother Lola died on October 1, 2024 in Sweet Home, Oregon. According to her obituary, at the age of eighteen she enrolled in secretarial college and after she got married and started her family they packed up and relocated to Seattle. She did a lot of fund raising for an organization called ‘The Healing Garden’ at Samaritan Hospital in Lebanon, Oregon and volunteered with a local soup kitchen and FISH food distribution pantry. She also taught Sunday school for many years and was a PTA mother and a Girl Scout Leader.

Over the course of her life Lola had two careers: she worked as a licensed daycare provider for fifteen years and after her daughters grew up she took classes to update her skills and became a family court clerk at the King County courthouse in downtown Seattle. After retiring at the age of sixty-five, she moved to Oregon to be closer to her two daughters. Sadly while in her 80’s Lola lost her ability to walk and was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, Meniere’s disease (hearing loss), and glaucoma (vision loss), but despite these challenges, she was always good natured and lived to be ninety-two.

Phyllis Van Driel-Clem is married and currently resides in Friday Harbor, WA; she retired from Compass Health (which is a community-based, non-profit organization in Washington that provides a wide range of behavioral health related services) in 2017. Vonnie’s sister Shirley Byrd relocated to Oregon and earned her RN from Linn-Benton Community College in June 2002; she is a passionate advocate for those struggling with substance abuse. Vonnie’s youngest sister Alicia lives in Federal Way, WA with her husband, who she has been married to since 1986. Todd Stuth remarried and lives in Kent, WA; he is currently employed as a flight instructor at Crest Airpark.

Gary Taylor is currently 89 years old and is still incarcerated in the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. Michigan investigators strongly suspect that he is also responsible for the disappearance of thirty-three year old Ann Arbor mother of three Sandra Horwath, who vanished without a trace on October 1, 1973. In 2002 detectives went to the prison Taylor was housed at and tried to speak to him about Horwath, but he refused to answer any questions.

Works Cited:

Barber, Mike, ‘Serial killers prey on ‘the less dead.’ (February 19, 2003). The Seattle Post-Intelligencer Reporter.

Gore, Donna. (March 14, 2014). ‘Two Desperate Housewives, First Support Group.’ Taken August 27, 2025 from ‘herewomentalk.com’

Hefley, Diana. (April 18, 2015). ‘For 40 years, group has been there in darkest times for crime victims.’ Taken August 9, 2025 from heraldnet.com

Documents courtesy of the King County Sheriffs Department, this information is worth its weight in gold.

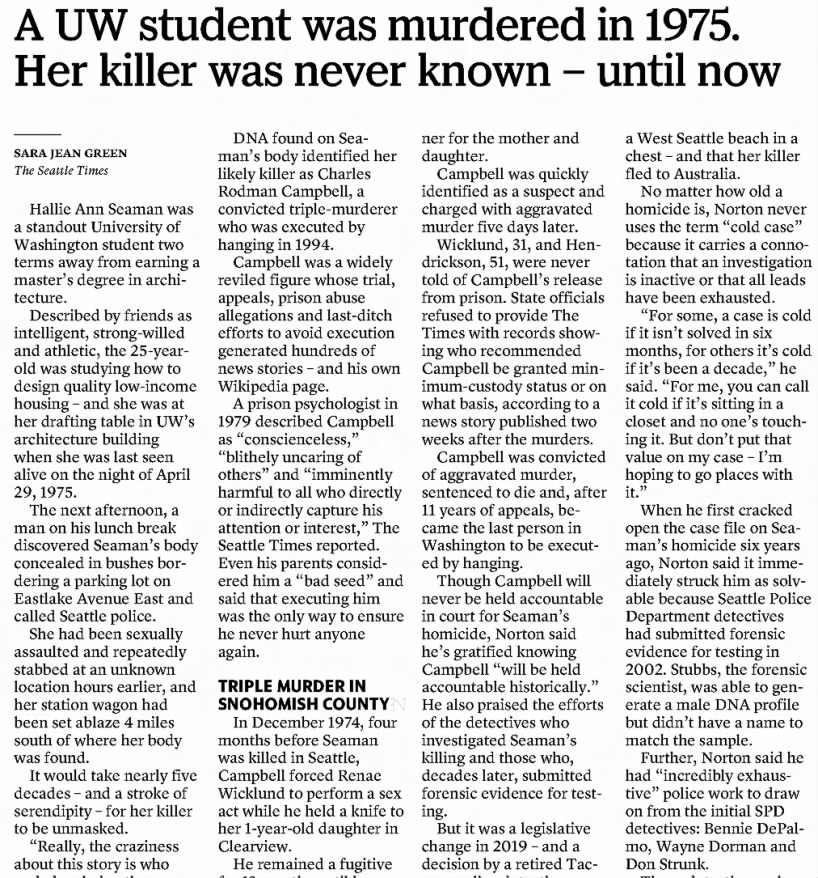

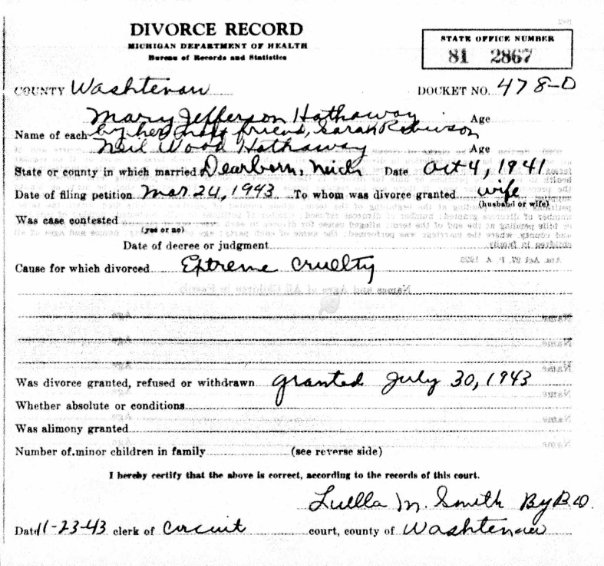

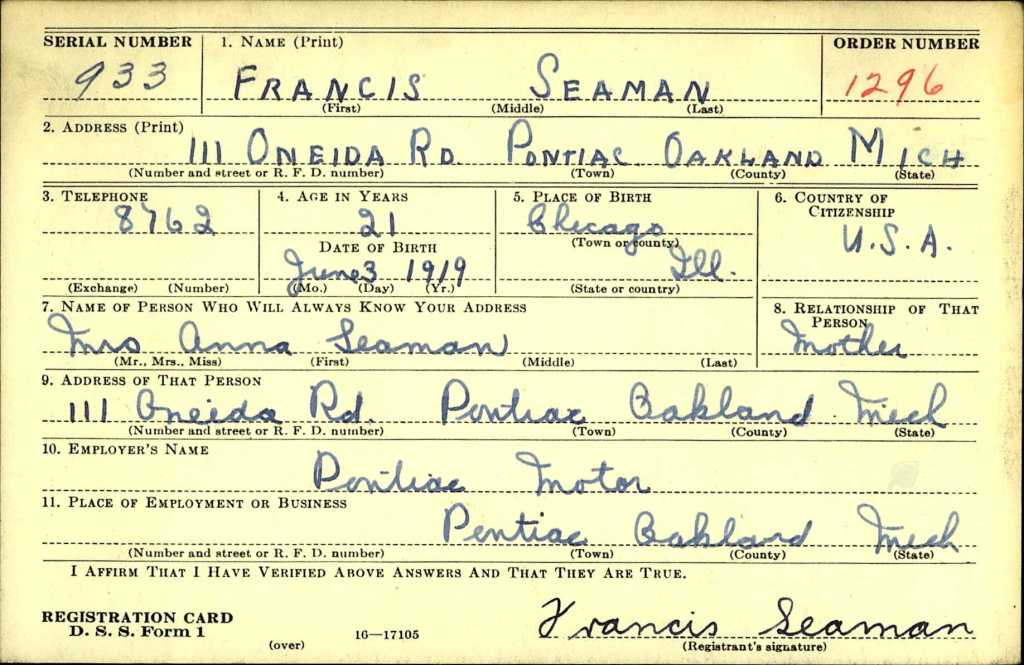

Introduction: Hallie Ann Seaman was born on July 2, 1949 in Michigan to Francis ‘Frank’ and Mary (nee Jefferson) Seaman. Frank was born on June 3, 1919 in Chicago, and after his mother died when he was young, he was adopted by Anna R. Seaman and moved to Pontiac, MI; he changed his surname to Seaman in 1937. Mary Alice Jefferson was born on September 27, 1923 in Ypsilanti, Michigan and was married to a man named Neil Wood Hathaway before she got married to Hallie’s father: the two were married on October 4, 1941 (she was only eighteen!) and divorced not even two years later on July 30, 1943 on the grounds of ‘extreme cruelty.’ Mary Alice graduated from Eastern Michigan University and joined the ‘US Cadet Nurse Corps’ during WWII in October 1944; she got married to Francis Seaman on January 11, 1947 and the couple had three children together: Hallie, Thomas, and Jill (b. 1952).

Francis earned his seaman’s papers and worked on ships in the New York City harbor, and was later employed on the assembly line at the Ford Motor Company. He earned a BS in chemistry, a master’s degree in Sociology, and a PhD in philosophy from the University of Michigan, and in 1949 got a winter teaching position at the University of Idaho; he worked as a lookout on Bald Mountain and pulled lumber on the green chain for Potlatch Forest Inc. (now Potlatch Corporation) during summers. He eventually became the head of UI’s philosophy department, and helped create the school’s general studies program.

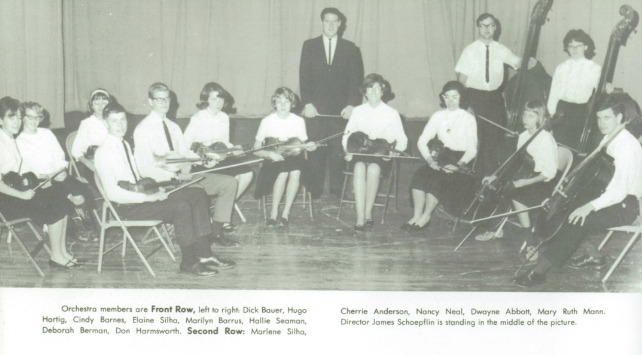

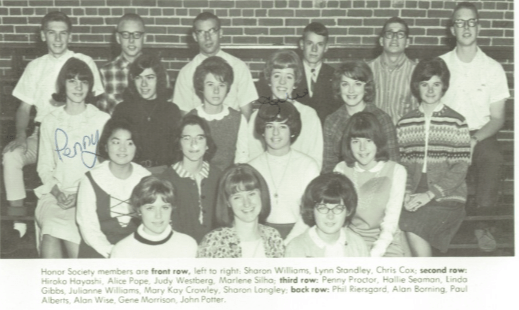

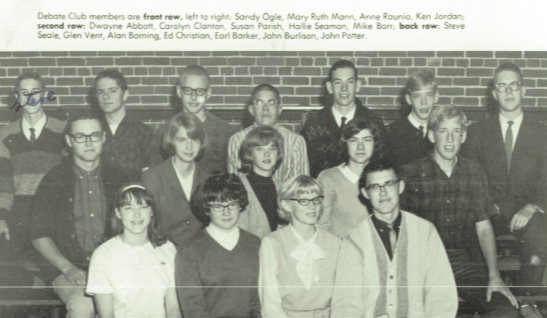

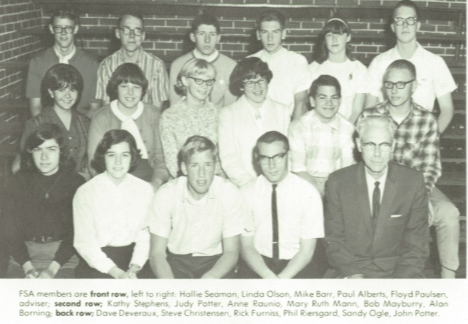

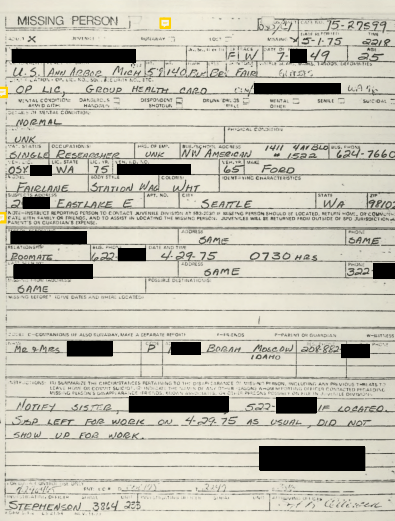

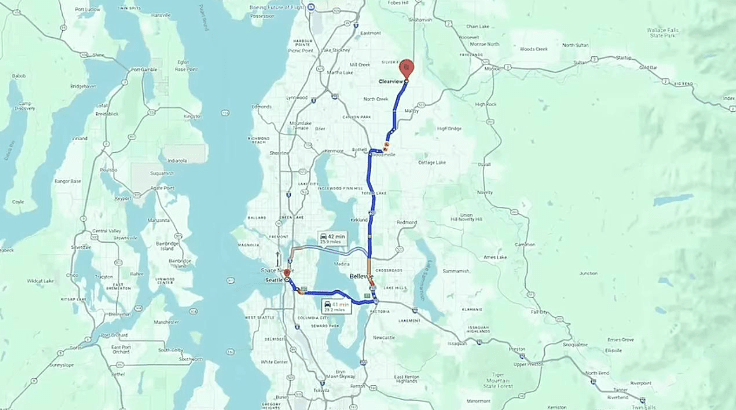

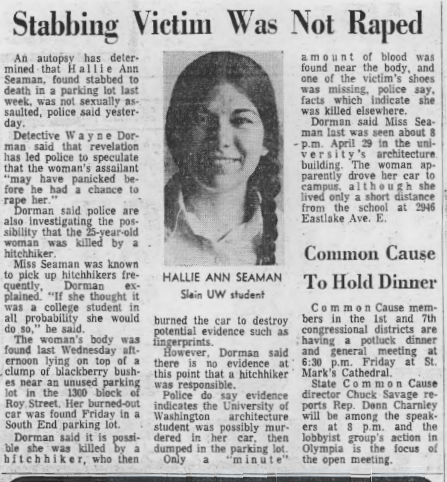

Background: Hallie Ann Seaman attended Moscow High School in Idaho, where she was very active in extra-circular activities: she was inducted into National Honor Society and participated in Orchestra, the Future Scientists of America Club, Drama Club, and Debate Club. After graduating in 1966 she earned her undergraduate degree from Reed College in Portland, Oregon, and after graduating went on to attend the University of Washington. At the time of her death in the spring of 1975 Seaman was twenty-five years old and an honor student, and was only two terms away from earning a master’s degree in architecture; specifically, she was interested in learning how to design high-quality, low-income housing for people in need. Both of the Seaman sisters had relocated to Seattle from Moscow, and were both brilliant students with great scientific minds. Described by those that knew her as an ‘intelligent, strong-willed and athletic,’ Hallie was studying how to design quality low-income housing, and according to her missing person’s report, she had green eyes, stood at 5’9″, and weighed around 148 pounds.

April 29, 1975: According to Hallie’s father, she had recently broken up with her boyfriend (who was a dentist from Pioneer Square), but according to the bf, she was upset with him for working so much and the fact that they didn’t spend a lot of time together. Per the missing person’s report that was filed on May 2, 1975 by Mr. Seaman with the King County Sheriff’s, Hallie left the apartment she shared with a friend located at 2946 Eastlake Avenue East and headed for work, where she was employed as a researcher at a real estate firm. After the murder a fellow architecture student named David Keyes-Nations came forward and told investigators that he saw her on April 29, 1975 sometime between 9:30 and 9:45 PM* talking on the phone while sitting at her drafting table in her studio in the basement of the architecture building; he said that Seaman had been wearing her raincoat and when he walked by again ten minutes later she was gone; her studio showed no sign of a struggle. *A newspaper article lists the time as 8 PM.

To get to her car after leaving her studio, Hallie had to walk down a dimly lit path that was lined by overgrown evergreen shrubs, and all her killer would have had to do was sit and wait. Despite this, Sergeant Mike Mudgett with the University of Washington Campus Police Department doubted that the man that killed her would have done that, because as they exited the parking lot they would have had to pass by a security guard booth.

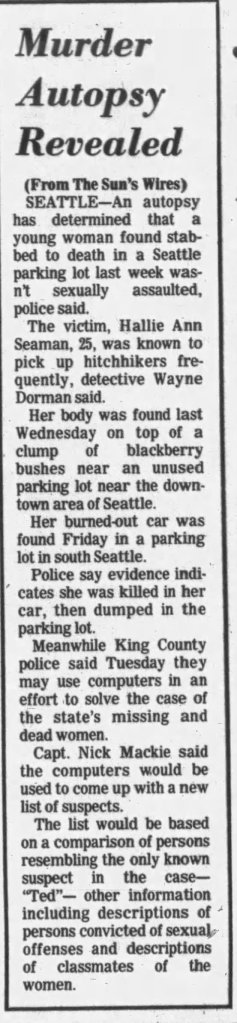

Hallie’s apartment was only 1.7 miles north of the University of Washington campus, and after leaving school that evening she had plans to stop by her boyfriend’s then was supposed to go see her sister, but they both said she never showed up. After she never showed up, Jill went over to her apartment to check it out, and she told investigators that she didn’t think her sister had ever come home that night: ‘she told her boyfriend she was coming over to see me that night. He talked to her at 7:30 and she said she had a class that evening, and then she was coming by my place, but I never heard from her.’ They also went looking for her vehicle in its usual spots (school, work, her apartment) and never found it. Seaman’s boyfriend told investigators that ‘she picked up hitchhikers, but only a certain type: one that was clean cut and looked like an average student. She was independent and confident and not likely to be talked into any type of potentially dangerous situations. There weren’t many situations Hallie couldn’t handle.’ Because of this, police strongly suspected that she may have picked up the wrong person (or people).

On May 1, 1975 at 2 PM investigators received a call from an anonymous woman that was too afraid to give her real name: she told them that roughly forty minutes after Seaman was last seen at approximately 10:30 PM she was driving with a friend in the Lake Union area close to the U of W when they saw two males (the driver had long curly blonde hair and the passenger had shorter dark hair) placing a young woman in the back of a white Chevrolet (that very well could have been Hallie’s car) that appeared to be unconscious (or even dead). The caller said that she didn’t get a good look at the woman’s face, but she did ‘see her underpants,’ and she had on ‘red panties and a light-colored olive coat,’ and she would have been able to ID those. She told police that she was disturbed by what she saw and fear made her flee, but immediately after she had second thoughts and went back, but by the time she had gotten back they were gone.

According to Detective Wayne Dorman, who took the woman’s report, she said: ‘I was driving home when I saw something very, very disturbing. It was near the University at the corner of NE 40th and 8th NE. I saw an older white station wagon. It might have been a Ford—I don’t know cars that well. There were two men in it. The passenger had dark hair and the driver had long, curly blond hair. But before they drove away. I saw the driver outside the car. He was loading this girl into the back seat, and, ah . . . she looked like she was unconscious or maybe even dead.’

When Detective Dorman asked her ‘what makes you think that?’ she replied, ‘well, her legs were spread wide, so wide I could see her panties. They were multicolored and she had on black sandals with two- or three-inch stacked heels. I wanted to stop and try to help her, but the people with me said we could be in danger if we tried to get involved. At least, I talked them into driving around the block to get another look, but by the time we circled back, the white wagon was gone.’ Dorman asked, ‘could you identify the men you saw?,’ to which she replied, ‘I don’t know. Maybe the blond one. They were under the streetlight.’ However, when the detective tried to persuade her to at the very least give him her phone number, the caller hung up.

Investigators were never able to confirm if the woman’s story was true, but they thought the chances were pretty good; according to Detective Norton, ‘whether or not that was Hallie, I don’t know to this day.’

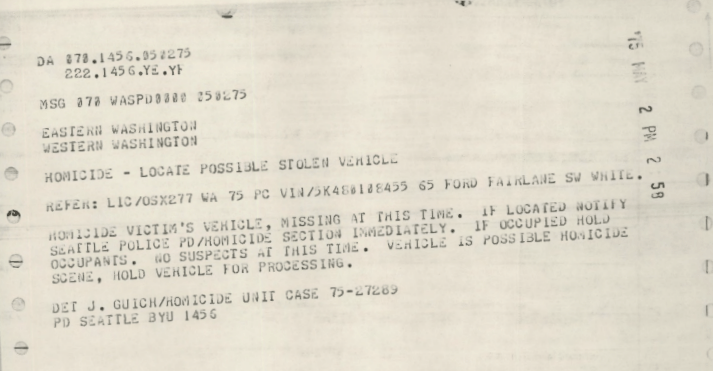

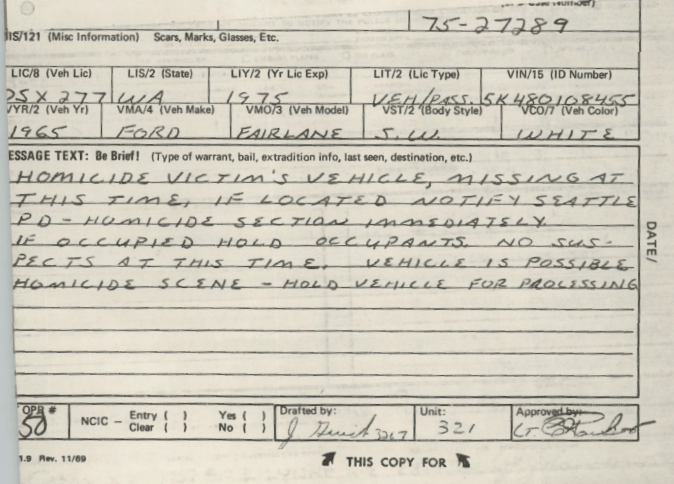

Fire: Around 2:40 AM on May 2, 1975 detectives received a phone call from the Seattle Fire Department in regards to a white 1965 Ford Fairlane 500 station wagon that was on fire in the Sodo neighborhood; it was found in a shipping container storage lot owned by the Sea-Land Corporation that was located only three miles south of where Seaman’s body was recovered, and local investigators didn’t connect the dots between the burnt car and the deceased young woman until after she had been identified; they strongly suspect that Seaman was killed in her vehicle. Even though the Burlington Northern Railroad Line kept a switch engine with a 24-hour crew in the area where Seaman’s car had been recovered, no one had seen who had left there.

Jack Hickam was the responding firefighter from the ‘Marshal 5’ fire district that processed Hallie’s car, and he determined that the fire didn’t start in the engine but rather in one of the seat cushions; he also got a ‘probable’ reading for flammable liquid when he used a hydrocarbon indicator. Despite criminalist Ann Beaman from the Western Washington State Crime Lab literally sifting through the vehicle’s ashes, no helpful evidence was recovered from Hallie’s car, but she was able to find her missing shoe, which had part of a nylon melted into it along with a charred coin purse and part of a key chain. The driver’s side door handle (which was thrown clear from the scene when the gas tank exploded) was also tested for fingerprints but nothing useful was found.

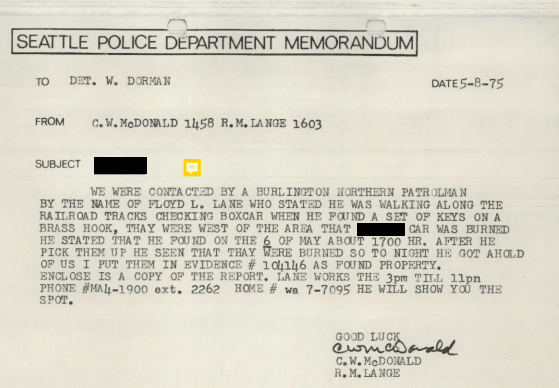

Keys: In a Seattle Police memo dated May 8, 1975, a patrolman in Burlington named Floyd L. Lane was walking along some railroad tracks two days prior checking out boxcars when he came across ‘a set of keys on a brass hook.’ He was west of where Seaman’s car was found and after he examined them he realized they were partially scorched and decided to reach out to the detectives investigating the burnt Ford.

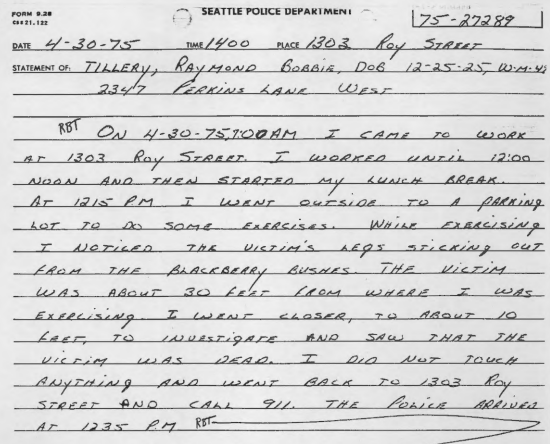

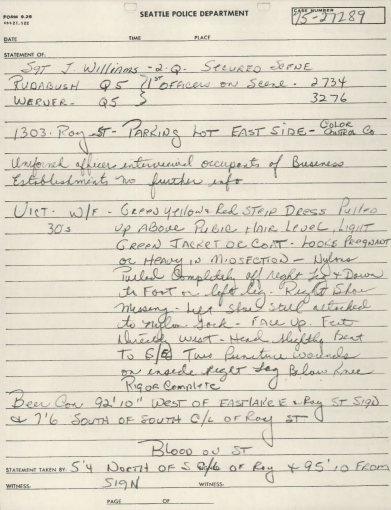

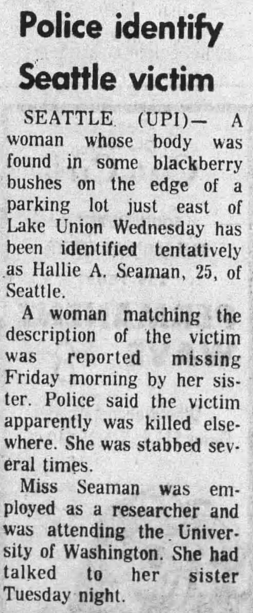

Discovery: Only fourteen hours after she was last seen alive at roughly 12:15 PM on April 30, 1975 Seaman’s remains were found in South Lake Union only a couple of miles south of her apartment by a man named Raymond Bobbie Tillery. Tillery was on his lunch break exercising in a parking lot near his POE when he discovered her body: it had been hidden by an overgrown thicket of blackberry bushes beneath the I-5 freeway in front of 1303 Roy Street. He immediately called 911.

Mr. Tillery told police that he first noticed the victims legs from about thirty feet away, and when he got closer, he realized what he was looking at and ran back to his office to call 911. Detectives strongly speculated that Seaman’s body was transported to the scene from another unknown location and was left in the bushes. Dr. Besant Mathews, from the KCME’s office examined the body at the scene, and it was in his professional opinion that the victim was brought there sometime during the early morning hours of April 30, 1975.

In the days immediately following Seaman’s disappearance, a University of Washington professor from the School of Architecture called the King County Sheriff’s and shared with them some concerns about his missing graduate student: ‘she hasn’t been to class for two days, and her description would be pretty close to the ‘Jane Doe’ in the papers and on television. Her name is Hallie Ann Seaman. She’s 25 years old.’ As it turned out, his hint was legit, and on May 2, 1975 Hallie’s sister and her boyfriend went to the King County Morgue and identified her body.

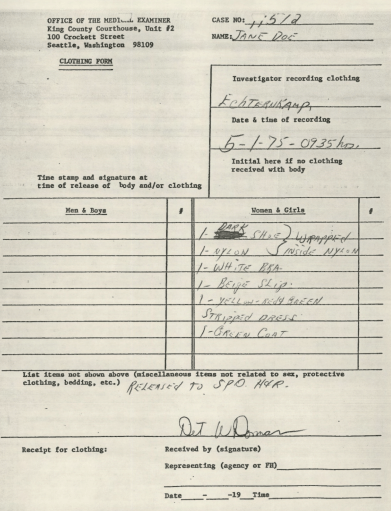

Seaman had been dressed in a grey, yellow, a pink striped dress and a light-colored olive coat (some reports said it was tan), and was not wearing any panties. She had been found lying face up and the nylon on her left leg was found down by her ankle and her left shoe was off of her foot and was tangled up in the stocking; there was no nylon or shoe on her right foot. Responding officers found three cuts in her coat as well as a small amount of blood on the upper part of her left foot. Also found on the scene were pieces of green glass, an empty Rainer beer bottle, a Michelob can, two broken beer bottles (that were all tested for prints), and a blue towel.

The young woman had no purse or ID on her and she wore no jewelry, and investigators presume she had been dead for roughly ‘a dozen hours’ when her remains were found and by then rigor mortis had frozen her body completely. Based on the way she was discovered, the victim most likely had been laying face down somewhere for a few hours after her death before she was eventually repositioned and left on her back, as she was found. It was clear to the detectives that she had been left in the parking lot but had been killed someplace else, and she had been found immaculately clean, right down to her unpolished fingernails and had worn little to no makeup.

Autopsy: She had obviously put up quite a fight, as her arms bore a great number of defense wounds. The King County medical examiner, Dr. Patrick Besant-Matthews said that she had been stabbed eleven times (one report said it was twelve) and had wounds in her liver, stomach, lungs, and aorta. The knife that the killer had used was between two and a half to three inches long and detectives said he must have been in a frenzy because it was the kind of violence only seen after an attack by a sexual sadist, or someone that deeply hated his victim.

During her autopsy the ME located two stab wounds located on the left side of her abdomen, and determined she was somewhere between five to six months pregnant. Detectives found no blood underneath or around her body aside than a few droplets on some leaves that were found below her; she had two cuts approximately 1.5 inches long on the lower part of her right leg and had numerous bruises on both of her legs.

Hallie’s fatal wounds were located on her right side, when the killer’s blade pierced her kidney and severed her aorta. Even though the documents released to me from King County said that it was determined by the ME she had not been sexually assaulted, other sources say she was (I’m more likely to go with the Sheriff’s Department over a podcaster, no shade to them). King County Detective Wayne Dorman said that this fact surprised him and it made investigators wonder if Seaman’s assailant ‘may have panicked before he had a chance to rape her.’ He also said they wondered if perhaps she was killed by a hitchhiker she picked up that perhaps she ‘was a college student. In all probability she would do so.’

The ME working the case took twelve polaroid photos, six of which were left behind at the King County Medical Examiners office; the victims fingerprints were taken to the FBI, but she didn’t come up in any police databases (as she had no criminal record). Clothing and articles that were found with the body were examined and put in the property room at the King County Sheriff’s department: her green coat and dress had no labels and appeared to have been handmade and the nylons that was found with her shoe appeared to have been part of some panty hose that were cut at the top by something incredibly sharp, possibly a knife or a razor; the other leg that had the attached ‘panty section’ of the hosiery had been pulled down over her left leg and was found inside out so that her stacked-heel black sandal was caught inside.

On 5:50 PM on April 30, 1975 King County 911 Operator #75 received a call from an anonymous caller that stated a man (whose name was completely blacked out in the police file) had killed the victim, and it was then that a second operator came on the line and said that the call came from a redacted address, that was actually Farwest Service Corporation, or Farwest Taxi (they blacked out the address but not the name of the business?). Investigators checked into the suspect in the ‘R/B information’ (which may or may not stand for ‘running book’), and discovered he worked as a cook, had blond hair, and weighed 210 pounds; he also had a history of assault, robbery, and auto theft along with multiple arrests and convictions on his record. He was eventually cleared.

On May 6, 1975 Hallie’s boyfriend reached out to investigators (he was also from Idaho and was home visiting) and told them he was upset over the story that was printed about her in the newspapers, to which they said they have ‘no control over the press.’ From there, the detective told him that the polygraph exam he agreed to was scheduled for Friday, May 9, 1975 at 1:30 PM and that he should arrive fifteen minutes beforehand. During the interview with detectives, he said that his girlfriend typically wore white underwear and at the time she was killed the wallet that she was using was a man’s, and there was no metal on it except the snap on the leather band to help keep it closed. Seaman’s boyfriend said that the last time he had intercourse with her on Saturday, April 26th and she did wear nylons most of the time but didn’t cut them at the top in the way that the victims was found.

Ted Bundy: At the time of Hallie’s murder in the spring of 1975 Ted Bundy was still out and about living the good life, and wasn’t arrested until later that August. He was still living in his first Utah apartment on First Avenue in SLC and was attending law school at the University of Utah; he was also towards the end of his multi-year, long-distance romance with Elizabeth Kloepfer (who he was not even remotely faithful to, as he was dating multiple other women). However, one thing jumped out at me about Hallie possibly being a Bundy victim: the last time he was active in Washington was July 1974: although not completely unheard of, that’s quite a bit of time in between victims.

I can see why Hallie would initially be thought to possibly be a Bundy victim, as she (very obviously) fit very neatly into his typical victim type: she was an academic, and was slim, young, and beautiful, with thick, beautiful chestnut hair that she wore (VERY) long and braided down her back. She was also by herself and in a public place, and just the year prior he had abducted two other students on the University of Washington’s campus: Lynda Ann Healy and Georgann Hawkins (and attacked Karen Sparks).

Hallie’s Killer: In 2002 detectives submitted forensic evidence that had been collected and preserved from Seaman’s autopsy in 1975 to the Washington state crime lab, who in turn generated a DNA profile of the suspected killer; sadly there were no hits in CODIS (the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System that was created in 1998 to share genetic profiles of certain felons in all fifty states). The case was reopened in 2017 and in an attempt to find new leads, Seattle police Detective Rolf Norton tried to utilize the field of genetic genealogy, which tested unknown DNA samples taken from crime scenes and tested it against publicly available genetic profiles in an attempt to identify possible suspects (like Ancestry or 23andme.com). Unfortunately for the detective, the lab had utilized the entire genetic sample when generating the suspected killer’s genetic profile in 2002 (which sometimes happens), so that wasn’t possible. In 2019, lawmakers in Washington passed new legislation as a continuation of their 2015 Sexual Assault Kit Initiative, which made all state policing agencies to submit all untested rape kits to the crime lab for testing, thus expanding the criteria for whose DNA could be included in CODIS.

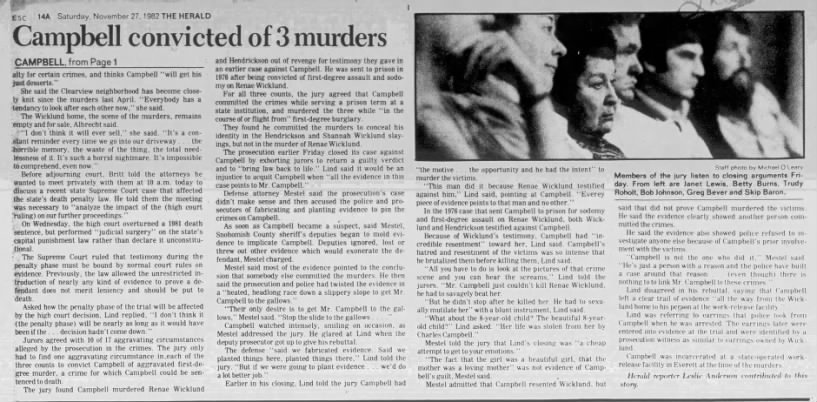

In 2023, DNA tests posthumously linked a Washington killer named Charles Rodman Campbell to the murder of Hallie Ann Seaman. In a 2023 article with The Seattle Times, Detective Norton said: ‘really, the craziness about this story is who ended up being the suspect:’ In August of 2023, he received an email from William Stubbs, a forensic scientist at the Washington State Patrol Crime Lab about the case, who told him a lab report would soon be on its way: ‘he’s like, ‘well, I think it’s going to surprise you, what the result is,’ and I’m like, ‘Pfft. OK, surprise me. And so he sent me a copy of the reports … and I was blown away.’ In the initial stages of the investigation, detectives painstakingly logged over 120 names of possible suspects that came up during the investigation, and Campbell wasn’t one of them.

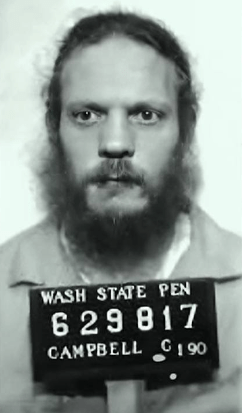

Shortly after his birth in Hawaii on October 21, 1954 Campbell’s family relocated to Washington, and according to his parents he was an angry child that loved to bully other children and when he was twelve his behavioral problems began to escalate: he began drinking and smoking, and at thirteen began using amphetamines. The following year used heroin for the first time and when he was fifteen he had several run-ins with police: he stole a car, and he along with a friend were caught pushing over headstones in a cemetery. In October 1969 at the age of sixteen he was caught breaking into an elementary school, and in 1971 after his father had him arrested for stealing the family car he called a friend on three separate occasions and asked him to shoot his dad; later that July, he was sentenced to a year in jail for burglarizing a house.

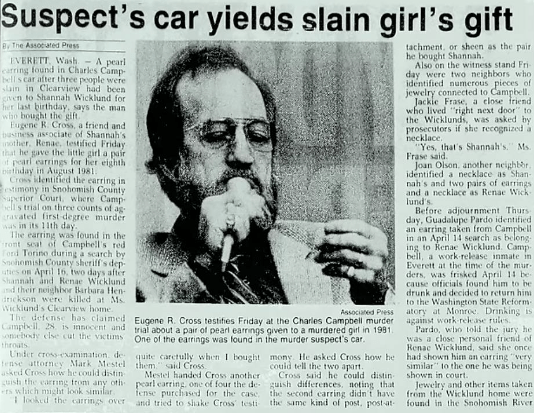

On December 11, 1974 Campbell forced 23-year-old Renae Wicklund to perform oral sex on while he held a knife to her eight-month-old daughter Shanana** then threatened her life and her baby. The young mother was outside washing the windows of her home while Shanana was playing on the lawn when suddenly she noticed a young man running towards her: instincts kicked in and she immediately grabbed her daughter and ran into the house, but the intruder still managed to force his way inside. After the assault Wicklund’s neighbor and friend Barbara Hendrickson came over, and upon realizing what happened called the police. ** I’ve seen her name spelled Shannah and Shannon.

After the violent assault Campbell remained a fugitive for thirteen months until he was arrested on a burglary charge in Okanogan County; he was then brought back to Snohomish County, and after Wicklund picked him out of a police line-up he was charged with first-degree assault and sodomy. The young mother, along with Hendrickson, testified against Campbell at his trial and he was given a maximum sentence of thirty years in prison; unfortunately, he was granted ‘work release’ only six years into his bid on May 1, 1981 (one report said it was seven), which allowed him to leave prison grounds and go out into the community and get a job. Renae tried her best to move on with life after the assault but struggled: she ended up divorcing her husband in 1978, and shortly after he died in a car accident.

While incarcerated, Campbell had a hard time conforming to prison life and staying in line: while there he got into several physical altercations with other inmates, and earned the nickname ‘one punch’ because that’s all it took him to win a fight. He also raped at least two of his cellmates, one of which was a childhood friend and according to the CO’s he was also dealing drugs.

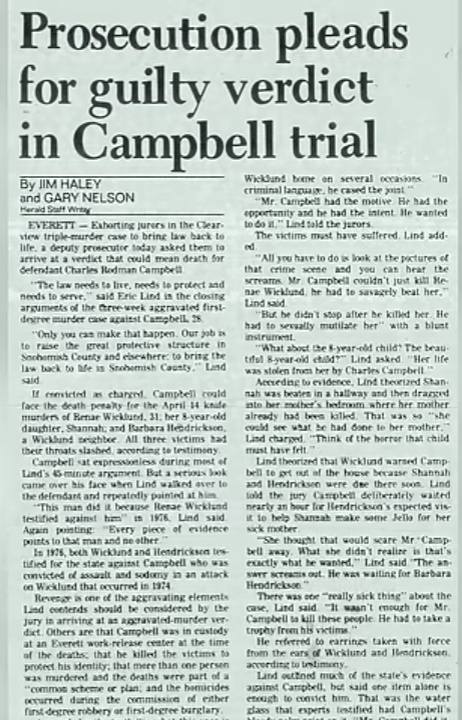

While on work release, Campbell was allowed to leave the facility during the day but had to return in the evening, and Wicklund lived about fifty miles away from the facility (she never moved out of the home she was assaulted in). In the spring of 1982 the 31-year old was working for a local Beauty School, and after staying home sick on April 14th Campbell returned to Renae’s residence and cut her throat: she was found naked on the floor of her bedroom and had been strangled and severely beaten with a blunt object.

When her (then) eight-year-old daughter arrived home from school later that same afternoon he ambushed her and brought her into the room where her mother’s dead body was; he then strangled her and slid her throat nearly to the point of decapitation. Almost immediately after he killed Renae and Shanana, 51-year-old Barbara stopped over to make her sick friend some Jell-O as a snack; he took her life as well. It’s strongly speculated that Campbell’s motive for returning to Wicklund’s home to further victimize her was revenge due to her and Hendrickson having testified against him during his trial for Wicklund’s rape.

While Campbell was out on work release he got his girlfriend pregnant and his son Jacob was born on October 18th, 1982. During his November 1982 trial the prosecution presented a great deal of evidence against him, including the fact that one of Shanana’s earrings were found in his car, his fingerprints were found on a glass at the crime scene, and another neighbor saw him leaving Wicklund’s home the day of the murders. The trial lasted fifteen days and the jury only needed four hours to find him guilty of all three murder counts and recommended he be sentenced to death; the judge agreed with this decision and on December 17, 1982 he sentenced Campbell to death.

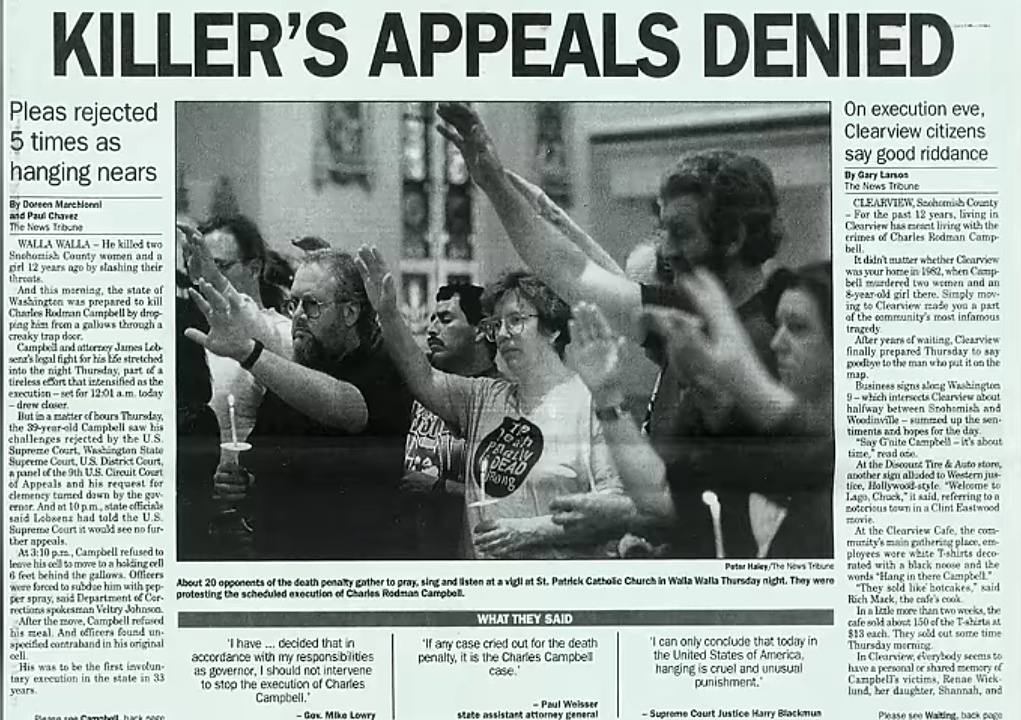

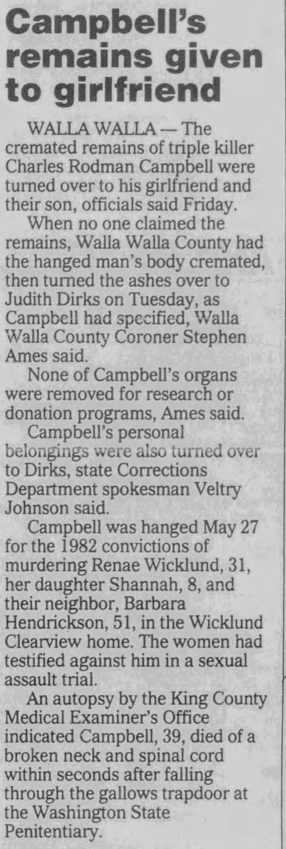

Campbell fought his death sentence to the very end and filed appeal after appeal with no success, and after twelve years of sitting on death row at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla he was put to death on May 27, 1994. The day before his execution he was due to be moved to a different cell that was closer to the gallows, but he refused to cooperate with correction officers and laid down on the floor; in turn, they used pepper spray to get him to comply. Campbell’s last meal consisted of fish sticks, a tossed green salad, scalloped potatoes, and a cherry tart; he didn’t eat a single bite.

When it came time for his execution to be carried out Campbell also refused to walk to the gallows, and he needed to be strapped to a board and carried to the trap door; while on it, he kept moving his head which prevented prison staff from putting the hood and noose on him. He didn’t have any final words, and at 12:12 AM he dropped through the trap door and was pronounced dead two minutes later. He was the last death row inmate to be executed by hanging.

Noting Campbells’ notoriety, a (now retired) Tacoma Detective that was working for the state Attorney General’s Office named Lindsey Wade decided to submit Campbell’s DNA profile into CODIS (despite his crimes in Snohomish County predating the creation of the database). Then came the news that DNA had connected him to the murder of Hallie Seaman, and according to Detective Norton: ‘serendipity came together with some great investigative work from ’75 and Lindsey Wade thinking out of the box and making some really, really great decisions.’

Upon the realization that Campbell was out of jail for a little over a year between his attack on Wicklund in 1974 and his capture in early 1976, Detective Norton encouraged other Washington police jurisdictions to look at their own unsolved cases from that time frame to see if it’s possible he committed additional homicides. Additionally, after his conviction laws in the state were changed so that victims of violent crimes and people that testify against offenders need to be notified upon their release.

After Hallie’s murder was solved Detective Norton said that he had been in touch with her sister and brother but declined to discuss their conversation as they requested privacy. When asked if solving an almost fifty-year-old homicide can bring closure to a family, he said it’s tough to say: ‘is it harder now, that the bandage gets ripped open again after all these years? I don’t know. You’re cognizant of that when you’re reaching out to families and having these discussions. My guess is that most would like to know, rather than not knowing. However, you’re bringing up the worst thing that ever happened to a family and laying it on the table again.’

Dr. Jill Seaman MD: Hallie’s sister has led quite an impressive life: after graduating from Moscow High School in 1970 she relocated to Vermont where she attended Middleburg College and got a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1974; from there she returned to the Pacific Northwest and in 1979 earned her MD from the University of Washington Medical School. She is a board-certified family practice Doctor and in 1988 advanced her education even further and attended the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

After graduating from medical school, Dr. Seaman moved to Alaska, where she worked as the Chief Medical Officer at a 50-bed hospital in Bethel treating Yupik Native American Indians. In 1984, she went to Sudan, where she served as a physician for the International Refugee Committee in a makeshift hospital and the following year she worked at a therapeutic feeding center catering to Ethiopian refugees.

While in the South Sudan between 1989 and 1997, Dr. Seaman battled an epidemic of kala-azar (or visceral leishmaniasis), and in 2000 her and a colleague developed a successful program in Lanken (a village east of the Nile River) against tuberculosis. In 2009 she was named a MacArthur Fellow (or a ‘genius grant’) winner and has written and co-authored numerous articles that were published in various medical journals. In 1997 she was featured in Time Magazine’s special on ‘Heroes of Medicine’ and has won numerous awards for medical and humanitarian services. In recent years Dr. Seaman splits her time between Africa and Alaska, where she provides public-health services to Yup’ik Eskimos. She also has her own Wikipedia page and is married to another MacArthur Fellow winner.

Jacob Campbell: According to his website, Charles Campbell’s son was raised knowing what he did and some of his earliest memories include sitting in a courtroom in Snohomish County with his father. Despite not knowing his dad outside of a prison environment, Jacob claimed the two had a good relationship, which he credits to weekly visits with his mother along with frequent letters. In 1994, when Jacob was in sixth grade he petitioned the Governor of Washington state in an attempt to save his father’s life, but was unsuccessful.

After the death of his father Jacobs’ life began to spiral out of control: when he started High School he got deeply involved with the party scene and began to drink heavily and abuse any substance he could get his hands on. While spending some time in the Benton County Correctional Facility as a juvenile he learned about a program called Jubilee that helped him turn his life around, and now he is a husband, father, and a Doctoral Student in Transformative Studies (PhD) at the California Institute of Integral Studies.

Conclusion: In the days that immediately followed her murder a friend of Hallie’s recalled what a great loss her death was to so many people: ‘she was a bright, dynamic girl. She was the most dynamic creature I’ve ever seen. Suggest something and it would be done. She had tremendous drive.’ One of her professors said that she ‘was one of the most brilliant students we’ve had. We’ll never know how much she could have done to help low-income families have decent housing.’

Mr. Seaman was born with a circulatory brain malformation, and after a run in 1991 it burst and left him unable to walk or talk. With his wife’s encouragement, he learned to walk again, and according to his obituary, he enjoyed running, gardening, and always maintained a positive attitude and sense of humor. In 1964 he was named the University of Idaho’s outstanding faculty member and worked with Moscow schools helping with the moral development of children, and even served on the school board during the 1980’s and 1990’s. He was also a charter member of the Unitarian Universalist Church of the Palouse, a member Phi Beta Kappa, and was a founding member of the Outer Circle (a multidisciplinary university discussion group). He died at home at the age of seventy-nine on September 6, 1998. Hallie’s mother Mary died at the age of seventy-five on November 5, 1998 in Moscow, Idaho.

According to her obituary, Mrs. Seaman was the youngest of eight children and attended the State Normal School in Ypsilanti and later studied nursing at Cook County Hospital at Chicago. During World War II, she learned drafting for the Willow Run Bomber Plant in Michigan and when she was done serving her country continued her education at the University of Idaho in Moscow. During her working years she held several different jobs, with positions ranging from assembly work to dress designing until she became a mother and left the workforce so she could devote all of her time and energy into raising her three children. Mrs. Seaman was involved in Moscow city planning in an attempt to help save its downtown, however after Hallie’s murder she retreated from outside activities and concentrated on writing, architecture, and landscaping (especially her own home and garden). She was a member of the University Arboretum Associates and the League of Women Voters as well as multiple women’s rights groups and literary and environmental organizations. After her husband’s cerebral hemorrhage in 1990, she dedicated all her time and energy to his care. Tom Seaman still resides in Moscow, and according to his father’s obituary he was an ‘avid traveler.’ At the time of her father’s death Jill was practicing medicine in Nairobi.

Works Cited:

Banner, Patti (May 13, 2024). ‘DNA Links Killer to University of Washington Student’s Death.’

Green, Sara (Jean December 23. 2023). ‘A UW student was murdered in 1975. Her killer was never known, until now.

jacobrcampbell.com/testimony/

LA Times (no author listed). ‘Killer Struggles with Guards Before Hanging.’ (May 28, 1994).

Rule, Ann (December 2004). ‘Kiss Me, Kill Me: Ann Rule’s Crime Files Volume 9.’

lmtribune.com/northwest/frank-seaman-79-retired-ui-professor-75773

A copy of the notes from a meeting about Bundy that took place on November 13 and 14, 1975 at the Aspen Holiday Inn. The document begins with a letter from Lieutenant William H. Baldridge of the Pitkin County Sheriff’s Department, and was organized by Pitkin County deputy Mary Wiggins.

Courtesy of the King County Sheriff’s Department.

Tape three was completely removed by KCSO as unplayable in September 2000.

Bundy Tape 11, circa 1974: Detective Roger Dunn, follow-up, case 75-54324. Removed by KCSO as unplayable, September 2000.

Bundy Tape 15A, circa 1975: Statement of Jerry Snyder, case 74-123376. Removed by KCSO as unplayable, September 2000.

Tape 17, both sides unplayable.

Bundy Tape 18, circa 1984: Consultation on Green River Murder Case, removed by KCSO as unplayable, September 2000.

Due to the sheer mass of information I am dividing these documents into two separate articles.